Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowCAPTAIN DIVORCE

As the most sought-after and perhaps the richest divorce lawyer in the land, Raoul Lionel Felder has a client list that reads like a Who's Who of broken dreams. ROBERT MAYER pays a visit to the jolly lion of splitsville

With the sound of breaking crystal, lightning splits a celebrated marriage. High above Fifth Avenue, Raoul Lionel Felder slips into his monogrammed shirt, his monogrammed shoes, descends to his monogrammed Rolls-Royce. Before you can say "equitable distribution," this millionaire son of a poor Jewish immigrant is transformed into Captain Divorce.

The former $8,500-a-year federal prosecutor, who used to keep a hungry piranha in his office, has become the most sought-after divorce lawyer in America, and probably the richest. His list of clients reads like a Who's Who of broken dreams: the former Mrs. David Merrick, the former Mrs. Robert Scull, the former Mrs. Huntington Hartford, the former Mrs. Roone Arledge, the former Mrs. Alan Jay Lemer, the former Mrs. David Susskind, the former Mrs. Martin Scorsese, the former Mrs. Joseph Heller, the former Mrs. Frank Gifford, to cite just the tip of the cashberg. Helping to place the formers before such once promising futures has earned Raoul Felder a luxurious apartment overlooking Central Park, a second apartment, atop the Museum of Modem Art, housing his collections of books and old movie posters, a West Side apartment in which his college-age daughter lives, a retreat in East Hampton—complete with pool, boat, and moat—and a sumptuous house in Palm Beach that he has never seen. His firm bills between $8 and $10 million a year in divorce fees. And Felder, though he has seven lawyers on his staff, has no partners with whom he must share the profits.

"My adventures in the skin trade," he calls it. And he cruises through a storybook life alternately mocking and delighting in himself, his business, his clients, and his cash. "Sophie Tucker said, I've been rich and I've been poor, and rich is better," Felder says. "But it's a lot better." At the same time, he has an almost compulsive need to keep in touch with his poor Jewish roots in the Williamsburg section of Brooklyn, a heritage that bums in his brain like a temple light.

Apparent contradictions may be the ironic measure of the man. Color-blind, he owns 350 different suits; owning 350 suits, he dresses every Sunday in old army uniforms. A gourmet cook, he breakfasts on crackers and water and rarely eats lunch. Steeped every day in the detritus of divorce, he's been married to the same woman for twenty-three years. He` is feared and despised by many lawyers for his flamboyance and his no-holds-barred tactics in court, yet he is cherished by many of his former clients and by his staff, whom he presides over like a proud father and disarms with dry wit and broad high jinks.

In today's America, where half of all marriages end in divorce—often involving adultery, bitter custody fights, and fierce money struggles—it could be argued that the matrimonial attorney has the best seat in town. The only thing Raoul Felder seems uncertain of is whether he's watching tragedy or comedy.

Felder, fifty-two years old, a shade over six feet, slim, bearded, his dark hair thinning in front, is seated behind the cluttered desk of his large Madison Avenue office. Amid the piles of paper on the desk is a head of Balzac by Rodin. On the walls are paintings and drawings by Picasso, Rouault, Henry Moore, George Grosz. Scattered around the room, in display cases, atop tables, along the floor, is a motley collection of World War I hand grenades, edged weapons, Junior G-men badges, a huge china lion with bared teeth, various supermarket products that have achieved notoriety—a can of Bon Vivant vichyssoise, a box of Rely tampons, a bottle of Tylenol—anything that has ever appealed to Felder's offbeat sense of the absurd. In the outer office are old movie posters. One advertises Maureen O'Hara and Adolphe Menjou in A Bill of Divorcement. Another heralds Easy Money.

Felder removes his suit jacket. On the pocket of his beige shirt is a gold monogram, RLF. He leans back, puts his feet up on his desk, ankles crossed. On his winecolored suede shoes are gold monograms:

RLF. I ask about a comment made to me by an attorney for a major publishing firm:

"Divorce lawyers are the scum of the profession.'' Felder smiles. "That's like saying proctologists are the scum of the medical profession because of where they put their fingers."

I tell him what a lawyer who recently opposed him in court had to say: "Felder is a terrible, nasty, aggressive person.'' RLF grins. He won one victory by showing in court a pom film made on her lunch hour by the wife of a man he was representing. In another case, a bride of eighteen days came to Felder wanting to get out of the marriage because her husband, a prominent citizen active in charitable affairs, was forcing her to perform "unnatural'' acts. She had Polaroid pictures, taken with a self-timing device. Felder had one of the snapshots blown up to poster size and mounted on cardboard. Minutes before the trial was to start he took the opposing attorney, the late Roy Cohn, into a private office in the courthouse where the huge poster stood.

"Oh my God!" Cohn said.

"Isn't that disgusting?" Felder said, self-righteously. "Look what he made her do!"

The case was settled the next day.

The only thing Raoul Felder seems uncertain of is whether he's watching tragedy or comedy.

Felder relishes such dramatic conclusions. "The divorce business can be terribly boring," he says. "They've taken the romance out of it now with this influx of new laws across the United States—equitable distribution and community property. It's an accountant's game. I know how to play it well. But the lawyer's skill is gone. Clarence Darrow is dead. Today, lawyers don't know what to do in a courtroom. Their ignorance, their lack of life experience, is appalling. The law schools have ground everybody through the same sausage machines and they've got sausages—a generation of bookkeepers, businessmen, draftsmen, not advocates. When two lawyers sit down to negotiate and they have an understanding that nobody's going to go to court—because maybe nobody knows what they're doing in court and maybe nobody wants to get a heart attack—the victims are really the clients. Now, you may not like the adversary process, but we've stuck with it for four hundred years."

What Felder likes best is a bare-knuckled fight. He once represented a man who claimed his wife's life was being controlled by a psychic. Felder sent the psychic a woman who pretended she had the exact same birth time and place as his client's wife. "You have an astrological twin!" the psychic exclaimed. She advised the woman of every move to make in her life—the very actions she had directed the wife to take. At the trial, when the psychic denied she was controlling the wife, Felder asked if she remembered seeing an astrological twin. The psychic hesitated. Felder moved toward a tape recorder. The hired "twin" had been wired.

Last summer, in one of his rare nondivorce cases, he represented television correspondent Liz Trotta in a breach-ofcontract suit against CBS. When Felder came into the paneled conference room, he found a phalanx of dour CBS lawyers and senior executives seated around the table. After a few minutes of legalese from the opposing side, Felder decided that shock treatment was called for. Normally almost prudish in his language, Felder stood up and glared around the table. "We're talking about a woman's life and career here, not some contractual technicality. You fucked my client over," he said to the startled group. "But you're not going to fuck me over or I'll fuck you over in court!" Furious, the CBS people got up and walked out. Felder sat. A few minutes later, one man came back to negotiate. Trotta says she was "very satisfied" with the settlement.

Felder became a divorce lawyer in 1964. His success was instantaneous. "I was in the right business at the right time, and I had all the equipment," he says. "And everybody wanted a Jewish lawyer. You know, they hate Jews, but they wanted a Jewish lawyer.

"I say the right time, because society began to be disposable. And that started with television. Suddenly you had a generation that grew up thinking if you didn't like something you flipped it off. A guy is talking to you and you just turn the dial. People are disposable. Change channels. My parents were married forever; everybody was married forever. Today we live longer, we're able to survive serial marriages. We're able to support serial wives—or wives can support themselves. The institution of marriage is basically a failure in Western civilization."

About 60 percent of Felder's clients are women. Among the men have been Claude Picasso, the son of the artist; film director Brian De Palma; actor Richard Harris; and real-estate mogul Sol Goldman, whose estate was estimated in recent litigation at between $600 million and $1 billion.

"I was the first lawyer to break the $50,000 sound barrier for a fee in a single divorce case," Felder says. ''I was the first one to break the $100,000 barrier. And I was the first to break the million-dollar barrier."

The firm has more than three hundred divorce cases in the works at any given time. Felder handles about 120 of them. His involvement begins with a consultation in his office. Some wives won't reveal their names until they are sure they are going to retain him; the wife of a famous writer came for three visits without giving her name and became the subject of an office guessing game. A film director gave Felder his real name, but to the rest of the staff he was "Mr. Moto."

Face-to-face with distraught clients, he is empathetic. But, like a surgeon, he distances himself from their pain. ''Some of my fancy clients, their ancestors came over as a bunch of English criminals," he says. ''They own the world today. They're moral imbeciles. They're like the aristocrats of the French Revolution who ended up on the tumbrils."

Is divorce among the rich different from divorce among the poor? Felder zestfully proffers another quotation. "Kipling said, The colonel's lady and Judy O'Grady are sisters under the skin. And it's true. But the rich expect more. There's an intimate relationship between happiness and money with rich people. With the poor the crucial factor is survivability."

"We lawyers really are a parasitic profession. But so are accountants and psychiatrists. A lot of that is the illness of society. Why should people have to deal with my meat grinder in order to get out of some interpersonal problem? Why are we mucking about in people's lives? But the cash register keeps going here, so I'm like everybody else.

"Constant turnover, constant turnover," Felder says, rising, walking to the door, past the Rodin, past the Rouault. "Marriages breaking up as we talk. You wouldn't believe divorce pays for all of this."

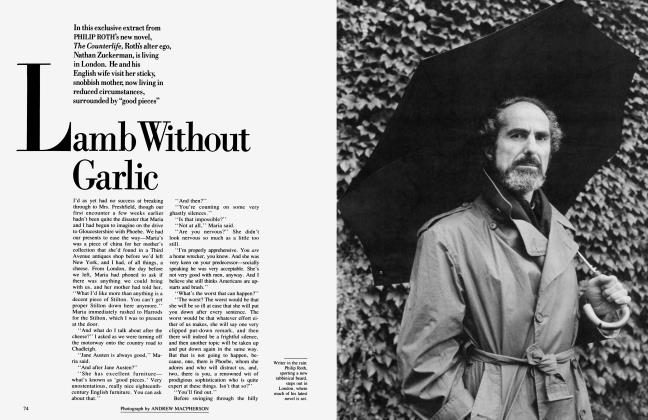

Felder's enchantment with old movies and private-eye novels is evident in a manuscript he recently began to write. The first chapter begins:

Her shoes spell money. Old money, new money, dirty money, cover-up-poor money—it's hard to tell until she opens up her mouth. . .. She wears a plain black sweater, Oxford-gray skirt, pearls (maybe real, maybe not). A small handbag at her side. She slides into a chair in front of my desk and finally looks at me straight on. Before she leaves that room I'll know more about her than her husband, lover, hairdresser, psychiatrist, or mother. She'll leave feeling confused, elated, smug, angry, or insulted. I'll be a little richer, potentially a lot richer, bored, or

excited. I'm a divorce lawyer—the best there is—and I've seen them all. . . .

It starts with a phone call. It always does. The telephone receptionist tells me over the intercom, New client—Mrs. Jackson, or Johnson, or Robowski, or—hopefully—Ford or Rockefeller. I pick up the phone and say, "How may I serve you?"

. . .They blurt out that they would like an appointment. I begin to play the game. Smooth and thick as lava flowing down a mountain, "What is the nature of the problem?" I ask, as if they thought I was selling window shades. They stammer that it is about divorce. I cut them off. Through a gracious smile I slither, "The consultation fee is $350.". . .

In that chair across from my desk have sat movie stars, schoolteachers, two-bit chiselers, the famous, almost famous, psychiatrists and cabdrivers, yesterday's news, Cabinet officers, gigolos, dykes and pansies, big-time crooks, crooked and honest politicians, people with dreams and shattered dreams. The leather seat can't tell one ass from another, and sometimes I have the same difficulty.

Such language! Such cynicism, from a nice Jewish boy! So Millie or Morris Felder might have exclaimed in their Brooklyn tenement apartment back during the Depression. But why, for that matter, did Millie and Morris Felder dare to name their son, back in 1934, Raoul Lionel? "Delusions of grandeur," Felder says.

Morris Felder came to America from Vienna as a boy, Millie Goldstein from England. Morris worked for a time hawking candy during intermissions at Brooklyn burlesque houses. Then he went to night school and became a veterinarian. "People didn't have dogs and cats in those days," Felder recalls. "He treated mostly horses that pulled wagons through the streets." When horse-drawn wagons were replaced by trucks, Morris went to Brooklyn Law School at night and became a ghetto lawyer.

"We were poor," Felder says. "We had enough to eat, but nothing for extras. We were always in debt. As a kid I was always skinny, always very cold, always shivering. I would look at all those cars in the car lots in the neighborhood and think how unfair it was. I could easily have become a Communist."

He says this from behind the wheel of his Sunday buggy, a bright-red Mustang convertible. His weekday car, a gray Rolls with gold-monogrammed floor mats, is driven by his chauffeur. It is Sunday morning and Felder is driving to the Lower East Side to Ratner's, the famous Jewish restaurant on Delancey Street, as he has done nearly every Sunday for thirty years, alone or accompanied by his daughter, Rachel, a student at Barnard. His wife, Myma, and their son, James, fifteen, do not care for the excursion.

At Ratner's he polishes off his one real breakfast of the week—a bowl of Wheatena, a plate of kasha vamishkes and potato pancakes. Then we slip back into the convertible, and Felder drives across the Williamsburg Bridge to his old Brooklyn neighborhood.

In front of a grimy city housing project he stops, the red convertible drawing stares from people passing by. "That's where I used to live," he says. "Only the building isn't there anymore. They tore it down to put up a slum."

Felder went to New York University, and later to N.Y.U. Law School. As an assistant U.S. attorney in the Eastern District of New York, he investigated counterfeiting cases, fraud cases, organized crime. The work was frustrating, rarely leading to a courtroom, and not very lucrative. Then, in 1964, an acquaintance going through a divorce asked Felder's advice. Felder took the case, for a fee of $5,000. He suspected that his client's good friend— the best man at his wedding—had been having an affair with his client's wife. The man admitted this in court.

(Continued Page 100)

(Continued from page 67)

Captain Divorce

"The tabloids picked up on the case," Felder recalls. "It was on page 3 of the Daily News the next day: BEST MAN KISSES AND TELLS. The phone started ringing. All the big firms began referring people to me because they didn't want to handle divorce cases—a dirty word in those days. That first year my income went from $12,000 to $70,000. But that's how it began—almost by accident really."

In the years since, he has become a leading authority on divorce law, has written two books on the subject, plus numerous articles in professional journals. He is now writing a book for the layman, on the sociological impact of divorce, with his assistant Jeanne Wilmot Carter.

While still a prosecutor, Felder met Myma Danenberg, a college graduate who was dancing on Broadway under the stage name Rawley Bates. After their marriage, Myrna went to law school. She is the current president of the New York State Women's Bar Association, and has an office in Felder's suite. She specializes in appeals law.

Raoul Felder is still gazing at the street where he grew up. Reluctantly, he begins to edge the car away. "Einstein was right," he says. "If we could move fast enough, we could catch up with the past. It's all still there."

I ask what he would do if he could catch up with it.

"I'd go back," Felder says. "It was a simple life. What do I need all this stuff? I'd go back." Then he corrects himself. "I'd want to visit, anyway. I'd want to visit."

Back in Manhattan, Felder cruises uptown for the next part of his Sunday ritual: prowling through flea markets, dressed in his Sunday regalia—khaki army pants, army shirt, olive-drab drill sergeant's cap, a fighter pilot's jacket. He settles on a movie poster to add to his office wall: Farewell, My Lovely. Moving on, he buys a forty-dollar bronze of the Devil holding a cloth spread wide. "I think what he's doing," Felder says, "he's waiting for the next sinner to fall."

A Thursday, a typical workday for Felder. He awakens at four in the morning after three hours' sleep. He's in the office by six. Piled on his chair is a batch of material left by the staff. He reads till 7:30, then begins to make phone calls. He may have to go to court to argue motions, but it's rare these days that a case goes to trial. He can usually intimidate the opposition into a settlement.

"What we used to call the white-shoe firms, the Ivy League law firms, have all gotten into the divorce act because this is big money today," he says. "But it's a little like. . .they asked Dr. Johnson what he thought of woman preachers and he said, Sir, you never think they can do it, and when they do it they never do it well. When we go up against a white-shoe firm, it's very good for us, because they're not really equipped for it. You can take 'em in about three rounds. Many of the large firms, maybe most of them, have the English sickness—they breed generations of idiots."

Felder works through the lunch hour. (He took his first vacation in twentythree years last October. He doesn't use his summer place in East Hampton because he can't endure the three-hour drive.) In the afternoon he calls a staff meeting. One of the lawyers, Susan Rubin, begins her report by saying, "I made a lot of money for you this month." Felder glances my way with a straight face. "I'm a pimp," he says.

He recalls an Italian count who retained him and let a huge bill pile up. The count said, "My family has been in Florence for fourteen hundred years, and you doubt my word?" Felder replied, "My family has been in Williamsburg for thirty years, and we want cash on the table."

Captain Divorce

Which reminds him of another Williamsburg story. Once, at a party, he found himself standing next to Lee Radziwill. ''I didn't know what to say. I wasn't brought up very social. I'd read an article she had just published about East Hampton. I said, 'Did you grow up there?' She said yes, and then she politely said to me, 'Where did you grow up?' And I said Williamsburg. And she said, 'Oh, it's so beautiful there.' And I said, 'Especially the nights.' I was thinking of the nights Puerto Ricans sat on the steps playing guitars."

The informal meeting breaks up. One attorney, Cindy Prusinowski, remains behind to reminisce about the divorce business: the time she chased Cheryl Tiegs through the streets in the rain to serve a subpoena, the day Claude Picasso showed up at the office in a Superman outfit, the night Felder personally served a subpoena on a well-guarded radio talk-show host by pretending to be a desperate listener bent on suicide.

One of Felder's most celebrated cases was the widely publicized battle over the art collection of Robert and Ethel Scull. In the 1981 divorce trial, Mrs. Scull, represented by another attorney, was awarded only seven minor paintings from the huge collection. She came to Felder for help. After several years of meticulously prepared appeals, the court awarded her a 35 percent share of the $10 million estate.

I mention a charge I'd heard, that divorce lawyers intentionally inflame their clients, breed hatred, to increase their own take.

"What we try to do is get people calmed down a little," Felder says. ''They're inflamed enough when they come to us. That is not to say there are not colleagues of mine who are legitimate crazies, who really have a need to do this. They have a need to destroy and threaten. And damage, and spew disruption. A lot of people who have these kinds of problems, this terrible anger inside of them, they gravitate toward the divorce business."

Felder looks at his watch. The gab session ends. He leaves his office, walks down the poster-lined corridor to the reception area. A woman is seated there, on a sofa, sitting up straight, wearing a yellow cotton dress. She appears to be in her late forties. She has brown hair that has not been coiffed. Her face looks haggard, drawn, as if she has not been sleeping well, as if she has been suffering some private hell. Felder reaches out his hand to the still-seated woman.

"Raoul Felder," he says. ''I'm sorry to make you wait. I'll be with you in a minute."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now