Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

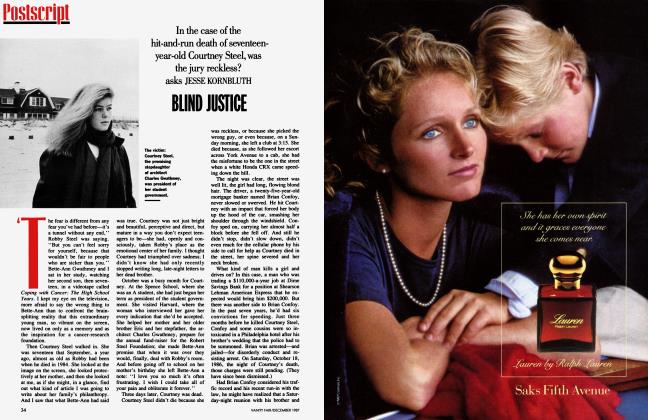

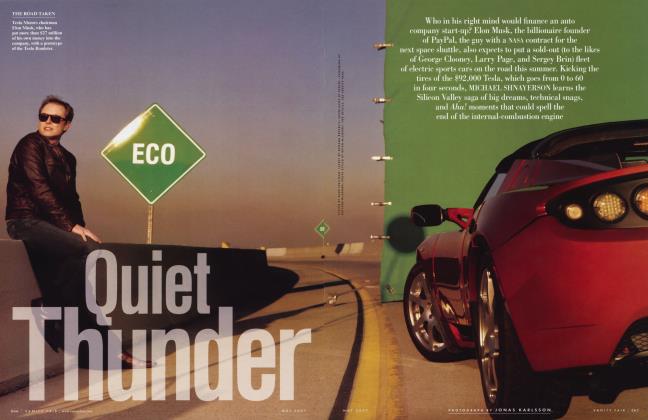

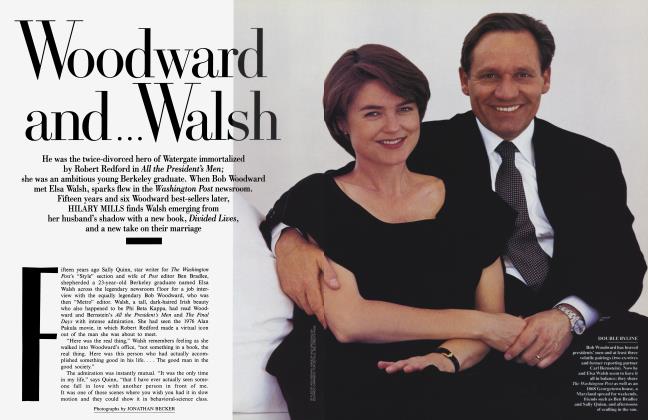

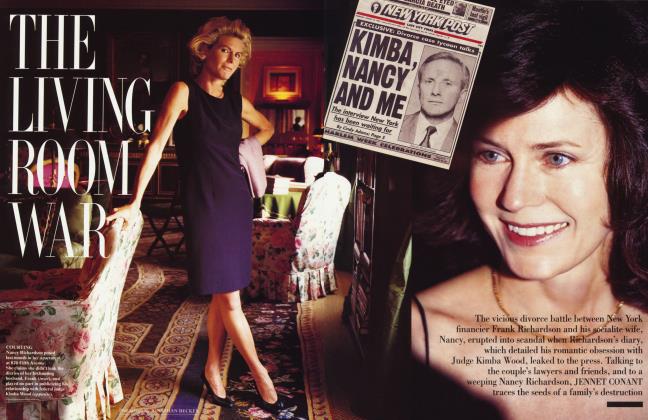

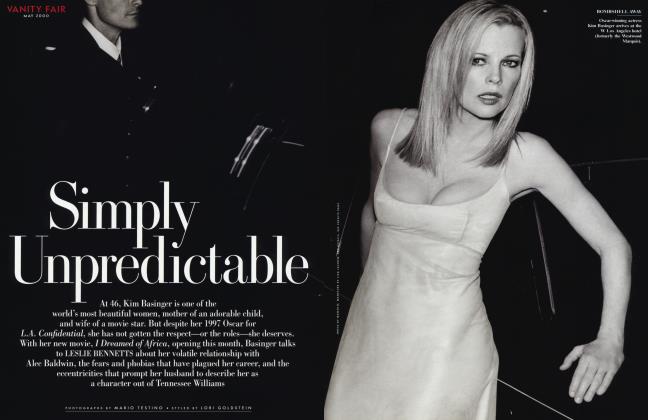

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowEach year, some new power socialite blazes across the New York heavens. Marifé Hernández, one of the few Puerto Ricans on the charity circuit, is determined that 1988 will be hers. She's fiercely entertaining Democratic candidates, positioning herself as the next heavyweight hostess. And, as MICHAEL SHNAYERSON finds, her drive gives off a lot of heat

December 1987 Michael Shnayerson Jonathan BeckerEach year, some new power socialite blazes across the New York heavens. Marifé Hernández, one of the few Puerto Ricans on the charity circuit, is determined that 1988 will be hers. She's fiercely entertaining Democratic candidates, positioning herself as the next heavyweight hostess. And, as MICHAEL SHNAYERSON finds, her drive gives off a lot of heat

December 1987 Michael Shnayerson Jonathan Becker'Miss Hernandez not here. You wait?"

The butler retreats through the chandeliered foyer, the dining room beyond.

I take a slow look around. In the living room: overstuffed sofas and chairs in blue and coral chintzes and silks against yellow striped silk walls. Elegant and yet a bit....extreme. In the library: wood-paneled walls, a pair of large Miro paintings. And in the dining room: another Miro— huge, this one—and a seventeenth-century Spanish-colonial painting of an angel with a gun. A Latin sensibility, make no mistake about it. But there's an Upper East Side edge here as well.

Again the butler answers the door. In comes Hernandez's aggressive new public-relations man, Arnold Jurdem. What does it say about Marife Hernandez that she's hired as brash an operator as Jurdem? Hernandez, after all, has always been good at promoting herself. She made her name in the Carter years as the State Department's chief of protocol in New York, entertaining the likes of Margaret Thatcher and Pierre Trudeau and Queen Beatrix of the Netherlands. More recently, she was mentioned as a possible successor to Bess Myerson's scandal-ridden post of New York's cultural-affairs commissioner. She sits on half a dozen boards, including those of the Metropolitan Museum and the Americas Society and the Spanish Institute and New York Hospital—power boards, every last one of them. She gives and goes to elegant dinner parties in New York and Southampton. She counts David Rockefeller among her closer friends. In part because she's indefatigable, in part because she's virtually the only Puerto Rican on the charity circuit, everybody seems to know Marife.

High heels come clicking across the dark wood floor. At forty-eight, Marife Hernandez is rail-thin, redheaded, and razor-sharp.

I ask her what she's up to.

She ticks off the next week's social events with all the crisp efficiency of a general declaring battle plans. "Tuesday, the dinner at the Americas Society—"

"With the Rockefellers," Jurdem interjects. "David's the chairman, Marife's the vicechairman."

"Wednesday, dinner with President Carter at Alice Mason's. Thursday, my dinner here for Luis Noboa—"

"The banana king of Ecuador," Jurdem explains.

"The Cisneroses will be there. Shirley Lord and Abe Rosenthal, Ambassador Enders."

Right on cue the phone rings: it's Hernandez's social secretary with the news that Ambassador Enders won't be able to make it, he's traveling. Though his wife will still come. Now: whom to get as an extra man?

Hernandez frowns as she holds the phone to her ear. "Mario?"

"Nah, not Mario," Jurdem calls over from the sofa.

"Henry, if he's in town," says Hernandez to the phone.

Jurdem calls, "I can get you what's his name, the richest guy on the Forbes list.. .what's his name? David Koch."

"Oh, no," purrs Hernandez to some other suggestion from the secretary on the phone. "That would be perfect."

"The real question is why," Jurdem prompts Hernandez. He turns to me. "I mean, she's got money, her husband has more money, and so why...?"

"Last May," Hernandez starts in, "Senator Cranston called me and said, 'I need your help.' He came to my office, he had this little map colored with crayons, and he talked to me about voter registration."

Alan Cranston wanted to start a nonpartisan group called USA Votes. In California alone he wanted to register one million new voters. So Hernandez vowed to do the same for New York.

"I have to start the New York Votes committee; so far it's got four members. It's a lot of calling, getting senators and congressmen to come for meals with small groups. I'm contributing a lot of money, and I am raising a lot of money.

"At the same time—and you're going to say how can you do both and be nonpartisan—I want to elect a Democratic president of the United States. I'm a member of the National Finance Council of the Democratic Party, and I'm a trustee of the new victory fund that we just started. The party is raising it for whoever becomes the candidate."

That's where the dinners come in. Hernandez is planning to host a series of dinners in New York for the various Democratic candidates and potential big donors. It's good politics, all right: 1988 could well be the Democrats' year, and in the New York social world, an awful lot changes with an outgoing Republican president and an incoming Democratic one. True, not as much as in Washington, but still: New York Republican hostesses can no longer entertain the politically powerful (only the rich, alas). And certain Democratic ladies rise to the top. In the Carter years it was Alice Mason, a personal friend of the Carter family—and Marife Hernandez. This time, with an early start on candidate dinners and the help of Mr. Jurdem, it could be... Marife Hernandez.

A little after eight P.M. the next Thursday evening, a midnightblue Mercedes limousine rolls up to the curb outside Hernandez's East Side apartment. The driver jumps out and runs around the back to open the passenger door. David Rockefeller emerges, in black-tie, carrying a five-foot-long inflated plastic iguana.

The Rockefellers, David and Peggy, walk into the lobby, the iguana between them. As they wait for the elevator, they're joined by the evening's guests of honor, Banana King Luis Noboa and his wife, Mechita, and another couple. The elevator arrives, and everybody piles in, packed so tight that D.R. has to hold the iguana to his chest and is buffeted on all sides by bejeweled bosoms. As the guests spill out, Marife Hernandez makes a beeline for D.R., ignoring, for the moment, everybody else. D.R. gives her the iguana with a smile. He explains that it's a souvenir from his just-completed trip to the Galapagos Islands. He is—or certainly seems to be—enjoying himself.

Not Marife Hernandez. Her evening dress is festive enough, as festive as the living room that serves as its backdrop, with an unmistakably Latin flair. But her eyes belie the smile. Behind her stand a bevy of black-tied South American ambassadors and their wives; squirrelly Abe Rosenthal and Shirley Lord; a gossip columnist from the Daily News; and Arnold Jurdem. As Hernandez puts the iguana in a corner of the living room and moves on to her other guests, you can almost hear her mind, like her high heels, clicking. Levity is not her style.

Marife Hernandez has been married, by her own admission, four times. Alan Alpern, sixty, is her latest. Alpern is one of those private investors who talk vaguely of oil and gas and telecommunications, of making a few good deals a year and establishing little companies here and there. A square-jawed fellow with silvery hair, Alpern is also a member of the Council on Foreign Relations, and once worked for the State Department. "But his real passion," says Hernandez, "is inventing. He's got several patents; right now he's working on a safe cigarette."

The two met some eight years ago at an Alice Mason dinner party. Each was married at the time, and the two couples became social friends. After Alpern's wife died and Hernandez got divorced, they married, in 1985. The only question then, with their respective children grown, was what to do with all the real estate. They made a trade-off: Hernandez gave up her house in Water Mill to move into Alpern's Southampton place, and Alpern gave up his New York apartment for Hernandez's more respectable East Side address. I ask if they like to just laze around when they get to the country—put on a pair of jeans, open a couple of beers, cook hamburgers. The two of them look at me as if I've lost my mind.

"I have a very good staff," Hernandez explains. "If the wife works, a staff is essential. Because when Alan gets to Southampton tonight, Alan does not want to stop somewhere and have a lousy dinner. He doesn't want to go home and have to change and go to the club. What does he want to do?"

I draw a blank.

"Alan wants to go home and have a wonderful dinner in our house, walk around, look at our roses—he looks at his vegetables, I look at my 115 rose plants. And then we have wonderful drinks. And then we have a wonderful dinner." Hernandez raises a long-nailed finger in the air. "There's someone out there right now making that dinner."

"Lots of people," Alpern choruses.

When I ask Hernandez about her other husbands, she allows that her first was a lawyer named Tom Corvan. But she begs off mentioning the others, because they're part of her past, after all. "I'd just say I like men who like commitment," she avers.

A profile in the New York Times in 1980 described her second husband, "Foxy" Carter, as a career foreign-service officer from a Main Line Philadelphia family. Her third, as friends are quick to confirm, was Paul Hallingby Jr., an investment banker.

All well and good—except that the Times story listed her first husband as Henry Sanders and made no mention of Tom Corvan. More confusing, Hernandez's twenty-two-year-old daughter Sasha, who bears Carter's name, was described by the Times as having been born of the Sanders marriage. That, I assume, must be a simple mix-up. Until I stumble on another husband, named Hack Hoffenberg—the fifth husband, the one Hernandez has tried to excise from her past for the last twenty years.

"Marife lives in a dreamworld, and part of the dream is that I don't exist,'' says Hoffenberg, sixty-five, who now buys and sells Latin-American art.

"I was married to her for seven years, from about 1962 to 1969," Hoffenberg continues, "after Tom Corvan, who was her first husband. There wasn't any Henry Sanders—she took the name from a good friend of mine, Henry Sage. And Sasha—whose real name is Alexandra—is my daughter.

"We had a perfectly good marriage," he says, "except that I had no real money or social position. And, of course, I was Jewish."

Hoffenberg at the time was importing leather goods from Brazil and making a decent income, he says, but when Hernandez met Foxy Carter, she bolted. Hoffenberg still lives in the East Side apartment he and Hernandez shared in the 1960s—just four blocks from the one Hernandez lives in today, the one in which his daughter grew up.

Queried about all this, Hernandez admits she has had five husbands. "But Tom Corvan died when I was twenty years old," she says. "It was a very sad thing, so I don't include him."

Marife Hernandez was born the only daughter of a wealthy Puerto Rican family, and grew up in Argentina and Uruguay for the most part. Her late stepfather was an economist, her mother (who divorced Marife's father when Marife was young) now owns commercial real estate in Washington, D.C. Marife attended Wellesley for two years, she says, then left to study at the American Academy of Dramatic Arts. In fact, the academy's carefully kept files, which go back a hundred years, show no record of her there. Pressed, Hernandez says she enrolled as Maria Corvan, but that name, too, fails to check out.

She did enroll at Columbia University's School of General Studies to take political science, but dropped out in her senior year. It was in 1966, while married to Hoffenberg and living in Brazil, that she put together a New York show of work by her Brazilian artist friends and discovered she liked, as she puts it, being a doer. Two years later, back in New York, Hernandez presented herself at WPIX-TV as a prospective host of a talk show about Puerto Rican life in the city. Impressed by her gumption, the station manager gave her a Sunday-morning slot to try a show called The Puerto Rican New Yorker. Her marriage to Hoffenberg nose-dived, but the show took off.

That, and the other WPIX talk shows that followed, became her first power base. In 1976 Hernandez invited a little-known presidential candidate named Jimmy Carter onto one of her shows.

Hernandez has become a controversial character, even to those who don't know her whole story

The two got along well, Hernandez pitched in on the campaign, and President Carter awarded her a newly defined post as chief of protocol in New York. Her third marriage—to Foxy Carter—collapsed soon after.

As plums go, the protocol job might not have seemed the ripest. Hernandez received a $45,000 salary, but had no expense account to help defray the costs of frequent entertaining. The only other tangible compensation was the little place cards embossed with the U.S. State Department's seal that adorned Hernandez's dinner tables. But if social clout is less tangible, it's certainly no less real. Hernandez entertained heads of state. She became a fixture in the national Democratic Party. She earned points as a tough and tireless social fixer, a middleman between foreign politicos and American bankers. She had drive, and she was proud of it. "I believe that you're born that way," she says today. "I believe that drive is one of the most given or not-given things." She also had style. She knew how to make a dinner party work, what to serve and how to serve it, how to spend no more than a moment or two with any one guest, and afterward, often with mariachi bands playing, how to dance. "I remember her dancing," says a friend from that time. "She and her partner were like a single piece of paper fluttering across the floor."

By the time the Democrats were swept out of office, Hernandez had set up her next move. She'd parlayed her new friendship with Margaret Thatcher into the start of a project called Britain Salutes New York, a piece of unprecedented cross-cultural puffery in which hundreds of British exhibitions of fine and performing arts were hauled across the Atlantic in 1983. Both sides indulged in a frenzy of cocktail parties and self-congratulation, all coordinated by Hernandez and her staff.

Meanwhile, Hernandez and the festival's advertising agency, Ogilvy & Mather, had started a for-profit cultural public-relations department, wooing such clients as American Express and the British Tourist Authority. Then came a better opportunity: Coca-Cola wanted to improve its share of the national Hispanic market. Because O&M handled foreign advertising for Pepsi, Hernandez went out on her own as a consultant for Coke. She still holds the job, though one high-ranking Coke executive doubts that she's been much help. "Marife set herself up as a liaison to the Hispanic community. But she didn't know what the Hispanic housewives on 112th Street and Park wanted any more than you or I would. I don't think she'd ever seen a barrio in her life."

This was a rocky time in Hernandez's personal life. She'd married her fourth husband, Paul Hallingby Jr., a managing director at Bear, Stearns. By several accounts, she felt strongly for him, to the extent of using her network to throw business his way. But her own projects kept consuming her; too many evenings, Hallingby would end up at home talking to Sasha. One day Hernandez came home to find Hallingby gone. She was devastated, and the divorce that followed was a bitter one.

Other women jump from board to board and marriage to marriage without stirring more than the usual talk. But Hernandez has become a controversial character, even to those who don't know her whole story. Fellow board members tend to find her cold and domineering. Not long ago she apparently alienated her colleagues at the Met; she did the same on a recent benefit committee for the Countess of Mountbatten's favorite charity. ''She's a cool person," says one observer. ''Icy," says another. Admirers say it's only that she doesn't suffer fools gladly, and point to her very real boardroom accomplishments—establishing a teen-pregnancy clinic at New York Hospital, for example.

''She does these things because she's full of intellectual energy, not because she's hungry for power," says a friend, Eileen Finletter. ''It's not power for the sake of power; indeed, if she had more tact she'd have more power. She really wants to do things. She's a fighter." Earlier this year, Finletter was asked to help stage a fund-raiser for Children's Express, the organization that helps children to be journalists. ''I was supposed to do the benefit for them, but I really didn't know how to pull it off. So I called Marife, and she made it happen. She was fascinated by Children's Express, even though clearly it wasn't any power base for her. She came in with ideas, with money, and with time. And the benefit happened very much because of her."

Hernandez is less popular with various successful women who have worked with her on different occasions. "I worked with her closely and got to know her well," says one. ''We had several long lunches, exchanged intimate secrets, but when the work was done, it was as if we'd never known each other. Even now I'll see her at charity functions and she doesn't seem to recognize me." Says another, ''When you have something in common with her, she's close to you. And the funny thing is that she's sincere about that. But when you don't, she's not. She turns it off. And I know several women who've been hurt by that, and are bitter about it. I'm not. I've just learned never to count on her as a friend. Now I take her as a social acquaintance, that's all."

Some say that in fact the controversy is a nasty matter of racial prejudice, that some of the upstanding members of the boards on which Hernandez sits are simply old Wasps ruffled by the presence of a Puerto Rican. But at least as many suggest that Hernandez, far from being victimized by her Hispanic heritage, has used it in New York to shrewd advantage. As one prominent woman puts it, ''all those boards needed someone with a Latino name, and she's it. She's New York's resident Puerto Rican."

"Absolutely ridiculous" is Hernandez's indignant response. "On the contrary, being Hispanic has presented difficulties for me many times. On television, I had to really prove myself. As for the chief-of-protocol job, most Hispanics don't get a job like that, they get head of Hispanic affairs.

"Sometimes," she adds, "I think it would be great if my name were Jane and I had blue eyes and blond hair and came from New Jersey. Because it is something I have to keep explaining. I can't tell you at how many dinner parties I have to explain that, yes, I am a citizen. And people look at me and say, 'Are there other white Puerto Ricans like you?' I've turned it into an asset because that's my personality."

There's pride in that reply. And pain. And both feel real. And perhaps it's just an irony of life that the more real they are deep down, the more artifice they sometimes produce.

In Hernandez's case, the further irony is that she doesn't need to embroider the facts. No one particularly cares if a woman has four marriages or five to her name, so why conceal a husband? And her accomplishments are real, so why exaggerate her academic record? And why have a flack like Jurdem to make the hard sell? For all the steely control she exhibits, Hernandez, on a deeper level, may simply lack the confidence of her own credentials.

A few days later, I get a call from Jurdem. He tells me that Hernandez was offered the post of New York cultural affairs commissioner, but turned it down. Really? I ask. "Absolutely, positively," Jurdem replies. Somehow, it doesn't strike me as the kind of job Hernandez would turn down. So I call Diane Coffey, Mayor Koch's chief of staff. Coffey is the one who interviewed all twenty-three candidates and chose a black woman named Mary Campbell for the job. "No," says Coffey, rather puzzled. "Hernandez wasn't offered the job."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now