Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowTHE WEATHER OVERGROUND

In Sidney Lumet's Running on Empty, sixties radicals are movingly confronted with eighties reality

Movies

RON ROSENBAUM

In the bleak winter of 1970, some of the most visible leaders of the antiwar movement suddenly made themselves invisible—dropped out of sight, altered their appearances, adopted carefully forged new identities, and began building powerful explosive devices. In the parlance of the day, they Went Under. Some of them never came back up.

Over course next seven years they set off bombs in the U.S. Capitol Building, in New York City Police headquarters, and in a dozen more "symbols of American imperialism.'' They called themselves the Weather Underground Organization, and the bombs they set off set in motion what would become the longest manhunt in the history of the F.B.I.

The F.B.I. versus the Weather Underground: one of the world's most highly regarded internal-security apparatuses pitted against a group of grad-school dropouts. But to the surprise of everyone, in pure cops 'n' robbers terms the Weather Underground won. The F.B.I., which was able to crack the Mafia wide open, never broke the Weather Underground's security, never infiltrated or "turned'' any of the original group that Went Under, never stopped them from carrying out their explosive acts of "armed propaganda." In fact, by the late seventies, when the Weather Underground broke up in ideological wrangling and many of the original crew (Bernardine Dohrn, Mark Rudd, Jeff Jones, Bill Ayers, et al.) began to surface and surrender voluntarily, there'd been a rather remarkable ironic reversal: several of the F.B.I. chiefs who'd directed the manhunt for the Weather Underground were indicted, tried, and convicted for violating the law in the zeal of their search for the fugitives. (President Reagan pardoned the F.B.I. men shortly after he took office.)

None of which is to suggest that the tactics of the Weather Underground were admirable. While they regarded themselves as successors to abolitionists of the John Brown stripe, justifying violence because of moral urgency, even their sympathizers on the left regarded them as self-destructive moral purists, driven crazy by the war. (Literally selfdestructive: while they took care to see that none of their "symbolic" bombings resulted in "civilian" casualties, they did manage to kill three of their own number in the notorious town-house bomb-factory explosion of 1970—and they undoubtedly inspired less adept bombings by radicals unaffiliated with them, some of which did result in death.)

Despite its deadly extremity—indeed, because of it—the Weather Underground experience is one of the great untold stories of what is growing to seem a stranger and stranger epoch in American history. Actually, there are two untold stories. One, which will probably never be told, is the story of how—on the level of pure clandestine technique—they managed to outwit the F.B.I. The Weather fugitives who have surfaced have been silent about just about everything, but particularly about what the intelligence trade calls "source and methods."

The other untold story is that of the psychic texture of the fugitive underground: what it was like to live the life of a Russian novel amid the K Mart realities of America. This is extremely unlikely material for a Hollywood feature film, but the surprising achievement of Sidney Lumet's Running on Empty is that it captures an authentic piece of that untold story with remarkable intelligence and an unexpected emotional wallop—it's got a tearjerker impact as powerful as that of Terms of Endearment.

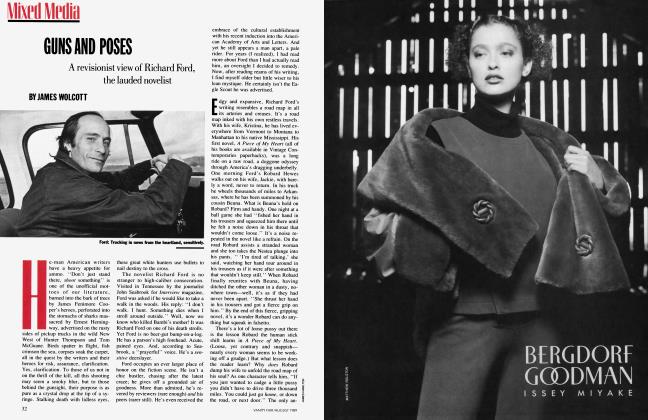

Running on Empty is the story of a couple (Christine Lahti and Judd IlHirsch) who Went Under in 1973 and still haven't come up. And about their son (an impressive performance by River Phoenix), a kid raised on the run who loves his parents but wants to leave that life behind. Both Lumet and the screenwriter, Naomi Foner, took pains to tell me that their fugitive couple is not specifically a Lost Patrol of the Weather Underground. But Foner says her screenplay was inspired by a recent reunion with a close friend who Went Under with the Weather Underground in 1969 and didn't surface until the eighties. They were at Columbia together back then. It was a time which saw a parting of the ways in the protest movement between friends who Went Under and those who stayed behind. She recalls the moment when her friend came by and handed her some personal mementos, part of a process of divesting herself of traces of her old identity before she disappeared.

"I saw her after she came up again," Foner recalls over cappuccino in a Beverly Hills pastry shop. By that time Foner was living a comfortable screenwriter's life, raising two kids. "She had two kids also, a little younger than mine, and she was telling me about what it was like trying to raise them underground. I was enormously struck by that aspect of the story: should a child have to take the burden of the choice that the parents made?"

What is it like to live the life of a Russian novel amid the K Mart realities of America?

Foner's script pulls off the difficult and delicate task of seeing her fugitive couple both critically and sympathetically. "That was difficult, walking that line," she says. "Making it clear that these people acted out of integrity, that this was not a movie about a bad set of parents who had a kid trying to escape to a better world."

Anyone in touch with what is actually going on in Hollywood would probably regard a complex screenplay about radicals who blow up buildings one of the least likely to ever make it into production. And, in fact, there were several major obstacles that had to be overcome.

Producers Amy Robinson and Griffin Dunne brought Foner's script first to Sidney Lumet. It seemed like a logical choice, but Lumet had been burned by this kind of material before. His film of the E. L. Doctorow novel The Book of Daniel (a thinly veiled account of the executed Rosenbergs and their children) had been a labor of love, and he'd been so badly wounded by its cold reception that he hadn't been able to look at the film again until this year.

"In all honesty," Lumet says, "the rejection of it... it hurt me so. I was just devastated by that. And we were right-— they were wrong!" He adds defiantly, "It was a good movie."

Still, to take on another script about notorious radicals and their troubled children required him to defy conventional Hollywood wisdom. He also had to overcome studio rejection. After much dithering over script drafts, Lorimar, with whom Lumet had a development deal, refused to green-light the film, and Lumet exercised a clause in his contract that forced the studio to fund a film it had rejected if he kept the budget under $7 million. (As a result of the recent takeover of Lorimar, Warner Bros, is now releasing Running on Empty.) The film probably could not have been made any other way, Lumet says, because after each successive script draft stage, "they'd tell me, 'Yeah, it's better, Sidney, but there's still too much politics, too much talk! Mention the

politics in the beginning and don't deal with it again.'

"I'm a political animal," Lumet says. "I'm a Depression baby, and if you're a Depression baby you're in politics for the rest of your life."

What makes Running on Empty particularly provocative is the tension between the Depression-baby, Old Left orientation of Lumet and the baby-boom. New Left politics of Naomi Foner.

Lumet has complex critical feelings about the failure of the New Left, although he doesn't seem to think they show. When I asked him about them he said, "Where did you get that from, Ron? It's very true, but nobody's ever asked me that." He professed some respect for the achievements of the New Left: "Let's face it, they stopped a war without overthrowing a government. I think it may be the first time in history that's ever happened." But, he said, they were also in revolt against the Old Left, and "they cut themselves off historically from their roots—it was 'Fuck you guys! Who are the Wobblies? Jimi Hendrix is real revolution.'

But the piece of music that has the most impact in the film is not Hendrix but, surprisingly, James Taylor's "Fire and Rain." Surprising because the song has always seemed to be the epitome of the flabby false sentimentality of the sixties sensibility at its worst. And yet somehow Lumet manages to make it the centerpiece of one of the most genuinely luminous moments in his film.

It's a birthday-party scene. The fugitive family is celebrating Christine Lahti's forty-something birthday, but there's an intruder present. The oldest son has invited his new girlfriend (Martha Plimpton). You can tell there's some uneasiness about this; they're not used to letting outsiders inside their security perimeter, not used to letting down their guard emotionally either. The parents are torn: pleased their son has a serious girlfriend, worried about what will happen to him when, inevitably, they must change their identity and move on. Finally there's a moment after dinner when someone puts "Fire and Rain" on and the girl starts to dance with the father and. . .well, if you'd described this to me in cold print, I wouldn't have believed it would work, but it does; it's a heartbreaking moment.

Sctually, however, the music that captures the edgy urgency of fugitiveunderground consciousness best is not James Taylor or Hendrix but David Byrne's retrospective-fantasy anthem "Life During Wartime." That's the sound track I hear when I recall the one face-to-face encounter I had with the Weather Underground while they were on the run. Well. . .to say face-to-face is something of an exaggeration. They were wearing wigs and dark glasses, and before I could focus on their faces, they put a blindfold on me.

My glimpse of the underground began in a van in the long-term parking lot of the Sacramento Metropolitan Airport. The Weather people had offered the use of their security and logistics resources to transport two reporters—me and Michael Shamberg (later producer of The Big Chill)—to a clandestine interview with an affiliated political fugitive.

It happened that the day I spent in their custody was a significant turning point in the Weather Underground trajectory. It was on that very day that the N.L.F. guerrillas marched into Saigon, on that day that the U.S. ambassador tied from the embassy roof by copter. The war was over; their side had won. The news came over the radio in the van as it made its circuitous way to their safe house. But, oddly, there was no expression of joy, hardly any reaction at all. They'd gone too far under to consider coming back up. The war was over but for them life during wartime wasn't going to come to an end.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now