Sign In to Your Account

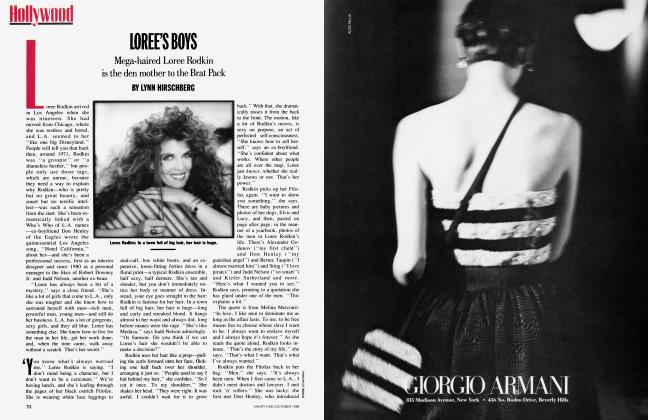

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

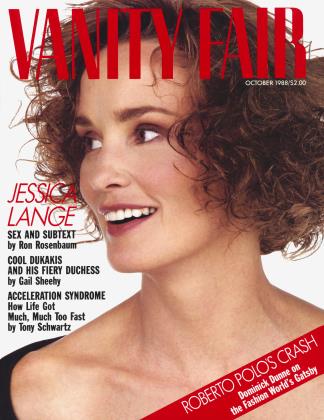

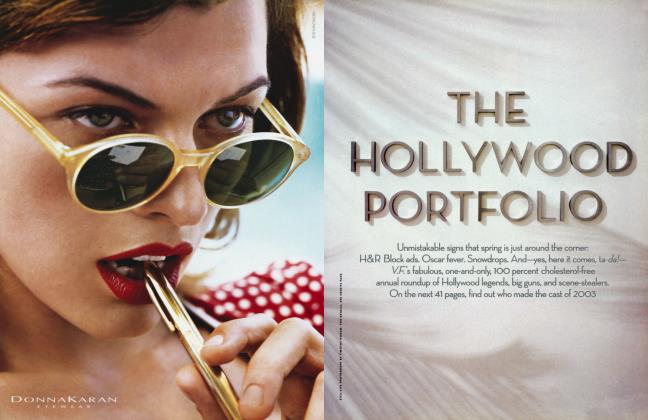

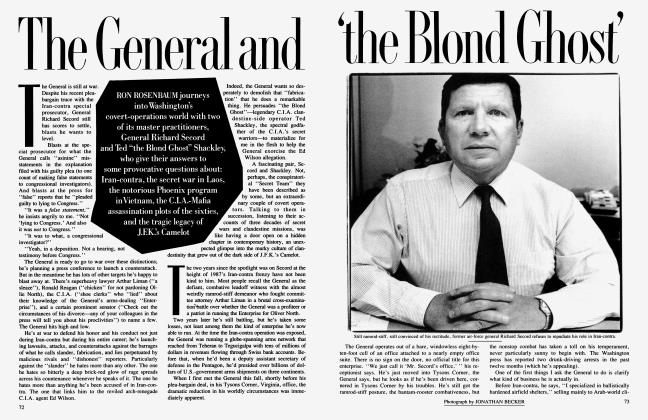

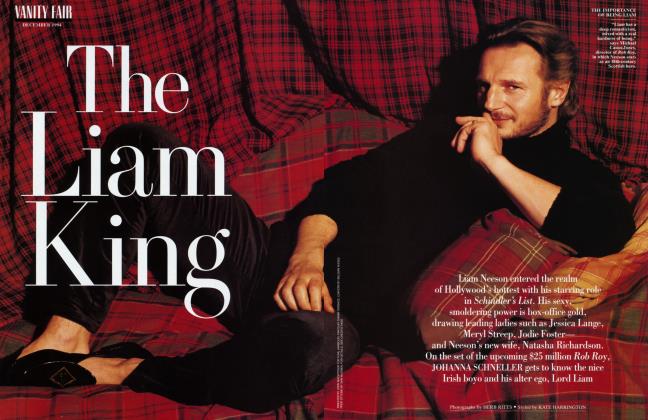

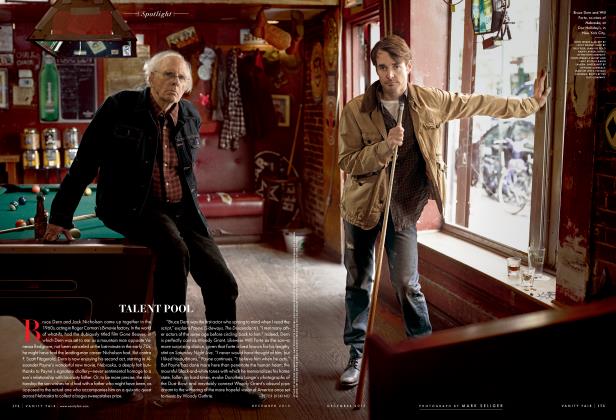

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowAfter her own personal baby boom, Jessica Lange is back, with two new movies about to break. RON ROSENBAUM, putting aside his niggling "Sam Shepard problem," asks her about her Bowery boho past, those legendary steamy outtakes with Jack Nicholson, and how she approaches The Work

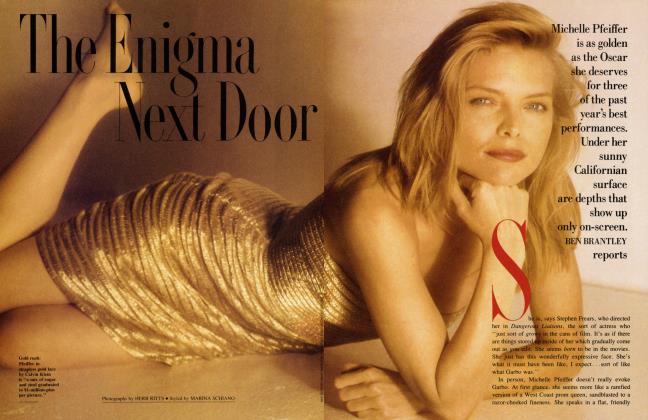

October 1988 Ron Rosenbaum Herb Ritts Marina SchianoAfter her own personal baby boom, Jessica Lange is back, with two new movies about to break. RON ROSENBAUM, putting aside his niggling "Sam Shepard problem," asks her about her Bowery boho past, those legendary steamy outtakes with Jack Nicholson, and how she approaches The Work

October 1988 Ron Rosenbaum Herb Ritts Marina SchianoWe're talking about subtexts. Jessica Lange is explaining how she looks for the clue to playing a character in an emotional substratum that goes against the grain of the surface feeling in the lines. She's extremely serious about the emotional technology of acting— it's a key to her character. "Ultra-serious about The Work" is the way Jack Nicholson describes her, with capitalized enunciation, although he's quick to add that, despite her Method studiousness, "as a human being Jessie can get down and have some fun."

Nicholson claims he even saw the subtexts, the subtle dynamics Jessica brought to her role as Dwan, the dreamy starlet in King Kong. Which led him to cast her in The Postman Always Rings Twice, a role that made people realize the King Kong starlet possessed extraordinary acting ability, not to mention incendiary sex appeal. As an ultra-serious person myself, I promise not to mention her incendiary etc., despite the fact that—"as a human being"—it is difficult not to notice that Miss Lange, sitting on a couch across a coffee table from me, is wearing black culottes which have a sly subtextual way of sliding up and down her legs as she shifts about discussing The Work.

But to return to The Work. Jessica is describing the difficulty she had searching for the subtextual clue to playing Frances Farmer, the radiant starlet whose life turned into a nightmare of psychiatric-abuse horror. Even after reading everything that had been written by and about Farmer, after having screened all her films and interviews over and over again, she hadn't found her way into the role. Until "somebody came to me out of the blue with a little home movie of her where she was doing summer stock before she joined the Group Theatre. And there was a little black-and-white faded image of her walking toward the camera and then turning. And it was really in the body language in just that short moment that I saw something that I really could... it was a shyness that you didn't see in anything else of her—her movies or interviews or performances. And that you wouldn't ultimately assume was there, because this was such a violent, powerful woman. But there was a real physical, almost painful shyness about her." The ghost of Frances Farmer flits across her face for a moment. "Yeah," she says, returning to the room. "I always like to find the contrasting. . . A shy person being violent is a lot more interesting to me than a powerful person being violent."

Finding the contrasting emotional subtext was also the key, she says, to playing Julie, the radiantly scrumptious soap-opera starlet in Tootsie (for which she won an Oscar in '83). She saw a darkness beneath the radiance.

"The clue to that character," she says, "was that sense that something was hurt. At the soul of that character I felt there should be something very sad."

She found the locus of that sadness in some lines of dialogue the content of which is perhaps the most overlooked of any in the film because of the, well, incendiary context in which they are delivered.

Jessica's Julie is lying in bed next to a bewigged, curlered, nightgowned Dustin Hoffman as "Dorothy." They're sharing a bed in Julie's childhood home and she's rambling on about childhood memories in an adorable sleepy singsong that has Dustin Hoffman utterly enraptured and totally frustrated. The comic focus of the scene, of the camera, is on Hoffman's eyes: beneath his false lashes they reflect the emotional meltdown he's experiencing just from the pure sound of her voice; he's not even listening to the words, something about shopping for wallpaper with her mother. But for Jessica it is precisely in those words that the key to her character can be found. "Her relationship to her mother wasn't explored in the script, but I always pinpoint that scene when she talks about how her mother took her to buy wallpaper. I figured her age then to be right about the beginning of adolescence. Maybe twelve years old. And then her mother dies soon after. And there has to be a hurtfulness that comes from that that a daughter never gets over... So on the surface Julie seems like..." She shifts into Julie's airy, spacey tones: " 'Everything's O.K. I don't have a man. I don't have this, I don't have that, but it doesn't matter. I'm going to settle for this in my life. I'm going to settle for this man. And, you know, I really don't have any great aspirations to being an actress. I mean—working soap operas is O.K. It's all O.K. It's all O.K.' "

A couple of things happen as Jessica does the voice of Julie. She makes you hear that wistful lunar underside to the all-O.K. sunniness; it gives Julie a dignity and complexity, a sense that despite a surface spaciness she's—like Jessica— far from being an airhead.

The other thing that happens is that when she takes on the voice of Julie her face, for a few fleeting moments, undergoes a subtle reconfiguration. Moments before, she looked attractive but, well, unspectacular. When she does Julie's voice, her face lights up with a flash of Julie's Marilyn-like lusciousness. Similarly—and a bit more disconcertingly— when she's speaking of the shy and violent subtexts in her Frances Farmer role, her face takes on the haunted, reckless look of Frances's post-asylum persona.

It's something you notice when you rerun her films: it's her unique technical gift as an actress, the ability to register both text and subtext simultaneously and intelligibly.

Lange thinks her facility at this may be attributable to the years she spent in Paris as a disciple of classical-mime guru Etienne Decroux. But before we get deeper into that (rest easy: she was never one of those white-faced pests who accost defenseless passersby in mime-infested urban areas), it might be wise to disclose several subtexts beneath the surface of our conversation.

Subtext One: Secrecy. Jessica has asked me not to reveal the name or even the approximate location of the Virginia country inn that is the site of our conversation.

"How about the region of Virginia?" I ask.

"How about just Virginia?" she counters.

"What if I were to say it's not far from Patsy Cline's hometown?" I suggest.

She thinks a moment. "That's all right. Fairly vague."

Fairly vague and actually, due to my impoverished knowledge of Virginia regional geography, fairly misleading.

But that's why she likes it. She seems concerned not only with her family's privacy but with their safety.

"Lots of lunatics out there," she says uneasily.

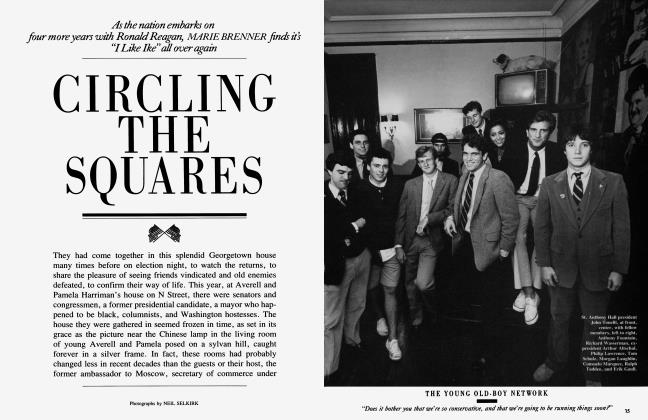

She and Sam Shepard and their three children (one fathered by Baryshnikov) have led a relatively reclusive life together, avoiding Hollywood like the plague. But she's willing to emerge briefly from the zone of silence they've wrapped around their lives because she's got two movies coming out. One of them, Everybody's All-American, is a big Hollywood production in which she co-stars opposite Dennis Quaid. She's confident about that one— she feels her performance in it is her best work in a long time. The other one, Far North, is a smaller-scale film written and directed by Sam Shepard, and she's a bit nervous about its reception for a number of reasons (Subtext Two).

"I see a lot of purposeful sexuality. But there's no fire. These people aren't electric."

Although she's clearly pleased to be returning to moviemaking full-time after six years in which only three films were squeezed in between pregnancies (she's got three more Hollywood movies lined up as these two go into release), she's also clearly ambivalent about whether she can make Hollywood movies without being swallowed up by the Hollywood she's fled.

In fact, the night after we first spoke, the night before she was to be photographed for this story, she had a nightmare about being swallowed up.

In her dream she was fleeing up the peninsula of Italy to escape a huge whale that was devouring everything in its path in pursuit of her. While there may well be other subtexts in this dream, certainly one of them seems to be a fear of being swallowed up by the leviathan, Kong-like appetites of the publicity-industrial complex of Hollywood, in which the interviewing process (Italy = I-tell?) makes her an accomplice in her own immolation. She had tried, like Frances Farmer, to give Hollywood the boot (Italy = boot?). Now it threatened to devour her anyway.

I ask her if the recent move she and Shepard made from New Mexico to Virginia could be attributed to a desire to get even farther away from Hollywood. She says it wasn't that calculated.

"We were living in New Mexico until two years ago and somehow it just didn't feel right to me. You know you can feel when you're meant to be in some place and then you know your time there is past. And it's time to move on. And I really felt that strongly there. We didn't have anywhere to go—I mean, we kind of picked this place out of the air."

"From a map?"

"Well, not exactly. I mean, we were in New York. Sam was doing his play. I was pregnant and very. . . I don't know, moody and restless and feeling crazy and one day I looked in The New York Times and I saw this picture of a farm down in [region deleted] Virginia, and I thought, Well, we're going to look at this place. And that was it. "

She'd been drawn to this region before, she says.

"Sam doesn't fly, so we drive everywhere," she says. (The guy who played Right Stuff ace Chuck Yeager is afraid to fly?!) "I haven't driven places since the sixties [when she dropped out of college to take a Kerouac-inspired pickup-truck trip across America with her boyfriend]. But it's great because we go through routes that I remember from the sixties. And this one time we were driving down to New Mexico and we stopped in Winchester, Virginia, for a night and I started walking and I ended up in the cemetery. And I felt this incredible kind of pull. I don't know why, but I do have a fascination with cemeteries. Every place I go I try to find the cemetery. They're the most mysterious, beautiful places. I found one in Louisiana when we were doing Everybody's All-American that was just amazing. But anyhow, I ended up in this cemetery in Winchester, Virginia, not knowing why. This was before I'd been sent a script on Patsy Cline. And then a couple of months later they sent me Sweet Dreams and I realized she was buried there. . . Eerie."

Subtext Three: A Different Kind of Eerie Feeling, or, Haunted by the Past. She brings it up three times in the course of our conversations. She felt it first in that cemetery in Louisiana. A yearning that has kept obtruding itself from beneath the surface of her otherwise pleasant present existence.

"I don't know what it is, but. . . I felt it down in Louisiana. It's like you're yearning so much for something and you can't really pinpoint it."

It takes the form of visitations from the past.

"In the last six months, moments of my past will just sweep over me for some reason. I don't know what it is, I'll just get drawn into that for a day or two days or a week and it's very haunting."

"What kind of moments from the past?"

"Well, there's that period of time—that whole sense of being down there in SoHo in the sixties when everything was just beginning to happen."

She feels it in a "real, sensory" way, she says. "The smell of summertime in the streets of New York. That moment in my life where everything started to really come alive, when you began to sense the possibilities of things."

If you listen to Jessica, the high point of her life was not, for instance, that moment in 1982 when with the release of Frances and Tootsie she suddenly became Hollywood's most desirable serious actress, but those moments from the sixties which still haunt her now with pure, uncomplicated, idealistic joy. May 1968 in Paris, for instance.

"There will be some feelings in the morning air that will take me back to that time." She talks about wandering accidentally into the middle of a demonstration on the Champs Élysées.

"All of a sudden, out of nowhere, the students and the workers, everybody, started coming from the side streets. And I thought, This is great! This is the greatest thing in the world!" Then she adds, simply, "It was."

Part of the pure joy was the feeling of escape. She grew up in the far north of Minnesota, listening to Bob Dylan and longing achingly to get out. "Subterranean Homesick Blues" was her anthem. And she followed Dylan's route out of Minnesota. First a brief spell in the student Bohemia of Minneapolis known as "Dinkytown." Then a couple of years on the road in the pickup truck; then to New York, where the whole postmodern downtown scene was just spilling out of illegal SoHo lofts into galleries and the dread "performance spaces."

She and her boyfriend, a Spanish photographer she later married—and painfully divorced—moved into an illegal loft on the Bowery. Even taking out the garbage is romantic in her memory. "Because we were living there illegally, we'd have to run out and hide the garbage somewhere else. It was great."

She wasn't acting then. She became a SoHo artist for a while (painted Formica boxes were her specialty), but the important thing was being a part, however obscure, of this starry-eyed avant-garde, the Paris Commune of postmodernism.

"It was exciting," she says. "Painters were painting things that had never been seen before. There was that whole underground-theater thing. And dance—there were a lot of performances that nobody has ever seen or will ever see, that there's no documentation for, but for the moment they were great." In fact, she soon shifted from painting to dance—which was her eventual route to acting—when she joined the small avant-garde dance company of Ellie Klein.

How would you describe the aesthetic of Klein's company? I ask her.

"Well, she came out of Merce Cunningham's company, but she had this wild, exotic imagination, so it branched into all sorts of other things—there were dancing pieces of toast."

"Were you a dancing piece of toast?"

"No, I never was," she says, laughing. But she did get to tap-dance with the stars of the Dixie Hotel tap revue.

"This woman was fascinated with all kinds of dance; we studied tap and we'd go over to the Dixie Hotel and they were some of the greatest, like Sandman Sims and Chuck Green, and these old black tap dancers would come to the loft and we'd all tap together."

Exhilarating as the downtown scene was, she was still looking for something more: a teacher.

She found her first one in Paris: Etienne Decroux, the revered guru of classical mime whose indirect responsibility (he taught Marcel Marceau) for the ineptly posturing plague of white-faced pests is somewhat mitigated by his contribution to the development of Jessica Lange as an actress. When I ask her if her ability to register with clarity conflicting emotional subtexts could be attributable to her training with Decroux, she hesitates, then says, "It could be, yeah. We would work sometimes for weeks on just the movement of a hand, just from the physical point of view, getting the technical thing right. Or a movement of the eyes. And then all of a sudden one morning he'd sweep in and say, 'You're not gymnasts, you're dramatic artists.' And then he'd take a movement that had been just physical for weeks and spin these incredible tales, these incredible fantasies about it. And it became a literature."

Her reverence for Decroux borders on guru worship.

"He had this ability to captivate. He was comparable to Balanchine or Strasberg; he had that ability to obsess people so that all they wanted to do was to please him. Did he love you? Did he not love you? I've only seen that with Balanchine. I was in the presence of his company when Misha was dancing with him... and people kind of breathed for him, you know."

She never worked with Strasberg, but she did work with one of his acting-teacher disciples, Sandra Seacat.

"She really changed things around for me. She got me at the moment where it was all beginning to come alive, and it was a great catalyst for me."

What was her method like?

"She was out of the Actors Studio, but then she really diverged from Method acting. She did a lot with Siddha yoga. You know, she was a follower of Guru Baba Muktananda."

"I never became a follower of his," Jessica says, "but Sandra brought a lot of that stuff into her early work with me, relaxation and meditation."

At what point was it that you started working with her?

"When Bob [Rafelson] and Jack cast me in Postman. They wanted—Bob suggested it, and of course I resisted, and it took me a long time to kind of give in to working with her. But then once I did it was wonderful. 'Cause I am the kind of person that needs a teacher once in a while."

When she speaks of her experience "doing Postman with Bob and Jack," she's alternately rhapsodic and annoyed. Rhapsodic about the communal artistic idealism of the effort—it was her first serious film project, the first time she had been taken seriously as a film actress. And annoyed that Postman didn't get the respect she thought it deserved. (Most critics praised her performance but found fault with the film.) Just thinking about the injustice of it provokes a tirade.

"People whined about how Postman didn't live up to the original. But that was so much bullshit. It was actually, I think, an amazing film, and I still see people stealing bits and pieces from it."

"Really?"

"Yeah. Especially in the area of . . . in the whole sexual thing. I mean, since then I've seen a lot of films where they've fucked on kitchen tables—you know what I mean?"

She laughs. Then gets serious. "I'm always amazed at what critics like and don't like. There are a couple of films out now that have gotten good reviews, and I've sat through them and thought, Am I out of sync? I see a lot of posturing, I see a lot of purposeful sexuality. . . and I don't get it. There's no fire. These people aren't electric."

She blames the decline of movie acting on TV.

"The majority of people are so programmed by television that they cannot even recognize what is truthful on-screen and what is just soap-opera acting. It's just maddening to me. Because what's happened is that because of television and the popularity of television actors in these dreadful sitcoms it's brought the level of expectation down so low that people don't even know when they're seeing an extraordinary performance. I'm a real TV hater. I just hate it with a passion. You know, you hear that Bruce Willis is being paid $4.5 million for his next film and you think, Really? Four and a half million? That's getting up in the category of Dustin Hoffman and Jack Nicholson."

"You haven't seen the subtext in Willis's work?"

"Yeah. . .right. I mean, what is this based on?"

To return to Jack and Jessica and Postman, Nicholson once told me that Jessica had developed her own history for the character of Cora, but that Rafelson had cut a crucial scene in which she explains how she came to be there at that diner when Nicholson arrived for their fatal encounter. And so what had been text became subtext. I asked her what that now subtextual, submerged story had been.

"Cain didn't really write much history of the people in the novel, but I always feel you've got to know the people you play from the time they were bom until the moment the movie starts to really have an honest connection with them. I always do that, always create a history." The key element in the history she gave Cora was that she saw her as a failed actress.

"I figured that she was a lower-middleclass girl trapped in the Depression who had come to Hollywood as an aspiring starlet—got off the train having won some local small-time beauty contest and wanting to make it big. No doors were open, so maybe she had to fuck around a little to get where she was going. And then at some point she gets scared and opts for what's a little bit easier. Which was marrying some guy she didn't love, but at least she had a roof over her head. That kind of desperation. I saw a lot of it in New York when I was there. I saw a lot of it during the period I was trying to model—girls who based everything on their beauty... But, you know," she says, shifting gears, "if I were to play that part again, I might play it a bit differently."

"How so?"

"I might play her less as a victim of time and place. Actually, maybe more of a murderess. Maybe more like I have the evil seed in there."

"More consciously wicked?"

"Yeah, more manipulative. More of a temptress and a murderess."

Postman was a landmark movie for Jessica, but also for the depiction of sexuality in American films. In fact, Nicholson thinks it failed in this country and succeeded in Europe because "Americans like films that are sexy, not sexual. This was sexual."

Just how sexual it was, and how its sexuality was achieved, has made it a subject of subterranean Hollywood legend. There are tales of "steamy outtakes" of Nicholson and Lange doing—well, there's all sorts of speculation about what they were doing. Nicholson and Lange are a bit elliptical about it themselves, but if you believe them, whatever they were doing was all part of The Work.

To bring the chemistry between them to a boil, Nicholson tells me, they had to establish a permissive set of rules on the set of Postman. "To open up the area of erotic acting, we had to establish some kind of on-set society so that. . .I didn't want to be holding back, and yet I didn't want Jessica to feel like she had to lock herself in at night for fear I'd be crawling naked through her window, a sex maniac or something.''

I ask him to explain a bit more the nature of the "on-set society.''

"Well, I'm not going to walk up and pat Jessica on the ass if I see her tomorrow morning. But on the set if I wanted to. . .I didn't want to be into that kind of censorship while playing the part.''

And so, he says, "the society was created where that was permissible. It's not goosing someone in public. There's no clawing.

"But you could express yourself sexually?''

"Right—I mean at work, on the job. And what 1 loved about Jessica is that— like Ginger Rogers made Fred Astaire more sexual—Jessica made me look good as a partner. It was also exciting watching the birth of a great actress.''

When I mention what Nicholson has said about creating an "on-set society," Jessica says, "You know, he may very well have done that. It was an unreal time . . .Ummm. We were shut off in this little mountain pass outside of Santa Barbara, and it was really a world unto itself. And I was alone then—it was before I had any kids or anything. It was all very mysterious. It was like a dream time. It was great."

Let's fast-forward now from dream time to real time. Past Postman. Past Frances and Tootsie, which earned her two Oscar nominations in the same year (the first time in forty years any actress had pulled that off). Past the sudden retreat from Hollywood—like Fay Wray fleeing Kong, like Frances fleeing the asylum—at the point when she was the most desirable, in-demand actress around. Past the shift in her personal life from the long-distance relationship with Baryshnikov to the live-in liaison with Shepard (which began when he played her boyfriend in Frances and succored her during the emotionally ravaging months of playing that role).

And, finally, through the last five years, in which—despite having made only three movies: the sturdy, worthy Country, the luminous Sweet Dreams, and the all-star disappointment Crimes of the Heart—the reclusiveness has not diminished her stature. Which brings us to the two new films.

On the surface, they're two very different roles. In Far North she plays an uneasy yuppie flying in from a big-city job to her far-north country home to deal with her difficult family. In Everybody's All-American, which might be called Far South, she plays a late-fifties New Orleans homecoming queen through a difficult quarter-century of marriage to a legendary football hero.

While the uncertain Katie of Far North and the all-too-certain Babs in Everybody's All-American are geographically and characterologically antipodean, they're similar in that once again Jessica plays well-intentioned women trapped in—and trying to escape from—destructive conventional marriage and family structures, bad homes. When you consider the destructive families of Frances and Crimes of the Heart, the failed marriages of Sweet Dreams, Country, and Everybody's All-American, you realize that her only "good" film relationship was with King Kong.

I ask her if she thinks there is a pattern there. "So many of my roles really are about having to escape from home. That's a. . .that's funny. . .yeah, I suppose it is. I hadn't thought of it—it's a prevalent thing in my choice of roles."

Which is perhaps why she's particularly nervous about Far North: not only does it deal with the emotional configurations of her own family, it was written and directed by the man she's—well, not married to, but who lives with her and has fathered her children.

She laughs nervously when I first introduce the subject of Far North.

"What are you laughing about?" I ask her.

"Nothing," she says at first. Then: "I mean, it's such an eccentric, strange film. For me it's very personal—that's why I get nervous about it. Because I've never done anything so close, literally and figuratively, to home. I don't know how I feel about it yet."

I ask her how the Far North project came to be.

"Well, it was prompted. . .I was pregnant with the third baby, and there's that restless thing of wanting to do something and not let too many years pass just child bearing. I thought the only thing I could do in a limited amount of time is a play for cable or something. So I asked Sam if he'd want to direct a play so we could work together. He said yeah, but if I'm going to do that, let me write something for you. He started writing and then he said, no, he didn't want to do it as television, and by that time I'd been disenchanted with doing anything for television. The medium doesn't work for me. So he just continued writing it, but now with the idea of shooting it as a film."

It was shot near her hometown of Cloquet, Minnesota, and in the nearby Lake Superior iron-ore port of Duluth.

In the opening scene, her fictive father is driving his horse-drawn buckboard at a furious pace when the horse spooks and throws him. When Katie (Jessica) flies in to visit him at the hospital, he makes an imperious mythic-primitive request: she must avenge him by shooting his horse. The rest of the movie consists of her wrestling with this parental command and with the female members of her family who have stayed behind in the home she fled for the city.

"You know Sam," she says. "He borrows generously from reality. His work starts with something seemingly real and then expands into areas that are only Sam's imagination. Which makes it so great. I mean, he took the opening incident—that actually happened. My father was driving his buckboard down the road and the horse spooked and he was thrown. That was the departure point."

A more important departure point was her emotional relationship with her father.

"One of the most important motivating factors in my entire life has been trying to please my father. Because he is an amazing man, unbelievably powerful in his personality and magnetic and riveting. And polarizing. I loved him and hated him. But I always, always, needed his approval, and it was hard to get. It still is hard to get."

As for the movie "Sam's imagination" concocted from this—well, before describing it, I suppose it's only fair that I disclose one further subtext: my Sam Shepard problem. I think he's a terrific actor, and I know he's got a Pulitzer, but I just don't get the acclaim as a playwright—in the same way Jessica just doesn't get Bruce Willis's $4.5 million. And it's not that I don't get it because I find him obscure or difficult in his flouting of narrative and structural conventions—to me the work seems not obscure, but painfully obvious. Still, those who like Sam Shepard may find Far North a brilliant film.

As for me, I found it pretentiously mythic (flash cuts of befeathered primitive warriors and dream sequences of ritual sacrifices and the like); derivatively Maileresque to the point of self-parody (the father claims he "can smell it" when a woman is pregnant; there are portentous laments about the disappearance of real men from the landscape); pretentiously literary (there are echoes of the dying-fertility theme of The Waste Land and a final moonlit-wood sequence which apes A Midsummer Night's Dream), and filled with a hackneyed apocalyptic ponderousness.

There were times when this subtextual prejudice of mine would intrude into the text of our conversation, at one point prompting Jessica to rise in Shepard's defense.

It happened when I was suggesting some parallels between her life and Frances Farmer's: both of them rebels in their teens, both suddenly Hollywood starlets fighting for artistic respect and then trying to escape from Hollywood— Jessica, obviously, more successfully than Frances. Then, perhaps disingenuously, I asked her if she'd ever considered the parallel between Frances's big love, Clifford Odets, and her Sam Shepard. Both were acclaimed, overpraised (I didn't say that) avant-garde playwrights who brought with them the aura of the artistic seriousness their respective actresses craved. Of course, there was a darker side to the Farmer-Odets relationship: he dropped her cruelly, both personally and professionally, precipitating her descent into psychiatric-lockup hell.

Jessica is quick to pick up on the insinuation and stirringly defends her playwright.

"Well, obviously she [Frances] was an actress, he [Odets] was a brilliant playwright. That's where the parallel ends. I don't think Odets was a very kind man, you know. Sam's an extremely kind man. I'm lucky to be with such a kind man." Her heartfelt declaration made me ashamed of my invidious emotions.

Jessica would like to correct a misconception. We've been talking about Everybody's All-American, in which she plays the Last Southern Belle, a late-fifties homecoming queen in the inhospitable decades that follow her moment of Gone with the Wind glory. I bring up Jessica's own Gone with the Wind obsession; she's spoken previously of her girlhood fascination with it, how growing up in the far north she'd read and watch that fantasy of the far south over and over again. But not the whole thing. It was only the first half that obsessed her. "I found the second half very hard to watch."

It was the romance of the South before the Fall that appealed to her.

"I always found a kind of mysterious connection with that time in history," she says, "especially sitting out there in the woods of northern Minnesota thinking about what life could have been like if I'd been born into the right place and the right time. I can walk through a Confederate cemetery and just weep. The idea of Robert E. Lee still makes my heart pound."

She realizes that the antebellum civilization of the South was based on an institution which was "inexcusable, obviously unacceptable. But there's something about the idealism of the South that appeals to me—an attempt at something beautiful, a romantic ideal of civilization that was destroyed by something more practical."

All of which makes her role in Everybody's All-American particularly interesting. Because the emotional locus of the film is in the Second Half; it's about the ultimate southern belle making the color-draining transit from Scarlett to Blanche.

"I love that line of Blanche's," Jessica says, "when she's talking about nursing the family that's dying off: 'The long parade to the graveyard!' You know? That's really what happened to the South."

When we first see Jessica as Babs, she's a twenty-two-year-old in a moment of glory: a homecoming queen, a young goddess of southern white womanhood engaged to godlike football hero Gavin Grey (Dennis Quaid). What follows is a twenty-five-year plunge into the disheartening realities of ordinary life. Gavin's career in pro football fizzles out in frustration. The god-and-goddess-like romance of their union fizzles out into infidelity and bankruptcy. And finally Babs passes up the chance to run off with longtime nice-guy admirer Donny (Timothy Hutton) despite his willingness to offer her the goddess worship she's been deprived of.

"He didn't understand her either," Jessica says of the Tim Hutton character. "He just worshiped who she'd been."

"There was something about her that eluded both men?"

"Both of them were stuck in time. She was able to adapt to the disillusion. They just wanted the old illusion." Another couple of jerk men who don't know how to be human.

"What do you think is wrong with men?" I ask her.

"It's more to do with the displacement of the family," she says. "I think that it's not only what's wrong with men. It's what's wrong with women, what's wrong with children. I think that's what's wrong with civilization in America—the family's become disposable. You know, if you don't like your wife, you can get rid of her; if you don't like your husband for a day, you can get rid of him."

She says she fears the disintegration of the family unit as a "signal of the end, of this whole kind of apocalyptic feeling that is in the air now." (A strain of thought that is probably Sam's bad influence. Sorry, I can't help myself.)

"But," I say, "in a lot of your roles in your movies, the conventional family unit is an instrument of torture."

"Yeah, but you've got to see the flip side: the horrible despair and rage and loneliness that I felt within the family unit . . .on the flip side was the greatest joy, the most fulfilling.

"But you yourself have resisted conventionalizing your family situation, right?"

"You mean in the sense of marriage?"

"Yeah."

"Yeah. I do. Because I think marriage is about your commitment to the other person. It has absolutely nothing to do with some government decree. The legality of it means absolutely nothing to me whatsoever. That's not going to make people live their lives together and be responsible to each other."

She pauses, almost surprised at her passion on the subject.

Part of it comes, she says, "from living outside the law for so many years, in the sixties and seventies."

"That Dylan line," I suggest. " 'To live outside the law—' "

She completes it: " '—you must be honest.' "

She laughs. "Yes. I mean, I've never been governed by the idea of government. My heart still stops if I see a policeman come up next to me."

This very morning, she says, the outlaw subtext suddenly made its presence felt.

"Even though I know I'm one of the most respectable citizens, I saw a cop today, driving over here, and it was like . . .You get that rush of adrenaline for a second and you're lost in time. You say, 'Omigod, this is it.' And then you realize, 'No, wait, I'm not. . .I'm clean. I haven't done anything. I'm going to an interview. That's good. They're not gonna lock me up.'

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now