Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

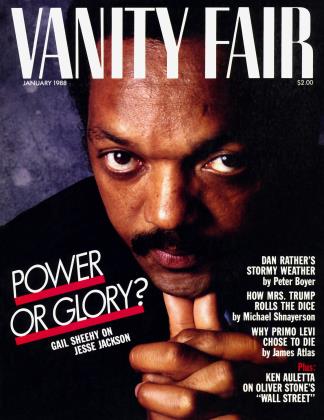

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe Survivor's Suicide

He survived Auschwitz, and bore witness to the Holocaust in his critically acclaimed books, so why did Primo Levi suddenly decide to end his own life last year by throwing himself down the stairwell of his Turin apartment building? JAMES ATLAS went to Italy to talk to Levi's friends in his search for clues

In the spring of 1987, Primo Levi's literary reputation had never been higher. All over the world, translators were preparing his work for publication. There were even rumors that he might win a Nobel. "You'd better get ready to travel again,'' Levi's publisher teased him over the phone on Friday, April 10. "And this time you're going to Stockholm.''

Around ten o'clock the next morning, Iolanda Gasperi, the concierge of Levi's building, at 75 Corso Re Umberto in Turin, rang the bell of his _fourth-floor flat and handed him the mail. "Dr. Levi had a tired look,'' she recalled, "but that was nothing unusual. He was gentle. He took the mail, a few newspapers and some advertising brochures, and greeted me cordially.''

A few minutes later, she heard a loud thud in the stairwell and rushed out of her lodge. "A poor man was lying crushed on the floor. The blood hid his face. I looked at him and—my God, that man!—I recognized him right away. It was Dr. Levi."

Lucia Morpurgo, Levi's wife of forty years, had been out shopping. Her arms were full of groceries as she pushed open the glass door. The concierge tried to hold her back, but she flung herself down beside her husband and tried to lift his head. Their son, Renzo, had also heard the commotion and hurried down the wide staircase. They were joined by Francesco Quaglia, a dentist who had known Levi since high school and had an office in the building. Levi's wife embraced him. "Era demoralizzato," she said tearfully. "He was demoralized. You knew it, too, didn't you?"

urin is a beautiful, somewhat melancholy city in the northwest comer of Italy, not far from the French border. Once the residence of the royal family, it has a faded stateliness that reflects its history: grand piazzas with shuttered windows and cream-colored walls reminiscent of the Place des Vosges; elegant archways and arcades; wide boulevards where narrow orange trams clatter beneath the dusty trees. At night, the air is suffused with a gritty yellowish fog; the streets are clogged with traffic. In the distance, you can see the lovely hills of the Valle d'Aosta on the far side of the river Po, which divides the town. Since Fiat established its factories here, Turin has become an industrial city, poor in the suburbs and prosperous in the center, but it still possesses the sad, provincial character evoked in the poems of Cesare Pavese, the famous editor and writer who lived in Turin nearly all his life and committed suicide here in 1950. Looking out the window of my hotel room the night I arrived, watching the shop owners pull down their shutters, the waiters stacking chairs, I recalled Pavese's poem "A Mania for Solitude":

I can see the sky, but I know the lights already shine between the rusty roofs, and sounds are heard beneath them. A deep breath and my body savors the life of trees and rivers, and feels cut off from everything.

Primo Levi was utterly rooted in Turin. The son of an educated middle-class Jewish family that could trace its arrival in the Piedmont region back to 1500, after the expulsion of the Jews from Spain, he died in the house where he had been bom sixty-seven years before. "I live in my house as I live inside my skin," Levi observed toward the end of his life. It's a comfortable building, with iron balconies and ocher Tuscan

walls, on a street that Philip Roth, who interviewed Levi for The New York Times Book Review the year before his death, likens to New York's residential West End Avenue.

Nowhere in Europe were the Jews more assimilated than in Italy. It was a small population—perhaps 50,000 before the war—but one that had been influential in the nation's life ever since the Risorgimento. Levi grew up in the comfortable neighborhood of Crocetta, near the center of town. Both his grandfather and his father were civil engineers; his mother's family were prosperous merchants. Levi's father was a great bibliophile who instructed his tailor to make the pockets of his suits large enough to hold books. ''On the road, going to bed, getting up: he always had a book in his hand," Levi recalled. His family observed Rosh Hashanah, Passover, and Purim and knew a smattering of Yiddish, but, as Levi remarked wryly, ''a Jew is somebody who at Christmas does not have a tree, who shouldn't eat salami but does, who has learned a little bit of Hebrew at thirteen and then has forgotten it."

Anti-Semitism scarcely existed. As a student at the prestigious Ginnasio-Liceo d'Azeglio, Levi was utterly at home, secure in the cloistered world of the library and the lab. He didn't smoke or drink or ''go with girls." He studied: chemistry, Latin and Greek, Italian history, Dante. His highschool friend Livio Norzi remembers his voracious reading: ''Point Counter Point, The Plumed Serpent, and so on. He taught us all to read." Levi was an ambitious boy. ''I hoped to go far, ' ' he confided in the autobiographical notes he was preparing for his Italian publisher, ''to find the key to the universe, to understand the why of things."

It wasn't until the autumn of 1938, when Mussolini outlawed mixed marriages, banned Jews from universities, and prohibited them from owning certain property or holding jobs in government, that history intruded. "My Christian classmates were civil people," Levi wrote of his days as a chemistry student at the University of Turin. "None of them, nor any of the teachers, had directed at me a hostile word or gesture, but I could feel them withdraw and, following an ancient pattern, I withdrew as well." No professor would sponsor his studies, until he approached a young assistant who responded in the words of the Gospel: "Follow me." In the summer of 1941, a degree in chemistry (summa cum laude) was awarded to "Primo Levi, of the Jewish race."

Even with honors, Levi couldn't get a job. While his father lay dying of a tumor in the flat on Corso Re Umberto, he made a futile search for work and was finally hired by a nickel mine up in the mountains near Turin. In the summer of 1942, he transferred to a lab on the outskirts of Milan. Within a year, the Nazis had arrived, and he headed for the mountains to join the partisans.

Studious, shy around girls, insomniac, Levi was an unlikely revolutionary. Armed with a pearl-handled revolver that he didn't know how to use, he hoped to join forces with the Resistance; instead he found himself allied with "a deluge of outcasts." At dawn on December 13, 1943, Levi and his bedraggled crew woke to find themselves surrounded by the Fascist militia. Under interrogation, he weighed the dangers of identifying himself as a partisan and decided to confess that he was a Jew. He was interned at the notorious detention camp of Fossoli. A month later, the German SS arrived and mass deportations began. "Our destination? Nobody knew. We should be prepared for a fortnight of travel. For every person missing at the roll-call, ten would be shot."

Of the 650 men and women who departed in Levi's convoy for Auschwitz, only three returned. How did he survive? Levi insisted that it was largely a matter of luck. His training as a chemist enabled him to qualify for a job in the I. G. Farben laboratory; an Italian bricklayer who had been rounded up by the Nazis in France shared his meager ration with Levi for six months; and Levi happened to come down with scarlet fever just as the Red Army was advancing on the camp. In the forced evacuation that ensued, some 20,000 prisoners died.

To claim for himself special powers of intelligence or will would never have occurred to Levi; it wasn't in his nature. Yet reading Survival in Auschwitz, the story of his tenure in hell, I couldn't help feeling that his character must have contributed in some way to the miraculous defiance of statistics. One of the most notable things about this book is its magisterial equanimity. There is no self-pity, none of the lamentation characteristic of Elie Wiesel. "There is no why here," said one of Levi's guards; for Levi, inquiring into the "why of things" was simply what one did. His discourse on the social structure of the camp—the way clothes and rations were distributed, the work details, the insanely complicated rules and regulations—is amazingly precise. Auschwitz was an experiment, the most perverse and barbarous ever devised by man, but it could still yield knowledge, and it was in this scientific spirit that Levi observed "what is essential and what adventitious to the conduct of the human animal in the struggle for life."

For all the suffering it chronicles, Survival in Auschwitz is not a gloomy book. Time and again, Levi manages to find pleasure in the slightest things. On those rare nights when he doesn't have to share his bunk, he considers himself lucky. When the weather is warm, he rejoices because it isn't cold. When the ration of watery gruel is more plentiful than usual, he counts it "a happy day." Hope is the momentary absence of pain. In one memorable scene, struggling to carry a heavy soup pot, he begins to recite a passage from Dante's Commedia to a French comrade:

Think of your breed; for brutish ignorance Your mettle was not made; you were made men, To follow after knowledge and excellence.

If Survival in Auschwitz is optimistic, its sequel, The Reawakening, a picaresque chronicle of the months Levi spent wandering the far reaches of Eastern Europe and Russia, is positively buoyant. Liberated from Auschwitz, he found himself shuttled off hundreds of miles in the wrong direction, transferred from camp to camp, an eternal refugee. Yet even as the dream of returning home receded, Levi reveled in his new freedom. The time adrift was "a parenthesis of unlimited availability," he declared, "a providential but unrepeatable gift of fate." Arriving in the ruined city of Katowice, he and his tattered compatriot are "as cheerful as schoolboys." Invigorated by a cup of tea as he's camping out on the floor of a train station in some distant province, he's "tense and alert, hilarious, lucid and sensitive." He had survived. He was alive.

In his interview with Levi, Philip Roth remarked on the "exuberance" manifest in The Reawakening, its atmosphere of celebration. "Family, home, factory are good things in themselves," Levi replied, "but they deprived me of something that I still miss: adventure." The experience of Auschwitz, catastrophic as it was, enlarged his character. "I remember having lived my Auschwitz year in a condition of exceptional spiritedness," he told Roth, comparing his absorption in camp routine to "the curiosity of the naturalist who finds himself transplanted into an environment that is monstrous, but new, monstrously new." For Levi, Auschwitz was "an education."

In October 1945, bearded and in rags, he arrived back in Turin. His mother had survived by hiding in the countryside; his sister, armed with false identity papers, had moved from house to house. No one expected him; Lorenzo, the Italian bricklayer who had done so much to preserve Levi's life in the camp, had reported him almost certainly dead. "I found a large clean bed, which in the evening (a moment of terror) yielded softly under my weight. But only after many months did I lose the habit of walking with my glance fixed to the ground, as if searching for something to eat or to pocket hastily or to sell for bread; and a dream full of horror has still not ceased to visit me, at sometimes frequent, sometimes longer, intervals."

Installed in the flat on Corso Re Umberto, Levi found work in a varnish factory, Duco Montecatini, near Turin, and embarked on the book that would become his masterpiece, typing at night in a freezing storeroom at the factory and scribbling on the tram. "I had a torrent of urgent things to tell the civilized world," he recalled in The Reawakening. ''I felt the tattooed number on my arm burning like a sore." So intense was Levi's need to testify that he would approach strangers on buses or on the street and blurt out that he was a survivor. "Whether we like it or not," he wrote a fellow Auschwitz prisoner after the war, "we are the witnesses and we bear the weight of it."

Levi submitted his memoir to several publishers, including the illustrious house of Einaudi in Turin. It was turned down everywhere. Finally a small publisher, Franco Antonicelli, agreed to bring it out, and J Survival in Auschwitz was published in 1947 under the title Se Questo E un Uomo {If This Is a Man), in a limited edition of 2,500 copies. It got favorable reviews but was largely ignored by the public. Newly married and out of a job—Duco Montecatini had let him go—Levi was hired as a lab chemist at SIVA, a family-owned varnish factory on the outskirts of Turin. His work of testimony, he decided, was done: "It was a forgotten book.

I had dedicated myself to my work as a chemist, I had married, I had been catalogued among the authors 'unius libri'

[of one book], and I hardly thought about this solitary little book any more, even if sometimes I burned to believe that the descent into hell had given me, as to Coleridge's Ancient Mariner, a 'strange power of speech.' "

"Sometimes," wrote Levi, "I burned to believe that the descent into hell had given me, as to Coleridge's Ancient Mariner, a 'strange power of speech.' "

Nine years later, inspired by the enthusiastic response to a talk he gave in Turin at an exhibition of photographs and documents about the deportation, Levi offered the book again to Einaudi, which reissued it in 1958. It hasn't been out of print since.

The tremendous success of Survival in Auschwitz gave Levi the confidence he needed to embark on The Reawakening. It was published in 1963, sixteen years after his literary debut. In his mid-forties, with two books to his credit, Levi "accepted the condition of being a writer," as he put it, but he was still primarily a chemist. By then he was manager of the plant, a job that entailed considerable responsibility. His company, which produced enamel coatings for copper wire, had prospered since the war, and Levi was often on the road, traveling to Germany and Russia. "At the peak of my career,

I numbered among the 30 or 40 specialists in the world in this branch," he boasted to Roth.

For Levi, chemistry was inspirational, both an anchor in the world and a way of interpreting it. When he wrote about his profession in La Stampa, the Turin newspaper to which he contributed an occasional column over the years, it was in a spirit of adventure, and with a lucidity that verged on joy. The behavior of beetles, the challenge of astronomy, the physiology of pain: for Levi, the "two cultures" were one. Science enlivened his writing, made it precise; his job as a chemist got him out of the house. "My factory militanza— my compulsory and honorable service there—kept me in touch with the world of real things."

In 1977, Levi retired in order to devote himself to writing. By now he was a public figure of sorts in Italy, and a celebrity in Turin. When a German television crew showed up to make a documentary and followed him around the streets, people greeted him on the tram. He gave talks in the local schools, answered his ever increasing mail, made himself available to scholars and journalists in his study on the Corso Re Umberto. "He was a person of remarkable serenity, openness and good humor, with a striking absence of bitterness," wrote Alexander Stille, a young journalist who knew about Levi. To Roth, he was a vivid presence, voluble, shrewd, preternaturally attentive: "He seemed to me inwardly animated more in the manner of some little quicksilver woodland creature empowered by the forest's most

astute intelligence. . . . His alertness is nearly palpable, keenness trembling within him like his pilot light."

His intellectual energy was prodigious. He studied Yiddish in order to write If Not Now, When?, his novel about a band of Jewish partisans fighting for survival at the end of World War II. He translated Heine, Kipling, Levi-Strauss, and devoted long hours to playing chess with the Macintosh computer he'd installed in his study. Working with his British translator, Stuart Woolf, Levi was indefatigable. He would sit down after dinner, "beginning around nine o'clock, and go on until midnight or one in the morning, and he'd be up again the next day regularly," Woolf recalled in a television program dedicated to Levi. "Auschwitz had conditioned him to living with very little sleep."

Levi seemed happy in his fame; in a memoir called "Beyond Survival," published in 1982, he noted that If Not Now, When? had won "two of the three most coveted Italian literary awards" (the Campiello and the Viareggio) and was "meeting with great success in Italy among the public and the critics. " On the wall of his study he put up a chart to help him keep track of the translations of his books in many languages. Levi was always dropping in at the Luxemburg, a bookstore near the Piazza Castello that stocked English and American periodicals, to read his reviews. "He was proud of his reputation," recalled Agnese Incisa, formerly of Einaudi. "He didn't have an agent. Everything we did, we had to call up Primo first."

Visitors to the Corso Re Umberto were struck by how close the family seemed. Both of Levi's children were unmarried: his son, Renzo, a physicist, lived next door; his daughter, Lisa, a biology teacher, had an apartment in the neighborhood. Levi's ninety-two-year-old mother, nearly blind and the victim of a paralytic stroke, was confined to her room in the fourth-floor flat. There were two nurses in attendance, and an Arab student, Amir, who helped around the house; but the Levis lived simply, and disapproved of servants. "It was a typical Turinese household," remembered Anna Vitale, of the Comunita Ebraica. "They were well-off, but they didn't live like wealthy people." Levi's book-lined study, furnished with an old flowered sofa and a comfortable easy chair, was his refuge. On the shelves were playful constructions made out of the enameled copper wire manufactured by Levi's factory: a wire butterfly, a wire owl, a bird, and one that Levi described to Roth as "a man playing with his nose." (" 'A Jew,' I suggested. 'Yes, yes,' he said, laughing, 'a Jew, of course.' ") The only emblem of his trauma was a sketch on the wall of a barbed-wire fence: Auschwitz.

As his mother's condition deteriorated, Levi traveled less and less, but in the spring of 1985 he was given the Kenneth B. Smilen award, sponsored by the Jewish Museum in New York, and his American publishers persuaded him to give a series of informal talks in the United States. The Periodic Table had appeared the year before, graced with a blurb from Saul Bellow, and been instantly recognized for the classic that it is. (Twenty publishers turned it down before Schocken Books picked up the rights.) Levi was a great hit in Boston and New York—though he was puzzled that his audiences were entirely Jewish. "I began to wonder if any goyim lived in America. I didn't come across a single one of them!" The press was charmed. "One trusts him instantly," reported Meredith Tax in the Village Voice. To Richard Higgins, writing in the Boston Globe, Levi was a paradox. "He is slight of build, softly-spoken, professorial and dapper in demeanor; but the inner man, say those who know him best, seems to be made of steel." AUSCHWITZ SURVIVOR PRIMO LEVI STRESSES HOPE, NOT THE DARKNESS, read the Globe's headline.

It was a triumphant journey. "He loved his trip to America," recalled Agnese Incisa. "It gave him a chance to be away." Back in Turin, Levi resumed his tranquil routine. He made weekly visits to his publisher, Einaudi, whose offices were just around the comer. He was collecting material for a book in the form of love letters from a chemist to a young girl—"a sort of epistolary romance," according to Arthur Samuelson, who became Levi's editor when Summit Books acquired the rights to his work. Agnese Incisa remembers going to see him at Christmas 1986 and spending hours with him at his Macintosh computer. "It was the last time I saw him happy."

Suicide among Holocaust survivors is hardly uncommon. Levi addressed the issue himself in The Drowned and the Saved, out this month from Summit in a masterly translation by Raymond Rosenthal. He was haunted by the memory of his friend Jean Amery, a philosopher who had survived Auschwitz and committed suicide in 1978. Few suicides occurred in the camps, Levi noted: "The day was dense: one had to think about satisfying hunger, in some way elude fatigue and cold, avoid the blows; precisely because of the constant imminence of death there was no time to concentrate on the idea of death." Suicide, Levi argued, was a reflection of the victim's inward guilt, a punishment for suppressed, unspoken sins; but why punish yourself when you were being punished on a scale beyond what anyone had ever been called upon to endure? At Auschwitz, guilt was superfluous: "One was already expiating it by one's daily suffering."

The subject was clearly on Levi's mind. In one of his La Stampa essays, he examined the death of another survivor who eventually committed suicide, the Romanian-born poet Paul Celan. Celan was a "tragic and noble" figure, Levi conceded, but his inchoate, nearly indecipherable last poems constituted "the rattle of a dying man." They were devoid of hope. "I believe that Celan the poet should be meditated upon and pitied rather than imitated," Levi declared. Three years later, Levi was dead by his own hand.

Perhaps the most devastating aspect of Levi's suicide was its unexpectedness. Even among his closest friends, few were aware of his despair. "He was a happy man, allegro," says the eminent political scientist Norberto Bobbio, who had known Levi for decades. "Three days before his death, he was tranquil and serene." Roth, who visited him in Turin seven months before his death, insisted that "he was as filled with a sense of joy and well-being as a man can be."

But there were those who sensed a darkening in Levi's mood, and not only toward the end. "He was a deeply depressed person," Dr. Roberto Pattono, one of Levi's physicians, told me. "I thought he was suicidal the first time I met him. Years ago, I said to myself: It is only a matter of time." A close friend of the family showed me a poem Levi wrote in the mid-seventies. "It has gotten late, my dears" was the opening line.

"There were brief periods of depression," said Bruno Vasari, the former managing director of Italian public television. It was late at night, and we were sitting in the parlor of his apartment off the busy Via Roma. It was an old-world apartment, full of beautiful things: art books piled up on the coffee table, plush furniture, Impressionist prints on the walls. Vasari, a large, dignified, soft-spoken man with a mane of white hair, seemed weary. He had been in Mauthausen, he told me—"one of the most brutal camps." He opened one of Levi's books and showed me a poem entitled "The Survivor," dedicated to "B.V." In it Levi had quoted some lines from Coleridge:

Dopo di allora, ad ora incerta,

Since then, at an uncertain hour, That agony returns: And till my ghastly tale is told, This heart within me bums.

"The most important thing for him was to write," Vasari stressed. "One had to live not only to write but to tell one's story, to testify." He left the room and returned with another book: the Bible. He opened it to Exodus 13:8. "And thou shalt shew thy son in that day, saying, This is done because of that which the Lord did unto me when I came forth out of Egypt." "To testify," Vasari said again with quiet emphasis, "in the religious sense." He referred me to the opening passage of The Drowned and the Saved, where Levi quotes the boast of an SS man who declares that even if a handful of Jews survive, the world will never believe their story. "Strangely enough," writes Levi, "this same thought ('even if we were to tell it, we would not be believed') arose in the form of nocturnal dreams produced by the prisoners' despair." That was Levi's great fear, said Vasari: that he wouldn't be believed.

Levi had devoted his life to bringing before the world the meticulous evidence of what had happened, what had been done by men to men. He had chaperoned children on trips to Auschwitz, lectured, and given interviews; he had written books. Yet he wondered if he had done enough. "How much of the concentration camp world is dead and will not return, like slavery and the duelling code?" he asked in The Drowned and the Saved. "How much. . .is coming back? What can each of us do, so that in this world pregnant with threats, at least this threat will be nullified?" To those who persisted in asking why the Jews hadn't fled, he replied: What are we doing about nuclear war? ''Why aren't we gone, why aren't we leaving our country, why aren't we fleeing 'before'?"

The Drowned and the Saved, Levi's last testament, is very different from anything he wrote before. What comes through so powerfully in this anguished book is anger—a new emotion for Levi. "I'm not capable of acting like Jean Amery," he once told an interviewer, referring to an episode in which Amery had assaulted a Polish prisoner.

Violence was alien to Levi. There's a moving passage in The Periodic Table where, confined in a cell at Aosta after his arrest by the Fascists, he shares his crust of bread with a mouse: ''I felt more like a mouse than he; I was thinking of the road in the woods, the snow outside, the indifferent mountains, the hundred splendid things which if I could go free I would be able to do, and a lump rose in my throat." That generosity was Levi's essence.

How long could he maintain his equanimity? The Drowned and the Saved is a cry of barely stifled.rage against the Germans. Why did they do what they did? It was their nature. In the Third Reich, "the best choice, the choice imposed from above, was the one that entailed the greatest amount of affliction, the greatest amount of waste, of physical and moral suffering. The 'enemy' must not only die, but must die in torment."

It was this crime against the innocent that obsessed Levi. It was a crime beyond expiation, a wound that festered and would never heal. In his remarkable last chapter, Levi quoted at length from letters Germans had written him, remorselessly showing their evasions and lies, their feeble efforts to justify themselves in the face of what could never be justified. He would not grant the forgiveness they sought. The legacy of the camps was ineradicable. His dead friend Amery had written: "Anyone who has been tortured remains tortured. ... Anyone who has suffered torture never again will be able to be at ease in the world."

For Levi, survival was a gift—perhaps undeserved. He was troubled by the thought that "this testifying of mine could by itself gain for me the privilege of surviving and living for many years without serious problems." Levi considered himself among the lucky few: not only had he lived, he had become a success. "We are those who by their prevarications or abilities or good luck did not touch bottom." The real victims were those who had suffered in silence.

But, in his own way, Levi himself was mute, enduring his life without complaint. Liberated from Auschwitz, he found himself four decades later a virtual prisoner in his own home. From her room down at the end of the hall, his mother, Ester, dominated his existence. She woke up at 6:30, demanded breakfast at 7, called out to Levi day and night. He pushed her around the neighborhood in her wheelchair, kept a vigil beside her bed. When he visited friends, he would rush off after an hour, explaining that he was needed at home. "He was the most dutiful Jewish son who ever lived," says Roth. "He and Lucia were like slaves to the family situation," according to Norberto Bobbio. Levi's mother-in-law, ninety-five, who lived down the block, required equally strenuous ministrations. "Primo had these two old ladies on his back," said one of his friends bluntly. "He was surrounded by sick old women." Why didn't he put his mother in a home? "Out of the question," declared Bobbio. "He was too good a son. He'd seen too much suffering to inflict any of his own."

Few suicides occurred in the camps, Levi noted. "Precisely because of the constant imminence of death there was no time to concentrate on the idea of death."

Levi was on antidepressants, and briefly saw a psychiatrist, but when she tried to probe his feelings of aggression, he abruptly broke off treatment. In February 1987, he entered the hospital for a prostate operation, and was taken off his antidepressant medicine. "Don't visit me," he told Giovanni Tesio, a scholar who had been interviewing him for months. "I'm very boring when I feel badly." The operation was a success, but it brought on a host of distressing urological problems.

Levi seldom ventured out. "He wasn't seeing anyone," said Agnese Incisa. "He would come in and sit in the office and stare." He refused invitations to speak and failed to attend meetings of his social club, the Famija Piemonteisa, or the weekly dinners with friends at the Cambio, Turin's most exclusive restaurant. "He was getting worse and worse," Ernesto Ferrero, an editor at Einaudi, told Valeria Gandus and Gian Paolo Rossetti, who interviewed many of Levi's friends and associates for the Italian magazine Panorama in the weeks after his death. "We cosseted him, telephoned him, urged him to take his mind off things, busy himself with concrete matters.... It was a bad period, but we were sure that it would pass." Toward the end of February, Levi broke off his conversations with Giovanni Tesio. "I don't feel like doing this anymore," he said tersely. "Let's stop."

One of Levi's most persistent complaints was that he couldn't write. Non posso scrivere. He had been a prolific author all his life; his last two novels, If Not Now, When? and The Monkey's Wrench, the garrulous monologue of an itinerant construction worker, had made his reputation as a novelist. But he was terrified that he had nothing more to say. Largely spared the negative reviews that few writers can avoid, he was perplexed by Fernanda Eberstadt's essay on him in the October 1985 issue of Commentary, which claimed that he was insufficiently Jewish, and argued that his later work suffered from "a certain inhibiting fastidiousness and insubstantiality." Levi was a writer who read his reviews.

In April, Levi seemed to improve. "He was eager to get back to work," recalled Dr. Pattono. Stuart Woolf thought Levi "seemed to be in much better spirits than I'd seen him in on the previous occasion." On April 8, Levi wrote a letter to the Venetian writer Ferdinando (Continued from page 84) Camon. "Primo explained to me how much he would have liked to see his latest book translated and published in France," Camon told Gandus and Rossetti, the reporters from Panorama. "The thought that Gallimard, one of the most authoritative publishers on the other side of the Alps, should be interested in his work filled him with enthusiasm." The next day, Levi was offered the honorary post of president of Einaudi, then in the midst of a reorganization. He was flattered by the proposal, remembers Norberto Bobbio, and declined it with regret. On April 10, Giovanni Tesio called, and Levi answered in a happy voice. "Ciao, Giovanni," he said. "We should begin again."

Continued on page 94

(Continued from page 84)

That night, a friend concerned about Levi's state of mind called to see how he was doing. "Bad," Levi reported.

"At least you can play chess with your computer," said the friend.

"Yes, but it beats me."

The next morning, Levi's wife went out shopping and left him alone with his mother and a nurse. A few minutes later, after he'd gotten the mail, Levi rushed out to the landing and hurled himself over the railing of the wide staircase. Death was instantaneous.

That night, all of Italy watched the ghastly television footage of Levi, his face covered with blood, being carried off on a stretcher to the morgue in the Via

Chiabrera. The next morning's papers carried the story beneath front-page headlines. In the weeks that followed, their pages were filled with tributes, reminiscences, appreciations of his work. Rita Levi Montalcini, a childhood friend of Levi's and a Nobel laureate in medicine, speculated in a lengthy interview that Levi hadn't committed suicide at all. Perhaps he had plunged over the railing by accident, while calling down to the concierge. More likely, Dr. Montalcini surmised, it had been what psychiatrists refer to as a raptus, a sudden fit of insanity that could have been precipitated by some irregularity in his reaction to the dosage of his antidepressant drugs. Whatever the cause, it was a frightening way to die, especially for a chemist, who could have found less violent ways to kill himself.

Every suicide, Levi had written, apropos the death of Amery, provokes "a nebula of explanations." Had there been financial problems? The year before, the house of Einaudi had gone into receivership, and Levi stayed on while most of the writers on its list jumped ship. Some people intimated that Levi's loyalty had cost him a lot of money, but Agnese Incisa told me that Einaudi had managed to pay "most of the royalties" from If Not Now, When?, despite its own financial difficulties.

Or was it heredity? In The Periodic Table, Levi had offered portraits of his eccentric relatives: the doctor uncle who neglected his practice and squandered his days on a cot in a filthy attic on the Borgo Vanchiglia reading old newspapers; his

grandmother, who spent the last twenty years of her very long life mysteriously cloistered in her room; a remote ancestor, the uncle of his maternal grandmother, who took to his bed when his parents refused to let him marry a lowly peasant girl, and stayed there for twentytwo years; his grandfather, rumored to have killed himself over his wife's infidelities, the wife herself half mad. Levi's tone was ironic, but the history is significant.

Inevitably, there was speculation that the Holocaust had reached out to claim another victim. Levi "had built a public image for himself, but inside he was very corroded," testified Ferdinando Camon in Panorama. "The operation of memorizing, cataloguing, bearing witness to the Nazi horrors and barbarities took a tremendous psychic toll. This is a suicide that must be dated back to 1945. It did not take place then, because Primo wanted (and had) to write. Having finished his work (The Drowned and the Saved ends this cycle) he was free to kill himself. And he did."

Perhaps it did go that far back. As he was wheeled into the operating room last February, Levi rolled up his sleeve and pointed to the number tattooed on his arm: "That is my disease." Reading over Survival in Auschwitz, I was struck by the passage where Levi suggested that to come down with diphtheria in a concentration camp would be "more surely fatal than jumping off a fourth floor." That book was written in 1947, in Levi's fourth-floor flat on Corso Re Umberto. □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now