Sign In to Your Account

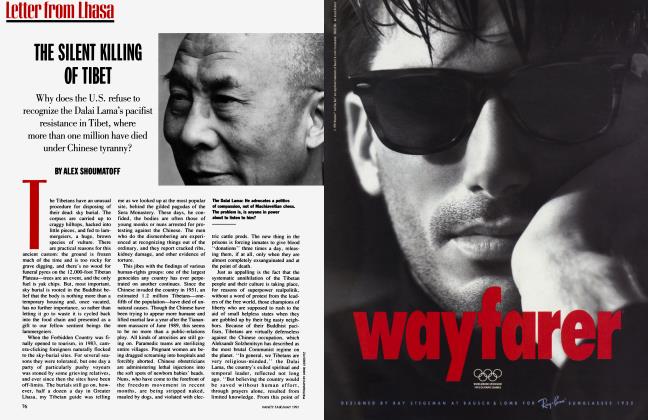

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

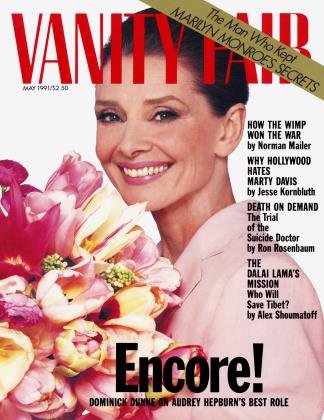

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowWHY HOLLYWOOD HATES MARTIN DAVIS

The Paramount C.E.O. blew off the top-gun troika of Eisner, Diller, and Katzenberg, sideswiped Time Warner and Art Buchwald—now he's wreaking havoc with Frank Mancuso's exit

JESSE KORNBLUTH

Show Business

Ladies and gentlemen of the jury," Art Buchwald began, and the laughter was instantaneous, because just about everyone at the 1989 Variety Club dinner honoring Martin S. Davis knew Buchwald and Davis were embroiled in a dispute that was no joke. "My role tonight is to heap praise on Martin Davis," Buchwald continued. "Now, this happens to be a conflict of interest. You see, the fact of the matter is I'm suing Paramount Pictures, one of the companies Martin owns. So how, you may ask, did I get to this dinner? Well, the lawsuit is nothing more than an honest disagreement"—and suddenly Buchwald's raspy voice cracked, betraying the hurt he was really feeling—"between good friends. I say Paramount screwed me. And they say they didn't."

Buchwald went on to recall that when Davis first invited him to be this evening's toastmaster he declined—only to find a dead horse at the end of his bed the next morning. The crowd roared. Afterward, no one said he'd gone too far. Maybe what Davis had told him about the lawsuit and their friendship was right: One had nothing to do with the other.

It does now.

In January 1990, Los Angeles Superior Court judge Harvey Schneider ruled that Paramount's Coming to America, an Eddie Murphy vehicle that grossed more than $300 million, had indeed been inspired by a two-and-a-half-page treatment the studio had bought from

Buchwald and producer Alain Bernheim. And that was only the beginning of this landmark decision, for just before Christmas, Judge Schneider decided that Paramount's contract with Buchwald and Bernheim was "unconscionable" and "unduly oppressive." Moreover, Schneider condemned the entire contracting system, proclaiming the netprofit clause embedded in the boilerplate to be invalid for all seven of the major studios. His conclusion—"The net-profit formula as written no longer exists"— certainly suggested that anyone in film, television, or the music business who had a contract promising a share of net profits might profitably find a lawyer.

The judge is now determining what Buchwald and Bernheim are owed by a studio that still contends one of the topgrossing movies in the history of the entertainment business is $18 million in the red. For its part, Paramount indicated it would appeal; observers say this case might even wind up, years from now, in the U.S. Supreme Court.

But Hollywood doesn't need that long to reach a verdict. "A cancer—they should have paid him the five dollars," Lew Wasserman reportedly said at a dinner party. Studio heads have traded unprintable epithets about Paramount's eagerness to face America's best-known humorist in a courtroom packed with reporters and television cameras. Only Buchwald remained placid. "1 don't get upset at Paramount," he said recently, "since I discovered they are a nonprofit organization."

Frank Mancuso was not a sometime friend like Art Buchwald—he'd been at the studio for thirty years, almost his entire working life, and had been its highly successful chairman since 1984. Loyalty has many rewards. In this case, it meant that Mancuso heard a full several hours before the rest of the industry that Stanley Jaffe, a producer who worked for him, was about to be his boss. After dropping the boom in an early-morning phone call, Martin Davis flew out to Los Angeles to finish off the job. He reportedly assured Mancuso that Jaffe, as president and chief operating officer of Paramount Communications, was also going to oversee Richard Snyder at Simon and Schuster. It wasn't so bad, he said. Mancuso would get to keep his title; he would simply confine himself to distribution and marketing, leaving the "creative" decisions to "creative" people. Mancuso stormed off. The next day, Martin Davis was sitting at his vacated desk, and Mancuso was preparing to file a $45 million suit for wrongful termination.

Studio insiders had sensed that something big was in the air several months earlier, when new production executives, with Mancuso's blessing, began reviewing long-term producing deals. Foremost among them was that of JaffeLansing, which had brought the studio Fatal Attraction and The Accused, but which had also spent a fortune on developing nearly a hundred scripts. Now Jaffe wanted to direct his second feature. The studio balked. Jaffe went over Mancuso's head and got Martin Davis to approve the project. It was during those conversations that Davis suggested Jaffe might like to direct more than a movie.

For longtime observers of Davis's take-no-prisoners management style, there was a quality of deja vu to Mancuso's forced exit. In 1984, a year and a half after he succeeded Gulf & Western founder Charles Bluhdorn, Davis shocked Hollywood by letting Barry Diller, Michael Eisner, and Jeffrey Katzenberg leave Paramount, a move that confirmed Fortune's wisdom in having named him one of "The Toughest Bosses in America.'' In 1989, he stepped into the Time Warner merger just two weeks before the deal was to close. His willingness to play the spoiler forced Time Warner to take on an additional $9 billion in debt, crippling its expansion plans for years to come; Davis's impulse, meanwhile, cost his own company a whopping $55 million in investment-banking and legal fees.

With movie earnings down, there had been jitters at the studio for months, ever since "a bunch of suits" blew in from New York, according to one executive, and "shook the trees." The presence of Stanley Jaffe on the lot has done nothing to calm executive terror. And his hiring has caused a considerable stir at Simon and Schuster, where Richard Snyder has long squirmed under Davis's thumb. In recent months, according to some observers, Davis had used such embarrassments as the American Psycho controversy and the firing of an editor as excuses to put Snyder on the spot. After the Jaffe announcement, Snyder was ordered to release a statement indicating he was so happy about his "close and comfortable" relationship with Davis that he wanted to finish his career at S and S. "No one knows where this will end," a Simon and Schuster editor told me. "Dick could lose his job. He should leave—but where would he go?"

The resentment against Davis that has boiled up in recent weeks might make civilians wonder why Jaffe, who is adept in the politics of the movie business, took any job with this company. Insiders all suggest Jaffe knows something—that he may not have to endure Davis for long, for with a new leader in place, Paramount is in a better position to sell the studio. "Stanley will leave rich and

Mancuso heard a full several hours before the rest of the industry that Stanley Jaffe was about to be his boss.

early, a la David Geffen, though not on that scale," a Paramount expert told me.

Finance was also cited as the official reason for the changes at Paramount. The studio has taken almost $200 million in write-downs in the last year, and when Davis launched a prosecutorial approach to cost-cutting, Mancuso's men did little more than lop $8 million off the budget for Star Trek VI. But the real reason for the shake-up was personal: Frank Mancuso had gotten Marty Davis into trouble. "Davis is a rare animal," a studio executive musedi "He thinks these things out all by himself, does them, and finds that they make no sense whatever. This conservative, wing-tipped guy who says he hates Hollywood excess is truly much more reckless than people out here."

In sending Jaffe, a more polished version of himself, to run the studio, Martin Davis was making a strategic retreat from the town that hated him. Wall Street was unimpressed, however; the stock dropped three points in the week after the Jaffe hiring. "What was regarded by some as a decisive move was in fact an expression of confusion," a Wall Streeter told me. "What next? Does the emperor have any clothes?"

Such skepticism in financial circles should trouble Martin Davis, for the one place he has found appreciation is Wall Street, which during the 1980s had no trouble reading his balance sheet or his passionate commitment to shareholder value. He was a hero then, the man who had inherited an unruly conglomerate and turned it into a streamlined gem of his own—the appropriately renamed Paramount Communications Inc., America's last pure, unmerged entertainment-and-publishing company.

As he enters the nineties, Davis is still a Wall Street hero, for one highly visible reason: he's sitting on $1.8 billion in cash, plenty of money to buy something or make Paramount an attractive merger candidate. But he has been sitting on that fortune for eighteen long months, with no acquisition or merger in sight, and that inert cash has come to suggest a very different picture: a takeover bid that could lead to Davis's demise.

If that occurs, many in Hollywood and in publishing circles will cheer. Although Frank Gifford calls him "one of the nicest people I've ever met" and praises him for helping to raise more than $25 million over twenty years for the fight against multiple sclerosis—a disease no one in his family has had—a more common take on Davis is that he's extremely prickly. "When you first meet him, he may try to put you down, and if you take it, you're dead meat," says a man who knows him well. And these put-downs are not the kind that presage male bonding. "It's 'Your shoes are dirty' and 'You're putting on weight,' " a former associate says.

Of the many people I called, only a handful were willing to speak for attribution—Martin Davis is feared. His exwife, Dolores, assured me she wasn't afraid of him, but she too declined to be interviewed. "I've been Martin Davis's best friend," she said with considerable emotion, ''because I have never spoken about him." I understood one reason for her bitterness when I read the New York Times death notice for Martin Davis Jr., who died on Christmas Day in 1986. It listed him as the ''beloved son of Martin S. Davis [and] step-son of Luella Davis, ' ' omitting any mention of his mother.

Why does Martin Davis go out of his way to make sure everyone knows he's one tough hombre? It's certainly not because of any obvious trauma in his past. The son of a Bronx real-estate speculator, he was so eager to join the army that he left school at sixteen in 1943; thrown out for lying about his age, he re-enlisted as soon as he finished high school, serving in the criminalinvestigations division of the military police's counterintelligence corps. When the war ended, he did a stint as an office boy and later became a movie publicist for Samuel Goldwyn, and, at thirty, was hired by Paramount, where a former boss remembers him as ''a fucking mealymouthed bag carrier with no talent at all."

By 1965, he was Paramount's chief operating officer and executive assistant to the president. But not, it appeared, for long. Takeover bids were swirling around Paramount, and Davis was dispatched to find a white knight who would save the studio. Davis produced Charles Bluhdom. And Bluhdom produced an immediately attractive offer of eighty-three dollars a share.

Bluhdom, a lifelong bargain hunter, made such a generous bid for Paramount in part to thumb his nose at Wall Street, where he was regarded as a bottom fisher in perennial search of undervalued assets. "The mad Austrian," Life called him, and the magazine was, on a level, absolutely correct—Bluhdom had built Gulf & Western into a crazy-quilt conglomerate of one-hundred-odd companies dealing in everything from panty hose to sugar. "Engulf & Devour," Mel Brooks joked, and almost to the end of his life, Bluhdom showed no signs of a diminished appetite; even at Casa de Campo, the company's retreat in the Dominican Republic, his greatest pleasure was buying and selling stock. "It would get to be three A.M. and Charlie would sit down and trade until dawn," an associate recalls.

"Paramount was the greatest prize Charlie ever bought," a close friend says. "It gave him visibility and entree." And not just to Wall Street respectability. "Old-timers won't mince words about it—Paramount was the biggest purchase for pussy in the history of America to that time," a studio veteran says. "Charlie loved that Bob Evans [who was head of production at the studio in the late 1960s and early 1970s] knew a great many models and actresses." There were also professionals around. "Charlie sure loved to party," says Madam Alex, who once catered to the whims of powerful Los Angeles men.

"Paramount was the greatest prize Charlie ever bought," a close friend says. "It gave him visibility and entree "

Bluhdom's passion for the studio was not accompanied by an instinct for filmmaking. Fortunately, he acquired the services of Barry Diller and Michael Eisner, and allowed them to run the studio. Davis, meanwhile, became known as Charles Bluhdom's "henchman." If he was pained by this role, he hid it well. "In the late sixties and early seventies, Paramount wasn't doing well, and it was decided that we needed to cut the staff in half," recalls a former human-resources executive at the studio. "Many of the people we got rid of had been at Paramount since the beginning.

They had no pensions, no benefits, no nothing. Marty was removed, but he should be held accountable."

Yet iciness was just what Bluhdom needed. When the S.E.C. began an investigation of a G&W executive, Bluhdom chose Davis to represent the company. And when Seymour Hersh, then a New York Times reporter, was preparing a three-part series on G&W for the paper's front page in 1977, it was Davis who was deputized to shout at him. "Davis was formidable," he says. "He played total hardball. But compared to Charles Bluhdom, he's the most virtuous man I ever met."

Bluhdom fought a five-year bout with cancer, but when he died—of a heart attack—in February 1983, he had made no provisions for a successor. The obvious choices were G&W president David "Jim" Judelson and executive-committee chairman John Duncan, men who'd been with Bluhdom from the beginning. There was also some support for Barry Diller, who quickly declined. So, in the early discussions, Davis was a distant fourth.

Davis's political savvy and years of experience in public relations served him well in the days after Bluhdom's death. Especially important was his attentiveness to Diller and to Bluhdom's widow, who inherited more than three million shares. In an interview Diller gave to Alex Ben Block for his book Outfoxed, he insisted that Davis promised to make no changes at Paramount— and that this pledge was the reason he backed Davis. (Davis has denied ever making the promise.) There is similar confusion about Davis's conversations with Mrs. Bluhdom. "He promised Yvette that she would have all her husband's perks," says a man who was privy to the discussions. "He told her there would never be another chairman and Charlie's office would be kept as a shrine."

A month after Bluhdom's death, the Davis appointment was announced. The stock, which had risen slightly on the news of Bluhdom's death, was now up 47 percent, giving Davis all the encouragement he needed to begin dismantling the unwieldy conglomerate. Within a year, he had stripped Mrs. Bluhdom of her car and driver, her direct phone to the G&W office, and her other perks. He'd had himself named chairman. And he'd moved into Charles Bluhdom's office.

It was only a matter of time before Martin Davis made his power felt in Hollywood.

Of Barry Diller's many accomplishments at Paramount Pictures, his greatest may have been championing Michael Eisner. "When Barry brought Eisner in, it was electrifying,'' a G&W veteran says. "Before that, the studio made $10 or $20 million a year, $40 million if we were lucky. Diller and Eisner gave us seven or eight years of unqualified success, making more than $100 million, year in and year out."

And yet Diller has recalled that, early in 1984, Martin Davis ordered him to fire Eisner. Diller fought him off, but Davis still seethed; according to Outfoxed, Davis was convinced that Eisner wasn't a team player, that he put selfinterest over loyalty. That summer, the crisis was brought to a head when New York magazine published a piece called "Hollywood's Hottest Stars"—about Diller, Eisner, and Jeff Katzenberg. Davis loathed the piece. To him, both Diller and Eisner were overpaid and overrated, and at contract time he was determined to do something about their 57 percent share of the executive-bonus pool. Diller beat Davis to the punch; shortly after Labor Day, he left Paramount for an even richer deal as chairman of Twentieth Century Fox. " 'There's no reason to get on a plane— we'll handle everything in New York,' " Diller recalls Davis saying when he resigned. "By seven the next morning there was a release on every employee's desk in which Davis tried as best he could to portray it as if he had fired me."

With Diller gone, Eisner was poised to take over. He and Katzenberg were summoned to New York to meet with Davis. No corporate plane was made available to them, so they flew commercial. This may not have been an accident—at that time, commercial jets weren't equipped with phones. As a result, there was no way anyone could have tipped off Eisner and Katzenberg to what was happening at the Gulf & Western tower.

Eisner and Katzenberg went directly from the airport to a late-night meeting with Davis. The C.E.O. had one question: If Frank Mancuso, who had risen through the marketing and distribution ranks, became head of the studio, would Eisner be willing to report to him? Eisner said he would not. O.K., Davis said, he'd think it over. But at three in the morning, when the two returned to the Regency hotel, Katzenberg pulled a copy of The Wall Street Journal from a freshly delivered stack and read that Mancuso was being appointed Paramount chairman later in the day.

Now it was Eisner's turn to move fast. At noon, he asked Davis to produce— immediately—his $1.55 million bonus check. At three P.M., his resignation was announced. Eisner was soon ensconced at Disney. Katzenberg followed. So did thirty other Paramount executives at the vice-president level or higher—almost half of Paramount's senior management. Martin Davis's first significant decision at Paramount had decimated his studio.

For one of the moguls who would have to deal with Davis in years to come, the defections were chilling. "1 hate to be in a business situation where I can't rely on the other guy to act in his own interest," this man said recently. "Marty Davis doesn't play by that rule— he's motivated more by the will to dominate than by money, and that makes it hard to deal with him. Diller, Eisner, Katzenberg—these may be the three greatest film executives in fifty years. The day Davis let them go, he ran a good chance of destroying the company."

But, as it happened, Frank Mancuso really could run a studio. Indeed, armed with projects that his predecessors had left behind, he produced even greater revenues in the mid-1980s. "And that," the mogul told me, with more regret

During a breakfast at the Regency hotel, Davis 'look out a dollar and sort of waved it at me as a joke," Buchwald recalls.

than envy, "gave Marty Davis a sense of awesome power."

There were the people Martin Davis got tough with, and then there were the people he coddled. Even back in 1983, when Eddie Murphy was just twenty-one and coming off 48 Hrs., he was someone to pamper. Which is why, at a carefully orchestrated dinner at Ma Maison, Paramount executives were trying out a dozen or so movie ideas on him. One that appealed to him was about a rich African king who comes to America, loses his money, and finds himself working for chump change until he meets the love of his life and, queento-be in tow, returns to his kingdom.

He might well have been amused— the writer was Art Buchwald, whose column was then syndicated in more than five hundred newspapers and who had won a Pulitzer Prize for his pithy commentaries on American foibles.

Two years and $350,000 in scripts later, Paramount dropped the Buchwald project. His producer took it to Warner Bros., which commissioned a script of its own. Then, in 1987, Paramount announced it was making Coming to America, an Eddie Murphy movie from an Eddie Murphy idea. The director was John Landis, who'd been approached in 1983 as a potential director of the Buchwald-Murphy movie. Warner Bros, saw that announcement and dropped the Buchwald project. Buchwald saw the announcement and, after thinking it over for a while, went to see a lawyer.

And not just any lawyer—he picked Pierce O'Donnell, managing partner of Kaye, Scholer, Fierman, Hays & Handler in Los Angeles. O'Donnell is a jolly man, with a considerable flair for the sound bite. "If they ever abolish arrogance and greed at studios," he likes to say, "I'm out of work." He's in small danger of unemployment: in 1985, he separated $50 million from Columbia for his client Danny Arnold, the creator of the Barney Miller television series.

In the summer of 1988, around the time Art Buchwald saw Coming to America ("an awful movie, but it was my awful movie") and hired O'Donnell, he ran into Martin Davis at a party. "I'm not sure I should talk to you," Buchwald said. "I might have to sue you." Davis waved him off. "No one can steal from my friend," he replied. "I'm going to look into it and get back to you."

"And," Pierce O'Donnell observes, "he never did."

That wasn't the only shot Buchwald fired across Davis's bow. There was a Liz Smith column that read like an open letter to Davis. There was a breakfast at the Regency hotel where Davis sat a few tables from Buchwald. "He took out a dollar and sort of waved it at me as a joke," Buchwald recalls. "I didn't respond. I didn't know how to behave." That fall, Davis asked Buchwald to be his toastmaster for the Variety Club dinner. When Buchwald again mentioned the forthcoming suit, Davis sent him a bottle of Dom Perignon and a cassette of a song from Guys and Dolls—"Sue Me."

A frustrated Buchwald realized that "Marty just didn't think I was serious."

That fall, O'Donnell filed for $5 million in damages; he says his client would have taken much, much less. A company with a C.E.O. who is a former publicist might have seriously explored a settlement. Paramount didn't. As a result, half of the courtroom's sixty seats at the first Buchwald trial were occupied by reporters. Fox TV—that's Barry Diller's company—gave it ample coverage. In three years, Buchwald and O'Donnell have burned through three lead lawyers for Paramount, and Pierce O'Donnell has become a media star. "1 took the contract from around my shoulder and wrapped it around Paramount's throat," he exults.

The studio fought back: near the end of the first trial Paramount's lead lawyer suggested that in fact Buchwald's treatment had ripped off the plot of Charlie Chaplin's A King in New York. In his summation, O'Donnell thundered: "This is an intentional act by Paramount Pictures to hurt Art Buchwald. It's not just dirty pool, it's scurrilous conduct."

A few months later, at a party honoring Helen Gurley Brown's twenty-fifth year as editor of Cosmopolitan, Martin Davis went over to Art Buchwald. "You told me not to get involved," Buchwald quotes him as saying. "And I didn't, and look at me now. Can we talk about this?" Buchwald felt he couldn't excuse the plagiarism charge. It will now be up to Jaffe to seek forgiveness—and a settlement.

In 1989, Davis sold Associates First Capital, Paramount's financial-services subsidiary, to Ford for $3 billion. If he had had his way, his vault crammed with cash would be empty now—in that dream, Martin Davis is presiding over the world's premier entertainment company, a colossus that includes the biggest commercial and educational book publishers and the largest magazine group in America, the most successful film studio, a very profitable television subsidiary, and Madison Square Garden with its sports teams, the Knicks and the Rangers. To be sure, the stock price plummets and his investors don't see dividends for some years, but at some point in the 1990s the synergy kicks in and Paramount leaves everyone else in the dust.

Davis had proposed versions of this scenario before, to ABC, Time, and Sony, but it wasn't until Warner was about to conclude an old-fashioned stock swap with Time that he made a formal move. His offer of $175 a share for Time stock turned a merger into a bidding war and threw the battle into the Delaware courts, where the primacy of shareholder value is not as clear as it is in the Paramount offices. Davis lost.

"We were shocked when Paramount came in, because we were partners with Paramount in the theater business," Time Warner chairman and co-C.E.O. Steve Ross told a reporter. In another part of the Time Warner camp, David Geffen commented upon Davis's apparent disdain for long-term thinking: "This is a world built on relationships, and Davis showed relationships don't mean much to him."

Neither, apparently, did economics. Had he succeeded in winning Time, Davis would have been deep in debt, with no easy way to pay it off in an increasingly unfavorable economy. "He would have had to go under or trash the company," a former associate says. "By not getting Time, Paramount was saved." Why did Davis bid for Time in the first place? "Pique," this source believes. "He couldn't stand it that Time and Warner got together."

"It was stupid," another Bluhdorn associate says. "If Paramount had let that merger go through, it might have put an end to these crazy prices—and Marty Davis might have been able to |merge) with somebody else. Instead, he whetted the appetite for even higher prices. And there was no second plan. 'We go after Time, we lose it, that's it.' "

In fact, Davis improvised an alternative plan: with some of the Associates windfall. Paramount bought back roughly five million shares of its stock. But his unwillingness to go beyond that move, critics say, suggests Davis's limitations as a manager for the 1990s. "Matsushita buying MCA was a borderline call," one skeptic told me. "The next Japanese company that buys an American communications business goes over the line—particularly an American business that publishes textbooks. As for Davis, he won't buy anything; it's not his way to pay the premiums media companies command. O.K., so he goes for a merger. With whom? Put him with a Tisch. Tisch eats him up, so he can't go that way." Despite the persistent rumors that Paramount is vying with Disney to buy. or merge with CBS, this skeptic concludes that Davis has played almost every card in his hand.

This has left him curiously vulnerable to cycles in the communications business—particularly the film business. "You make a few $50 to $60 million films that flop, you take a huge writeoff, the stock drops to $25," fantasizes Jeffrey Logsdon, the much-respected entertainment analyst for Seidler Amdec. "Around the comer comes Whirlwind Charlie with a thirty-five-dollar-a-share bid—you don't want that."

Once again, it seemed, Martin Davis was going to have to kick some ass at the studio.

The 1980s, at Paramount, were the "franchise" years. "Event movies," they called them. "Tent poles." Whoppers that hit big and kept on gushing—for, according to the Mancuso gospel, if you scored with Raiders and Beverly Hills Cop and 48 Hrs., you made sequels. Cost was not the primary factor; grosses were.

As the decade ended, Paramount found itself at the mercy of two of its most successful franchises. First to express his discontent was Eddie Murphy, who many in Hollywood believe is destined to be reunited with his former Paramount mentor, Jeff Katzenberg, at Disney after he makes the final two movies on his current contract. Paramount would like to reason with Murphy. To do that, though, the studio must have a relationship with him. Frank Mancuso tried to broker one, but, according to an oft repeated story, the Mancuso-Murphy sit-down at Morton's was a disaster: after keeping Mancuso waiting for forty-five minutes, the star arrived with half a dozen bodyguards, reamed the studio chief out for fifteen minutes, and left.

The other franchise was the producing team of Don Simpson and Jerry Bruckheimer, the most consistent money-makers of the 1980s. Flashdance, Beverly Hills Cop I and II, Top Gun—the $62 million these movies cost to make brought in $2.3 billion in worldwide revenues and created around $1 billion in profits for Paramount. Their deal was scheduled to lapse in 1989; predictably, they were widely courted. After a twoyear negotiation, they decided to stay at Paramount—and wallow in the richest deal in the history of the movie business.

The trouble began almost immediately, with a full-page ad in many newspapers proclaiming a "visionary alliance." Simpson's explanation of that alliance, though accurate, was hardly politic:* "They finance the movie, we make the movie, they market the movie, we meet at the theater." Nor did Simpson win friends when he advised production head Sid Ganis at a range of maybe six inches, "I will not speak to you, because you have nothing of interest to say."

Then they actually made a movie.

Days of Thunder made its release date, but from Paramount's standpoint that's about all it made. In a summer when films like Total Recall produced $116 million, Thunder brought in $80 million, a "disappointment" to the studio, which decried its estimated $58 million cost as excessive. Executives did not rush to blame the runaway production on their own desire for a summer blockbuster or on the absence of a firm budget until midway through filming. Instead, they pointed to Simpson and Bruckheimer's high-profile life-style, their penchant for converting half a floor of a motel into a personal fitness center (they insisted they paid for it themselves), and their free-spending ways with talent. When the film's earnings began to stall, the studio, according to numerous reports, asked Simpson and Bruckheimer to return some $9 million they'd already earned from Thunder. The duo refused, the visionary alliance unraveled, and they moved on to Disney—where budget-conscious Eisner and Katzenberg are forcing them to make do

with a deal that is said to be the secondrichest in the history of Hollywood.

Wall Street applauded the Simpsonand-Bruckheimer exit, which it viewed as a sacking. "The termination of the multi-year agreement between Paramount and producers Don Simpson and Jerry Bruckheimer is representative of Paramount's renewed focus on reducing production costs," one analyst wrote. "Paramount is rated Buy."

That analyst might have revised his estimate had he known that The Godfather Part III would be a $75 million scramble to meet a Christmas release date; the film was rushed and flawed, and it underperformed. "We went over bud-

The Mancuso-Murphy sit-down was a disaster: the star arrived with his bodyguards, reamed the studio chief out, and left. get because Paramount wanted an early release," Francis Coppola has said. And Coppola believed he knew why: "I think it's because they wanted to sell the studio to a Japanese investor."

Martin Davis will no doubt outlive the flop of Godfather III. The investment guru Mario Gabelli, who owns 6 percent of Paramount's stock, thinks Davis is a godsend. So do the founder's heirs. "During the past eight years, he has more than justified our family's confidence," Dominique and Paul Bluhdorn wrote me. "Martin has positioned the company for the 90s while strengthening those assets which our father cared so much about." A Wall Street sage was more balanced: "Martin Davis is an asshole, but he's an asshole for our times."

At the annual shareholders' meeting, held March 5, Martin Davis was appropriately commanding, charming, even witty—when a shareholder opined that Ghost was a terrible movie, Davis quipped, "I wish all our movies were as bad as Ghost." He did not dwell on the mergers that might have been. Nor did he announce that Paramount Communications was reporting a $7.3 million loss for its first quarter. And with Mancuso sitting behind him on the dais, he certainly didn't say he was hiring Stanley Jaffe.

But, for all Davis's fancy footwork, the wolves may still start to circle Paramount Communications, and the acquisition-minded may remember that for all the money this C.E.O. takes home—and BusinessWeek says he was the seventh-highest-paid executive in America in 1989, earning some $4.1 million in salary and $7.5 million in long-term compensation—he personally owns surprisingly little stock, just 1.8 percent. "In a bear raid, this is a C.E.O. who could find his board turning against him very fast, and he could find himself on the street," a mogul told me.

This scenario had occurred to at least a few shareholders at the annual meeting. "Do we have a poison pill in place to defend the company against a hostile bid?" one asked. Martin Davis wasn't specific, but he hinted that defensive measures had been taken. If so, they may be redundant. For Davis is surely as tough an adversary as he is a boss. In that sense, he may be, all by himself, Paramount's poison pill.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now