Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowBEING AND SOMETHINGNESS

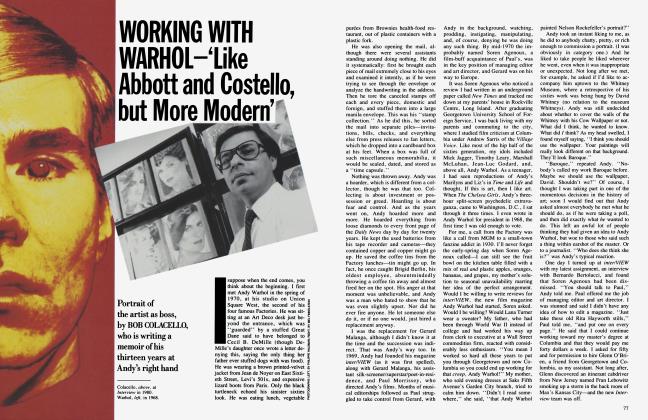

JAMES ATLAS

The big new Sartre biography comes from France, where philosophers are like rock stars

Book Marks

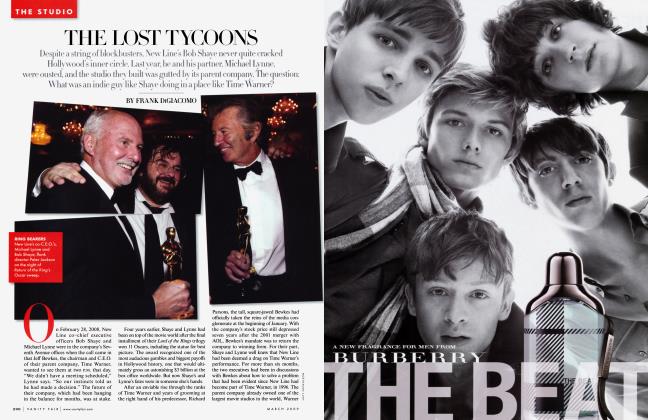

stars." Front-page news in Le Monde and Le Matin, Sartre was on the bestseller list for months. "Une biographie globalissante, " raved the critics, "un travail colossal. ' '

Rights have been sold all over the world: Italy, Finland, Holland, Brazil, Japan. "We have never published a book of this complexity that's been sold to so many countries," says Andre Schiffrin, the managing director of Pantheon, who originated the project.

Six years ago, when Schiffrin approached Cohen-Solal, no French publisher could be persuaded to underwrite a biography of Sartre—not even Sartre's own publisher, Gallimard. In 1980, 50,000 people had followed the great man's coffin through the streets of Paris; by 1981, he was out of fashion, his reputation in decline. Sartre was an Old Leftist; the sixties were dead. As a critic, he was obsolete; his last work, the multivolume study of Flaubert, went largely unread. Sartre was "in purgatory," recalls his biographer. He was passe. Undaunted, Schiffrin pursued the

matter with Cohen-Solal, whose book on Sartre's colleague Paul Nizan he had admired. In a hot, noisy cafe on the Boulevard Raspail in the middle of August, he offered her "whatever she needed to write the book." Cohen-Solal was hesitant. She didn't feel qualified. Sartre was too large a figure; she was more interested in writing a book about women in medieval Algeria. "I was absolutely terrorized," she says. "He was—how do you say?—demesure, beyond measure, out of proportion to everyone else." But Schiffrin was convinced that Cohen-Solal was the right person for the job. She had interviewed Sartre for her book about Nizan; she had worked in publishing and made something of a name for herself as a literary journalist; she was educated, but not an academic. And she had a forceful personality. She was lively, articulate, persuasive. Schiffrin "wanted someone who could make a case for Sartre," says Cohen-Solal, "someone presentable."

Presentable she is. An Algerian-born Jew who grew up in France and studied at the Sorbonne, Annie Cohen-Solal is nearly as celebrated in the Parisian press for her looks as for her literary accomplishments. Leering reviewers dwelled on a publicity photograph of the biographer, "one shoulder amiably bare (never mind that it was winter), sporting a frivolous scarf." The American novelist Jerome Charyn, panting in Liberation over this "sorciere juive algerienne," "un chat au visage spectral," even confessed a desire to "nibble her neck." It is hard not to be impressed by Co-

hen-Solal. Chestnut-haired, with exotic green eyes, she radiates intensity. Arriving for an interview in black stockings, silver bracelets, and a short skirt, she's the epitome of Parisian chic—what the writer in Passion called "beaute-intelligence." Her energy is prodigious. In just four years, she mastered the vast archive of Sartre's work, both published and unpublished; tracked down hundreds of friends and acquaintances in remote provinces of France, in Israel, Italy, America, even the Antilles; buried herself in old newspapers and obscure documents. Determined to reconstruct the naval career of the father, Jean-Baptiste, who died in Sartre's infancy, she unearthed nautical logs of his voyages to the Far East. When she learned that a cache of three thousand letters from the Sartre family had turned up in the shop of a Perigueux antiques dealer and was about to be sold to the University of Texas, she hopped on a plane and spent the night going through them. "I scoured everything. I even examined the box itself. Nothing escaped me."

Not that Sartre was exactly secretive. The testimony scrutinized by his biographer is candid to the point of self-absorption. His autobiography, The Words; the novels that were essentially romans a clef; biographies of Baudelaire and Genet that were as much about Sartre as about his ostensible subjects; and his posthumously published war diaries and letters. Sartre's conversations with Simone de Beauvoir, collected in Adieux, told us more than we needed to know about Sartre's sex life, his distaste for dogs and cats, his ideas about food ("The cooking of a vegetable is the transformation of a given object without consciousness into another object equally devoid of consciousness").

Sartre was a public figure on a scale unimaginable in America; whatever he did was news. If he made a proclamation—about the Algerian war, the role of the Communist Party, a strike of workers at Renault—it was covered on page 1. He traveled the globe, held press conferences, conferred with Mao Zedong, Fidel Castro, Khrushchev. "Everywhere they went," writes Cohen-Solal of Sartre and De Beauvoir, "they left the image of their legendary silhouettes." When Sartre died, Giscard d'Estaing sat alone beside his coffin for an hour.

Cohen-Solal has given us a distinctive portrait of this public Sartre, the hero to generations of radicals around the world, from the New York intellectuals of the 1940s to the student revolutionaries of Paris in May 1968. From my own student days, I can still remember the New Directions edition of Nausea, a small, austere volume that gave off such vivid emanations of Europe, modernism, high culture, and subversive politics.

"I was never really political," says Cohen-Solal. "I was not a rebel, a revolutionary, but I was on the social borderline. As an Algerian Jew, I didn't feel French." Sartre's constituency was workers, intellectuals, the disenfranchised, the oppressed. He wrote for "the youth of the world," declares CohenSolal—the same audience she has in mind. Her narrative is perky, up-to-date, spilling forth in a hectic, breathless rush lashed on by the present tense: "Failures here, successes there. . .On May 27, 1944, No Exit opens at the Theatre du Vieux-Colombier. " It captures Sartre's own intensity, his maniacal ambition, his need to be at the center of things—what Cohen-Solal likes to call his polyvalence. "Everyone has his own Sartre," she says. Hers is the Sartre determined from childhood to be a great man, to impose himself on the world.

Today he doesn't seem a persuasive theorist. For the most part, his "committed" works are polemical, contradictory, even incoherent. He was a "political illiterate," according to a member of the Resistance who knew him during World War II (Sartre managed to stay more or less out of the action, bicycling in the Free Zone with De Beauvoir). His novels and plays seem contrived now, vehicles of theory. Even his philosophy is old-fashioned, with a lot of heavy atmospherics. Cohen-Solal quotes a pas-

sage from Being and Nothingness: "It is certain that the cafe by itself with its patrons, its tables, its booths, its mirrors, its light, its smoky atmosphere, and the sounds of voices, rattling saucers, and footsteps which fill it—the cafe is a fullness of being."

It's this Sartre, the cafe Sartre, who still intrigues us, I suspect. He was the very embodiment of Bohemianism—the writer at his table in some Left Bank brasserie, a notebook in one hand and a cigarette in the other, whiling away the afternoon. For all the torments he suffered, the self-destructive behavior, the drinking and drug abuse chronicled in Cohen-Solal's biography, Sartre did as he pleased. Marriage was bourgeois; fidelity was hypocritical; the family was "a pocketful of merde." Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir had lots of lovers, dined out every night, hung around the Brasserie Lipp and the Flore. "If the local barkeeps had one shred of honesty, Simone de Beauvoir and Sartre should drink for free in all the bistros they put on the map," wrote Boris Vian in his Guide to Saint-Germain-des-Pres. They were existentialism.

Even the word is dated now, but in the postwar years it was emblematic of a way of life. What was existentialism? The freedom to create one's own destiny—a concept reduced by the sixties generation to "Do your own thing." For Sartre, it served to justify his political independence as a left-wing intellectual—and to provide a rationale for his philandering. Sartre maintained that his love for De Beauvoir was "essential," but he still insisted on the necessity of "contingent love affairs." Cohen-Solal chronicles a bewildering succession of amours passionelles—of Olgas and Wandas and Sylvies. There was the Lunar Woman, the wife of a colleague in Berlin; Lena Zonina, his interpreter in Russia; a mysterious Dolores, his lover in New York. There was the student he stole from his friend Maurice Merleau-Ponty, "a very hot chick who sucked my tongue with the strength of a vacuum cleaner." For one who spoke of "the nothingness of the flesh," Sartre got around.

In keeping with his belief in "transparency," or total candor, he discussed these affairs at great length in his letters to De Beauvoir, reviewing his progress with "the little woman from Oran," whose "case" interested them because she was a virgin: "I took off her blouse, she took off her dress and her pants." Guilt was a bourgeois emotion, which didn't prevent Sartre from feeling remorseful now and then: "I deeply and sincerely feel I'm a bastard, and a smalltime operator on top of all that, a kind of scholarly sadist and civil servant Don Juan enough to make you vomit."

In his last years, Sartre became a virtual invalid, disabled by decades of drinking, smoking, speed; groupies brought him forbidden alcohol, hiding the bottles behind his books. Sartre's favorite was Arlette Elkaim, an eighteenyear-old high-school student whom he later adopted. But there were also boys, it seems, or one boy, anyway—a young Oriental Jew from Cairo named Benny Levy, who was Sartre's secretary in the last, decrepit years of his life. Their relationship, speculates Cohen-Solal, was "an escapade." Sartre found in Levy "the ideal friend with whom to indulge a number of illegitimate pleasures to which his other friends had no access."

Sartre: A Life will have some competition. Simon and Schuster has just brought out another big biography, by Ronald Hayman; but Cohen-Solal's book is definitive, and she's promoting it with zeal. Already fluent in Hebrew, Arabic, German, and English, she learned Italian in three months so that she could appear on radio and television when the book came out in Italy. She's been to Canada and South America on its behalf. Sartre has made CohenSolal a celebrity. One day she's in New York giving a lecture at N.Y.U.; the next she's in Paris; the day after that she's in Berlin, moderating a television special on the city's 750th anniversary. "I'm a European intellectual," she says proudly.

For Andre Schiffrin, the worldwide success of Sartre entails a certain pleasing irony. It was his father, Jacques, a French Jew, who founded La Pleiade, the handsome editions of the French classics published by Gallimard that adorn the bookshelves of every literate home. Forced to flee France under the Vichy government, he arrived in New York and started over, founding Pantheon with the German publisher Kurt Wolff. "Without Petain," Schiffrin fils commented wryly to Liberation, describing his pursuit of Cohen-Solal, "this book would no doubt have originated in France." Royalties from the Pleiade continue to enrich the house of Gallimard. But the rights to CohenSolal's biography, which Gallimard declined to sign up six years ago, cost them a million francs.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now