Sign In to Your Account

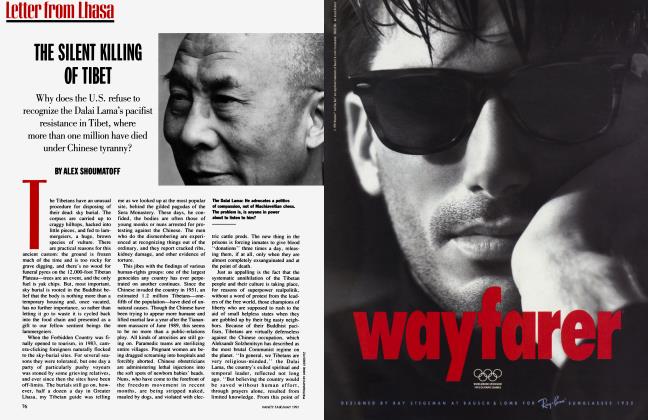

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

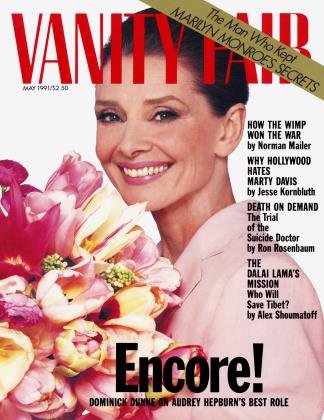

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowTHE PRINCE OF AFTER-DARKNESS

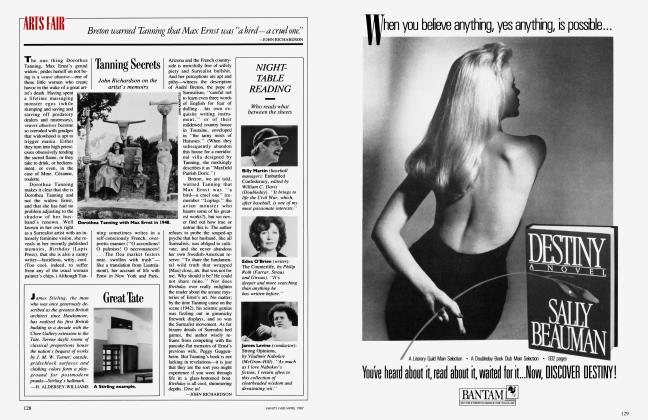

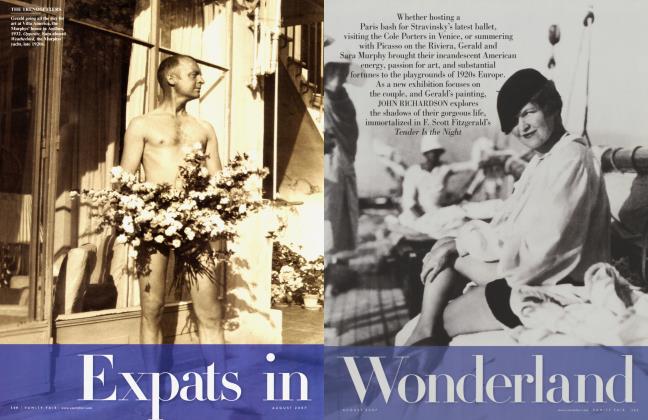

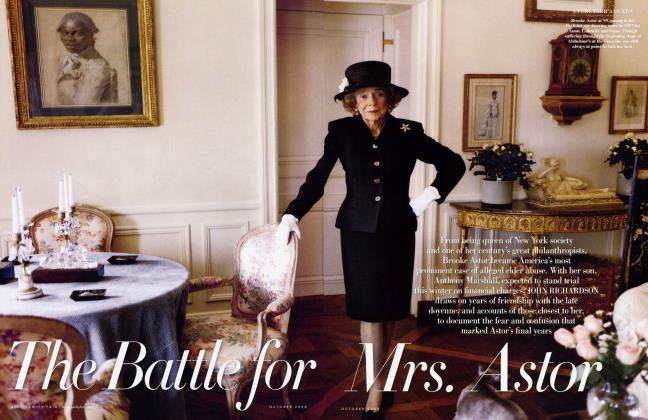

Johannes, Prince of Thurn und Taxis, who died in December, was descended from Mad King Ludwig of Bavaria and lived up to his heritage. In his own way as prodigal as the Kuwaiti emirs, with $2.5 billion and a madcap consort, "Gloria TNT," sometimes Johannes played noblesse oblige—sometimes Caligula. JOHN RICHARDSON reports on Europe's last exemplar of flamboyant royal decadence

JOHN RICHARDSON

Gloria served him a colossal birthday cake with sixty candles shaped like penises.

His Serene Highness Johannes Baptista de Jesus Maria Louis Miguel Friedrich Bonifazius Lamoral, eleventh Prince of Thum und Taxis, who died last December at the age of sixty-four, was the 119th-richest man in the world. And although he was down to a mere six castles, from about a dozen before World War II, he was still Germany's largest landowner. If few members of the nobility eclipsed him in territorial power, none eclipsed him in sheer insolence. People loved to hate Johannes, and by the same token hated to love him if he let them down by behaving well. For his part, Johannes came to take such pride in his reputation for outrageousness that he felt obliged to live up to it. The world expected him to behave like Caligula: very well, he would do so.

Nevertheless, Johannes could be a dependable and genial friend—on his own turf, that is. At his five-hundred-room castle of St. Emmeram at Regensburg— "larger than Buckingham Palace," visitors were told—or Schloss Garatshausen on the Stamberger See, or Schloss Taxis in Swabia (separate buildings for the princely family, the princely guests, the lesser guests, and the now disbanded private army), or his various antler-hung hunting lodges, Johannes was a sardonically amusing host until drink took over and his wayward intelligence would gutter like a candle.

Away from his turf, above all in New York, Johannes was at his most Caligulan. At cafe-society parties, his brew of blue, blue blood, inherited from autocratic Austrian Habsburgs, dotty Bavarian Wittelsbachs, and effete Portuguese Braganzas, would bubble ominously, and, like a vampire exposed to moonlight, Johannes would turn into a monster: a Till Eulenspiegel-like perpetrator of demonic pranks. Or, to take another Richard Strauss character, the buffo Baron Ochs out of Rosenkavalier, with a dash of Wagner's grisly Gibichungs.

Before we confront Johannes the Bad, let us take a look at the noble profile on the other side of the coin, Johannes the Good: the stoic who faced two successive heart transplants with exemplary fortitude; the Knight of Malta who lay in state last Christmas in his private chapel, guarded by 6 of his 170 retainers. His coronet and orders (the coveted Golden Fleece was conspicuous by its absence) were displayed at his feet, and he was garbed in the red gala uniform of the Knights of Malta. The dead man was deeply mourned not just by his immediate family and countless Almanack de Gotha connections but by thousands of employees on his estates (in Brazil and Canada as well as Germany), in his banks and breweries, and by thousands more—townsfolk, farmers, huntsmen, foresters—who lived in his fiefdom. Johannes the Good was adulated, as his great-grandmother's first cousin, mad King Ludwig, had been, for his colorful eccentricities and excesses as much as for his benign paternalism.

Like his faults, Johannes's qualities smacked of another age. His philanthropy, for instance, was not a matter of fiscal contrivance or public relations, as it so often is today, but of feudal tradition. Every day he fed three hundred poor people and students in the vast refectory of St. Emmeram. He was always ready to house scholars who came to study the hundreds of medieval manuscripts, thousands of musical scores, and hundreds of thousands of volumes in his vast baroque library. Johannes was also a most discriminating patron of music. The theater bored him, but he thought it very fiirstlich (princely) of his drama-student wife, Gloria, to put on plays by Friedrich Durrenmatt and Max Frisch in the ballroom. He was vastly amused when she took a leaf out of Marat/Sade—a play he admired because "it was so like a cocktail party"—and set about rehabilitating the local lunatics by having them act in avant-garde productions (no more difficult than training a maid, she said). Johannes was less pleased when Gloria asked Prince, the rock musician, to give a concert in aid of bum victims, who had a special claim on her sympathy. "My ancestors used to have Haydn perform at these functions," he said. "I only wish he were still available. Haydn would never have had the impudence to call himself Prince."

Johannes's courage was greatly to his credit. From childhood onward, he had been openly anti-Nazi, "because the Nazis were so fearfully vulgar," he always claimed, but it was typical of Johannes to put his more creditable feelings in an uncreditable light. His father, Prince Karl August, had done his best to instill in his son a measure of old-fashioned decency. And he succeeded to the extent that the adolescent Johannes made a point of introducing himself and shaking hands with anyone wearing a yellow star. "I only hope my greetings didn't terrify those poor people," Johannes said. The Thum und Taxis family suffered for their anti-Nazi stand. Prince Karl August was sent to a concentration camp, where he shamed the Kommandant into banishing a guard to the front for dishonorably shooting an inmate at point-blank range. (Johannes himself was never incarcerated, as he sometimes liked to claim.) Hitler reserved another fate for Johannes's first cousin Prince Gabriel: like many other heirs to princely families, he and another close relative were sent to almost certain death on the Russian front. When Gabriel was killed at Stalingrad in 1942, Johannes was assured of eventually inheriting the title.

Thereafter, few targets gave Johannes more pleasure than German and Austrian aristocrats who sought to conceal their Nazi affiliations under sanctimonious veils. A principal offender was Prince Otto von Bismarck, whom Johannes delighted in baiting, most memorably at a dinner given by the Windsors. Hypocrisy was the only thing he abhorred more than vulgarity. "Is it true that Himmler declined your advances?" he asked a Pharisaical cousin during a conversational lull at a party.

Johannes took great pride in being a connoisseur of character—bad character. And it is true, as long as he was reasonably sober, he could sniff out pretension and falseness, vanity and fraud, with the pertinacity of a police dog. When he was drunk, however, the innocent, above all anyone within reach of

his back-patting hand, were as much at risk as the guilty. At a ball in Munich, Johannes kept close to a tray of cream puffs so that he could smear them on the shoulders of the more sycophantic guests under cover of giving them jovial Bavarian slaps. When one of his victims came after him, he fled through the kitchen, telling the startled scullions that the

press were in pursuit. Another time, he substituted a razor blade for the cream puffs, to the detriment of many a dinner jacket. His excuse that he picked only on "awful people'' was revealing in that Johannes, like many another alcoholic, was far from blind to his own awfulness. Indeed, his awareness of the monster within was one of the more touching things about him. "Please don't let on how awful I am, ' he begged a friend who had introduced him to a susceptible young man. "He thinks I'm nice."

Besides childish perversity, Johannes's practical jokes exhibited a subversiveness and black humor that smacked of Dadaism. Like the Dadaists, he wanted to deride and defy conventional morality and trigger anarchic situations. He would put as much calculation, fantasy, and nerve into his effects as the late Charles Ludlam put into his absurdist farces: for instance, the ingenious retribution Johannes devised for a New York jeweler who tried to exploit his name. When this man, whom Johannes barely knew, insisted on giving a party for him, he smelled a rat. Sure enough, it transpired that the jeweler's best client—a former bootlegger's former wife —would pay her bills only if she was invited to meet a title or celebrity. She had one other weakness: Mitzi, a toy poodle. On arriving at the party, Johannes lured the dog into the bathroom with a canape and clipped off its pom-poms. He then rejoined the guests, introduced himself to Mitzi's owner, and offered her a lift. Delight turned to dismay when she caught sight of her shorn pet. "Dear lady,'' Johannes said, taking her hand, "not a word until we get into the limousine." As they drove off, he told her that, "as a typical Hun," he had little respect for human life; animals, however, were another matter. "When I caught that loathsome jeweler clipping the fluff off poor little Mitzi..."

In fact, Johannes was anything but "a typical Hun." Although he traveled on a German passport, he always claimed to hate modem Germany. He would remind people that his ancestors came from Bergamo; that his mother was Portuguese, his father half-Austro-Hungarian; and that a great-uncle, whom he somewhat resembled, was that wily old bugger "Foxy" Ferdinand, King of Bulgaria. He sometimes chose to see himself as a latter-day citizen of the Holy Roman Empire, and with some justice. On the strength of the postal service that his family had founded in the fifteenth century, the Holy Roman Emperor had appointed the Thurn und Taxises Hereditary Grand Postmasters, a title of which Johannes was inordinately proud. Hence the postal museum and stupendous stamp collections that attract philatelists to St. Emmeram. Hence, too, Johannes's curiously anachronistic behavior—more in line with the sixteenth than the twentieth century. A case in point is his vengeance (circa 1950) on a moralistic old nurse. It has the ring of a gothic tale. "Flee this castle; there is real evil here,'' the crone had implored one of Johannes's cousins, with whom he was having an affair. The girl rushed to tell the prince, who immediately started rubbing away at a brass doorknob. Why? To generate static electricity. The nurse was duly summoned, and duly shocked. "A sure sign of evil in you,'' Johannes said. "We better try exorcism."

When Goria s1I1

pie, he was not pleased. T

In his feudal way, Johannes could be a most courteous host; he could equally be a most discourteous guest. If cafe society brought out the beast in him, it was because he was socially insecure— surprisingly provincial for all his international airs—and out to avenge himself on his "inferiors" for being impressed by them. "You and I have a lot in common," he confided in a socialite whose tough hide he had a mind to pierce. "Such as...?" she eagerly asked. "Appalling halitosis," he replied, and gave her a squirt of his favorite weapon, Binaca. Intentionally or not, he got her in the eye instead of the mouth. "You swine!" she gasped—to his utter delight. One of the advantages an aristocrat has over a mere gentleman, a friend of Johannes's once observed, is the right to behave like a shit if he feels like it.

The princely puns were almost as painful as the barbs. He made a point of mispronouncing certain names, particularly that of a rapacious old matron whom he enjoyed addressing as "Mrs. Scrotum." "I have nothing against pansies," he told the wife of a South American billionaire, "but I draw the line at shaking hands with 'chimpansies.' " "That's my husband you're pointing at," the poor woman protested, like Margaret Dumont reeling from one of Groucho's sallies. "Then I can only imagine he's very, very rich," Johannes observed. "Why else would a beautiful, wellborn lady throw herself away on a chimpansy?" Another evening, a tipsy California widow Johannes had known for years asked him where he had been born: "Brazil? Poland? Bulgaria? My poor old memory's not what it used to be." "China," he barked, narrowing his fearsome eyes and pulling them up at the corners.

"The trouble with you yentas, you're always whining."

The more birds he could hit with one stone, the better. There was the gala at the Sporting Club in Monte Carlo when he noticed that a group of American women had gone off to dance, leaving their jewel-encrusted minaudieres— "awful, ostentatious baubles," he called them—unattended on a balustrade. Next second, he had pushed them over the edge into a ravine. It was worth it, he said, to watch an aging gigolo risk his neck clambering down to salvage this ' 'Schmuck. ' '

And then there was Johannes the Bad's finest hour, on a plane transporting a load of cafe-society veterans to Persepolis for the Shah's party of the millennium. It was a stormy day. Johannes had armed himself with cartons of Russian salad, which he had spooned into an airsick bag. As soon as the plane began to shudder and buck, he pretended to retch, then set about guzzling the contents of the bag. At the sight of this, a woman across the aisle threw up, whereupon, courteous as ever, Johannes offered her his spoon and suggested that she try some of his and he try some of hers. The imperial plane was soon a vomitorium. As a great friend said, there were times when Johannes conjured up one of those dark-suited ogres by Francis Bacon.

Given his hatred of hypocrisy, Johannes made no bones about liking good-looking boys as much as, if not more than, good-looking girls. In the 1950s, he had a longstanding relationship with a handsome young Chicagoan who was far from poor. ("New money, I fear," Johannes said. "His family did not get to Chicago until after the fire.") Later there was a French boy, whose socially ambitious parents were constantly upgrading their fictitious title, much to the amusement of Johannes. And then in 1979 he dropped in, as he often did, on a Munich milk bar frequented by swinging adolescents—' ' Schicki-Micki ' ' kids— whom he would try to impress by driving up in a Winnebago and claiming to be a Panamanian waterskiing champion. Instead of picking up a boy, he ended up with a twenty-year-old girl, a distant cousin, the half-Hungarian Countess Mariae Gloria Ferdinanda Joachima Josephine Wilhelmine Huberta von Schonburg-Glauchau (more familiarly known as Gloria, and later to the press as "Princess TNT"). Gloria would make a perfect consort, the aging bachelor realized, and provide the solution to a major dynastic problem. Under the terms of his grandfather's will, Johannes was obliged to marry a "katholisches Altesse" (a Catholic highness) and produce an heir; otherwise the family fortune would be divided among the old prince's numerous descendants. This dilemma explains Johannes's exasperated retort, when asked if he would marry his old friend Queen Soraya, a former wife of the Shah: "So likely I'd marry a barren Muslim!"

Marriage to the dynamic drama student does not seem to have changed Johannes's sexual orientation or way of life. Gloria was a free spirit and had no problem adjusting to her husband's proclivities. Each went his or her own way, which did not prevent their producing a longed-for son and heir and two flaxenhaired daughters.

In the course of their honeymoon on board his yacht, L'Aiglon, Johannes could not resist anchoring off the gay beach on the Greek island of Mykonos so as to take his more conventional guests ashore and, if possible, shock them. Hairdressers galore, he promised the ladies. He headed unerringly for the epicenter of the action and immediately set about fomenting a row between two petulant boys. "I saw your friend put sand in your tanning cream," he told one of them. "As for what he did to your towel..." In no time he had fights going all over the beach.

Johannes had chosen well. "Gloria and I have similar roots," he boasted. "My family traces its origin back to Genghis Khan, hers to Attila the Hun." Despite her horror of passing unperceived—barking like a dog on German TV and wearing outrageous witch's hats, pink punk hairdos, and huge, historic diamond rings on each of her ten fingers—Gloria was a good-hearted girl who made the best of her dynastic marriage and took eagerly to motherhood. She wanted at least ten children, she said. Gloria devoted much of her life to giving pleasure: true, to a lot of disco hangers-on, but also to young painters, actors, photographers, writers, pop singers—anyone who had talent, recognized or unrecognized. Despite her noble name, she had grown up poor (her refugee father had once been reduced to washing bodies in a morgue), and now that she was rich, she did what she could for her less fortunate friends. When asked whether she regretted giving up her career as an actress, Gloria said that life with Johannes "turned out to be just like the theater." And indeed the two of them often seemed to have stepped out of the commedia dell'arte.

Like a vampire exposed to moonlight, Johannes would turn into a monster.

In the first years of marriage, Johannes drank less and picked fewer quarrels. However, his wife's obsession with the limelight and exhibitionistic stunts soon began to irritate him. He accused her of being a frustrated actress. When she set about shocking people, he was even less pleased. That was his role. He made this very clear in the course of his sixtieth-birthday celebrations in 1986. In front of a mob of German princelings, Arab sheikhs, and cafe-society luminaries, Gloria serenaded him with a rock ballad she had composed, and then served him up a colossal birthday cake emblazoned with sixty candles shaped like penises. Johannes gave the ithyphallic torte a look of icy dismissal.

Apart from this one lapse, the birthday celebrations constituted as much of an apotheosis for her as for him. I was disinclined to attend a party I knew I would condemn, disinclined to enjoy the spectacle of a million dollars being wasted on the sort of Eurotrash that Johannes supposedly held in contempt. Priggish of me, friends said. Why deny myself the spectacle of the grand finale, a fancy-dress ball with the courtyard full of retainers in eighteenth-century costume doing picturesque peasant chores; the Hall of Muskets festooned with garlands of sausages; the diningroom tables groaning with gold plate (nowhere near as magnificent as the Queen of England's, for all Johannes's boasting); and the ballroom transformed into an opera house for star-studded highlights from Don Giovannil We would never see such extravagance again, I was told, or such decadence: the Khashoggi women, whose panniers were the size of dromedaries' humps; the effete Kuwaiti prince whose square-cut diamond was bigger than any of the ladies'; some of the younger guests, whose dix-huitieme costumes concealed industrial quantities of white powder, seducing the footmen in the conservatory.

Gloria, needless to say, outshone everyone in a two-foot-tall wig, topped with Marie Antoinette's tiara, and a gigantic crinoline looped with ropes of pearls and rivieres of diamonds from Johannes's Ali Baba safes. Later she was lowered from a gilded cloud to belt out a birthday ditty in the Dietrich manner. Her demonic husband let his reputation down by behaving impeccably.

Johannes and Gloria were forever upstaging each other, forever squabbling—sometimes quite violently. "I wish you'd wash your hands before hitting me," Gloria once complained. "I'll never be able to wear that dress again." But in the last resort they were a perfect match—a folie a deux if ever there was one. "Oh, Johannes," she was overheard to murmur into his ear, "I love you. I'd like to cut your throat and drink your blood." And even when she called him Goldie, because of all the gold he wore, or, on occasion, "my old queen," she did so with touching, if twisted, affection. No question about it, Gloria adored her Goldie.

A year or so before Johannes died, Gloria had been obliged to come down off her gilded cloud and help salvage his rickety financial empire. In little more than a year (1989-90), the family holdings are said to have shrunk in value from almost $2.5 billion to something over $1 billion. Ill-health seems to have dulled Johannes's vaunted financial acumen. Advisers reportedly made a succession of unwise investments, including the purchase of a major interest in Butcher and Company, a troubled Philadelphia brokerage house. Recession did the rest. Johannes finally threw out the team that had been managing things and brought in a brilliant lawyer. Meanwhile, Gloria abandoned her electric guitar for a computer and took to studying business methods, corporate law, and estate management to such good effect that Manager Magazin, a leading German financial journal, hailed her as one of the country's most astute businesswomen. Gloria also profited from the experience that her equally rich and even brainier sister, Maya (a qualified lawyer), had gained from her marriage to Mick Flick—one of two playboy brothers who had inherited a substantial interest in the Mercedes-Benz business. Like Johannes, the Flicks had recently been forced to reorganize their finances.

When Johannes died last December, the family fortune was still subject to the terms of the grandfather's will, which favors primogeniture at the expense of the women of the family— Gloria and her two daughters. Virtually everything goes to the son and heir, seven-year-old Prince Albert, a lively child who is supposed to have tried to brain Princess Di's son Harry, his distant cousin, with a toy truck. Gloria is said to have a life interest in around $40 million (less than 5 percent of the huge estate) as long as she does not remarry. However, Johannes, whose extravagance of character did not preclude a thrifty streak, is known to have accumulated a considerable private fortune over the years. Some of this will presumably go to the wife and daughters.

How much control Gloria will have over her son's money is a moot point. Who knows whether the castles will continue to be kept up with time-honored ritual and splendor; whether the poor will continue to be fed in the echoing refectory; whether the clients of the Thum und Taxis bank (whose main branch had its counters sprinkled with holy water on opening day) will continue to have their deposits personally guaranteed by the prince? One thing is certain: the memories of the friends and relations who spent three moving but freezing hours at the funeral will continue to reverberate with Gloria's cri de coeur in front of her husband's catafalque: "Dear Lord, have mercy on the soul of my beloved Johannes."

View Full Issue

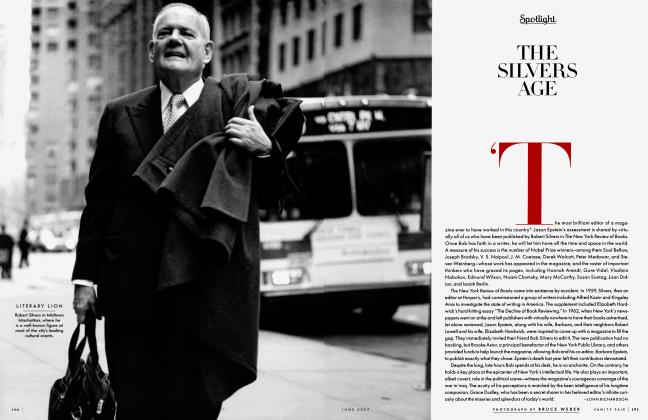

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now