Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowEDITOR'S LETTER

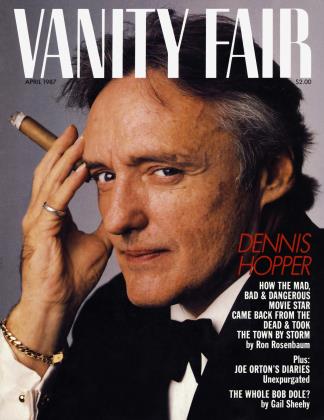

WILD CARDS

Take a good look at our cover boy. What a smug tuxedo. What a prosperous cigar. Only the crazy glint in the eye reveals it's Dennis TTopper, first among fiends. Et's a classic Hollywood comeback. Until his award-winning performance in Blue Velvet last year and the publication of his book of photographs, Out of the Sixties, Hopper's life seemed to be one long lost weekend, a rampaging case history of how far-out you can get and still come back alive. Hopper started dicing with his jinx in his first major film, Rebel Without a Cause, a movie with a doomed cast: James Dean, Sal Mineo, Natalie Wood, who all took one walk too many on the wild side. Hollywood fell out of love with Hopper during a legendary shoot-out with veteran Old Guard director Henry Hathaway, but courted him again after the runaway success of Easy Rider.

Unfortunately, the scramble-eyed hippie he played was an all-too-true expression of Hopper's own zonked psyche. The years that followed were downhill into a hazy purgatory of drug abuse, troilism, and crazed gunslinging in New Mexico. They ended in a straitjacket four years ago. Now, in the cleanup era, Hopper's too hip to be frozen in a flashback. He is one of those totemic actors who get strung out on the Zeitgeist—and make us all feel involved in the outcome. As always, he's moved with the times, repudiating booze and drugs, rededicating himself to his wasted talent. Incredibly, it's still intact. In the extraordinary interview with Ron Rosenbaum on page 76, he tells V.F. what it feels like to be a rebel without a cause thirty years on. And the look in his eye suggests that there may yet be a few surprises in the next reel.

There was no last reel to British playwright Joe Orton's story. At the moment of his greatest promise, when Swinging London was at his feet, he was hammered to death by his lover, Kenneth Halliwell, in their claustrophobic North London room. Halliwell then took an overdose himself. In life they had shared everything except success. For years Orton's diaries were too hot to publish. This month the public can read for themselves the raw material of Orton's inspiration. Our extracts begin on page 98. The diaries deserve to be seen because they reveal so much more than the compulsive sexuality of the playwright. What they give us is the clearest expression of Orton's writing voice—cocky, honest, and killingly funny. Like a knowing Candide, he chronicles his brushes with the chichi world, counterpointing them with a Grand Guignol sex life and the black farce of his emotional relationship with the increasingly alienated Kenneth Halliwell.

Because we know Orton's fate, his mordant descriptions of Halliwell's mounting tension take on a grim context. You don't know whether to laugh or cry.

On page 92 Orton's biographer and diary editor, John Lahr, has written for us a wonderful evocation of the Orton-Halliwell relationship to introduce the diary extracts. It would be too easy to see Halliwell as a nagging drain on his lover's talent. That was not the case. When they met, Orton was a raw kid from the sticks, thirsty for Halliwell's superior education and antisocial wit. They began writing together, and some of Orton's most brilliant titles—Loot and Prick Up Your Ears, the play he never lived to write—were actually invented by Halliwell. But Halliwell was always doomed to be a source. The fact is the talent belonged to Orton, and the plays that fed on this weird relationship catapulted him into the first rank of dramatists. As Lahr points out, he "instinctively taunted the bogus.... Orton's laughter invokes a world of no consolation." Halliwell's tragedy is that of many spouses of the famous. The first Mrs. T. S. Eliot, Zelda Fitzgerald, and Mrs. Thomas Hardy were none of them amused to be a poet's muse. And who can blame them?

You can see Orton come to life this month in a dazzling new movie by Stephen Frears taken from John Lahr's biography of Orton, Prick Up Your Ears. Gary Oldman, whom V.F. featured last year when he played Sid Vicious in the movie Sid & Nancy, must be headed for an Oscar with his uncanny incarnation of Joe.

Our third tough guy in a testosterone-packed issue is Senator Robert Dole, the latest of Gail Sheehy's portraits in power (page 112). As with the George Bush profile, in the February issue, we read fascinating new material that cannot fail to color our assessment of his candidacy. Sheehy explores for the first time the wellspring of Dole's indefatigable drive. On the Italian front in the war, at the peak of his youthful athleticism, Dole lost the use of his right arm. For three years he was hospitalized, and he conquered his disability only through a psychological campaign he wages to this day. Perhaps, Sheehy speculates, the way Bob Dole defied his disability was to choose the hardest possible professional road—politics. And the duel of wits is the only sport he can play. Dole has turned his handicaps into soaring political assets that may take him to the White House itself.

Hopper. Orton. Dole. Three men of our times whose rage for life bums up the pages of April Vanity Fair. Don't Bogart this issue.

Editor in chief

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now