Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowA MILLION-DOLLAR THRILLER

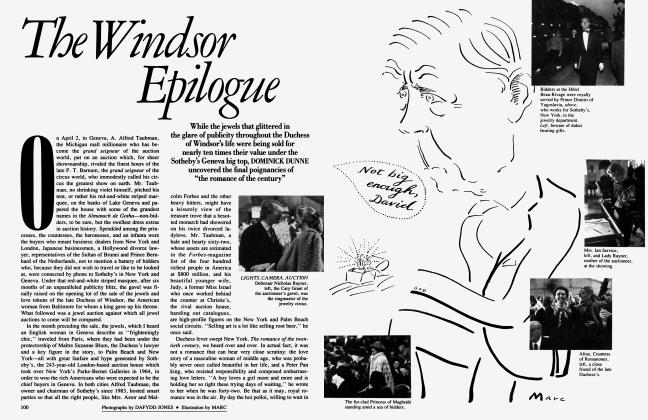

JAMES ATLAS

A Chicago lawyer's first novel is the year's blockbuster crime read

Book Marks

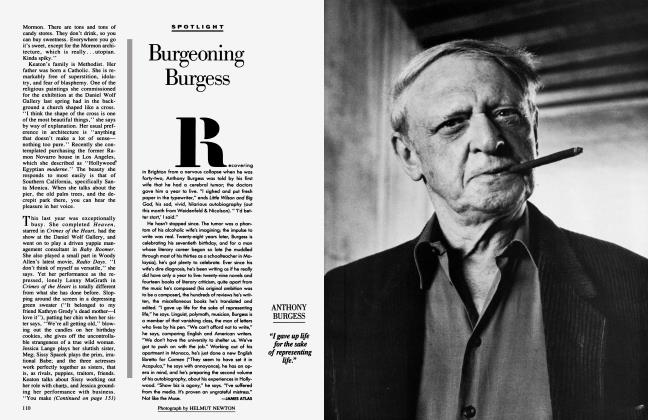

Presumed Innocent wasn't the kind of book Farrar, Straus and Giroux is known for publishing. It was a courtroom thriller, its author a young Chicago lawyer named Scott Turow. Farrar, Straus is a literary house—the most literary trade house in America. Yet there the brown box was, on the desk of executive editor Jonathan Galassi, who had been at his new job for a month. Galassi was just back from jury duty—perhaps that was an omen. He had also written an admiring rejection letter of an earlier novella by Turow that never got published. This new manuscript was bulky. He opened it and started reading.

Thrillers have never been Galassi's thing. He is as highbrow in his tastes as any editor at Farrar. Straus. At Random House he'd published a translation of Rilke, Janet Flanner's Darlinghissima: Letters to a Friend, and T. Gertler's gossipy novel about the New York literary world, Elbowing the Seducer. He himself is known as the translator of the Italian poet Eugenio Montale. Tall, lanky, owlishly bespectacled, he's the kind of person who might have taught your Wallace Stevens class. He fit right in at the publisher of Derek Walcott, Joseph Brodsky, and the late Robert Lowell. His mandate was to go on doing exactly what he'd done in his six years at Random House. No one had directed him to find blockbusters.

But Turow's novel was undeniably compelling—so much so that Galassi decided to push for it. "I knew right away that it was very commercial."

So did everyone else who saw the manuscript that week. Turow's agent, Gail Hochman of Brandt & Brandt, had submitted it to five houses; four of them made bids. The numbers began at six figures—which ordinarily would have put Farrar, Straus out of the running. ''We've been in similar ballparks," says Roger Straus, referring to Tom Wolfe and Philip Roth. But hefty advances aren't Straus's style. Neither are fancy quarters. Housed in shabby offices on Union Square, Farrar, Straus has managed to keep Alexander Solzhenitsyn, Isaac Bashevis Singer, Walker Percy, Susan Sontag, and a lot of other big names on its list by making the company a writers' house, an informal but elite community. Straus has never gone after best-sellers; if they happen, they happen.

For Turow's book, Straus agreed to stay in the bidding, but he was reluctant to go over $150,000. Ned Chase, a senior editor at Macmillan/Scribners, offered $275,000—and was prepared to go higher. ''Everyone wanted this book," he says. Farrar, Straus's final offer was considerably less: $200,000. "I may have to take an extra Seconal," Straus told Galassi, consenting to the bid.

''I was sitting there on the couch at home in Wilmette contemplating all these offers and wondering what to do," Turow recalls. "I'd always wanted to be a Farrar, Straus and Giroux author. My wife said, 'This is what you've dreamed of, so why not have your dream? Forget the money.' " The next morning Hochman called Galassi at home. Turow was ready to go into final negotiations with Farrar, Straus.

It was a dream that had been long deferred. As a Writing Fellow at Stanford during the early seventies, Turow spent four years working on a novel set in Chicago "about a disaffected former draft dodger at the bottom of a youthful depression who's revivified by a rent strike." It made the rounds of publishers, and was turned down everywhere, including Farrar, Straus. "I never counted up the rejection letters." He received enough to make any aspiring novelist lose heart. A year later, Turow enrolled at Harvard Law School.

Obsessively thorough and well organized, Turow couldn't find anything to read that might prepare him for the ordeal of law school. There ought to be a book on the subject, he wrote Elizabeth McKee, who had been the agent for his first novel. "It was a suggestion," he says now. "It wasn't, like, I'll do it." McKee showed the letter to Ned Chase, then an editor at G. P. Putnam's Sons, over lunch. "I can just see her fishing the letter out of her bag" is the way Turow imagines it. Virtually the next day a modest contract from Putnam's was in the mail: $1,000 on signing, $3,000 more upon acceptance of the manuscript.

One L, the book that came out of Chase's lunch with McKee, was a critical and popular success. It sold over a hundred thousand copies in paperback; a decade later, it's still in demand, especially around Harvard Square. Turow's "composite portraits" of his bumed-out professors and compulsive, grade-obsessed classmates—the trendy student radical espousing his "dime-store Marxism," the brutal contracts professor who interrogates students in a "sharply rising, stabbing voice"—were clearly recognizable to anyone who'd gone to Harvard Law. Not that Turow spared himself. He emerges from the pages of One L as driven, insomniac, aggressive. He challenges professors, stays up all night cramming, brings a virtual canteen of supplies to exams. Debating with his study group whether to share outlines as exams draw near, Turow blurts out, "I want the advantage. I want the competitive advantage. I don't give a damn about anybody else. I want to do better than they."

Turow did do better. After an internship in the Boston district attorney's office during his last term at Harvard, he was offered a position with the U.S. attorney's office in Chicago. One of his first major cases was against Illinois Attorney General William Scott—convicted on a tax-fraud charge while he was in office. Another case—an investigation of the Cook County Board of Tax Appeals—led to the conviction of twentysix people on charges of mail fraud and racketeering. Then there was Operation Grey lord, which resulted in the indictment of ten judges on charges of racketeering, extortion, and mail fraud. "He's thorough, he's fair, he's unrelenting," says a lawyer who opposed Turow in two Board of Tax Appeals cases. "You wouldn't want him investigating you."

Turow was working incredibly long hours, but he never gave up writing. In the evenings, on weekends, on his morning train ride into the city, he was at work on a novel. A hundred pages into a draft of what would become Presumed Innocent, he began a novella about two couples, college classmates in the 1960s, who have an encounter in the 1980s. "It was a reflection on coming to the middle of life, and what it felt like to get there." Turow submitted the novella to Hochman, who had worked on One L as an editorial assistant at G. P. Putnam's Sons; she showed it to several editors, among them Galassi, then at Random House. "I thought the material was wonderful," he remembers, "but it wasn't successfully resolved. It needed work." Turow agreed. (So did early readers at Farrar, Straus, who passed up a second opportunity to get him on the house's fiction list.) "I threw it back in the drawer and started over again on Presumed Innocent. ' '

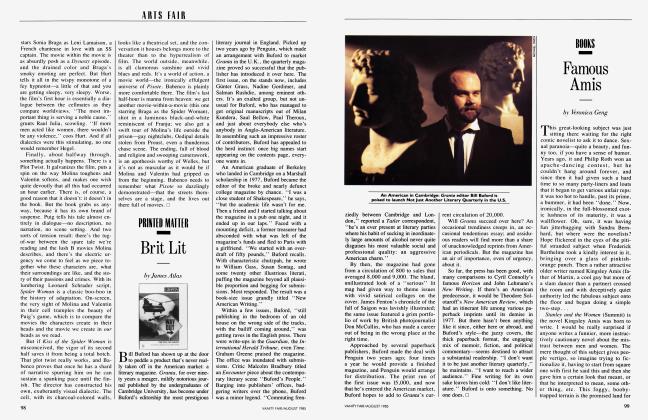

Presumed Innocent has been the talk of publishing circles for months. Sydney Pollack paid a million dollars for the movie rights

After two disappointments, Turow was wary about expecting too much. But he'd worked on the new novel for seven years, and it felt right. "My only concern was that it might be too literary for a whodunit and too much of a whodunit for the literary world."

Presumed Innocent is much more than a whodunit. It's really a book about what happens when everything falls apart. The story of a public prosecutor in a big midwestem city who investigates the killing of a woman attorney with whom he's had an affair and finds himself accused of the murder, it has all the suspense, the heightened pace, the dropped hints and ambiguities of a mystery. The intricate narrative is full of lore about trials and evidence and police procedures. Memorable players crowd Turow's pages. Tommy Molto, the deputy prosecuting attorney, "forty or fifty pounds overweight, badly pockmarked, nails bitten to the quick," a former seminarian who's gone to seed; the lawyer Sandy Stem, smooth, elegant, imbued with "a formal presence that lies over him like brocaded drapes"; Judge Larren Lyttle, a magisterial black whose elaborate good manners disguise a corrupted soul; minor witnesses, stenographers, court reporters, cops: they live. Everything Turow learned in his eight years as an assistant U.S. attorney is in this book. His cynicism is vindicated by experience.

Turow's protagonist, Rusty Sabich, is self-assured, articulate; he's married, a devoted father, on his way to a distinguished career in public service—a character more out of John le Carre than out of Elmore Leonard. (Maybe this is a Farrar, Straus book after all.) You can detect in him elements

of the compulsive, overachieving law student in One L. Surrounded by bribehungry lawyers and time-serving bureaucrats, pasty clerks and cops with fat stomachs, the well-tailored Sabich stands out as "the perfect yuppie"—which is what a Chicago columnist once called Turow, deriding his "lifelong background of silver-spoon living and Ivy League schools."

Like Sabich, Turow is up for judgment. On the accounting side, the verdict is in: Presumed Innocent has been the talk of publishing circles for months. It's a Dual Main Selection of the Literary Guild. There's a paperback floor of $670,000. Foreign rights have been sold in thirteen countries. After a heated bidding war with several major studios, Sydney Pollack paid a million dollars for the movie rights. "The whole thing has an air of unreality about it," Turow said. We were talking on the phone one afternoon; his wife was about to deliver a baby. "There's a very real level on which this has not sunk in. What I wanted to happen most of my life has happened." Was he surprised? "I didn't expect the dam to burst. But it hasn't altered my self-conception."

Even with the immense success of his novel, he doesn't intend to become a full-time writer. After nearly a decade as an assistant U.S. attorney, he's joined a private firm, doing the kind of criminal and general civil litigation work that could well pit him against the federal office he served with such distinction. (Turow's new firm, Sonnenschein Carlin Nath & Rosenthal, represented one of the immunized witnesses in Turow's last big case.) "I like being a lawyer," he says simply. "It's given me a great subject. I'll be very disappointed if I'm not practicing law ten years from now." Meanwhile, he's at work on a new book—"in the gardening phase." What's it about? "Lawyers."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now