Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowUpdike's Version

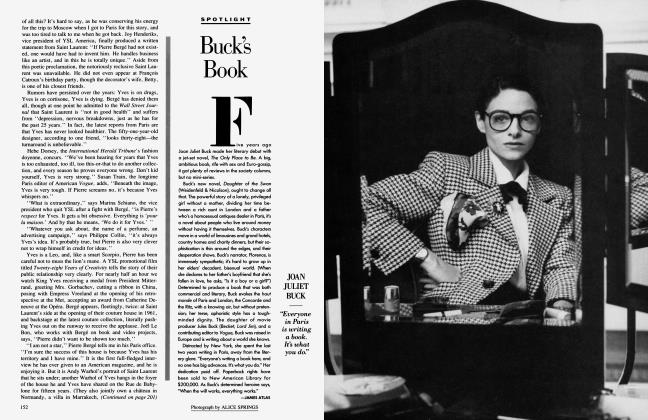

SPOTLIGHT

John Updike is a straight-A student who just happens to write the most vivid prose in America. Since his debut with The Carpentered Hen in 1958, he's made known his intent to write a book a year—and each year a book arrives. Roger's Version, out this month, is stranger even than Bech's or Rabbit's. Updike's world is so distinctive, so utterly his own, that he's coined a word to describe its quality: Updikeness. It's a world that encompasses adulterous dentists, suburban wives, used-car dealers, and golf-obsessed priests—a world so recognizably American that it's impossible not to come across ourselves in some comer of Updike's populous oeuvre.

Roger Lambert, the hero—if that's the right word—of Updike's latest, is a middle-aged divinityschool professor who pines for both God and his nubile niece. He's at the dangerous age when life doesn't quite hold enough in store to ward off despair. "You're a funny guy, Nunc," the niece muses apropos one of Roger's halfhearted passes: "Don't want to fuck, don't want to die." What he wants is to know, and the cosmological lore in these pages is awesome—physics, math, church history, computer science. What made Updike go back to the books? 'The same thing that made savages look up in the sky, I guess," he says in his mild, halting way, as if he'd never really thought about it. Updike clearly did his homework for Version, so thoroughly that he even came up with a flaw in the assignment. "Why does life feel, to us as we experience it, so desperately urgent and so utterly pointless at the same time?" wonders Roger. Updike's reply: "Faith is the only news of God we're going to get."

Invisible or not, He gets a better press than humanity. Updike's protagonists have never had a lot of patience for blacks and Jews and women (and Roger Lambert is no exception). "I'm aware of race," Updike says. "I'm aware of myself as a Wasp who sees himself being drowned by the vitality of these others." Still, his own religion—he's an Episcopalian—has its comforts. "I don't go to church every Sunday, but I go," he says. "It helps me be me." Updikeness personified.

JAMES ATLAS

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now