Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowCAMERAS COURAGEOUS

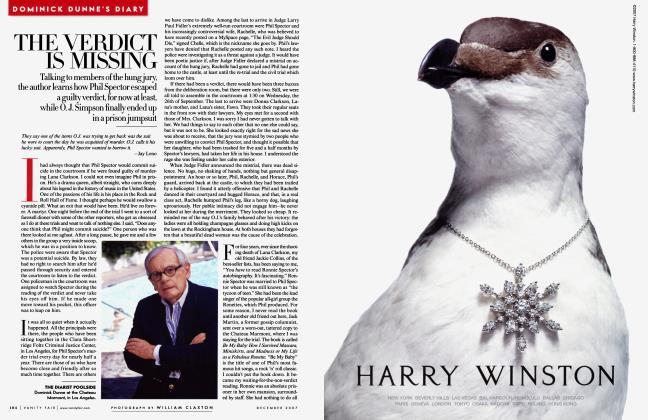

Legendarily fearless A.P. photographer Horst Faas has compiled a book of pictures by colleagues killed in Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos. Due out this month, Requiem is the homage of a man whose luck held to those who never came home

DAVID HALBERSTAM

On the day President Kennedy was assassinated, Horst Faas, the Associated Press photographer, having not yet heard the news, left the small villa he and I shared in Saigon and went to Tan Son Nhut, the main airport of Saigon. He was supposed to get on a Huey early the next morning and fly to the dangerous Camau peninsula to shoot a combat operation. Just before leaving on the mission, as he ate breakfast at 4:30 A.M. Faas learned of the tragedy. He returned immediately to the villa and did not go out in the field for another week. He was not about to risk his life in a shooting war when the rest of the world was transfixed by a story elsewhere, and when no editor in the world was going to use his photos. He would take any risk—and this was to become something of a trademark—save a futile one.

He was distinguished by high ambition and singular toughness from the start. He grew up in Germany, started working for the Associated Press in the late 50s, and made his way to the Congo in 1960 just as it underwent its turbulent separation from colonial Belgium. We met in the Congolese capital, then known as Leopoldville, in July 1961, a few weeks after he had had a legendary confrontation with several Danish U.N. soldiers at a pizzeria there. The Danes apparently took exception to Horst's cameras and profession and started jostling him. His colleague Dennis Neeld, a burly A.P. journalist, intervened and took on four of the Danes. The last thing anyone saw was Neeld going down under the soldiers' blows, with Horst diligently photographing the event.

From the start I loved working with him. Smart, funny, and generous, he was always ready with an epigram. After covering a failed coup by four French generals in Algeria, he told me, "Ah, David, most generals, in civilian clothes they look very small, huh?" Complaining about his wire-service editor's perpetual desire to have a shot of the principals shaking hands at all meetings, he once said to me, "Adenauer lands at Orly. De Gaulle greets him. Adenauer surprises everyone by punching de Gaulle in the nose. I am the only photographer who catches it. That night I get an angry rocket from Associated Press asking me where my handshake photo is."

A.P. (and later CNN) reporter Peter Arnett, who worked with Horst in countless combat situations, believed that he had a sixth sense about a battlefield—where the action was going to come from, where to shoot the pictures from, and, above all, how to survive. Horst was not just a great photographer but a great reporter as well. Whoever debriefed him when he got back from the field was lucky indeed. I realized this very early on, because he helped me enormously in the Congo.

Horst was nothing if not inventive. He used rubber condoms to protect his film from the muck of the Mekong delta. He was the first photographer I ever met who carried dummy rolls of film and hid his good stuff so that if the authorities questioned him he could, with a great show of reluctance, hand over the fake rolls. He was one of the first photographers to use Leicas in Vietnam instead of Rolleis and Speed Graphics. Because the Leica allowed the photographer to look forward instead of down and didn't block the view with the film, it gave a better and somewhat safer view of combat.

In combat situations, he always wisely measured the risks. In the early days in Vietnam, when we went out with South Vietnamese troops, he would carefully observe the weapons and kits of the units he was accompanying in order to find out what might happen if they were hit by the Vietcong. By the end of the war, when the American troops had departed, he kept several hundred dollars carefully hidden away in his knapsack so that if he was wounded he could buy his way out.

During his 12 years in Vietnam, he probably participated in more combat operations than any journalist in history (save, perhaps, his running mate Peter Arnett), and he became something of a legend within the profession. He won the Pulitzer twice, once in 1965 in Vietnam and then in 1972 for photographs of an execution in Bangladesh (with Michel Laurent).

Oddly enough, the American military leadership loved him. The U.S. commander in Vietnam, William Westmoreland, who, to put it mildly, was not fond of Arnett, adored Horst—this brave young foreigner who seemed to spend all his time in the field and whose photos did not seem particularly political. Arnett, often cold-shouldered in the field by Westy, would watch with amusement while the general greeted Horst warmly—apparently ignorant of the fact that many of Arnett's best stories came from Faas.

When Horst arrived in Vietnam in 1962, there was a certain resentment of him, partly because he had replaced Fred Waters, a popular A.P. photographer from the Korean War days, and partly because he was German. Gradually, though, he was accepted and even admired, but admired, I thought, for the wrong reasons—as someone, it was claimed, who loved "the boom-boom of war." I always believed that reputation was dead wrong. Horst was so good because he was tender, and deep down he hated war, forcing himself to be brave only to do a good job.

During 12 years in Vietnam, Faas probably participated in more combat missions than any journalist in history.

There were moments when his sensitivity was revealed. In the early 1960s he trained a young Vietnamese photographer, Huynh Cong La (alias Huynh Thanh My); in 1965, Cong La, then aged 28, was killed photographing in the delta. Horst was devastated, as if he had been personally responsible. After the funeral, Cong La's father asked Horst to hire his younger son. When the 15-year-old arrived the first day, he said, "Associate Press my family now. I stay with you now." Faas took him in, treated him as a son, and let him sleep in the A.P. darkroom. His real name was Huynh Cong Ut, but the Americans called him Nick Ut. Horst and the others trained him, and eventually he became a dazzling A.P. photographer himself; it was his devastating photo of a naked Vietnamese girl running from a napalm attack that won the Pulitzer in 1973.

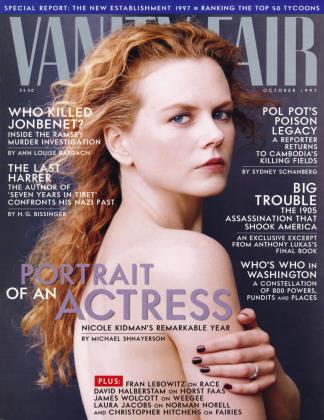

It is the same sense of obligation and duty which drove Horst to compile what will surely be one of the most brilliant photographic books of this fall, Requiem, showcasing the work of all the 135 photographers who were killed or reported missing in both the French and the American Indochina wars.

Requiem is an homage to those who did not come back, by a man who took great risks himself but whose luck held. Horst, along with his colleague the equally fearless British photographer Tim Page, put it together painstakingly over a period of five years, accepting no money for their work. It is an astonishing accomplishment, one which started out as an act of conscience but which has resulted in nothing less than an aesthetic masterpiece.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now