Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

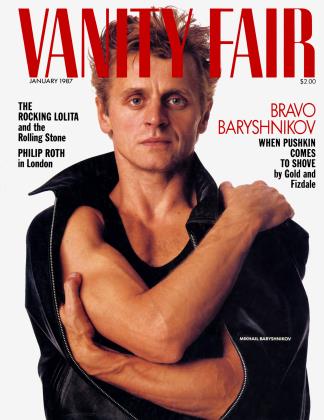

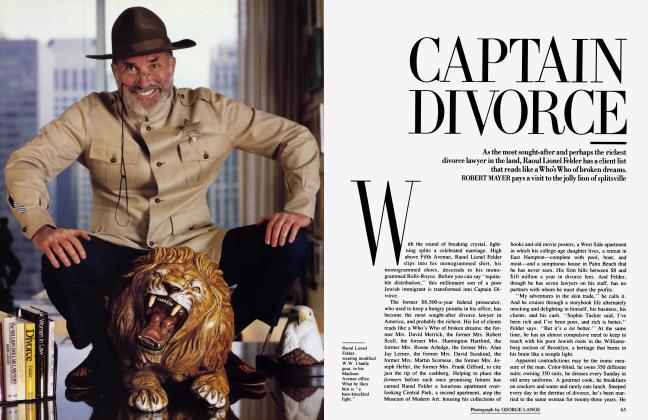

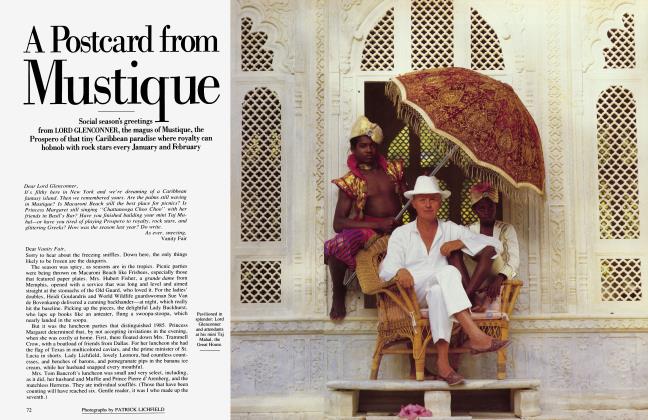

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowLike Balanchine before him, Mikhail Baryshnikov has embraced America. But while he wows the box office here, he remains at heart a melancholy Russian romantic. ARTHUR GOLD and ROBERT FIZDALE talk to their old friend at home

January 1987 Arthur Gold, Robert Fizdale Annie LeibovitzLike Balanchine before him, Mikhail Baryshnikov has embraced America. But while he wows the box office here, he remains at heart a melancholy Russian romantic. ARTHUR GOLD and ROBERT FIZDALE talk to their old friend at home

January 1987 Arthur Gold, Robert Fizdale Annie LeibovitzTo describe Mikhail Baryshnikov is like trying to catch a sputnik by the tail. Not just because he flies high and rushes in where angels fear to tread. Or that he is the elusive Slav one moment and the forthright American the next. Not because he is our greatest danseur noble on Monday and Twyla Tharp's syncopated comic on Tuesday. Or that he tends to dark Russian introspection in the A.M. and is all sunshine in the P.M. Nyet. Put these qualities together, add a little, subtract a little, and you still will not have Misha. For like all men of genius, he is far more than the sum of his parts.

A good deal of American ink has been wasted on Misha's tendency to brood. Of course he broods. Has there ever been a Russian artist who didn't? Nijinsky brooded, Massine brooded, Balanchine brooded. As for Gogol, Dostoyevsky, Tolstoy, Mussorgsky, and Tchaikovsky... Suffice it to say that Misha's temperature plunges lower than the average Anglo-Saxon's. But to speak of him without mentioning his gaiety, his puckish wit, and his blue-eyed playfulness is like making beet borscht without the beets. His imitation of Balanchine, for instance, complete with imperial air, nasal twang, sniffs, and nervous nose twitchings, is as devastatingly on target as a Daumier drawing.

At thirty-eight, Baryshnikov is the artistic director, primo ballerino, and inspiring force behind American Ballet Theatre. He is rich, famous, and busy. Yet unlike his great fellow defectors Rudolf Nureyev and Natalia Makarova, who bask in celebrity and revel in chic, like princes of haute couture, he leads the artist's life. His simple loft, a short stroll from Ballet Theatre's studios in downtown New York City, is filled with books, recordings, and drawings by Cocteau and Bakst. And a forty-minute drive in his Mercedes convertible (which he says apologetically is "a bit flashy") takes him to his Hudson Valley retreat and rustic anonymity. Recently he invited us to spend the day there. Oddly enough, we had once lived in a house close by, and had taken immense pleasure in the riverscape—for us the quintessence of nineteenth-century American Romanticism. But now, as we sat on Misha's terrace, high among the trees, the river below us, America melted away and we were transported to a cozy Russian dacha. Surrounded by five acres of wooded hills, ferns, and wildflowers, Misha leads a Turgenev-like existence—walking his dogs, fishing, dining with friends. Everything about the house suggests his homeland: the faithful friend and housekeeper offering copious amounts of tea and cakes; the framed photographs of his daughter, Alexandra—in riding habit, or playing the violin; the picture of Maxim Gorky; the Russian editions of Chekhov and Pushkin; the volumes of poetry and essays by his close friend Joseph Brodsky.

"I'm not a society person. I don't mind taking buses."

The day we visited Misha, with lunch, drinks, dinner, and a quiet evening ahead, we could not resist asking him about his past. Baryshnikov was bom in 1948, on January 27 (Mozart's birthday). "You know, I had a strange childhood," he said, speaking in his own telegraphic English, with its characteristically Russian omission of the's and a's. "I grew up in Riga, but I was Russian boy. My parents were considered aggressors, because in '45, after the war, Stalin occupied Latvia, which was independent country and very nationalistic. My father was very high in the Soviet army and taught military topography at academy. He was a typical product of Stalinism, very square, not very pleasant. And I knew we were not loved. Somehow it forced me to ...masquerade. At that time I spoke Latvian as well as I spoke my own language, but still you could see I was Russian boy, blond, small, with typical Russian mentality and body. Even the way we Russians dressed was different. The Latvians used to wear a lot of homemade clothes, more like Scandinavians. Clean. Wool. They had good Jewish tailors who made nice Western cut. The Russians wore anything they could find in the stores.

"Father was very nationalist Russian, a big anti-Semite, and he didn't like Latvians either. For him it was les Russes über alles. I felt really embarrassed, as all my friends were either Jewish or Latvian people. Many were musicians, different somehow. I didn't want to invite them to our home, afraid my father would insult somebody.

"My mother was completely different. She was extraordinary. Not educated at all, but very beautiful: tall, blonde—stunning. Very soft. She had a provincial accent, but her voice was like melody. Uneducated as she was, she went to the opera, all alone. Didn't even know what they're singing. She took me to my first theater. Without Father. Opera and ballet too: Don Q., Giselle, Traviata. I could hardly sit through the opera, but I enjoyed the ballet. It was more colors there, and people moving.

"At that time I played a lot of sports, different ones like gymnastics, fencing, or soccer. Then, you see, I started dancing in grade school and high school. After classes, there's a group of boys and girls who do folk dancing for an hour. It was actually, you know, part of wanting to meet girls, and not just in the corridors. You go, and it's music playing and everybody's learning to dance, and you have to hold her in your arms, and dance around. . .You could really talk to young girl. And it starts. You know, courting, kind of, and I somehow was good in that.

"When I was around ten, eleven, I decided to try for choreographic school. I went without any pressure from Mother and passed examination. Father was really perplexed, and said, 'What! You really want to be a dancer!' I understood his objections, but I was not a good student and hated school. Is O.K., some subjects, like history and literature. But arithmetic and algebra! Terrible! I probably missed the first rules of the game and got behind. I cheated and lied just to avoid homework. It was embarrassing for Father. Then my mother died and I lived with my father and got a little better at school. Anyway, we only met at breakfast and couple of hours in the evening.

"I decided to be a dancer because I had a very good, very wonderful relationship with my teacher. He was a young dancer, Yuris Kapralis. Alexander Godunov was in the same class. Kapralis was very, very smart and gave me my first actually good technical foundation—age twelve, thirteen, fourteen. Elena Tangieva, the head of the ballet company, also helped me. But it was a provincial school, and at fifteen I left and went to Leningrad. I wanted to see more. Also, I had heard of Alexander Pushkin, Nureyev's teacher. I had a ballerina friend who now teaches in Paris. She said, 'Let's go meet this man,' and I said, 'Just help me. Let's go!' We went. Pushkin and I had long talk and he examined me. I didn't even dance for him. I was just privileged and lucky that he had a class for boys my age. I never went back to Riga.

"Leningrad was a shock. I had to work from eight in the morning till eleven at night, and pass all exams: French, geometry, piano lessons. First few months I got really paranoid and thought I wouldn't make it. But then I realized I'm doing well with the classical dance.

"My teacher Pushkin was not terribly educated man. He had a good eye for what's right and what's wrong, but he couldn't explain. Just didn't like it. There's jokes about him. They say he had only two corrections: 'Don't fall!' and 'Get up!' Sometimes saying 'Don't fall!' at the right moment is worth more than detailed explanations of pyrotechnics.

"The timing of the class was extraordinary. It gets into you. Very good warm-up and then suddenly the pressure starts and the combinations get harder and harder, harder and harder. And then at end of class, leading dancers did their variations. Wonderful!

"I spent all my time with my teacher and his wife, because he kind of adopted me. I lived with them part of the time and they fed me. I worked day and night. Sometimes after dinner he would say, almost teasing, 'Well, how about forty-five minutes barre and twenty minutes of jumps?' And I did my barre alone while he went for walk on Nevsky Prospekt. Then he would come back and give me long variations. After that we walk for twenty, thirty minutes, back and forth, back and forth. Then it's time for bed. And the next day it's the same. Hardly any going out with girls. Or if I did, it was very much innocent high-school stuff. I never. . .There was no time.

"Pushkin always believed I would be a classical dancer, not a demi-carac-tère. Nobody else thought so, because I was so tiny, with baby face. But he said, 'Just keep going, keep going.' He gave me incredible love. This man was the sweetest, sweetest. . . "

Of course he broods. Has there ever been a Russian artist who didn't?

In 1966, under Pushkin's guidance, Misha won top honors in the Varna Competition, and three years later was awarded a gold medal in Moscow. By then he was a member of the Kirov Ballet. In 1970 he was sent to London, where the public and critics immediately recognized him as the phenomenon he is. It was about this time that he fell in love with Natalia Makarova, the troupe's prima ballerina. She was married and not as involved with him as he was with her. In any case, she was soon to leave both Misha and her husband behind to seek a career in the West.

Fortunately, Misha had friends to turn to in his sorrow. "I had very close, very intimate relationships," Misha remembers. ''It's very different in America. Here, if people don't feel right, they don't feel right in advance because they have an appointment with a shrink not to feel right. Over there is nothing like that. You either deal with your problems by yourself or you go to a very close friend and talk, just talk and talk. If you want to talk politics you make sure, a thousand percent sure, that the person you are confiding in is not working for the K.G.B. And then you whisper. You talk about your conflicts, or love affairs, or something terrible that happened in your life. Good friends, they can call on you in middle of night without telephoning. Just open the door and say, 'You know, I feel terrible and I'll stay with you for a while.' Sometimes that means for a couple of weeks or whatever.

"You get no information in Soviet Union. Not even magazines. And so you read every page of Vogue, or other fashion magazines that somebody smuggles in, from beginning to end. You even read who is editor and you remember the names. And there is a black market for art books, just like for underground literature and poetry. Somebody arrives from abroad and the first few nights they don't sleep, because their friends just move in and read and read the forbidden books."

On the evening of June 29, 1974, Baryshnikov, who had been sent to Canada as a guest star with a second-string troupe from Moscow's Bolshoi Ballet, appeared in their final performance in Toronto. The tour was the first occasion since Makarova's defection in 1970 that he had been allowed beyond the Russian border, and he was under strict surveillance. No one in the audience could have imagined that the dancer acknowledging the wild applause with aristocratic composure had spent the afternoon planning to escape. Yet a few hours earlier he had met with friends in a ''safe" suburban house to discuss the scenario for his defection. Strangely enough, he could have remained there and asked for asylum with no further risk; instead, he decided to go through with the evening performance, saying it was unfair to leave his fellow dancers in the lurch. Dostoyevsky-like, Misha chose to go back into the Russian net.

The schedule for his defection seemed perilously simple. The final curtain would come down at 10:30. A Russian friend and a Canadian who had volunteered to drive would be parked in front of a restaurant near the theater. They would take him back to the house in the suburbs. A quick switch to another car and on to a hiding place in the country.

But it was not that easy. The curtain refused to function at the beginning of the program, which caused a delay of fifteen precious minutes. The ovations took much longer than usual. And to heighten the tension, Baryshnikov was told, in no uncertain terms, that he was to attend an official reception immediately after the performance. He was now more than a half-hour late for the rendezvous. When at last he opened the stage door, a hallucinatory sight greeted him. Beyond the huge crowd of eager fans, two K.G.B. "baby-sitters" were waiting to drive him to the party. He was cornered. He could step into their car and go on with his life, or he could make a dash for freedom.

Suddenly, instinctively, he plunged through the throng of autograph seekers, ignored the Soviets' shouts of "Misha, where are you going?" and raced blindly down the street, narrowly avoiding an oncoming car. He cut across a parking lot and was running toward the restaurant when he was spotted by his friend, who, frantic at the delay, had come to see what was wrong. Two hours later he was in an isolated farmhouse, far from the city. Late that night, drunk on vodka and excitement, wild with laughter one moment, shaking with nerves the next, Misha telephoned Makarova, who promised to arrange an engagement for him with American Ballet Theatre the following month.

On July 27, when Baryshnikov made his New York debut as Albrecht to Makarova's magical Giselle, it was clear that a great artist had come to shed new light on the dance. It was not only the unparalleled grace and beauty of his virtuosity that won him a thirty-minute ovation, dozens of bouquets, and delirious chants of "Misha, Misha, Misha!" His gifts were far beyond mere pyrotechnics. Here was a presence, a dancer whose every swelling leap, every turn, gesture, and facial expression, was at the service of his art. He was there to express, not to impress, to show us a perfect fusion of classic line and romantic color, to respond to the music with every impulse of his physical being. It was baffling, exhilarating, ravishing.

A few days later we met Misha for the first time—in a swimming pool on Long Island. He dived in, swam the length of the pool underwater, popped up for air, and, with a brisk military nod, introduced himself: "Baryshnikov!" The dancer-turned-water sprite was visiting our friends Henri Doll and his wife, Eugenia Delarova, whose boundless hospitality is legendary among such emigres as Nureyev, Makarova, and the Rostropoviches.

He is our greatest danseur noble one day, and Twyla Tharp's syncopated comic the next.

That weekend Misha was all Slavic charm. Russian through and through, he was warm, witty—and an instant friend. Announcing that he was a "fisherman by profession," and that dancing was just a hobby, he spent the mornings catching dozens of illegally small striped bass. No one had the heart to dampen his newfound sense of freedom by telling him to throw them back. He would present his catch to the Dolls' cook, then minutes later, a big grin on his face, he would rush down to the beach balancing a platter of freshly fried fish high in the air like a waiter in a crowded Paris bistro.

Such happy moments apart, Misha was desperately homesick and longed to go back to Leningrad. He wished he could "walk invisibly around the streets, see that it's all much worse than I remember, and be cured of nostalgia." Instead, he found solace in hard work, and impressed even himself by performing twenty-six roles in the next two years. "Not bad for a beginning," he said. "In Russia such an achievement would cover my entire artistic life." A speeded-up movie montage might show Baryshnikov dancing to cheering audiences in the great capitals of the world, then suddenly making a dramatic move in the midst of his triumphs.

To the astonishment of his admirers, in 1978, after four years at A.B.T., Baryshnikov joined the New York City Ballet in what was called his second defection. As the name implies, Ballet Theatre was the home of dance drama. It emphasized expensive international guest stars, elaborate sets and costumes, and popular story ballets. In contrast, the New York City Ballet put its emphasis on Stravinsky and Webern, Mozart and Tchaikovsky, as seen through the abstract, uncompromising eye of George Balanchine.

For Baryshnikov, the commitment to N.Y.C.B. was "like a marriage. I feel as if I'm in a church, and in church you do not think of divorce." Nor, he might have added, do you think of money. Misha received from three to five thousand dollars a performance at A.B.T., and even more when he took guest engagements with other companies. Now he would earn a mere $750 a week for the privilege of being an "instrument" in Balanchine's hands.

Baryshnikov had said that one reason he left Russia was to work with "the two greatest choreographers in the world, George Balanchine and Jerome Robbins." Robbins had already made his seductive Other Dances for Makarova and Baryshnikov at A.B.T., and would create Opus 19/The Dreamer for Misha at N.Y.C.B. Although John Taras, then one of Balanchine's ballet masters, said that he "had never seen Balanchine work in such detail with any other dancer," the great choreographer was never to make a ballet expressly for Baryshnikov. He was seventy-five, in failing health, and had no desire to disturb the composition of his company. "Besides," he told us at the time, "I can only give Misha two or three big roles, Apollo, Prodigal Son, and maybe few other things." And so it was with a certain reluctance that Balanchine had accepted Misha into N.Y.C.B.

It was not that he disliked Misha. On the contrary, he said he was like a son to him. Unfortunately, Balanchine was a problem father. He had a streak of Russian cruelty and a contrariness that made him bend over backward to show that, while Misha might be the greatest male dancer in the world, he was not prepared to favor him over any other newcomer. It was an insoluble problem. The choreographer had devoted his life to the creation of a cohesive troupe that reflected his innovative ideas of style, technique, and musically. And Baryshnikov was a fully formed artist trained in the tradition that Balanchine had gone beyond. Challenged by these difficulties, Misha knuckled under. But with all his deference and his epic willingness to work, he was not suited to Balanchine's "cool" classicism.

Baryshnikov spent fifteen months with N.Y.C.B. And just as Balanchine had predicted, he was a dynamic Prodigal, a superb Apollo, and a more than delicious commedia dell'arte figure in Harlequinade. But it was sad for his admirers to see him diminished in roles that less brilliant dancers handled with ease. And sadder still to realize that had Balanchine been younger, he might have created ballets which would have allowed Baryshnikov's ardent, impetuous romanticism, his demonic virtuosity, to shine. "He had a very tough time," remembers Peter Martins, the dancer who now co-directs N.Y.C.B. with Jerome Robbins. "The critics were really rough on him. They didn't let him breathe. And here he was, the most prominent dancer in the world. He even surpassed Rudy [Nureyev]. Misha's gift is so immense. And he has the most interesting body I've ever seen on a male dancer. His proportions are immaculate. Very beautiful legs, the most unbelievable feet. But he was not a prima donna on any level. There was something very earnest and sincere about him."

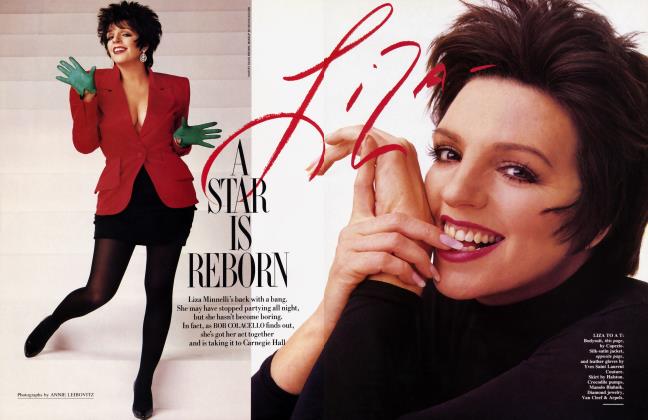

In September 1980, Misha left N.Y.C.B. and became Baryshnikov the superstar once again. Soon after, he accepted the artistic directorship of American Ballet Theatre, a position not without its thorny problems. There is a $16 million budget to administer, contentious corporate board members to cope with, a hundred dancers to nurture. And he continued to dance himself—for Twyla Tharp, for Paul Taylor and Eliot Feld, for his own company. He danced with Liza Minnelli on TV and with Gregory Hines in the movies. He even did a pas de trois with two nine-hundred-pound whales in their tank at San Diego's Sea World. He acted. He sang.

Despite his celebrity, Misha is apt to be bashful. "I'm not a society person," he affirms. "For instance, I don't mind taking buses. But if you're stuck in one, nose-to-nose, with a stranger, and they say 'Hi! Hi!' you have to talk. It's like being in aquarium. At least when you're in your own car you pretend to listen to music or look over there, just to avoid eye contact. Some people go on the street, like Rudy for example. He loves it. He looks at them as though to say, 'Well? You recognize me? Then talk to me or I'll start.' We used to go to restaurants or clubs, here or in London. He arrives and looks around—at everybody's eyes. And I, I can't look at a girl—you know, below the shoulder. Except on the stage. Then I look. I can't work without real eye contact."

Eye contact or no, Misha is a notorious success with women. As Twyla Tharp says, "Misha is very attractive. He doesn't put it on; he just is attractive." Indeed, he is possessed by romantic feeling, even onstage. "I always have to imagine I'm dancing for somebody. It can be empty studio, but I'm dancing for someone I love. It can be my daughter. Or I'm courting some pretty girl and maybe it will happen tonight. Maybe after performance. But most of the time it's not that I'm thinking of anyone in particular. It's that someone is somewhere in my thoughts—vague, but there. I'm not trying to remember her, like Actors Studio—God forbid! It's not necessary in ballet."

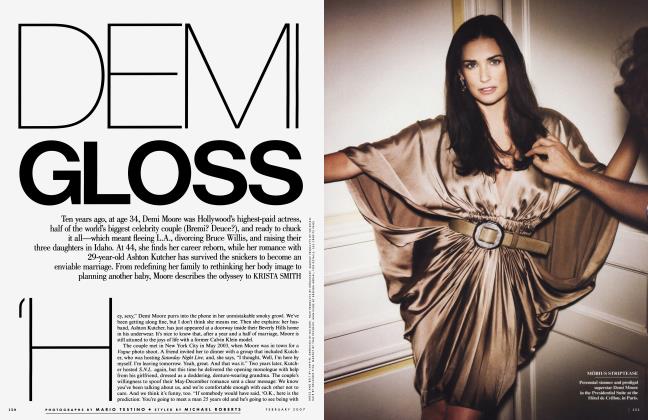

Misha, like Balanchine, loves beautiful women. But unlike Balanchine, who married five times, he remains a bachelor. He had a long love affair with Jessica Lange, who gave him a daughter he adores—and later left him for the actor-playwright Sam Shepard. It is said that Lange broke his heart. Perhaps it was that experience which prompted him to say, "I prefer European women; I don't understand American women." Nor do some American women understand him, as anyone who has read Gelsey Kirkland's recently published memoirs will find. Misha's former dancing partner, who calls her book Dancing on My Grave, might have considered calling it Dancing on Other People's Graves. Its pages, filled with self-hatred and resentment of others, do no one justice, Misha least of all. When asked if he had read it, Misha is reported to have said, ''I haven't even finished reading Sam Shepard's plays yet." He was amused when we told him that under similar circumstances Lord Byron wrote that " 'kiss and tell' bad as it is" is not nearly as bad as "f— and publish."

Baryshnikov resents being called a Lothario. Yet perhaps his most memorable role is that of the classic Lothario —the fickle Albrecht in Giselle. This spring it will be fascinating to see a close-up of his interpretation of the part in a new Herbert Ross film, which focuses on present-day dancers working on a new production of the ballet. The movie will frame—and permanently—Misha's superb dancing, and will also give him further opportunity to prove something he is reluctant to admit: his powers as an actor. He laughed uproariously when we assured him that he was already considered a movie star. Yet his modesty is understandable. As a dancer who worked so long and hard to achieve perfection, he finds it difficult to believe that film success can be won without the kind of arduous academic training he received at the Vaganova School of Ballet in Leningrad.

"But I'm getting used to films," he said, "although it's frustrating and very scary. I've been studying with Sandra Seacat, who taught Jessica. We talk about the camera and what I do and why. And how to deal with problems, especially since I'm not professional actor. I know I have certain qualities the camera likes. In fact, I'd like to do a movie with no dancing, just out of curiosity, to see if I could hold a role. Not even a lead, just a cameo. Whatever. But it's scary."

For Misha watchers, his future is a matter of great concern. Twyla Tharp, who created what we like to call her Pushkin Comes to Shove for him, and with whom he loves to work, understands the problem as well as anyone. "He's mystified," she says. "He's always thought he wanted to stop dancing. From the beginning. Always. But giving up dancing, giving up the addiction to movement, is very difficult. It will be a while before he can break the habit. He's had an incredible education. He's a very good teacher and a fabulous coach. He's unique. When I saw him in Swan Lake with Natasha Makarova, I thought, This is it. No one else can touch what these two have. He's thirty-eight; he could have five more good years. But if he doesn't pass on this great dance tradition, it will shortchange everybody."

It is wise when speaking of Misha's future to think of his past accomplishments and his present daring. He defected from Russia to seek artistic and personal freedom—and succeeded in finding both. He became a dance idol and a popular hero. He has shown time and again that he can land on his feet as securely in life as in dance. Why worry? The future is his.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now