Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowCROSSOVER NIGHTMARES

Plácido Domingo tackling "Moohn Reevehr"? Ronstadt flattening Sinatra? Give us a break

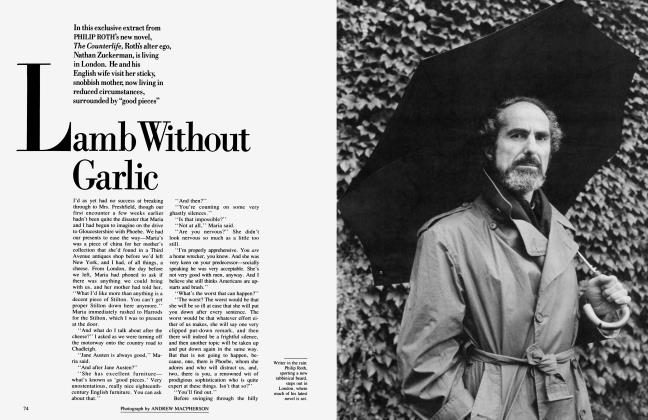

LEON WIESEUIER

Mind's Eye an there be a more magical word in music than crossWover? Singers and musidans have been crossing over as if their lives depended on it. "I know it's hard. . .to leave the things you know behind," says Ruben Blades in Crossover Dreams. "But if we stay... we're dead." From where he stands, on a bald tar roof in the barrio before bald tar roofs as far as the eye can see, crossing over, under, or around the unrelieved urban bleakness might indeed seem like survival. But most of the crossover kings and queens of our day are not trapped in a spirit-smashing life. They are not angry about the awfulness of their origins. They are, rather, embarrassed by the specificity of their origins.

After all, everybody comes from only one place; and so does everybody's music. In art, though, narrowness is usually a strength. It forces you to go deep, not wide. It trains your sights upon problems for so long and so hard that a personal style may be bom. But now comes this crossover craze. Its first mistake, as Blades discovered a little tritely in his film, is overrating the outside world. But there's worse.

A few years ago Pauline Kael had a question for Woody Allen; she demanded to know why on earth a man who could make so many people laugh so brilliantly insisted on playing Hamlet. Her excellent question should now be put to the music business, whose new slogan for success is: Mix water with your wine. Leave what you do well and take up what you do badly. The case of Ruben Blades is hardly the most disheartening. Consider Placido Domingo. Hear (and watch) him in Otello, and then hear him on My Life for a Song, or Perhaps Love. Those records hit a new high in musical risibility. When he sings "Moohn Reevehr," he makes Andy Williams sound like Placido Domingo. When he sings "Ay Dun Tok too Straynjehrs," he makes everybody in the whole world sound like Placido Domingo. This is because, on these extravagantly arranged collections of kitsch, Placido Domingo no longer sounds like Placido Domingo. He sounds like a man with an abject need to be universally loved. His crooning insults all the good people who thought that he can sing anything, by proving that he will sing anything. As he sings his duet with Katia Ricciarelli in Otello, it is a little hard to forget his duet with John Denver on Perhaps Love, and some of Verdi's most limpid passages notwithstanding, the gooseflesh goes down. Why is the greatest tenor of his time (and quite a number of his colleagues, male and female) behaving like Mario Lanza?

Or consider Linda Ronstadt's experience with the dybbuk of Frank Sinatra. Ronstadt has just released the last of her three records of Sinatra-type standards, all of them issued together in a box made to look like the real thing. As an act of homage, particularly to Sinatra's great Capitol ballads of the fifties, the selections are well judged. But like much crossover music, Ronstadt's Sinatra is finally an act of piety, of mimicry. And even the little ditties among the songs fail to disguise the cruel limitations of her voice, its Star Search quality. Compare her "I've Got a Crush on You" with Sinatra's. The wit is gone. ("Could you coo," which is slid across in a perfect mixture of desire and irony in his version, sounds like "coochicoo" in hers.) Or, more substantively, "Guess I'll

Hang My Tears Out to Dry," from Sinatra's Only the Lonely, one of American music's masterpieces. Ronstadt's idea of turning up the feeling is turning up the volume. "When you open it to speak, are you SM AAA AAA AAA A ART?" she screams in "My Funny Valentine," answering her own question. The song has always been a trial of delicacy. Or consider, finally, the case of Miles Davis, and his electric music of the most unelectric kind. His recent records have been triumphs of recording technology, and little more. His most recent, Tutu, is a tight and amiable affair that would have brought a little glory to Weather Report. But Davis's horn hasn't sounded bigger or better or more beautiful in years, and its every manful note stands as a stem rebuke to the grandiloquently synthesized music in which it is trapped. "Backyard Ritual" begins with a few seconds of that pure and pent-up sound that changed the history of jazz. Miles's trumpet meanders mysteriously for a few bars, when a heavy funk rhythm impenously intrudes. The trumpet offers resistance, still straying. The volume of the beat grows stronger, the voice of the horn grows weaker. For a few moments the full difference between Miles Davis and George Duke, between the art of a master and the Muzak of contemporary "fusion," is plain. Then the middlebrow theme begins, the mystery is banished, and the trumpet surrenders. Miles sounds picked up and hauled away.

Crossover dreams? Crossover nightmares. Why won't anybody stick to their last? The good reason is this: the music. As Blades puts it in his film, "I got this music that I know could go a little further." But a closer look at the successful instances of such musical fusion shows that they work not when you cross over to the other side but when you bring the other side over to your own. The finest examples I know are the recent appropriations of American standards—the "avantpop"—by the mighty and slightly manic jazz trumpeter Lester Bowie. His accounts of "The Great Pretender," of "I Only Have Eyes for You" (exquisitely scored for eight brass instruments and a drummer), of Patsy Cline's "Crazy" are the essays of an artist secure in his strengths but restless, in love with where he lives but curious. There is a way to borrow, even steal, without compromising.

The bad reason for crossing over, of course, is the audience. It is also the most common reason. Domingo and Davis in particular give the feeling of following when they should lead. (Ronstadt, on the other hand, lost her way in trying to change taste; she was a pioneer of the new nostalgia.) Instead of waiting for popularity, they have gone in search of it. And so they have produced their first records absent of musical authority. This is the musical equivalent of market research. Indeed, what is crossover if not the application of a commercial idea to an exercise of art? In the music business you cross over not when you successfully expand your vocabulary but when you successfully expand your volume of sales. Paul Simon's Graceland, which weirdly mixes his lyrical urbanity with the obscure beauty of South African music, is not called a crossover, even though it is a wild juxtaposition of styles, for the simple reason that you do not cross over to something less popular.

Come home, Placido. Come home, Miles. And stay home. Heaven will be satisfied that you did one thing well. And there will be satisfaction on earth, too, in the praise of the hard-to-please.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now