Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowNevilles' Advocate

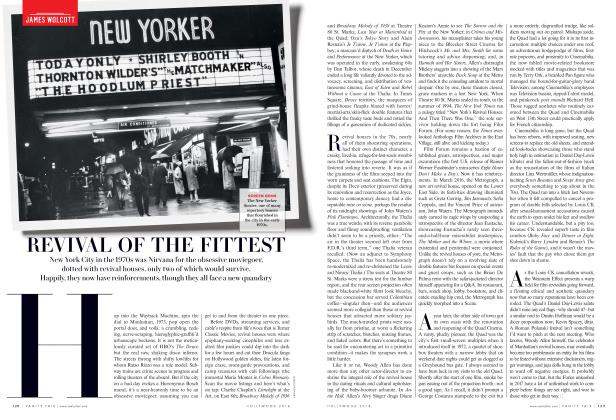

LEON WIESELTIER raves for the Neville Brothers

There are those who rush to meet the world and those who await the world. The Neville Brothers have been awaiting it, in New Orleans; and it is finally coming to them. Art and Aaron and Charles and Cyril Neville are the best band in America. Aaron Neville is certainly the best singer in America. He can sing almost anything. He does not have a voice; he has voices. Sometimes they seem to sound uncannily together, the pretty falsetto and the dirty tenor singing almost in unison.

Pressed against the stage of a New Orleans club, beneath the big black amplifiers turning the Nevilles' euphony into thunder, I reflected recently that the jumping justesse of their music, its extraordinary rightness every time it's played, owes much to the fact that they have made it where they are at home. These days they are New Orleans's favorite sons. Their music is a perfect reflection of the almost demented density of the city's culture. French, Spanish, English, Canadian, Caribbean, African, American: New Orleans was the first melting pot of culture in the New World. There is no other American city, moreover, that can match New Orleans for the variety of its black traditions, partly because of its location in the middle of Latin, Caribbean, and American black civilization, partly because Jim Crow didn't really hit New Orleans until late in the nineteenth century. Thus, when the Nevilles play funk or reggae or soul or rock 'n' roll or blues or jazz, or all

of them together, they are perfectly in the spirit of their place.

The contemporary revival of interest in the Neville Brothers, and in Allen Toussaint (who wrote some of his first great songs under the name Naomi Neville), and in the sixties and seventies music of New Orleans generally, corrects a great injustice of American popular taste. During those decades New Orleans was eclipsed by Memphis, where Stax and Atlantic recorded Booker T & the MG's and others, by Muscle Shoals, which drew white musicians eager to borrow a bit of authenticity, and by Detroit, whose Motown provided the most universally acceptable black music of all. The music of New Orleans, by contrast, always had an edge to it, a gesture at the grotesque, a reminder of rawness. It was angularly adult, even when it was produced by teenagers. (The Nevilles were in high school when they formed their first bands.) The innocence of New Orleans, unlike the innocence of Motown, was always accompanied by an echo of experience. Its perfect emblem is the pale tattoo on Aaron's left cheek; it jolts you into the thought that maybe the singer has a story that is not covered by the sweetness of his song.

Aaron's first record was released in 1960. It was called "Over You," and was a rather undistinguished rock tune composed to a poem that he wrote in prison, where he sat for six months as a result of what one critic calls "some unspecified, adolescent misdemeanor." The record is a decent occasion for

dancing, until you pay attention to the words. Then you realize that you are dancing to a very catchy threat of murder. The song begins with Chopin's funeral theme execrably banged out on an angry piano. Then the horns introduce a nineteen-year-old soulfully singing this:

There'll be some slow walking There'll be some sad talking There'll be some flower bringing Gonna be some sad singing Over you I say over you

Over you, pretty baby, if I ever hear you say we're through.

The song proceeds, with startling satisfaction, to imagine the funeral of the singer's truelove: "There'll be a hole about six feet deep / For you baby to take your sleep / Into a pine box down you'll go / Where you'll stay in sleet or snow." Now, this is rather more than what the rest of the country meant by teen anguish. Indeed, it is the counterpart in soul music of the fantasies of violence that made the rural southern blues of Robert Johnson so frightening—except that Aaron's bloodthirsty little ditty made the charts.

Even the teen soul of New Orleans, then, reminds you that it is America's jolly capital of morbidity, madness, and death. This is a city that named its airport after a pilot who crashed, that named its old business center after a businessman who went bankrupt. Each of its quarters seems to be designed for a different style of decomposition. The Gothic opulence and turgid privacy of the Garden District offer a better quality of derangement than, say, the shadeless streets that carry the streetcar named Desire and therefore the traces of Stanley and Stella's undoing. The town is lousy with invitations to lose your inner bearings, with socially sanctioned rituals of temporary release. There are the masques of Mardi Gras for those who like to take their own unhinging with art; and voodoo for those who like to take it with religion. In New Orleans you can still buy funeral insurance. Funerals, in fact, were a formative ritual for New Orleans's music. The angel of death liked to work in four-four time. It was from the marching bands of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries that the city derived its peerless way with brass and horns; the piano came later, and the guitar, which always reminded the southern city of the southern country, never quite made it.

But anybody who has read the Creole poets of the last century, or Tennessee Williams, or Walker Percy, knows that in New Orleans the feeling for decay comes with a feeling for loveliness. I know of no other American city that stands so proudly for the great Roman* tic principle that melancholy is beautiful. You will find some of the tawdriest tenements in New Orleans on streets named for the Muses. (Hard to imagine a curb called Melpomene in Manhattan.) Out of its history and its humidity and its hallucinations the city has distilled a really perdurable lyricism. And it is in the grand tradition of New Orleans lyricism that the Neville Brothers belong.

Especially Aaron; he can make you soar with a song like "Wildflowers" (I swear). Aaron singing is the image of the artist in full possession of his powers, and knowing it. Physically he is impossible to forget; he looks like a mixture of steel and silk. But it is the expression on his face, or rather the absence of any expression on his face, that reveals his extraordinary authority. Onstage Aaron is supremely impassive. He shows nothing, until he sings. Then the power of his figure recedes before the indescribable delicacy of his tone. Even then his face will tell you nothing. His voice, however, will tell you all.

Aaron possesses an abundance of what is usually called "range," except that Aaron's range is more than musical. Like Rameau's nephew, his virtuosity is finally of knowledge, of the heart; he sings all the parts because he feels all the feelings. He seems to take a special pleasure in recording the sorriest and silliest standards of the 1950s and 1960s, as if to prove that there is beauty in banality, banality being only a haughty name for how most people live. He can make "For Your Precious Love" sound like Doretta's song. A few months ago he released a record of rock 'n' roll ballads called Orchid in the Storm (Passport Records). In American popular music you have to go back to Sam Cooke for something this gorgeous. "Earth Angel" never had it so pure. But an earth angel is precisely what Aaron sounds like. □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now