Sign In to Your Account

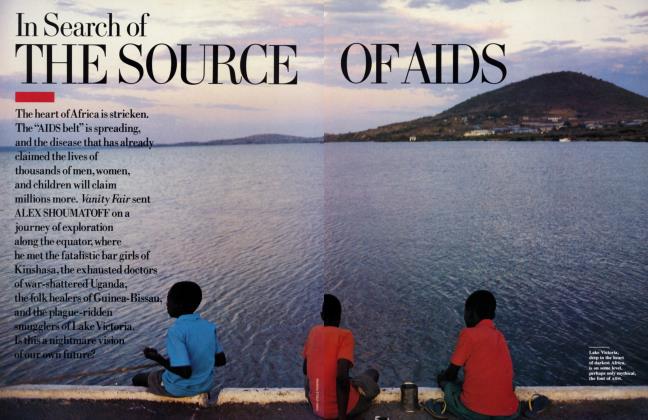

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

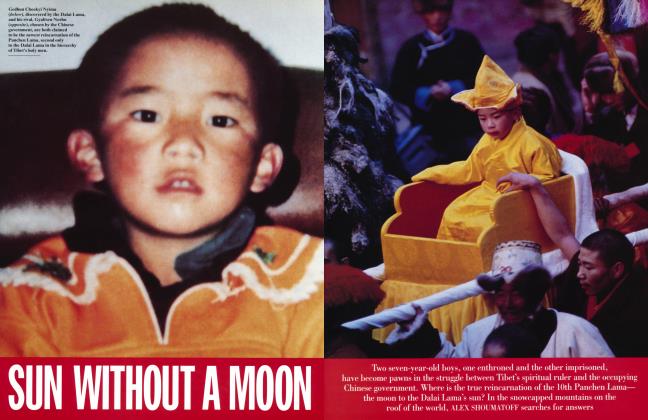

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowTHE SILENT KILLING OF TIBET

Why does the U.S. refuse to recognize the Dalai Lama's pacifist resistance in Tibet, where more than one million have died under Chinese tyranny?

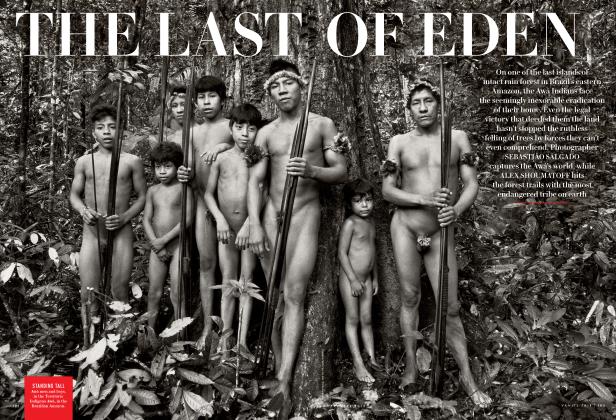

ALEX SHOUMATOFF

Lener from Lhasa

The Tibetans have an unusual procedure for disposing of their dead: sky burial. The corpses are carried up to craggy hilltops, hacked into little pieces, and fed to 1ammergeiers, a huge, brown species of vulture. There are practical reasons for this ancient custom: the ground is frozen much of the time and is too rocky for grave digging, and there's no wood for funeral pyres on the 12,000-foot Tibetan Plateau—trees are an event, and the only fuel is yak chips. But, most important, sky burial is rooted in the Buddhist belief that the body is nothing more than a temporary housing and, once vacated, has no further importance, so rather than letting it go to waste it is cycled back into the food chain and presented as a gift to our fellow sentient beings the lammergeiers.

When the Forbidden Country was finally opened to tourism, in 1983, camera-clicking foreigners naturally flocked to the sky-burial sites. For several seasons they were tolerated, but one day a party of particularly pushy voyeurs was stoned by some grieving relatives, and ever since then the sites have been off-limits. The burials still go on, however, half a dozen a day in Greater Lhasa, my Tibetan guide was telling

me as we looked up at the most popular site, behind the gilded pagodas of the Sera Monastery. These days, he confided, the bodies are often those of young monks or nuns arrested for protesting against the Chinese. The men who do the dismembering are experienced at recognizing things out of the ordinary, and they report cracked ribs, kidney damage, and other evidence of torture.

This jibes with the findings of various human-rights groups: one of the largest genocides any country has ever perpetrated on another continues. Since the Chinese invaded the country in 1951, an estimated 1.2 million Tibetans—onefifth of the population—have died of unnatural causes. Though the Chinese have been trying to appear more humane and lifted martial law a year after the Tiananmen massacre of June 1989, this seems to be no more than a public-relations ploy. All kinds of atrocities are still going on. Paramedic teams are sterilizing entire villages. Pregnant women are being dragged screaming into hospitals and forcibly aborted. Chinese obstetricians are administering lethal injections into the soft spots of newborn babies' heads. Nuns, who have come to the forefront of the freedom movement in recent months, are being stripped naked, mauled by dogs, and violated with elec-

trie cattle prods. The new thing in the prisons is forcing inmates to give blood "donations" three times a day, releasing them, if at all, only when they are almost completely exsanguinated and at the point of death.

Just as appalling is the fact that the systematic annihilation of the Tibetan people and their culture is taking place, for reasons of superpower realpolitik, without a word of protest from the leaders of the free world, those champions of liberty who are supposed to rush to the aid of small helpless states when they are gobbled up by their big nasty neighbors. Because of their Buddhist pacifism, Tibetans are virtually defenseless against the Chinese occupation, which Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn has described as the most brutal Communist regime on the planet. "In general, we Tibetans are very religious-minded," the Dalai Lama, the country's exiled spiritual and temporal leader, reflected not long ago. "But believing the country would be saved without human effort, through prayers alone, resulted from limited knowledge. From this point of view, religious sentiment actually became an obstacle."

CIRCUMAMBULATING

Every Tibetan wants, more than anything, to go to Lhasa, the capital of this vast, spectacular land hidden behind the Himalayas, a third the size of China; to see the Potala, the sumptuous 1,200-room palace where the fifth through the present Dalai Lamas lived; and to circumambulate the Jokhang, the great central temple in the city's heart, built by Songsten Gampo, the seventh-century king who adopted Buddhism. In the early eighties the Chinese lifted their ban on public worship in Tibet.

But they had no idea that the religion was still so strong, that virtually 100 percent of the population was still nangpa, "within the faith," and continued to revere the Dalai Lama as the fourteenth incarnation of their ruling archangel even though he had been driven out of the country in 1959 and none of the younger generation had ever set eyes on him. It was he who held together what was left of the Tibetan identity here and abroad, and a pageant of pent-up devotion, the likes of which had not been seen in the West since the days of Chaucer, soon reclaimed the land.

A decade later, the whole population seems to be on a pilgrimage. Wherever there's a shrine or a holy place to be circumambulated, a ring of Tibetans is usually shuffling around it, murmuring mantras, twirling prayer wheels, generating good Karma for their next incarnation. The monasteries are full of long, swaying, softly humming conga lines of true believers, their awestruck faces illuminated by blazing rows of yak-butter lamps as they make their way from room to room full of gaudy Buddhist art. Many are tall, red-cheeked, ready-smiling members of the Khampa tribe, from eastern Tibet. The women are decked out in massive turquoise and red coral jewelry and red-tasseled braids. The men wear long black robes, with silver daggers and charm boxes on their belts, and both sexes sport pastel-colored high sneakers from the People's Republic of China, to which they are supposed to belong. They have been on the road for days, weeks, months. Some have prostrated the whole way, measuring the tarmac like inchworms: moving their hands, pressed together in prayer on top of their head, down to their throat, to their heart, then dropping to their knees and keeling forward so that every part of their body embraces the sacred earth, then getting up, spitting out the dust, striding forward a body length, and repeating the process.

The inner circuit of the Jokhang is known as the Barkhor and takes about twenty minutes to perform, if you keep moving. But there are many distractions, for the Barkhor is also the liveliest

Tibetan Buddhism has tremendous entertainment value. As a lama in Kathmandu put it, it is the Disneyland of religions.

bazaar, the Times Square of Tibet, and the center of national life, swarming with all kinds of people. Pickpockets, street kids, and pretty girls done up in turquoise and coral mingle in the slowly turning throng of devotees with pale, edgy, baby-faced Chinese soldiers and gyan-vi—plainclothes operatives of the dread Chinese Public Security Bureau posing as beggars or itinerant monks (you can tell who they are because they wear shades and periodically raise side bags containing walkie-talkies to their ears).

If anything is going to happen, if there is to be another outburst of reactionary counter-revolutionary secessionism, it will probably be here, in the Barkhor. Like the flare-up of September 1987, in which twenty-one young circumambulating monks suddenly raised the outlawed Tibetan flag (two snow lions against snow peaks) and began chanting for independence. A few days later, an angry crowd stormed the police station where the monks were being held and set it on fire. Or the riot in March of the following year, in which three Chinese policemen were stoned to death, and four Tibetans, one of them a fifteenyear-old monk, were gunned down—after which Beijing's policy of "merciless repression" was imposed. Or the demonstrations in May 1989, which resulted in the deaths of 16 or 800 Tibetans (depending on which side's tally you subscribe to).

My new friend Jules, with whom I was circumambulating the Barkhor one afternoon not long ago, motioned with his eyebrows up to a rooftop where two Chinese soldiers were standing in front of a mounted high-caliber machine gun and surveying the crowd. Jules was an antiques smuggler who specialized in Ming porcelain. We had flown to Lhasa together from Kathmandu, Nepal. I had come in squeaky-clean—no Dalai Lama pictures, nothing to suggest, with my binoculars and field guides to the birds, butterflies, and wildflowers of the Himalayas, that I was anything other than who I said I was: a naturalist. But Jules was playing a more dangerous game. He had gotten a sixty-day visa for China, booked a flight to Ch'eng-tu, the capital of neighboring Szechwan, and simply gotten off at Lhasa. When the P.S.B. officer at the airport asked for his Tibetan travel permit, he produced the visa and said ingenuously that he thought this was part of China. "At first the guy said I'd have to stay at the airport and take the next flight out," Jules was telling me. "But after several glasses of cognac and a ten-dollar bill slipped discreetly into his jacket pocket, he started to tell me the story of his life. There was an electric cattle prod on the table between us, the kind the P.S.B. routinely uses for interrogation. I picked it up and asked, 'What's this thing?'

" 'A shock,' he said.

" 'Did you ever try it on yourself? See what it feels like?' I jabbed it at him and he shrank back in terror. The next morning he put me in a car to Lhasa."

Being the only inji, as Westerners are known in Tibetan (from "Englishman"), in sight, we were objects of wide-eyed curiosity, particularly from some Golok nomads who had blown in from a vast, practically uninhabited prairie the size of Colorado known as the Changthang, "the northern grassy solitudes." Three women danced around us holding up turquoise-and-coral necklaces, earrings, and amulets, and asking cheerily, "Hello how much? Come on. Your last how much?" One of them pinched me encouragingly on the butt. "You too much," I told her.

You wouldn't have guessed from the high spirits of the Tibetans what they have been through, or that they are living in a very ugly police state. Everything seems calm in the Barkhor, even festive. A group of Hor nomad girls were gaily spinning a row of cylindrical bronze prayer wheels along the wall of the shrine with the absorption of teenagers in a video parlor. Tibetan Buddhism has tremendous entertainment value. As a lama in Kathmandu put it, it is the Disneyland of religions.

The faces of these people are extraordinary—so different from the pallid masks that the Chinese soldiers wear. When Tibetans smile, their eyes widen, the skin draws back, and their whole face expands and lights up like a bulb. Contentment and untroubled clarity radiate from their features, maybe because of their practice of the system for overcoming the suffering of existence that a Hindu prince named Siddhartha worked out 2,500 years ago after years of ascetic ordeals, finally becoming a Buddha, or enlightened being. In the 1,200 years since the system reached Tibet it has been refined in monasteries that produced their own Einsteins and Freuds, who did their research on inner science, tearing consciousness apart and scrutinizing it under clinical conditions. One Western practitioner describes the set of specific meditations and visualizations that compose Tibetan Buddhism as "not so much a religion as a completely down-to-earth and practical science of mind. The Tibetans deal with the mind in a very profound way. They are masters of onepointedness and interiorization, and until you get the mind sorted out you can't get anywhere in your spiritual practice."

But one of the main teachings of the Buddha is that outward appearances are illusory, and so it is possible that the people in the Barkhor, outwardly all smiles and laughter, are seething inside, that what the circumambulators are chanting under their breath is not the famous core mantra, Om Mane Padme Hum ("The Jewel in the Lotus"), but actually "Chinese, Go Home," and that this whole overpowering pageant of devotion, which seems to be the only thing happening in Tibet, is actually a subtle kind of nonviolent mass protest, and underneath the apparent calm is a volcano.

We pass a distinguished-looking old man wearing a lapel button that reads, to our amazement, l LOVE TIBET. FREE TIBET. I ask Rinchen, the hip young exile from the tour company who came in with me to see everything goes smoothly, to drop back and discreetly get the man's views. A few minutes later, Rinchen catches up with us. "I asked the old man how the situation was and he said it's like being a dog that is taken around everywhere on a leash. You can't bring out your sorrow. Smoke can't come out your nostrils no matter how big the fire is in your heart."

THE EMPIRE STRIKES BACK

In front of the Jokhang Temple is a stone monument commemorating a treaty concluded between Tibet and China in 821-22 A.D. , in which both parties agreed to stay for the next 10,000 years in their respective countries: "Tibetans shall be

Tibetan children were forced to shoot their parents, disciples their teachers, and nuns to copulate publicly with monks.

happy in the land of Tibet, and Chinese shall be happy in the land of China."

But it didn't work out that way. There are two widely divergent versions of what happened in the subsequent millennium, of the complex saga of Sino-Tibetan relations. Some blame the fifth Dalai Lama— the Great Fifth, who built the Potala—for renewing the dormant patron-priest relationship with Beijing established in the days of Kublai Khan, and thus placing Tibet under Chinese suzerainty.

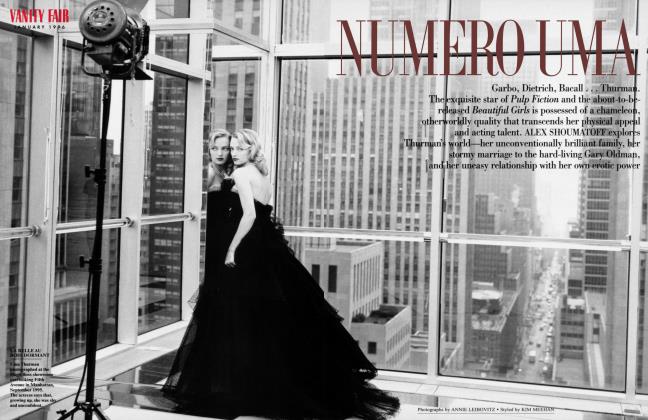

Robert Thurman, a professor of IndoTibetan studies at Columbia University, has a different take. Thurman was the first American to be ordained as a Tibetan monk. He later derobed ("I realized the monk trip was really self-indulgent on my part and I should try to hack it in the world") and married a Swedish high-fashion model. Their second child, Uma, is the sultry star of Henry & June.

"Central Asia was one of the world's great warlord breeding grounds," Thurman explained. "It spawned many of the world's conquering empires—the Tibetan empire of the first millennium; the Mongols, whose empire was the biggest in world history; the Ottomans, who were descended from the Uighurs of East Turkestan, immediately to the north of Tibet. So the lamas of Tibet were quite aware of the military nature of nations.

"In the seventeenth century," Thurman went on, "the Oirat Mongols, who were 20 million strong, spread to the Black Sea, and they tried to win the Great Fifth to their vision of a PanTibetan-Mongolian bloc that would stand up to the Manchus, who were taking over China. But the Fifth realized that a Mongol alliance would keep Tibet in the medieval pattern of a highly militaristic feudal nobility and a monastic elite, and he didn't want that, so he asked the farthest-away guy, who almost never came to Tibet, for a loose hegemony: let the Manchus keep the peace in central Asia. In so doing he bought Tibet three centuries to practice the dharma undisturbed, and Tibet developed from a normally ethnocentric, warlike, imperialistic national culture to a universally Buddhicized, spiritual, peaceful culture.

Tibet evolved a unique personality constellation which I call 'inner modernity'—as advanced as the West is in 'outer modernity,' as extremely inward as we are outward.

"The Fifth in fact created an extraordinary social experiment: a state with zero pollution, zero population growth due to the voluntary celibacy of 20 percent of the males, no military budget, and a completely harmonious relationship with its wildlife, its environment, and its neighbors. Isn't that what we're all looking for?"

But wasn't Tibet pollution-free because it was pre-industrial? I asked.

"On the contrary," Thurman countered, "it was an industrial society. The monasteries were factories, streamlined assembly lines for the most important product there can be—enlightened beings. But the only problem," Thurman conceded, "was that the Great Fifth also set things in motion for a society that couldn't defend itself. Whether he foresaw the destruction of the Buddhist state, whether he intended for Tibet to self-destruct—who knows? Who can know what goes on in the mind of an enlightened being?

"But the most important point in this discussion," he stressed, "is that in all the centuries that the Chinese claimed Tibet as part of their empire they were never there! China's claim was never more than a court fantasy. There is no documentary evidence to support it, while the documentary evidence that Tibet governed itself as an independent entity is extensive. It was like a delegation coming to Beijing from thousands of miles away and saying, We bring you England."

The first serious attempt to take possession of Tibet didn't happen until 1910, when an army sent by the Manchus took Lhasa, committing atrocities that now seem like a dress rehearsal for the current occupation. But a year later the Manchus were overthrown by the Nationalists, and Tibet was left more or less to itself until 1948, when the civil war in China ended with the Nationalists departing the mainland.

There were three things Mao Tsedung wanted badly: Taiwan, Korea, and Tibet. All he got was Tibet. In 1950, he sent an army to "liberate the oppressed and exploited Tibetans and reunite them with the great motherland," and also to protect them from the "forces of imperialism," which was a bit of a crock as there were only ten inji in the whole country and what was he doing there if not committing a blatant act of imperialism himself?

The general population responded to the threat with feverish prayer and circumambulation. The Dalai Lama, who was only fourteen, fled to the Indian border, taking with him more than a thousand pack animals laden with treasure. But a few months later he was persuaded by his spiritual advisers, including the state oracle (who goes into a trance whenever an important decision has to be made), to return to Lhasa and try to work something out with Mao. The two leaders didn't meet until 1954.

The Dalai Lama had seen the possibilities for a synthesis between Buddhism and Marxism, but ended up deciding that Mao was "an enemy of the dharma."

When he returned to Lhasa, the Dalai Lama found that the liberation had taken an ugly turn. The Chinese army and Tibetan riffraff they had recruited were relieving people of their arms, livestock, and other possessions. Everything was being collectivized. Prominent families were being bound and dragged to the village squares for thamzing, or "struggle sessions," and were being forced to confess to their "crimes against the people," and those whose performance was unsatisfactory were being executed on the spot. The Khampa went on the warpath, and the Dalai Lama, who wanted to emulate Gandhi's nonviolence, despaired. He had lost control of the country.

In 1959 there was a major insurrection in Lhasa. Tens of thousands of Tibetans surrounded the Norbulingka Palace to

protect the Dalai Lama from the Chinese, whose program was now clear. Their commander had invited him to a soiree at the barracks. Perhaps they would fox-trot to Bing Crosby records, which was the rage with Lhasa's smart set. But he was to come alone, without his guards. Under the cover of night and in disguise, the Dalai Lama and his family fled south again, the People's Liberation Army hot on their heels, and he barely made it across the Indian border. A hundred thousand Tibetans, including the cream of so-

The new policy was: If you start clamoring for Tibetan independence, you will be cracked down on severely.

ciety and the Lamaist hierarchy, followed, and at least 87,000 of those who stayed behind were slaughtered.

Three months later, in India, the Dalai Lama gave his first press conference, in which he claimed that China's true aim was "the extermination of the religion and culture and even the absorption of the Tibetan race."

The atrocities, which began in 1957, reached a peak during the Cultural Revolution years, from 1966 to 1977. Entire villages were obliterated, their residents crucified or disemboweled, burned or boiled alive, or dragged from the backs of horses. Children were forced to shoot their parents, disciples their teachers, nuns to copulate publicly with monks and to desecrate sacred images. All but 40 of the country's 6,254 monasteries were gutted, and their treasure—$80 billion worth of ancient thankas and gold and silver—was shipped back in endless truck convoys to the motherland, where

it made its way through Hong Kong to European auction houses and private collectors. Thousands of bundles of woodblock-printed scripture—1,200 years of research on the inner workings of the mind—were burned. In the monasteries that weren't razed, huge portraits of Chairman Mao, looking like Big Brother, were put up. Tens of thousands of Tibetans were marched off to a growing string of labor camps in the North, South, and East that made the Gulag look like Playland. Inmates were reduced to fighting over the maggots in each other's excrement. Only hundreds survived. Their appalling conditions are chronicled in John Avedon's powerful book, In Exile from the Land of Snows.

There are incredible stories from this period: high tulkus (recognized incarnations of "perfectionstage adepts," who, in theory, can choose the time, place, and womb of their rebirth) under torture stopping to inhale and shooting their consciousness out of their body and into their next manifestation. Avedon focuses on the ordeal of Tenzin Choedrak, now the Dalai Lama's senior physician, who survived twenty years in prison and labor camps by murmuring millions of mantras and practicing advanced tum-mo heat-generating meditation, which helped him stay alive in his freezing cell and break down the barely digestible fare.

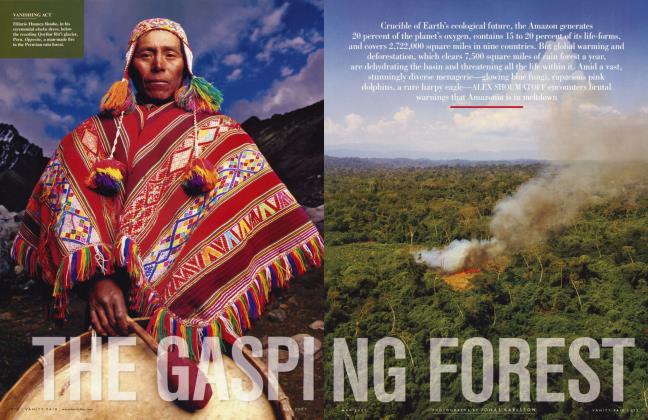

At the same time, there was an all-out onslaught on every other form of life in the country. Untold millions of sentient beings were liberated from their temporary consciousness housings. Cats, caged birds, and lovable golden Lhasa Apsos were exterminated for being parasites and undesirable relics of past society. Songbirds were shot out of trees, the excuse being that they destroyed crops, but actually because they are a Chinese delicacy. By all accounts, the wild animals in Tibet, having never been molested, had been incredibly tame and approachable. Now huge flocks of Brahminy ducks, bar-headed geese, and black-necked cranes (of which only a few hundred are left), herds of kiang (wild ass), drong (wild yak), antelope, gazelle, and blue sheep were machinegunned and cooked up by the occupying forces. The vast virgin forests of eastern Tibet were clear-cut and an estimated $54 billion worth of pine, rhododendron, larch, and oak was added to the endless stream of trucks. The entire subcontinent is still shuddering from the ecological repercussions of this massive deforestation—including floods in Bangladesh and alteration of the monsoons.

One wonders how much of Mao's liberation was motivated by simple covetousness. The name the Chinese gave to their newly annexed territory—Xizang—is telling: it means "Our Western Treasure-House."

It had fertile farmland in the East and South, uranium, lithium, tungsten, borax, and gold, more than ninety totally unexploited resources, strategic importance—whoever controlled the Tibetan Plateau looked down on the rest of Asia—and above all, for the billionplus Han masses, space.

With the death of Chou En-lai in 1976, the oppression in Tibet eased up a bit. Some Chinese began to realize that horrible mistakes had been made in the way Tibet had been treated. By the early eighties it became clear that Beijing was not going to break the back of Tibetan culture. The Old Guard had all died and the cultural lobotomy was aborted. The new policy was: You can have your religion, you can have your dogs (there was a tremendous resurgence of canines, though not the Lhasa Apsos—Nepalese strays, pariah dogs, which have become a real problem around the monasteries). We won't bother you too much, but we won't give you decent jobs or an education either. As long as you accept your degraded status everything will be fine, but if you demonstrate, if you start clamoring for Tibetan independence, you will be cracked down on severely.

But the genocide of the Tibetans by absorption continued. Han Chinese were given generous incentives to settle in Xizang and were rewarded for marrying Tibetan women. Currently, the Han-Tibetan ratio on the plateau is estimated to be 7.5 million to 6 million.

HAPPY HAPPY HAPPY

The Lhasa Holiday Inn is a multimillion-dollar extravaganza the Chinese have sunk into Tibetan tourism, and it dominates the sterile, creepily /984-like Chinese new town that has taken over much of the Happy River Valley, where Lhasa used to be. Tourism is about the only money-making proposition that the Chinese have going in Xizang, which puts the tourist in an awkward position because he is in effect subsidizing the oppression. On the other hand, tourists joined the demonstrations of the late eighties and can be credited with arousing in the Tibetans bourgeois capitalist cravings for things like self-determination and individual rights.

So far, the tourists have not arrived in

The Lhasa Holiday Inn has to be one of the most remote and surreal bastions of modernity in the hemisphere.

great enough number to undermine the culture, to turn the pageant of devotion into a replica of itself, as eventually happens (look at Carnival in Rio, for instance). They are still outnumbered hundreds to one in the conga lines at the monasteries. Besides Jules and me there were a group of elderly Americans, gutsy widows who had taken it into their heads to see Tibet before they die, a German group (Tibet is the sort of place Germans go for—Hitler believed the masters of the universe, the old arcane sages, lived here), a young Brazilian named Marcos who was traveling around the world, and a couple of people like me and Jules, whose presentations didn't quite add up, among them a French diplomat who was right out of Casablanca, smoking coolly and traveling on a regular passport as a "manager."

The Lhasa Holiday Inn has to be one of the most remote and surreal bastions of modernity in the hemisphere, if not the sphere. But Tibet as a touristic experience—the monasteries choked with pilgrims, the dust-, glare-, and altitudeheightened Chaucerian time warp—was so intense and out of this world that I found myself feeling almost grateful for the amenities the hotel offered. It was a lifeline for the discombobulated inji, with its hot running water, nightly videos—Perry Mason reruns, James Bond, One Flew over the Cuckoo's Nest—on the TV, Coke (which had beaten Pepsi to the plateau but was no more the Real Thing than the local version of Kent cigarettes). Something had also been lost in translation in the arrangements of Beethoven's Ninth and "Home on the Range" that emanated incessantly from overhead speakers: they sounded exactly the same. The Han Chinese who tried to run the place up to American standards all looked the same. They were nonindividuated, programmed porcelain dolls, like the girl who greeted me with a mechanical smile and the words "Coupon, please" at the dining-room door, and the younger set at the disco: a dozen girls dancing in formation like aerobics class, soldiers in uniform box-stepping together to hot numbers like Rick Dees's 1976 novelty hit, "Disco Duck." Marcos had the perfect word for the scene: ' 'massificado, ' ' mentally massified. Happy music gushing all day long on the banks of the Happy River, happy bees going about their little tasks, each contributing to the good of the hive, happy tourists, happy Tibetans, happy Han Chinese, everybody playing his part in the wary charade that life in Lhasa had become.

At night Rinchen and I would sneak out of the hotel and, tying on the white gauze masks that everyone wore because of the dust, we would flag down a bicycle rickshaw, and be pedaled past undifferentiated concrete apartment blocks, barracks, and office buildings, all in the same sterile party architecture, to the Tibetan quarter on the other side of town, where the Barkhor was, where the action, such as it was, was. There, in dark little dives straight out of Indiana Jones, we would hear that things were not so great after all.

One time we were led down the dark, rickety, second-story walkway of an ancient, tilting building and seated on a hokey sofa in a low-ceilinged, dirtfloored living room. As the handsome daughter of the house poured us cup after cup of salty, rancid yak-butter tea (definitely an acquired taste), we were told that Tibetans were becoming outcasts, second-class citizens in their own land, like Native Americans or Australian aborigines. It was very hard for a Tibetan to proceed beyond high school because everything at the college level was taught in Mandarin. So there were the beginnings of a hang-out problem. No drugs or prostitution yet, but mahjongg had sifted down to the masses (in the old Tibet, noblemen had gone on mah-jongg binges that lasted for days), and the young blades were playing bilHards, smoking, and sometimes stealing to get along. The Chinese were making cheap radish liquor and rice booze available, perhaps in a deliberate effort to addict young Tibetans, as we did our Indians. It was also Chinese policy to encourage inter-Tibetan violence. Pickpockets and robbers were given lenient prison terms—half weren't even sentenced. Truly disruptive elements were recruited as gyan-yi—"undressed police"—by the P.S.B.

We know the young monks and nuns are for the Dalai Lama and Tibetan independence, I told the man of the house, but what about the others?

"There's no difference between the monks and the laity," he answered. "All have the same feeling."

But later in the evening, he said, "Sixty percent believe in freedom, 20 percent don't care, and 20 percent—those who play footsie with the Chinese—don't want it."

And how will Tibet gain its freedom, with the Dalai Lama ruling out violence?

Pause. Rinchen translates: "He believes it's not possible. Only if China falls apart again, as it did when the Manchus were overthrown in 1911."

KATHMANDU

One afternoon in Kathmandu I rode out to a transit camp for newly arrived Tibetan refugees on the back of a motorcycle with a young exile active in the freedom movement. I'll call him Sonam. Kathmandu has a thriving Tibetan community with a dozen-odd monasteries and several remarkable tulkus. A lot of Tibetans were coming over the border, Sonam told me, to attend a highlevel teaching called the Kalachakra initiation, which the Dalai Lama was giving the following month at Sarnath, the city in India where the Buddha himself began to teach. "Most of them won't understand head or tail of the initiation, but they're hoping at least to get part of the blessing from the holy gathering, to catch a glimpse of the Dalai Lama."

The Chinese were issuing limited numbers of temporary travel permits— none to monks or nuns. False travel permits, which were actually hospital admission cards, were selling like hotcakes in Lhasa for two yuan a piece to illiterate devotees. The soldiers were tearing them up at the border. A lot were sneaking over without permits, hiding in the backs of trucks and hiring Nepali coyotes to guide them across, which was risky because some of the coyotes for a second fee turned the refugees back to the Chinese border guards. For those who already had a record of demonstrating, refoulement was death.

The son of nomads, Sonam had left Tibet in the '59 diaspora at the age of eight, and he knew a great deal about the nomads' folk beliefs. He told me about some Lilliputian beings less than a foot tall, called samishingmi, who sat on

mule dung for benches and used blades of grass for arrows. "When I was a kid, my parents told me not to roll boulders down the hill onto the prairie, because they would scratch the surface of the grass. There was a place called Crystal Hill where rock crystals sparkled in the sun, but we were forbidden to break them off because they were the toys of the spirit babies." He told me that turtles were believed to be reincarnated "miser men," who, having never offered hospitality to anyone in their previous lives, were condemned to carry their houses around wherever they went.

"Everybody was tortured. Some went crazy. Only one-third of those who go to prison can come back to normal life."

We turned up a path that ran between fields where women in vibrant saris were putting in their last crop of cauliflower and white radish. The Balagu refugee camp was a former factory: two stories of rooms facing an inner courtyard. In the mess hall, all of the hundred or so refugees were glued to a video of the Dalai Lama. Catching sight of me, some of the refugees put their tongues out, a traditional gesture of goodwill and respect which, Sonam explained, was originally intended to show that one was not a Bon practitioner; practitioners of Bon, the shamanistic religion that preceded Buddhism, were said to have had blue tongues.

I spent the afternoon debriefing small groups of refugees. One of them was composed of three young nuns from the Ani Tsangkhun Convent in Lhasa. With their shaven heads and round faces they were quite indistinguishable from the young monks, except that their robes were brown, while the men's were maroon over saffron. Lobsang, a hefty twenty-year-old with an irrepressible smile and a sparkling gold eyetooth, said that she and her friend had gone over the ice wall of the Himalayas, the most imposing natural barrier on the planet, nineteen days before.

In the next batch of three nuns, two couldn't stop giggling. The other looked grim, hurt, angry. It was clear that something terrible had happened. Her name was Kunsang, and she said she had spent six months in the Kutsa Prison for putting up posters. Her brother had been shot dead through the neck in the big March demonstration.

What was it like in the prison?

"Everybody was tortured, except the snitches. Some went crazy. Only one-third of those who go to prison can come back to normal life. Two-thirds are permanently disabled. Our fellow nuns could bring us food once a month. I was stripped, kicked all over." Her lower lip began to quiver violently.

What now? I asked.

"I have no personal plans, except to continue to fight for the cause of Tibetan freedom."

The video had ended and everyone was out in the courtyard enjoying the last hour of sun, laughing, playing cards. A dozen faces were pressed to the window. A rack of pleated, monsoonslashed foothills rose in the background. Behind them stood the breathtaking white wall of the Ganesh Himal, and over the wall was Tibet—the forbidden country.

THE GREAT FOURTEENTH

An old British hill station in Himachal Pradesh, India, 125 miles from the Tibet border, where the viceroy and his entourage summered in the heyday of the Raj, Dharamsala is now the seat of the Tibetan government in exile. A faint aura of the sixties hovers over the place. The flower children who hit the orphic trail to India in the late sixties and early seventies were among the first to discover Dharamsala and the Dalai Lama's message of global harmony through personal transformation. Hundreds of thousands never returned from the subcontinent (150,000 French alone it is said), and, middle-aged now, they are part of the landscape like the Bakhtis, or Shiva seekers, and all the other indigenous (Continued on page 102) (Continued from page 98) varieties of wandering mendicant longhair. The Tibetan medicine clinic of Yeshi Donden, the Dalai Lama's former personal physician, was packed with emaciated, toothless old dharma bums.

That there was an exile government that handles the problems of the refugees and is ready to return at a moment's notice should China collapse and the "liberators" leave was truly impressive, even though the inevitable court intrigues and power struggles had carried over from the ancient regime, the chain of access to His Holiness was jealously guarded, and, as Khandro Chazotsang, a woman in the Home Office in charge of the rehabilitation of new arrivals, told me, a "babuji element," the British-influenced clerk mentality that makes the Indian bureaucracy so impossible to deal with, had crept in.

The seed money for the exile government came from the treasure brought out by the thousand-plus pack animals in 1950, stashed in a stable in Sikkim, and cashed for—accounts vary—$1 million or $8 million. All Tibetan exiles everywhere (there is a sizable contingent in Switzerland, for instance) send contributions. The orphans at the Tibetan Children's Village above Macleod Ganj, run by one of the Dalai Lama's sisters, have individual sponsors. The Indian government gives relief, and there are some private Western donors. (Although it hasn't had a vogue the way the rain forest has, the Tibetan cause has ardent supporters ranging from Abe Rosenthal to Richard Gere.) The dollar goes a long way here.

But there is no help from the United States government. In the beginning, America perceived that the Tibetan freedom movement could be useful in the war against Communism and backed it, as it did the contras and the mujahideen. Tibetan freedom fighters, kept in the dark about where they were going, were flown to Camp Hale, Colorado, where they were trained by the C.I.A. under utmost secrecy in techniques of guerrilla warfare, armed with the latest sophisticated equipment, and flown back to the plateau. But then, in 1971, Henry Kissinger advised Nixon to buddy up to Mao so they could work together against the Russians, and aid to the freedom movement was abruptly terminated. A pawn in a larger power game, Tibet was sacrificed. Avedon relates how the guerrillas were hunted down and, finally, sandwiched between Chinese and Nepali troops, slaughtered, and how their bravest leaders, ordered by the Dalai Lama to desist from violence, slit their own throats rather than disobey him.

George Bush was Nixon's envoy to the People's Republic, and he remains its loyal fan. In 1977 he was taken to Lhasa and snowed by the Tibetan Revolutionary Museum, below the Potala,

In 1989, the Dalai Lama was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. Congratulations from the White House were not forthcoming.

where amputated hands of criminals, flayed skin, implements of torture, human-thighbone trumpets monks had blown, and evidence of other alleged atrocities of the "liberated Lamaist feudal state" were on display. The State Department refused the Dalai Lama visas in 1960 and 1977 for fear of upsetting the Chinese. Finally, in 1979, he was let in, but to date no American president has dared to shake his hand. The Soviet peril has subsided, but China still contains a quarter of the world's market.

I had asked Tenzin Geyche Tethong, the Dalai Lama's private secretary, for permission to observe some of the other audiences His Holiness was having. It had been granted, and that afternoon I walked up to the Tegsum Choeling Temple, the main temple in Dharamsala, which is out on a spur of the ridge that overlooks the vast Kangra Valley, thousands of feet below. There was something almost sci-fi about the scene, like walking into this futuristic factory for enlightened beings. In the yard, pairs of young shaven-headed monks, in ritual combat stance, were thrusting their arms at each other. I thought they were practicing martial arts, but in fact it was dialectics. From inside the temple came the flatulent blats of long brass horns called dung-chen and the steady drone of oboelike gyaling. I stepped through a gate guarded by Indian soldiers into the adjacent executive compound. A plainclothes Tibetan frisked me and searched through my side bag. Nothing had happened yet, but there was always the danger of a crazy, like the one who shot Gandhi, getting through.

The audiences took place in a villa up the hill. The first was with a group of pilgrims—humble steppe people in tribal shawls who had come all the way from Ladakh for His Holiness's blessing. His Holiness came out on a veranda dripping with bougainvillea. He wore olive-tinted glasses and maroon monk's robes. The pilgrims approached him in a line, one by one, bent over, not daring to look at him. As a retainer held a black parasol over him, he also bent over and presented each of them with a blessing cord and a packet of blessed pills. All this happened in silence, broken occasionally by His Holiness asking in a rich, deep, resonant voice questions like "Which route did you take?, ' ' grunting ruminatively, or breaking out in a basso burst of laughter. (The Dalai Lama has "a wonderful laugh," The Washington Post reported on his first American visit. "It surprises itself in the act of delight and rings out around the room, as if all his past thirteen incarnations were joining in.") Then all the pilgrims backed away from him, taking a last longing look, some mumbling mantras a mile a minute, a few with tears of joy streaming down their cheeks. All this took no more than five minutes, although it seemed to be happening in slow motion.

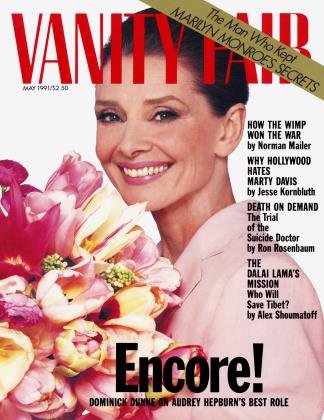

As I watched this tableau of adoration, I reflected how the Dalai Lama could have spent the rest of his life living comfortably in the South of France, receiving the occasional visitor for tea. But instead he has been working tirelessly for his people, and indeed for all mankind. In 1989, he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize, the only Asian to have won it on his own. The Chinese called the award "preposterous." Congratulations from the White House were not forthcoming.

The more I thought about his message, the more I was taken by it. His policy of Universal Responsibility, derived from the Buddhist kinship with all "sentient beings," contains the seeds for the salvation of the planet. He advocates a politics of compassion, not of chess—the old Machiavellian Kissinger approach which has brought us to the brink of self-immolation. The problem is, is anybody in power about to listen to him?

Maybe, I began to think, it was no mistake that the Dalai Lama was driven from his isolated land. Maybe he came out to help bring about the much-discussed "new world order"—or what's left of it since the Baltic crackdown and the holy war in the Gulf—whatever meaning the term retains since its adoption by George Bush.

My first question, when the two of us were alone together, was about the new geopolitical shape the world is struggling to assume, how at the same time that it's growing together it's breaking up into small, independent states, reBalkanizing. Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia, Georgia, Moldavia, want out of the Soviet Union.

The Kashmiris and the Sikhs in the Punjab have no desire to be a part of India. Outer Mongolia (where the Dalai Lama is giving the Kalachakra initiation this summer) is already an autonomous satellite; opposition parties are allowed, there are free elections and a tremendous resurgence of Buddhism, which was crushed by the Bolsheviks. It's a model of hope for Tibet. The longing for self-determination is spreading into China. The Uighur Muslims in bordering East Turkestan are as eager for the Chinese to leave as the Tibetans are. The economic zones around Shanghai, having tasted free enterprise, would love to check out of the People's Republic as well. My question was: Suppose all these people actually get their freedom—is that really the instant formula for world peace? Won't it create new opportunities for territorial aggression and ethnic and sectarian strife? Won't everybody soon be back at each other's throats?

"Because of economic situation, world must come.together on free basis, without losing individual identity," he replied in Pidgin English, devoid of unnecessary subjects, verbs, and articles and amazingly effective and to the point. "Economy and ecology now extend beyond national borders. Soviet and Chinese collectiveships were imposed without freedom, so they won't work now. They're collapsing, aren't they? My idea is that war something oldfashioned. Everyone want peace. But peace not just absence of war. For forty years there has been no war in Europe, but this not genuine peace. It has been out of fear of nuclear war. The new peace genuine because from mutual respect.

"All continents must demilitarize, each individual nation, one by one. Europe will be first. But some mischievous elements will happen, so to protect there must be some kind of collective member-state force. Each state contribute same number of police, on rotation system, and everybody must stop making business from weapons. That is the real cause of instability in the Middle East and everywhere."

His recognition of the need for some kind of peacekeeping force was an important point, I thought. On many occasions the Dalai Lama had said things

"This has been most complicated century in human history," says the Dalai Lama. "I believe next century will be happier"

like, Your enemy is your best friend and should be a special focus of compassion, because it is he who makes you grow, and had claimed to be sincerely grateful to Mao for teaching him the realities of suffering and impermanence. This and the central doctrine of Buddhism that nothing is inherently real didn't seem very useful attitudes when someone is pointing a gun at you. But in fact surgical or preventive violence is not only allowed by the bodhisattva ethic, it is required. You must take out a mass murderer if you can, or you yourself become an accomplice. But you must do it in a detached manner, without hatred or anger. It's O.K. to defend yourself, and the reason the Dalai Lama tells his people to cool it with the Chinese is purely realistic: they are six million to the billion-plus Han.

"I always thinking entire humanity as one," he went on. "National status not so important. But under present circumstances I am concerned about identity of Tibet and other small nations. We must distinguish between temporary and longterm goals. Long-term goal is that whole world become one nation. Short-term goal is self-determination for all individual states. In a family, many brothers and sisters living together. For harmony, each individual identity must be fully respected. But extreme individualism neglects others' rights and will bring disaster. Too much self-centered, lose genuine friend. During Korean War, Asians got impression that Americans were champions of liberty and democracy. That image disappeared due to certain politicians' actions. When only interested in self-interest, begin to lose friends. Cooperation is a genuine human quality. The other way, one nation exploit the others—a new type of colonialism. But the world economic situation will teach us our future.

"From Buddhist standpoint, if a national struggle is purely political and not spiritual, it is hard to justify. But our struggle is not only political, it is for preservation of the dharma, and preservation of Tibetan culture is indirectly of benefit to China. Buddhism not alien religion to China.

"For Tibetans, present time is worst and darkest period of our whole history. In this century greatest number of humans killed, and techniques of destruction immensely increased. This has been most complicated century in human history. We learned much and became more mature. It is human nature, when facing desperate situation, to use more intelligence. I believe next century will be happier."

An hour later, we had turned from the problems of the world to some of the more esoteric aspects of the religion, like the trance walkers, or lamas lung gompas, who having mastered wind meditation are said to be able to cover great distances in buoyant, bounding leaps, streaking at forty to fifty miles an hour completely tranced out. He told me about an old nun who claimed to have watched, years earlier in the old Tibet, two highly realized hermits fly a hundred meters from one rock to another. "We believe training of mind, mental force, can overpower physical elements, and these unusual feats not so impossible. "

Just as it was starting to get interesting, Tenzin Geyche Tethong ended the audience. The next group, some recent arrivals from Tibet, was waiting. We went into the other room, where they began prostrating. Among them I recognized Lobsang, the roly-poly, redcheeked nun with the gold eyetooth and the irrepressible smile whom I'd interviewed in Kathmandu two weeks before. Not daring to look up, she didn't recognize me. This was the first time any of them had set eyes on their ruling archangel, and he was there for them, as he had been for me. Leaning humbly, attentively, over the bowed group, he told them, "Work hard, study hard. Now you are in exile, but you are free."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now