Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowAlbania's Reluctant Hero

The revolutionary turmoil engulfing Albania recently forced the exile of its greatest novelist, Ismail Kadare, who for years managed to publish his magically allegorical works under the watchful eye of Enver Hoxha's surreal Stalinist state. Now, while Kadare's critics decry his cat-and-mouse ties to the old regime, his supporters are pushing him to become Albania's Vaclav Havel. JEAN-CHRISTOPHE CASTELLI reports with an exclusive interview from Paris

JEAN-CHRISTOPHE CASTELLI

With the fall of Romania in December 1989, a specter came to disturb the long Stalinist slumber of nearby Albania, rising up from the image of Nicolae Ceausescu's bulletriddled body, crumpled at the base of the execution wall, his red tie crooked like a bloody finger: You will follow, it seemed to threaten the leadership of this most isolated, repressive, and impoverished of countries, and the Communists began to stir uneasily atop an increasingly restive population. Ismail Kadare, Albania's most prominent intellectual and her one writer of international stature, was haunted by a different sort of menace, one which unexpectedly took the avuncular form of Vaclav Havel— President Havel—on whose broad shoulders the mantle of statesmanship seemed tailor-made. This was not, however, Kadare's vision of his own future—and it rapidly became his worst nightmare.

Claude Durand, Kadare's French publisher and close friend, recalls this "Havel Syndrome": "Observers, journalists, diplomats, intellectuals—especially abroad, but also within Albania— began to say, 'A writer-president might be a good idea: is Kadare a Havel, or isn't he?' " Far from flattering Kadare, this kind of speculative halo-fitting placed him in physical danger, without even the fringe benefit of public martyrdom. He had already sent out a barely coded S.O.S. in the guise of a preface to the works of Migjeni, a suppressed Albanian writer from the thirties: "[The writer] knows that he has lost the windfall of imprisonment, that fine old custom, and that, precisely because of his fame (ah yes, how accursed!), he has no other choice than to wait to be dispatched directly underground. All that remains now is to imagine the type of death that the dictatorship is preparing for him: the poison in his cup of coffee, a car accident or the knife of an alleged drunkard in some dark stairwell."

Anything could happen in this sinister comer of the Balkans, and often did. Wedged between Greece and Yugoslavia and only fifty-five miles from the once threatening heel of Italy, Albania (Shqiperi, the Land of Eagles, to its natives) has shrouded itself in such complete isolation for so many years that it feels more remote than, say, Burkina Faso—almost an imaginary country, if anyone could even imagine such a strange and sinister place, where religion was banned (Albania used to be predominantly Muslim), private cars were illegal, foreign credits were prohibited by the constitution, the borders were sealed shut, and some 100,000 bunkers dotted an area not much larger than Massachusetts. Under its paranoid leader, Enver Hoxha (pronounced Ho-ja),

Albania was prepared to take on the entire world if necessary—neither the Soviet Union under Khrushchev nor China after Mao was ideologically pure enough for him, so he broke with both Communist superpowers. "The Albanian people will eat grass rather than renounce their defense of Marxism-Leninism, ' ' wrote Hoxha, and by the time he gave up the ghost, in 1985, the isolated, destitute Albanians (with a per capita annual income under $900) were left with little more than such selffulfilling slogans.

As late as 1990, Hoxha's successors had shown only the faintest stirrings of reform, and cautious proposals by Kadare and other intellectuals had spooked the remaining hard-line elements in the regime. It was Kadare's increasingly vocal denunciations of the Sigurimi, Albania's hated secret police, which earned him their outright enmity; personal contacts with President Ramiz Alia, himself on shaky ground, provided him little protection. After confused but hopeful signals from Alia throughout the spring of 1990, a perceptible hardening of policy set in, followed in July by the unprecedented sight of thousands of young Albanian refugees clambering desperately into foreign embassies. Dark rumors began circulating through the capital of Tirana: Alia's dog had been poisoned as a warning; a list of the country's most prominent intellectuals, with Kadare near the top, had been drawn up...In mid-September 1990, Durand traveled to Albania at his friend's request; the two men went for a walk on the beach, where the sound of the waves could carry Kadare's announcement of his impending exile out to sea, beyond the ears of the Sigurimi.

If there is a legendary dimension to Kadare's fiction, it is absent from his real-life departure—no daredevil swim across the channel to Corfu, dodging sharks and currents and bullets from patrol boats, merely a well-timed invitation to France by his publisher, Fayard, to launch his novel The Palace of Dreams in September. He had hesitated to leave before, out of fear of retaliation

against his family, but in an extraordinary stroke of luck, Kadare managed to send his younger daughter abroad with Durand before his own flight with his wife, Elena, who is also a writer; his older daughter was already in Paris studying biology. His defection was announced on October 25, followed by a declaration to Le Monde that "the promises of democratization are dead," and then Kadare disappeared into anguished seclusion outside of Paris for two months, under police protection.

The country he left behind changed more explosively than he could have imagined. With Albania's first multiparty elections at the end of March and full diplomatic recognition by the U.S. after fifty-two years of bitter estrangement, the black sheep finally seemed to be rejoining the Eastern European flock. But it is the chaotic Romanian—rather than the calmer Czechoslovak—model that continues to loom over the country. In the last two months, clashes between prodemocracy forces and hard-liners have left a number of people dead, and rapidly deteriorating economic conditions caused the small country to hemorrhage population from all sides: across the Yugoslav border to the north, to Greece in the South, and, most spectacularly, across the Adriatic to Italy, where nearly

20,000 young Albanians sailed almost anything that would float. Martial law was declared in several port cities, but it was doubtful to what extent anybody, even Alia, was really in control.

More than at any time in her recent history, Albania needed a moral center. The confused rush of shock, recrimination, sorrow, and support that followed Kadare's exit provided some measure of the enormous void he left behind. "If he had died, we would all be there crying out our pain and praising his qualities," a young writer told the French newspaper Liberation, "but he preferred to leave and so we vent our spleen." Those who could see only the charmed (for Albania) surface of his life—his right to travel, his access to a car, his desirable apartment— reproached him for having been too cautious, too comfortable, for having left Albania in her time of greatest need. Vaclav Havel was a friend of ours, the street seemed to be saying, and, mister, you're no Vaclav Havel...

"It was a black day for Albania when people learned of his exile,'' remembers Sali Berisha, a Tirana cardiologist who became one of the founders of the organized opposition which sprang up in the wake of Kadare's departure. Like most of Kadare's intellectual colleagues, however, Berisha says that he

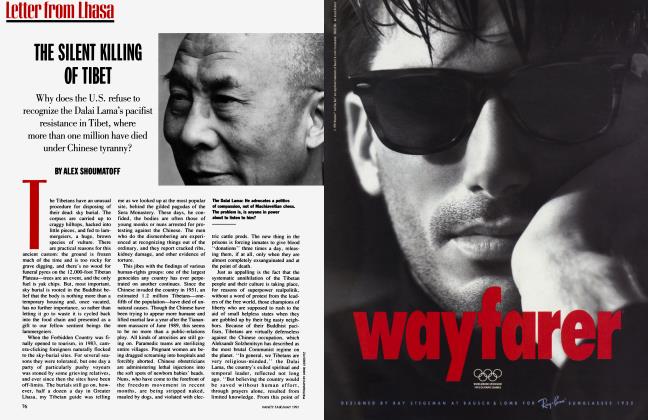

Kadare's vocal denunciations of Albania's hated secret police earned him their outright enmity.

fully understands the novelist's reasons. And like most Albanians, almost without exception, he proclaims, with mingled pride and regret, "Kadare is the genius of our land and our people.''

smail Kadare also happens to be a genius tout court, one of the world's few great living writers. His novels are regularly hailed as major literary events when they come out in France, and while we know better than to trust Frenchmen bearing tribute to other cultures, they are onto something here. On the purely literary level, he has often been compared to Gabriel Garcia Marquez, the slot generally reserved for historically rooted ironists and exotic storytellers with a streak of the fantastic. If Kadare has yet to produce a really "big" book like One Hundred Years of Solitude, his work as a whole stretches magisterially across the peculiar solitude that has cloaked Albania through the five centuries under the crescent moon of Ottoman Islam and well into the enigmatic murk of the post-World War II period. Drawing on the rich oral tradition which for centuries was Albania's main fortification against forgetting, Kadare is above all a singer of tales. He dreams locally and writes globally: on paper, he would be the perfect Nobel candidate for a committee that has tried to recognize at least one writer from every area of the world, no matter how obscure. American readers risk getting caught short, as we usually do— "Naguib who?"—when the time comes.

An independent New York publisher, New Amsterdam Books, has valiantly kept Kadare's name afloat on this side of the Atlantic with a small but representative sampling of his prolific output. This includes a recent reissue of The General of the Dead Army, his first novel, which was translated into more than a dozen languages in the early seventies, single-handedly putting Albanian literature on the world map (and on the screen, in a French-Italian coproduction starring Marcello Mastroianni and Michel Piccoli). The story of an Italian general who returns to Albania after the Second World War to collect the remains of his fallen compatriots, it's a remarkable meditation, both grave and ironic, on the relationship between a country and its former occupier, with echoes from Troy to Kuwait.

Chronicle in Stone, Kadare's most beautifully written work, is an autobiographical novel about his wartime childhood in the southern Albanian town of Gjirokaster. In a rare and welcome descent from the legendary into the intimate, he draws an exquisitely strange portrait of the inanimate world through the animist eyes of a child. ' 'Thoroughly enchanting," commented John Updike in a New Yorker review, and you can see why: Kadare pulls plump metaphors like so many rabbits out of a hat, and boy does he let them run.

Of the novels available in English, the most typical is perhaps Doruntine, which is set in a medieval Albanian town: the young woman of the title marries into a family from a distant country, and her brother Constantine gives his bessa, or sworn word, to his mother that he will bring her back whenever she is needed. Constantine is killed in battle, but when the grieving mother curses her son for not keeping the bessa, Doruntine shows up on her mother's doorstep a few weeks later, claiming that it was indeed her brother who had brought her back. Out of this simple ballad, Kadare fashions a metaphysical detective story, an investigation into the power of a homegrown legend like the bessa to transcend adversity—be it death, foreign occupation, or, by modem extension, the imposition of a foreign ideology by the state—and define the national identity of a people. (This sense of honor was carried to its extreme in the form of the infamous Albanian blood feud, which pervaded the highlands until the Communists took over, part of a rigid, unwritten code of law that stated that even a total stranger spending the night under a man's roof had to be avenged by his host if harm befell him the next day. Kadare describes this machinery of vengeance in a grim and beautifully constructed short novel called Broken April, his chronicle of a death foreordained.)

As Doruntine demonstrates, the storyteller is also a canny political allegorist: when the magic-carpet ride is over, the underside of his work becomes visible, a dangerous weave of innuendo threading its way through the colorful narrative fabric. What is missing from the English-language selection of his novels is how openly daring Kadare could get in some of his later works. The Concert, for example, is a wild modernist romp through the Chinese Cultural Revolution, complete with a Strangelove-Qsque Chairman Mao, who grows vast fields of marijuana in a fiendish plot to destroy the world's culture, a potent metaphor for the kind of doctrinaire extremism—the grass of the intellectuals—that Hoxha himself cultivated for so many years. (William Morrow has acquired both The Concert and The Palace of Dreams, which it plans to publish within a year.)

he physical discrepancy between an author and his body of work could not be more pronounced than in the case of Kadare. The genius of the Land of Eagles shows up to meet me at the Left Bank offices of Fayard on a cold February morning, and he turns out to be a rather short and unprepossessing man, vaguely owlish behind the heavy socialist designer frames of his glasses. His sad eyes and falling cheeks give his face a hopelessly melancholy cast, occasionally broken up by a strangely wide, almost childlike smile. Only the imposing high forehead, curving up like a kind of architectural dome, reminds you that this man is a national monument.

Kadare has only recently emerged from his period of seclusion, but he has not been idle: in little over two months, he has written a book which Fayard rushed into print in late February in both French and Albanian editions. Albanian Spring is at once a chronicle of Kadare's decision to leave and an open meditation on life in a totalitarian regime that he could not have written until now. For years, Kadare figured as the outermost planet of the European literary system, with an elliptical orbit and a surface perpetually shrouded in mist. Furthermore, his friends had described him to me as shy and extremely reticent, "so unmediatique that it becomes touching," an impression borne out by his disastrous 1988 appearance on the French literary talk show Apostrophes, where the increasingly frantic verbal soft-shoe of host Bernard Pivot found little echo in the stone silence of his guest. But writing Albanian Spring appears to have had a cathartic effect on Kadare: he is surprisingly relaxed, almost voluble, with only a slight hand flutter of nervousness to evoke the tremendous pressures of so many years of self-imposed silence and dark, allegorical hints.

Perhaps because we know so little of Albania, Kadare's is certainly one of the more puzzling cases in the long annals of the relationship between the writer and the state: a shifting embrace that is sometimes amorous, sometimes deadly, and often strangely like a tango, with both partners uncertain about who is leading whom. Kadare received a formative lesson in Communist literary politics when, as a young student on literary scholarship at Moscow's Gorky Institute, he was able to witness firsthand the full fury of the Soviet Establishment against the lonely figure of Boris Pasternak for his "counter-revolutionary" novel, Doctor Zhivago. So Kadare never became a dissident except, very reluctantly, in the end. But in such a tightly controlled country as Albania, was open dissent ever an option? To be effective, it would have required an international spotlight, and the curtains were tightly drawn around Albania.

So Kadare, who was bom in 1936 and is therefore almost entirely a product of this dark, carceral theater, went about slowly, carefully cultivating his interior garden. Even in the apparent liberty of Paris, Kadare insists, "I feel that I am not more free, inside of myself, than I was over there." He does not renounce anything he has written, nor does he plan to revise any of his works now that he is out of the country.

Many of Kadare's most daring novels were not only written but actually published "in the worst heart of the dictatorship," as he puts it, a fact that is as much a testament to the strange quirks of Albanian cultural policy as it is to Kadare's stubborn pursuit of—and occasional tactical retreats from—his art. "Censorship did not exist in Albania," he declares flatly, though he qualifies this with talk of "censorship, Mediterranean-style," haggling in the literary bazaar between the author, who could try to push the limits of the acceptable, and the editor, who risked his neck if things went badly afterward, as they often did with Kadare. "My books were banned after publication, like The Palace of Dreams: it was published, sold, and then banned." He laughs derisively. "It's great, that—banning a book afterwards:/"

In a paranoid state like Albania, where until recently tuning in foreign broadcasts could land you in prison, this kind of latitude seems remarkable. Kadare' s international reputation no doubt had something to do with it, but even that was no guarantee: one of the most severe attacks came in 1975, in the midst of a general hardening of cultural policy, when "The Red Pashas," his satirical poem about the bureaucracy, was seen as an incitement to revolt. After that peculiarly socialist form of atonement, the humiliating self-criticism ("I thought that because I was a famous writer everything was permitted, but it's not true and now I understand that nobody can say anything against the state... "), Kadare was sent off to a remote village in central Albania under the watchful eye of a veteran Communist, and allowed to return to Tirana only for his father's funeral. "For a few years I couldn't print anything," Kadare recalls bitterly. "I was known throughout the world, I was published in fifteen countries, and you know, nobody said a word—not a little word, nobody, nobody." It was a chilling lesson: "You could be calmly smothered without anyone helping you or saying anything.

For all that, Albanian writers seemed to have been exempt at least from the harshest penalties that the regime regularly meted out to almost everyone else. He shrugs: "Maybe it was a bit the vanity of Hoxha, who was acquainted with the West and wanted to represent himself as a liberal, as someone not all that hard when it came to culture."

Enver Hoxha, under whom Kadare published most of his important works, was certainly a paradoxical figure in the Eastern bloc: what other hard-line Stalinist could boast a French education and an early career as a lycee instructor? "He knew how to dress well, and had very refined manners," Kadare recalls. "All the other Communist leaders, even the French ones, were so boorish." Shades of the red-faced Khrushchev pounding his shoe on the table? Kadare laughs: "For the Albanians, who have always been a rather elitist people, it counted a great deal."

Even more important was Hoxha's political chutzpah: evincing a strange mixture of cunning self-preservation, rabid nationalism, and ideological paranoia, he managed to cast himself, and Albania, as a sort of heroic David, flinging the hard stones of MarxistLeninist orthodoxy at successively larger and more "deviationist" Goliaths— Yugoslavia in 1948, the Soviet Union in 1961, and China, Albania's only remaining ally, in 1978. Kadare devoted his longest and most complex novels, The Great Winter and The Concert, to these last two defining events in Albania's recent history.

As recounted in The Great Winter, Hoxha emerges from his confrontation with Khrushchev every inch the bronze statue he wanted to be, with a striking profile and a slightly hollow clang. This raises the problematic question of the extent of Kadare's accommodation with the regime, which he dismisses for the most part as merely "socialist courtesy" to avoid unnecessary trouble; the same with his party membership and his brief vice presidency of the Democratic

He dreams locally and writes globally: on paper, Kadare would be the perfect Nobel candidate.

Front, a mass organization devoted to translating party directives into popular action: offers he couldn't refuse. While acknowledging Kadare's literary importance, Arshi Pipa, a literary critic who left Albania in the late fifties, sees The Great Winter as the beginning of a kind of Faustian bargain, morally and artistically fatal: "He had a kind of rebellious rage against the regime, which he expressed in different ways, subtle ways, but once he accepted to play that game, to magnify Hoxha and through magnifying him to accept the regime—the two cannot be separated—then his style declined also. ' ' For Pipa, a longtime veteran of Hoxha's political prisons, Kadare has fallen short of his early promise: "He is a person who wants to live well, he is by nature an aesthete, and he thinks that literature is everything." For his part, Kadare claims that Pipa's articles put him in serious danger by reading into his novels dangerous insinuations about Hoxha's sexuality that he says simply were not there. "You were lost if you said such things," he says angrily. "Pipa was in prison himself—he knew that this was one of the reasons many people were condemned." Kadare's normally gentle tone becomes uncomfortably ad hominem: "I don't forgive this, because he did it on purpose—out of jealousy and nothing else."

Kadare expresses the view that, if dissidence is not an option, the writer can act as a kind of corrective for the totalitarian regime. "You have to find the means of reconciliation," he explains. "So I thought that if you showed a tyrant with a mask which would reform his face, he would then reform himself." Kadare's tone becomes somewhat rueful: "In my novel, Hoxha is shown as a kind who is against repression, and I was sure that he would then be obliged to play that role." To support his thesis, Kadare cites the ancient Greek dramatist Aeschylus and his refusal to take sides between Prometheus and Zeus, though the latter is clearly presented as the tyrant.

Hoxha may have remembered his Aeschylus from his lycee years, but he continued to quote Lenin and Stalin—a kinder, gentler Hoxha never emerged. He spent his twilight years trying to write himself into a kind of fossilized posterity, the Tirana-saurus rex secreting his own tar pit in the form of voluminous memoirs. The early eighties were an especially dangerous time for Kadare, whose growing international reputation landed him in a nightmarish parody of literary rivalry. "What a terrible thing to be a well-known writer in a small country!" he exclaims. "And even more terrible, the head of the country himself is jealous, he wants to be a writer too, so it's finished for you.. .Imagine a Stalin who wanted to be a writer!" (Kadare and Hoxha even shared the same French translator, an elderly Albanian aristocrat named Jusuf Vrioni, who deserves more than a passing tribute for his exquisite rendering of Kadare's prose, which has played no small role in Kadare's success abroad.)

Rather than stimulating extra caution, the political repression of this period found its literary correlative in Kadare's most daring novel, The Palace of Dreams. By any standard, it is one of the most complete visions of totalitarianism ever committed to paper: in a vaguely Ottoman setting—Kafka's Castle with minarets—Kadare constructs the perfect institution of surveillance, a labyrinthine bureaucracy in charge of gathering and interpreting every dream in the far-flung empire. Kadare claims to follow his inspiration, never to write direct allegory: "When it came out I was myself horrified. How had I done this? Because I was always buried in literature, and I did not imagine the danger. ' '

This time the obligatory attacks and self-criticism were followed by something more insidious: "I understood that my life was directly threatened." Kadare pauses; I ask him how, and he shrugs as if it were self-evident (as it is, perhaps, in Albania). "With the most classical methods, and the most dangerous ones. That is, threats by hooligans who would call me and say, for example, 'I am going to kill you'—those kinds of banalities—and would do it repeatedly." A friend who worked in the Ministry of the Interior warned Kadare against reporting these threats to the police: they were in on the game, and making a complaint would only provide an alibi ("Comrade K. wasn't vigilant enough...") if something "unfortunate" did happen.

In assessing Kadare's literary career up to this point, one might quote a passage from his essay on Migjeni, which is surely intended as a kind of self-justification. "Even in dictatorial regimes," Kadare writes, "great works sometimes see the light of day, just as it is thought that diamonds are formed under infernal pressures." Kadare's work certainly was brilliant and multifaceted, (Continued on page 182) (Continued from page 169) but the metaphor goes further than he perhaps intended, for his writing also became one of Albania's most important exports—perhaps not in terms of hard currency (that honor went to chromium), but in terms of prestige. If one ornament dangled from the gargoyle-gray facade of Albanian socialism, Kadare was it. But for Albanian readers, his work also had the hardness and cutting edge of diamond, a guarantee against the numbing language of slogans and party directives.

In fact, the Collected Works of Comrade Enver became a symbolic target of young Albanians' frustration. When Kadare returned in December of 1989 from a visit to Paris, where he had watched with fascination and horror the televised collapse of Ceausescu, one of the first rumors of unrest that reached Kadare was of a bomb that had been placed in the bookstore next to his house, which sold little other than the hated tomes. There were also reports of crowds attempting to tear down statues of Stalin, the last ones left in Europe. At the end of January, the first unofficial mass gathering took place in Tirana's Skanderbeg Square, though no slogans were shouted and no one seemed quite sure what they were doing there. As Kadare describes it, "It was like a halfdream. . .we couldn't understand whether it was really a demonstration or not."

On February 3, 1990, Kadare requested an interview with President Ramiz Alia, and on the next day found himself in the same office where he and other writers had suffered some of their harshest denunciations. Kadare was often aware of the pressures that Alia himself had had to face as the head of propaganda, the man held responsible for a culture which was judged by hard-liners to have "betrayed socialism." Not only did Kadare and Alia have friends in common who had been imprisoned, Alia "was himself menaced by Hoxha several times, he himself faced the tomb. . .he suffered with everybody." Alia weathered the storms and became Hoxha's handpicked successor. Kadare's assessment of Alia is ambivalent but sympathetic: "You have to understand, he was a weak man, but he was not cruel. This was the most important thing. This is why everyone liked him so much, and why he disappointed everyone. They expected so much from him"—to become an Albanian Gorbachev. If the people did eventually get their wish, they also got the bad part of the package: the half-measures and partial power shuffles, the all-too-numerous hesitations and reversals. (Arshi Pipa, who taught the future leader at the Tirana Lyceum in 1943—Albania is a small world indeed—remembers Alia as "a kind person at the time, pretty modest and respectful." He laughs: "I don't remember him being among my brightest students!")

Kadare and Alia spoke for more than three hours, during which Kadare outlined a number of reforms that stopped comfortably short of revolution: improving Albania's dismal human-rights record, allowing peasants to own livestock and private plots, renewing ties with the West, renouncing Stalin, and reopening the churches and mosques. Kadare describes the encounter as "very good, very relaxed," and says that at the end of the session Alia accompanied him to the door and said, simply, "It will be done."

Kadare would like to think that his initiative, along with subsequent interviews in which he made some of these issues public for perhaps the first time, did indeed have an effect: a small number of political prisoners were freed, and cows began to dot the countryside. Alia also dismissed some of the worst offenders in the Sigurimi, whom Kadare had named in a follow-up letter on May 3, but this led to a thinly veiled threat. As Kadare recalls, "They walked out onto the big boulevard, those who had been condemned, and sat in the cafe together with the head of the Sigurimi, to show their solidarity, to say, 'You'll see.' " The intellectuals could sense a power struggle in the upper ranks that spring, the government often giving with one hand and taking away with the other.

His hope that Alia was essentially on their side was shattered on May 21, however, when Kadare received a reply from the president to his May 3 letter. He paints a vivid picture of his wife, Elena, finding him in his study with a look of utter despair, counting the number of times the word "party" was mentioned (twentythree): "Alia's response was completely idiotic," Kadare says, shaking his head. "I was astonished, because he was speaking with me in a different tone, completely changed."

Alia's letter (reprinted in Albanian Spring) upbraided Kadare for never mentioning the party once in his reform proposals, but his praise for the writer was even more appalling: "Your work is devoted to the defense of the fatherland, of its liberty and independence, as well as to the heroic struggle of our Party and comrade Enver Hoxha to preserve our sovereignty." The totalitarian face had remained the same—Kadare was the one being fitted with the mask. "I lost hope," he says, "and I told my wife that evening, 'We have to leave. There's nothing more we can do in this country.' "

Kadare's departure seemed sadly premature in light of what happened soon after he left. On December 11, following three days of anti-government demonstrations, the Central Committee allowed the formation of a political opposition and promised free elections. Stalin's name and symbol were removed from streets and institutions, places of worship were allowed to reopen, and Alia stepped up his efforts to shuffle hard-liners out of his government. Given the formation of a Democratic Party by Kadare's intellectual colleagues Sali Berisha and Gramoz Pashko, a university economist, people began to wonder if Kadare hadn't, in the words of one friend, "missed the boat."

Kadare admits that he hadn't expected things to change so quickly, but he claims that his departure was more than a gesture of despair, that it was precisely intended to shake things up. "If I had stayed I would have been caught up in the whirlwind," he says. "Everyone would have expected something great from me, and what great thing could I have done, throw a bomb in the Central Committee? Now, my departure, that was really like a bomb!"

One of his books, a collection of essays, had already been printed, and the government was forced to release it after failing to mobilize any real popular condemnation. "Everyone understood that this was the first time that the dictatorship accepted somebody who was against it; so they said, Let's go, we can do it, too." From Tirana, Dr. Berisha confirms this: "Nobody has done more than Kadare.

.. .When he left, the level of emotion was so great that he accelerated the process by leaving the country."

Now Kadare hopes to keep the level of emotion down by means of his new book, which returns to the theme of reconciliation again and again like a touchstone: "I want everyone to understand what the gloomy universe they lived in was really like," he says, "to be calm and not tear out each other's eyes, saying, I did more than you, you didn't do anything. Revenge is a terrible thing in the Balkans."

In the last few months, the situation in Albania has become increasingly unstable. The government agreed to postpone the elections until March 31, ostensibly giving time for the opposition to organize, but conservative elements continued to do everything in their power to disrupt this. Student protests flowered into a full-scale popular uprising, with Alia keeping one frantic step ahead of their demands like a kind of political Indiana Jones, caught between a rolling boulder and a hard line. He dissolved most of his presidential council, appointed a caretaker government, and ordered troops and police not to fire on demonstrators. But on February 22 a clash between civilians, police, and members of a Tirana military academy left four dead and rumors of an impending military putsch. One of the hard-liners' main demands, significantly, was the restoration of the Hoxha monuments that the crowds had managed to tear down; the Communists may have taken some consolation in the fact that stone fragments from the toppling forty-foot statue in Tirana's main square injured two people—a symbolic warning of the dangers from loose chips off the old bloc.

In a telephone conversation in February, Dr. Berisha spoke of police roadblocks in remote areas, of beatings and intimidation of members of the opposition, of threats of bloodshed in the party newspaper. "I am worried by the tension, promoted by those who are interested in civil war," he said. "We will do our best to prevent this—we are a democratic party—but there are limited means."

Kadare went as far as to say, "I don't give a great deal of importance to the elections. Rather, the main thing is to avoid anarchy. Because democratization will work very well—no force can stop it except anarchy."

The last time I call Kadare in Paris, he sounds cheerful and quite settled; he even talks, with some pleasure, of looking for his own apartment there, though it is hard to imagine a writer as deeply rooted as Kadare truly thriving in the dry potting soil of French intellectual life. Our conversation is interrupted by a broadcast from Albania, a tinny voice on his shortwave radio, remote but still crying out: Kadare informs me that student demonstrators in Tirana have called a strike, demanding the resignation of the government. "The people can no longer tolerate imbeciles," he observes acerbically. A detail he doesn't mention, one I pick up from the next day's New York Times, is what happened after the rally: the students sang songs with words from works by Kadare and—that name again—Vaclav Havel.

The students' vision of a writer-president has some national precedent as well: Albania's one period of enlightened leadership—all six months of it—occurred in 1924 under Fan Noli, a Harvard-educated archbishop and poet. Kadare points out, lest the parallel become too enticing, that Noli prepared himself for office by rendering Shakespeare's tragedies into Albanian, and brooded after his overthrow by translating Don Quixote. And when I ask him whether he will ever become directly involved in politics, Kadare's response is a vehement "Never!" There is an uncertain laugh. "I feel intuitively that it would be something sinister. . .as if you saw me dressed up as a woman."

Kadare continues to keep a careful distance from events; he never made any promises, after all, that he would be anything more than a writer. Durand speaks glowingly of Kadare's single-minded devotion to his art: "I have encountered this vocation in only one other person: Solzhenitsyn, who has a completely different temperament, but who has the same consciousness of the role of the writer, the will not to let himself be dragged out of his role." Kadare does not, of course, have the prophet motive of Solzhenitsyn, whose novels have become so heavy with historical significance that even the paperback editions feel like stone tablets. And it is unlikely that the Albanian will ever become the velvet messiah—the New Testament model—either.

In his country, Kadare only did what he felt he could practically achieve at the time, no more—and yet history has shown that if actions speak louder than words, literature

often speaks louder than actions. So the Albanians built their hero out of black words on shining white paper—just as, in frustration, they tilted at the ogre embodied in the thick, gray tomes of Hoxha—and they still expected everything from him. It seems that the legend of Doruntine, which Kadare tried to transform into a universal myth, has now acquired a strangely person-

al resonance: the favorite son who departs his world before he can fulfill his promise, the mother who shakes her fist, in rage and despair and hope, at the tomblike door of exile... Perhaps it is Kadare's work as a whole which, by its freedom and power, has become an unbreakable promise, a bessa for a small and forgotten country struggling to find its way out of the shadows.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now