Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

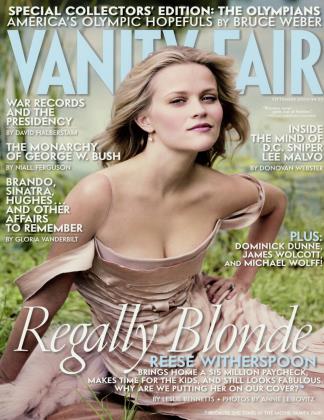

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowDemocrats who fought in Vietnam, such as John Kerry, find their records and allegiance questioned, while Republicans who ducked going (Dick Cheney's deferments, five; John Ashcroft's, seven) pose as macho warriors. Time to look at what combat experience really means—and how patriotism is measured

September 2004 David HalberstamDemocrats who fought in Vietnam, such as John Kerry, find their records and allegiance questioned, while Republicans who ducked going (Dick Cheney's deferments, five; John Ashcroft's, seven) pose as macho warriors. Time to look at what combat experience really means—and how patriotism is measured

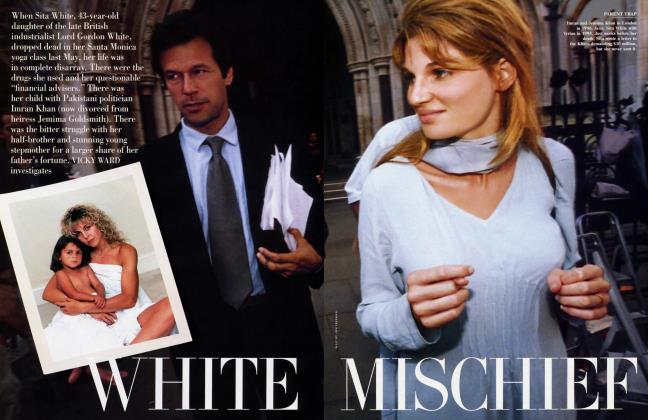

September 2004 David HalberstamWho would have thought that almost 30 years after the last Americans left Saigon we would still be arguing in a presidential campaign about who went to Vietnam and how well they served? But that's the nature of Vietnam—it never really leaves us. It was the second American Civil War, us against ourselves, the blue America against the red America—indeed, one America blue and the other red these days in no small part because of the war; after all, in so many instances it was the children of the red who fought it and the children of the blue who protested it. A comparison with the legacies of other wars is striking and informative; could we have imagined, in 1952, Adlai Stevenson and Dwight Eisenhower arguing over who did or did not serve in World War I, or, in 1976, Ford and Carter challenging each other over who had done what in World War II?

But so it is in this long and increasingly bitter political season that a number of Republican officials have been scrutinizing Senator John Kerry's medals and wounds, wondering whether the latter were deep enough to have justified his three Purple Hearts and whether this is the appropriate time for him to return one or two of them. Maybe I'm missing something, but it seems to me we now have something new, a patriotism fault line running through this country. We require Democrats to work a little harder to prove that they're really patriotic and not somehow in league with our enemies. One would think that deeper war wounds might help, though they did not help Senator Max Cleland, of Georgia, who lost three limbs in Vietnam. When he ran for re-election in 2002 he was found to be inadequately patriotic, and was defeated by a man named Saxby Chambliss, who in the most odious bit of campaigning in recent years ran television commercials connecting Cleland with Osama bin Laden and Saddam Hussein.

These attacks, naturally enough, do not come from Republicans like Arizona's John McCain or the internationalist senator from Nebraska, Chuck Hagel, both of whom served with distinction in Vietnam. If anything, McCain ran into the same kind of attack during the 2000 primaries, when he hit South Carolina and found the head of a Bush-connected national veterans' group challenging his legitimacy as a war hero.

But mostly such challenges seem to come from those who did not quite manage to make it to Vietnam, or Nam, as they sometimes like to call it. (Whenever I am reading a novel with scenes that take place in a country called Nam, I am sure that the writer did not serve in the war there.) Today's leading patriots are, in fact, virtual patriots. For them, words are more important than deeds, and patriotism is an ideologically determined condition. That Vietnam is believed by many who fought there, by most serious historians, and even by some of its original architects to have been the wrong war in the wrong place at the wrong time does not matter to them. In their critique of the war, Vietnam is exempt from its own history. Rather it is the Stallone version: softheaded politicians and journalists, unworthy of America's true spirit, undermined the American effort. The all-important French Indochina War, the eight-year colonial struggle which preceded our war and cast such a powerful shadow over it, is never mentioned by them. The French war meant that we were militarily formidable, but politically crippled from the start, doomed to a war without end, fighting nothing less than the birthrate of the nation, and that our (absolute) military superiority would be matched by their (absolute) political superiority, which in military terms turned into their ability to keep recruiting young men and keep coming at us despite the lethal ferocity of our firepower. This is never mentioned by the hawks; superpatriots need never bow to history.

I cannot imagine this happening at another time: an assault on Kerry and his war record being orchestrated by men and women who did not go, who did not pay that terrible price physically and psychically. But this is clearly a different and more careless America. Reality is ever more fragile these days, placed as it is in the hands of the ever more skillful reality managers of both political parties. Increasingly well financed, they excel at creating a reality that's better and more comforting than the old kind. How else could a president who did not fly in combat during a war when he had the chance choose to imitate a fighter pilot by landing on a carrier in full flight regalia to pose under a triumphant banner reading, MISSION ACCOMPLISHED?

In an earlier America, one that I still remember, if someone had tried a shameless stunt like that it would have been used against him politically. Not anymore: Bush's May 2003 landing on the U.S.S. Abraham Lincoln had the smell of a TV campaign spot all over it (although the sense now that the mission in Iraq has not quite been accomplished has probably dampened the desire to use it as such).

I went to Vietnam for the first time when I was 28. It was the summer of 1962, and 42 years later I am, like so many others, still pondering what happened there, still searching for answers. At the time I was the New York Times correspondent in the Congo, covering the fighting there, but I had wanted the Vietnam assignment, and had been pushing the Times foreign desk relentlessly for six months before my editors said yes.

Why I wanted to go and to go so badly in some ways still eludes me. Perhaps it had something to do with a very ambitious young man's hunger for what was becoming a big story, a prophetic sense that this would be the defining story for a generation (which it turned out to be, though not in the way that I had originally imagined). Perhaps it was a desire to deal with the challenge and test of battle or an emotional wrestling with the shadow of my father, who had served in World War I as a medic and in World War II, at age 45, as a surgeon. All those complicated components of ambition and honor and vainglory are still difficult for me to separate. Did I go for the right reasons or for the wrong? I will never know. Were there, for that matter, right and wrong reasons? Who will ever know?

I am all too aware, as are most of the journalists who went to Vietnam, that there was a quantum difference between being a correspondent, no matter how brave and aggressive, and being a soldier. Correspondents often volunteered to go along on the most dangerous of operations, but they were secure in the knowledge that whenever they wanted they could go back to Saigon or even to the United States. I went out on operations as aggressively as I could, and in so doing I never felt courageous. I was always scared. I returned from Vietnam believing that no one understood very much about the nature of courage as it existed in others, let alone as it existed in himself.

The patriotism debate now going on has unusual resonance for me, because I was one of the first to have his patriotism challenged for raising questions about Vietnam. Very early on I became a target of the war's supporters in the White House, in the Pentagon (which had lots of powerful publicity machinery to use against wayward reporters), and among hawkish journalists, because of my pessimistic reporting. For that reason I made it a point to go out on at least one and, if possible, two combat operations a week. I had to prove that my reporting was not the product of Saigon armchair overview. It was a point of personal honor. I felt I owed nothing less to my readers, to my editors, and to my own family. The distortion of who I was and what I was doing was quite staggering. President Kennedy asked the publisher of the Times to pull me from Saigon, and Lyndon Johnson referred to my talented young colleague Neil Sheehan and me as traitors to our country. As most of the attacks on Senator Kerry have come from people who never set foot in Vietnam, so in those days most of the attacks on me and my colleagues—cruel, dishonest, and stunningly personal—came from people in air-conditioned offices in Washington and Saigon, REMFS, my friend the writer John Gregory Dunne later called them—a term I did not know at the time. It stands for "rear-echelon motherfuckers."

Kerry went from gung-ho optimist, newly arrived officer, to an ever more skeptical and alienated dissident.

Finding out the truth from other Americans engaged in a bitter war was never that hard; hiding the truth is always a great deal harder than telling it. The sources we journalists used were the senior American advisers in the field, and they were far more eager to tell their truths to the M.A.C.V. (Military Assistance Command, Vietnam) and Washington than to a bunch of young reporters. But from the beginning the administration, for domestic political reasons, wanted only to suppress the truth; it wanted to find out who was talking to reporters and then threaten them with court-martial. The irony was that our sources were motivated by the deepest kind of patriotism. Mine included three senior division advisers, two corps advisers, one assistant corps adviser, and one senior two-star American general, whose specialty was counterinsurgency. There was also one close friend, Major Ivan Slavich, the commander of the first armed helicopter company in Vietnam, who took me and Neil Sheehan on any operation we wanted to join.

In Vietnam, the journalists were accused of minimizing the success that the Americans were grinding out, of downplaying the effectiveness of the overall American operation, and of seizing on small defeats to undermine the war effort. The irony of this, in retrospect, I believe, is that our reporting overestimated the strength of the Americans—which was military—and underestimated the long-range military importance of the political superiority of the other side. This was especially true of television journalism, because its cameras instinctively reflected what the Americans did best—gunships roaring into combat areas, unleashing awesome firepower, for instance—but they had no capacity at all to report on what the other side did best, which was to keep recruiting after the Americans had left a village on a given day, to keep coming down the trails at night, and to build their remarkable underground network of tunnels. The enemy's strength, its resilience, its political superiority, and the fact that it controlled the rate of the war simply did not photograph well. The best of the military men there knew what was happening, knew that it was not going well, that we had not dented the other side's dynamic, and that we were fighting the birthrate of the country.

What we reporters wrote then and what the senior military men would later write in their memoirs were strikingly similar. That is notably true of My American Journey, General Colin Powell's 1995 memoir. Powell's views were codified in the Powell Doctrine of the late 80s and 90s. It put the government on notice that the military did not want to be misused again, that the politicians were to think out fully any prospective war, to recognize the proper use of American power, and to clearly commit to using adequate force levels. It called for real allies, genuine domestic support, and, more than anything else, a clear exit strategy. Of course, many of the more hawkish civilians in the Defense Department, the White House, and the National Security Council (and now also in the office of the vice president) were irritated and thought him a wimp. Indeed, in recent years, these civilians have come to see the uniformed military—especially the Army and the Marines, because of their cautiousness, a cautiousness engendered by actual combat in politically hostile climes—as the ally of the more dovish State Department.

I realize that there are vast differences between Vietnam and Iraq, but some aspects are parallel. There is the underestimation of the importance of the colonial past, the overestimation of the legitimacy and validity of our alleged indigenous allies (the foreign leaders we choose in situations like this tend to meet our standards, not those of their fellow countrymen), and a significant underestimation of the political forces aligned against us. If it's right for America, it must be right for others as well, and we'll find someone out there sooner or later who agrees with us. That is, I think, true of us now more than ever in our post-Cold War triumphalism; the State Department's influence has steadily decreased in recent years because it has the melancholy duty to speak for the complexity of the rest of the world in a bureaucracy of powerful men and women who not only are filled with American certitudes but in fact have succeeded precisely because of such certitude.

In Iraq, as in Vietnam, there is no separation between military events and political events—one category merges into the other. As in Vietnam, we are talking hearts and minds, but always thinking military—it's what we do best. By contrast, the other side in Vietnam—and, I fear, today in Iraq—thought first and foremost politically, and then proceeded militarily. For these reasons I think the larger politics of the current struggle are unnerving.

The irony is that Vietnam would come to haunt not one but now two generations of American politicians. This became clear on a day, some 16 years ago, when Dan Quayle became the Republican nominee for vice president and was found, though abundantly hawkish, to have sat out the war in the Indiana National Guard. His spot there had been arranged through the good offices of the Guard's retired commanding general, who happened to work for the newspapers owned by the Pulliam family, of which Quayle was a member. There was a certain sweet innocence to Quayle back then—it was as if the question of going to Vietnam had never occurred to him before, and he seemed absolutely astonished that anyone would try to connect his hawkish political positions with his personal choices. He had a deer-in-the-headlights look when first he answered questions about his military service and said quite candidly that one of the reasons he had not gone was that he had never thought he would be nominated for vice president. In so doing Quayle had involuntarily focused a light on the great political secret of his generation.

Who is a patriot today—someone who immediately puts a small American flag in his lapel, but sacrifices nothing in his own lifestyle, or someone without a pin, but who favors a dollar-a-gallon gas tax, because in the long run that will make us less dependent on a volatile, essentially hostile part of the world? Maybe they're both patriots, for who will ever know? The truth is that the nature of patriotism changed dramatically in the years after World War II. Because we had the atomic weapon, America seemed invulnerable to foreign occupation. Its wars were now less about survival than about something abstract like collective security (Korea), or something which was quite possibly politically dubious (Vietnam). The path for the ascending governing class was now paved with easily attainable deferments.

The new post-A-bomb definition of patriotism was suddenly very different. The children of those who had volunteered immediately for World War II found no compelling reason to sign on for these new wars. Others could go in their place. This was true across the board politically, left and right. But profound changes were taking place in American politics—the Democrats, the party that had given us the architects of Vietnam, now produced its leading dissenters. For the Republicans, it was like getting a bye. Meanwhile, for a variety of complex reasons—economic, social, and demographic—the country was moving right, and a curious demonization of the 60s was taking place. Though two citizen movements of the 60s—the civil-rights movement and the anti-war movement—represented, I believe, citizen politics at its best, they were vilified in the tidal change of American politics. Both movements might have taken place at the very center of American life, but the poster boy for the 60s was now a stoned hippie at Woodstock. A vacuum had been created, and the new Republican Party rushed into it.

The new, modern Republican Party that emerged in that era had powerful roots in the post-civil rights South, among those disaffected by the Kennedy-Johnson leadership on civil rights. The new Republican Party rising out of the Sunbelt was hawkish on defense, wary of civil-rights activism, and retroactively hawkish on Vietnam, even if few of its leaders had actually served. All of this is important, because it casts a very different light upon the two main candidates in this election and how they responded to one of the most difficult and contentious periods in American political life.

I should point out that the patriotic fault line is on occasion nonpartisan, although always ideological: the hard-liners and the neocons, who always seem to know who is a patriot and who is not, were convinced that Ronald Reagan, who did not serve in World War II, except to make propaganda movies in Hollywood, was a war hero, whereas the more moderate George H. W. Bush, who had signed up as a naval pilot on the day of his 18th birthday, was, as a Newsweek cover story suggested, always associated with the Wimp Factor. (Most of the Newsweek editors, as I pointed out in one of my books, had never heard a shot fired in anger.)

To my mind the original point man for the new superhawks, whose words are greater than their deeds, was Newt Gingrich: he became the leader of a new generation of Republican conservatives, who praised the cause of Vietnam and who were steadfast in attacking those who felt it was a terrible miscalculation. But Newt, like many of the other new superhawks, never went himself. (He used to brag that his stepfather had fought in Korea and Vietnam.) My friend the columnist Mark Shields, one of the few men in the media who take this kind of contradiction between words and deeds seriously, asked Gingrich, when he was just emerging as an important political figure, if he had ever visited the Vietnam memorial. He had not, Gingrich answered, which surprised Shields. Did he know anyone who had lost his life over there? No, Gingrich said, he did not—an answer that surprised Shields even more. A few days later Shields approached Al Gore, then a senator. Had he visited the memorial? Yes. Why had he gone to Vietnam in the first place? Because if he had not gone he would have known the boys from his hometown of Carthage, Tennessee, who had gone in his place. Did anyone you know die there? Yes, Gore answered, and he gave several names of Smith County boys. Shields checked out the names, and Gore had been right on each one.

To the new superhawks an America engaged in a worthy war of self-defense and a neo-imperial America engaged in a war that is a significant miscalculation of policy are the same thing. For them there is no right of dissent, no right to change your mind and protest a war, to say that your early support was based on inadequate evidence and the government's manipulation of the sacred trust between it and its citizens. The superhawks' prototype is no longer Gingrich, now retired to the vastly more profitable world of lecturing and writing bad novels. Their new poster boy is the vice president himself, a man of great certitude, not just about Vietnam but about Iraq as well—his confidence and certitude hardly born of a life experience.

Richard Cheney received five—yes, five—deferments, a record that would make most men modest about speaking out on Vietnam and related subjects. He had not gone to Vietnam himself, he once famously told The Washington Post, because "I had other priorities." His confidence in the wisdom of the Vietnam War, however, remains unshakable. It was, he has said, a noble cause.

I think at some point in his campaign Kerry might want to give one speech in which he does nothing but mention six dates: February 1962; March 20, 1963; July 23, 1963; October 14, 1964; November 1, 1965; and January 19, 1966. The first of those dates is when Richard Cheney, then 21 and a student about to depart Yale because he was not doing well academically, received his 1A classification; the next five are the dates of his applications for continuing deferments.

John Gregory Dunne, a student of what I call sunshine patriotism—that is, patriotism with deferments—pointed out that the deferment king was not, as most would have it, Cheney, but that singular American patriot, Attorney General John Ashcroft, who got seven. Yes, seven. Ashcroft graduated from Yale in 1964, an interesting moment because it was one year ahead of the decision to send combat troops to Vietnam.

It is not that Bush did not go to Vietnam that is so bothersome; it is his lack of caring about the lessons learned there.

In the end the most serious question here, as the debate escalates about Bush's attendance record in the Texas Air National Guard and the depth of Kerry's wounds and the disposition of his medals, is whether any of this really matters. Does it matter which of our politicians served in Vietnam or in any other war? Does it make them better public servants? Is John Kerry a better American than George Bush because he went to Vietnam? I doubt it. Is he braver? I don't know.

But going often changes you as a man; even as you're exhausted, you deal with terrifying crises under combat conditions, with the lives of other men hanging in the balance. Harry Truman served with distinction with an artillery unit of the Missouri National Guard during World War I, and it was a turning point in his life, the first thing he had ever succeeded at. Jack Kennedy had always lived somewhat in the shadow of his older brother, Joe junior, but when his P.T. boat was sunk, he found the inner strength not just to endure but to think and act clearly. What he took away from those days in the Pacific, I suspect, was the sense that there was more to him than he might previously have imagined. More, he had won the open admiration of the men who served under him and whose lives he might not have touched in normal times.

Here is where it seems to matter a great deal whether Bush or Kerry went. Vietnam was not an abstract event. It was not a book or a movie, or a briefing card held up to you in the middle of a political campaign by some shrewd adviser who always knows the answers, has the latest polls, and is busy showing an ambitious candidate how to avoid potential pitfalls, as if the presidency were not a place where the daily routine contains potential pitfalls. Vietnam was a critical part of a generation's education. We had entered in the embers of a colonial war, and we had applied our power where it was not applicable. For so many who went it was an unusually painful experience, and what we learned was bitter stuff, not just about our own country, but about ourselves, and it meant a difficult recalibration of many of the ideas which had been at the core of our beliefs. The question for so many of us as we departed Vietnam was a simple one: How could this have happened? I wrote The Best and the Brightest because I needed to have the answer, first and foremost, for myself.

We who went to Vietnam left behind certain prideful things, and came away with a respect for the complexity of the world, one not seen through the prism of what we in America would like it to be. The most interesting aspect of Tour of Duty, the recent book that Douglas Brinkley wrote with John Kerry, using Kerry's tapes, journals, and letters from Vietnam, is the change in Kerry's voice—the sad, gradual maturation process as Kerry, the relatively rare son of the blue America who served, goes from gung-ho optimist, newly arrived officer, to an ever more skeptical and alienated dissident. This was a process I and others witnessed again and again among officers we knew in Vietnam. A friend called me when a chunk of Brinkley's book was published in The Atlantic Monthly. Take out the name Kerry and substitute the names of half the men we knew in Vietnam, he suggested—it's the story of the entire generation that went.

The duty Kerry drew—commanding two Swift boats in the Mekong Delta—was among the more dangerous that existed in country. I would put it right under that of helicopter pilots who went into hot L.Z.'s to take out the wounded and on a level with being a platoon leader. With thick mangroves blocking visibility, every bend in the river was the perfect place for an ambush. That Kerry carried out his assignment well, that he was very brave, that he was admired by his crew, that his superiors were impressed by him are beyond doubt. I have no problem whether or not he threw away his medals at a war protest in Washington, D.C.—if he is now judged, more than 30 years after the fact, to have reacted too emotionally, he had his reasons. The more he and others found out about the war, the more they realized they had been lied to. That would tend to make you emotional. I found then and I still find his testimony before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee impressive for someone so young. I am still haunted by that brilliant, poetic line of his: "How do you ask a man to be the last man to die for a mistake?"

I suspect that the great majority of Vietnam veterans will understand who he is and what he did and why he did it. The attempt to portray him as some kind of Jane Fonda-like figure—a continuation of the 60s-demonization process that has gone on for some 40 years—is, I think, a huge mistake. If Kerry is not as nuanced a politician as Clinton, he is nonetheless less of a target as a figure of the 60s: he represents, as Clinton had not, the complexity and ambiguity of the period, the valor as well as the doubts.

In the case of President Bush, it is not the fact that he did not go that is so bothersome; it is his lack of curiosity about Vietnam, his lack of caring about what the lessons learned there really were. True, Bush cannot be demonized as a figure of the 60s. He was not a part of the 60s. He went to college in those years, but seems completely untouched by the turmoil surrounding him and his generation then—he was oddly apolitical in tempestuous times.

He seems, however, most dangerously, filled with the kind of certitude—indeed, righteousness—about America's course that proved so damaging in Vietnam. When asked by the journalist Bob Woodward whether he had consulted about occupying Iraq with his father, who had prosecuted the first Gulf war so skillfully, he replied that he had consulted with a higher father. But the other side has a higher father, too—and having a higher father does not really get the job done. It's like the football team praying for victory before the big game—that's fine, but don't forget that the other team can pray for victory, too.

When the president has talked in the past about Vietnam, it has been with the most casual of throwaway lines: Well, that was a war, he has said, in which the politicians did not let the generals do what they wanted. That is the shallowest of answers. What worked against the American commitment in Vietnam was not the inadequacy of its military force and manpower—we had 500,000 troops and employed the heaviest bombing in the history of warfare—but the indigenous political undertow, which undermined and essentially stalemated it. That should have had more than a little relevance when it came to thinking about sending American troops to Iraq.

So, I think it does matter whether the president, or, in this case, the vice president, who was so instrumental in the Iraq decisionmaking process, went to Vietnam. I have come to believe that if those who went paid a price, then those who did not go and who did not learn to factor in the complexity of that struggle have paid a price as well, albeit of a different kind, in the gaps in their knowledge. Had they gone and served, I think, they would have been more skeptical about the consequences of invading Iraq and the idea that we would be greeted as liberators there.

What we want—need—from our leaders more than anything else is wisdom, and wisdom normally connotes a slow learning curve, and is usually purchased at a steep cost, the product of having experienced bitter disappointments and failures. My favorite story in The Best and the Brightest—and that of countless readers—is of Lyndon Johnson returning to talk to his great mentor, Speaker of the House Sam Rayburn, after attending his first Kennedy Cabinet meeting. Johnson had been quite dazzled by those in the room— Dean Rusk, Mac Bundy, and Max Taylor. But the smartest one of all, he told Rayburn, was the fellow with the Stacomb on his hair who had run the Ford Motor Company, McNamara. "Well, Lyndon," Rayburn said, "you may be right ... but I'd feel a whole lot better about them if just one of them had run for sheriff once."

Let me add something to that. The most honored decoration for an ordinary infantryman is a badge you get after a certain number of days fighting in the line—the Combat Infantryman's Badge, or, as it's known, the C.I.B. Many grunts I've known who have been awarded a good many other medals prefer to wear only the C.I.B. What it says, to those who matter to them, is that the bearer was there, did it, paid the price. And that's all you need to know.

I know that Dick Cheney is a shrewd and able man and that almost no one, not even Don Rumsfeld, is more skillful at operating in a bureaucracy, but I am inclined to think there is a terrible gap in his education, and I wish dearly that he had gotten one less deferment, had gone to Vietnam, had earned the C.I.B., and had used his high intelligence to learn about Vietnam as he seems to have learned about working in a bureaucracy. I think we'd all be better off for it.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now