Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowTHE SECRET TEAM?

MICHAEL SHNAYERSON

Did Ollie North's pals run Covert drug and assassination operations in Cuba, Vietnam, Chile, Iran, and Nicaragua? We'll find out next month in court

Politics

The man is on.

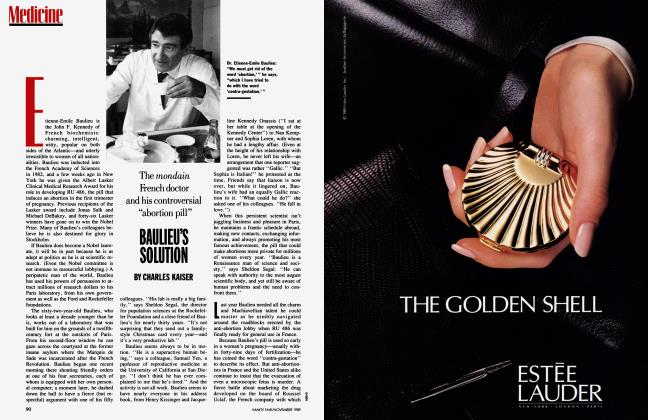

He stands at the pulpit of a Brooklyn church: tall, his untamed curls prematurely gray, his good-looking mug as Irish as they come. To this Sunday-aftemoon crowd of one hundred believers he tells The Story again, the story he tells with missionary fervor in churches and auditoriums around the country. It is a story that begins with Lieutenant Colonel Oliver North and the Irancontra hearings but then ranges back— back in a mind-boggling whirl of Cuban names and perplexing events to the Bay of Pigs invasion, more than twenty-five years ago. A stoiy, in short, of conspiracy at the highest levels, of nothing less than a shadow government of the United States perpetrating a worldwide network of crimes in the burnished name of democracy. "This is a test for the American people," the man concludes. "And the question is: Will they pass?"

He is Daniel Sheehan, fortythree, activist lawyer of the Karen Silkwood case, former Harvard divinity student, co-founder of a Washington-based phenomenon called the Christie Institute. Together with his wife, Sara Nelson—the equally determined-looking woman in the front pew—and a Jesuit priest named Bill Davis, Sheehan built a nonprofit public-interest group that has achieved an astonishing victory. Next month, barring legal delays, it will bring The Story that Sheehan has been telling for so long to a U.S. federal courtroom as a civil suit in the Southern District of Florida, Judge James Lawrence King presiding.

Some of the defendants named in the suit will be familiar from last year's hearings. Retired major general Richard Secord. Retired major general John Singlaub. Former C.I.A. agent Theodore Shackley. John Hull, U.S. millionaire rancher living in Costa Rica. Arms dealer Albert Hakim. Others have surfaced once or twice in the news, then slipped back into the murk. Francisco Paco Chanes. Rafael "Chi Chi" Quintero. Tom Posey. Three government investigations are turning up many of the same names; one has resulted in indictments against North, Secord, and Hakim. But their focus is on the recent past.

The Christie's suit, by contrast, alleges that Iran-contra was no more than the latest caper undertaken by this largely fixed cast of characters (known variously as the Secret Team or the Enterprise). Since 1959, as Danny Sheehan sees it, they have orchestrated private wars and carried out drugs-for-arms and assassination schemes in Cuba, Laos, Vietnam, Chile, Iran, and now Nicaragua.

The charges are detailed and complex, as riveting as a Ludlum thriller and far more disturbing, and Danny Sheehan has drawn his share of disbelievers even among the left. No one can deny, however, that he was among the first to identify Oliver North as a principal character in the illegal contra-funding campaign. The Christie suit was filed in May 1986, months before Attorney General Edwin Meese admitted that North had had something to do with a diversion of money to the contras from Iranian arms sales. With that admission, Sheehan's institute gained overnight credibility.

Nor can critics help but admire the way in which Sheehan has built his case, on the acronym usually associated with Mafia trials: RICO (Racketeer-Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Statute). To the shock of skeptical lawyers and journalists, not to mention the defendants, the Christie Institute presented Judge King with enough evidence of what amounted to racketeering activities by the Secret Team to be granted sweeping subpoena powers—and the chance to prove each of the twenty-nine defendants guilty by association.

But a RICO case must be predicated on damage to a business enterprise. That is why the Christie Institute's civil suit, with its demand for $20 million in damages, hinges on a seeming trifle: the damage done to the camera equipment of an American journalist in a bombing incident in Nicaragua on May 30, 1984.

It was at a press conference in the La Penca contra camp that the bombing actually occurred. There to speak was Eddn Pastora G6mez, also known as Commander Zero, leader of the southern contra front. Initially the C.I.A. had helped him, he said—delivering monthly stipends of as much as $150,000 in cash. Now, though, there was growing pressure on him to join the main contra force. Just before the press conference, a newly arrived Danish journalist casually left a heavy metal camera case by the speaker's table. Minutes later, the case exploded. Pastora survived the blast but was badly shaken; he has since retired from the fray. Eight others were killed, however, and twenty-four wounded.

The whole incident might have been forgotten were it not for the follow-up investigation conducted by one of the injured journalists, ABC stringer Tony Avirgan, and his wife, Martha Honey, an American reporter for the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation and London Sunday Times.

Avirgan and Honey turned up a thick sheaf of evidence implicating not only the "Danish" photographer (whose real name turned out to be Amac Galil, and whose nationality was Libyan) but a millionaire American rancher in Costa Rica named John Hull. Hull filed a libel complaint when the report was released; to defend themselves, Avirgan and Honey turned to Daniel Sheehan for legal advice. When Hull lost the case, Sheehan persuaded them to climb aboard for the trigger RICO suit.

In the nearly two years since, Sheehan has told The Story hundreds of times; it is now being passed on by disciples. In Los Angeles, rockers Jackson Browne and Don Henley have helped raise $250,000. In the heartland, believers have staged house parties—several hundred in Minneapolis alone—at which videotapes of Sheehan telling The Story are shown. Some sixty organizations, from the Presbyterian Church USA to the National Organization for Women, have signed on to get out the word and raise money.

Given all the bell ringing, why hasn't The Story been getting heavy play on the front pages of every major American newspaper?

The morning after his Brooklyn church speech, in a quiet little restaurant on Columbus Avenue, Danny Sheehan offers an answer. Away from the pulpit, Sheehan is mercifully less solemn—boyish even. He's the big kid from the local Catholic high school, joshing with his teammates on the way to the bus. Beaver Cleaver, through and through.

"They know we're not crackpots," Sheehan replies in answer to my question. "They know we were the first ones to tell them about Oliver North. Even so, all they focus on is the next level of activity that hasn't been substantiated, and assume it must be wrong." Furthermore, he points out, editors and publishers hobnob with the same politicians in whose interest it is to keep The Story suppressed; they tend to heed warnings that America's national security is threatened.

Perhaps. But conspiracy theories do have a way of making editors balk. And one which touches on virtually every mystery of modem American politics— from the Bay of Pigs to John Kennedy's assassination to Watergate to the Shah of Iran to the flood of heroin and cocaine entering the U.S.—has struck some as not only pat but paranoid. As Christopher Dickey, author of With the Contras, puts it, "My gut problem with the Christie Institute suit is that the people involved with it started with a fairly fixed notion of conspiracy and then set about fleshing it out."

"They know we're not crackpots. They know we were the first ones to tell them about Oliver North."

Most journalists who have looked into The Story have encountered a source problem. As in: sources not available. It's not hard to believe Sheehan when he says his sources feel seriously endangered and insist on anonymity. Early on, a Nicaraguan who said he had helped John Hull's men plan the La Penca bombing was allegedly kidnapped along with a startled Costa Rican to whom he had told the story; the two were brought to Hull's ranch, but managed to escape. Shortly after, the Nicaraguan, known simply as David X, vanished again and hasn't been seen since.

Steven Carr, another important source, died in California of what the Christies believe was an unlikely drug overdose. Last year, Martha Honey and Tony Avirgan were crudely (and unsuccessfully) framed in a drug bust by the Costa Rican authorities.

Sheehan has given sources to journalists he trusts, however. One is Leslie Cockbum, whose much-noted television reports on West 57th and recent book, Out of Control, corroborate Sheehan's views. Another is Dennis Bernstein of WBAI radio in New York, whose daily

"Contragate" reports have been balm for believers. Reluctantly, Sheehan has also now divulged sources to the defense; Judge King stood ready to throw the case out if he didn't.

Even so, an oft made point is that the Christie's theories about the La Penca bombing are based on the testimony of a man none of the plaintiffs has seen. Perhaps this "David X" never existed at all.

"I talked to him a number of times on the phone," Martha Honey says firmly from Costa Rica. "Tony saw him from a distance, and we have a voice recording. Also, contras we know here have interviewed him."

Sheehan goes further, ticking off names and connections that start to assume a murky and mesmerizing reality of their own, like characters in some flickering home movie. Mercenaries who worked briefly for Hull and later talked about it. A former Costa Rican narcotics official who testified to seeing Hull with hit man Amac Galil (and the telltale camera case) boarding a boat to go to La Penca. A member of the Miami underground who was recruited by Hull to stage a similar bombing raid on the American ambassador to Costa Rica—to provoke the U.S. into full-scale war with the Sandinistas.

The more evidence gathered, though, the fuzzier it tends to get.

Sheehan hasn't helped matters by declaring, when pressed, that he's only 80 percent sure of some of his charges. Or by acknowledging that his original affidavit contains errors, and that the whole of it is based on hearsay.

There's nothing wrong with that—from a lawyer's point of view. A lawyer in any civil case initiates his case on reasonable faith, then spends the "period of discovery" up until the trial gathering evidence. In a civil suit, moreover, the jury need be convinced only that the lawyer's case is more right than wrong. But Sheehan comes across as fire-and-brimstone preacher, rather than lawyer, and the audiences who soak up his powerful pulpit rhetoric tend to assume it's gospel.

Even Honey and Avirgan are uncomfortable with Sheehan's decision to balance the big picture atop their carefully researched La Penca story. "The centerpiece of the case—an off-the-shelf covert team running the war in Costa Rica with arms and drugs and terrorist trafficking—is absolutely true," says Honey. On the rest, "we appreciate the Christie's effort to raise public consciousness, but I think frankly that Danny should be more careful, when he deals with journalists and community groups, to say, 'This is good enough for the courts but not for you.' "

Grayest of the gray areas may be the 1960s Laos/Vietnam period. The Christie's suit has it that after botching the Bay of Pigs invasion and several follow-up assassination attempts against Fidel Castro (including exploding cigars), the Secret Team of C.I.A. operatives and Cuban-Americans turned its attention to Southeast Asia. Among those involved: Air Force Lieutenant Colonel Richard Secord, General John Singlaub, and a young Naval Academy graduate named Oliver North. Interestingly, North is not a defendant. Sheehan says he doesn't want to get entangled in the issue of whether North is protected by immunity; others see this as a grave omission—going after the gang but not the gang leader.

Sheehan says the Secret Team carried out 160,000 assassinations in Southeast Asia. Thereafter, various members went to Chile to topple Salvador Allende ... before heading over to Iran to prop up the shah. . . before going underground in the Carter years to prop up Somoza.. .and so on to the present.

A spluttering General Secord says that his C.I.A. work in Southeast Asia was confined to "hauling rice and bullets." But Secord's integrity has been badly impugned, not least by the revelation that he paid one Glenn Robinette more than $100,000 to dig up dirt on the Christies and their case in 1986.

General Singlaub voices the more persuasive protests. Fervently anti-Communist, he comes across as a general of the Patton school: fearless, crusty, utterly candid. Even before the Boland Amendment outlawed contra aid in 1984, Singlaub had taken the contra cause around the country, raising funds as a private citizen for what he termed humanitarian aid. After Boland went into effect he became, by his own definition, a "lightning rod" for Oliver North's covert campaign, an easy way of explaining to pesky journalists why Nicaragua-bound planeloads of supplies continued to fly into El Salvador's Ilopango military airport. But as for the charges laid against him in Sheehan's suit—well, let the general speak.

"The Christie suit is fiction," he says in a booming voice via the speakerphone in his lawyer's office. "And it's not even good fiction. It's bad fiction."

Was Singlaub aware, at least, that North and others were engaged in illegal arms shipments during the Boland Amendment?

"No. I never suggested that North reveal any information to me. Only those who have a need to know should be informed. That's a fundamental principle here."

It's also Singlaub's defense against any Rico charges of guilt through mere association. Even the strictest reading of Rico, says his lawyer, shouldn't suggest that merely knowing a defendant constitutes guilt. "Otherwise you'd have a daisy chain thousands of people long."

When all the details of the case have been debated, all the charges met with countercharges, there's one last nasty little doubt that lies beneath them: Is Daniel Sheehan a well-intentioned dogooder? Or is he just a glory hound?

From the defendants and their lawyers, of course, one hears phrases like "irresponsible lunatic." Less expected are the digs from left-wing sources like Mother Jones magazine, whose recent, unusually harsh story concluded that Sheehan is "a brilliant publicist with more than a shadow of the huckster. ' '

Others rush to Sheehan's defense. Says "Contragate" 's Dennis Bernstein, "You do need a lot of confidence to take on the U.S. government and its covert operators, who number in the hundreds of thousands. But, personally, I've always found Sheehan to be a straightforward, down-to-earth guy concerned with doing what's right."

There may be truth in both readings.

A small-town boy with a strong sense of justice, whose father was a prison guard, Sheehan also felt patriotic enough to enroll in an R.O.T.C. program at Northeastern. The program changed his life. Instead of standard military skills, Sheehan found himself learning how to sever an enemy's head with a piano-wire garrote. Told that his enemies would certainly include women and children, Sheehan angrily resigned; the next year he transferred to Harvard, and stayed on, with a full scholarship, through Harvard Law.

"He probably took more than his share of airtime in class," recalls fellow student Joseph de Raismes, now city attorney of Boulder, Colorado. "He wasn't necessarily liked, but I don't think Danny's ever cared about being liked."

Sheehan's first job was with the New York firm of Cahill Gordon & Reindel, where he served as one of twelve lawyers representing The New York Times in the Pentagon Papers case, along with Floyd Abrams and Alexander Bickel. He had been promised he could do considerable pro bono work, but when his client list grew to include Black Panthers, conscientious objectors, and prisoners from the Tombs, the firm began to object. "He ended up doing almost exclusively pro bono work," says Abrams, "and occasionally declining to work on my client matters. Usually my role in these interviews is to confirm that Dan Sheehan was fired—so, yes, that is true—but that was really because there was no fit at all."

Oddly enough, Sheehan's next bounce was to F. Lee Bailey—a lawyer not known for taking pro bono cases. The Bailey job lasted all of one year.

Disillusioned, Sheehan enrolled at Harvard Divinity School. Soon, though, came a call from de Raismes, out at the A.C.L.U.'s Mountain States Regional Office: did Sheehan want to help defend the protesters arrested at Wounded Knee? Sheehan did. That led to defense work for the Berrigan brothers and comedian Dick Gregory. And then, in 1976, to the Karen Silkwood case.

Sheehan offered to represent the Silkwood family for free. The case gained national status, and Sheehan, as chief counsel, rejoiced when the jury found the Kerr-McGee Corporation guilty of negligence in allowing a deadly quantity of plutonium to mysteriously end up in Silkwood's refrigerator.

The negligence suit, however, was only half the case; the other half, which charged Silkwood had actually been murdered, was not allowed to be heard. That was Sheehan's half. As a result, only the flamboyant Gerry Spence, brought in to handle the negligence suit, represented the case in court. At the time, Sheehan was seen by some as trying to yank the limelight in his own direction. Spence good-humoredly confirms this: "Danny is one who has never been bitten by any.. .let's call it 'humble bug.' So it was often difficult to determine from the press who tried the case. I don't mean to disparage him in any fashion. He's trying to do good. And I think," Spence says, weighing his words carefully, "he is sometimes successful at that."

It was during the Silkwood case that Sheehan met and married Sara Nelson. With the case concluded, the two decided to form an "interfaith public-interest law firm and public-policy center" to take on more civil suits. They named it after the Jesuit philosopher Teilhard de Chardin's concept of a nonsectarian Christie Force—a sort of developing sixth sense of harmony in the human race.

That dream is now a $3-million-a-year organization with nearly sixty full-time employees. Still, the scene inside the three dilapidated row houses that lie only a mile from the Capitol is straight from the sixties: blue-jeaned staffers collating piles of press releases, manning phones in scruffy rooms papered with broadsides for political rallies. A real sense of danger hovers in the air. "We do worry about the phones' being tapped," says the Christie's Sally Schwarz. "And just the other day a very strange-looking antenna appeared on top of a building across the street. A vacant building."

Sheehan found himself learning how to sever an enemy's head with a piano-wire garrote.

Pumped up by the case, the Institute would seem destined to deflate once a verdict is returned. But Sheehan and Nelson say winning their suit would be only the start. In the Columbus Avenue restaurant, breakfast dishes pushed aside, Sheehan speaks in earnest of forcing a reassessment of America's foreignpolicy methods and, more immediately, of impeaching a president who unquestionably knew what his Secret Team was up to. In legal terms, he says, this is a president who participated in a criminal conspiracy to violate the federal Neutrality Act, engaged in Arms Export Control Act violations, engaged in currency violations, engaged in a conspiracy to obstruct justice. "If this is allowed to stand, there's not any doubt that the next president is going to cite it as a precedent."

What I wonder, as the names and details wash over me, is how things have gotten this bad. Sheehan's answer is somehow more convincing proof than any litany of facts that the man is, if not humble, if not 100 percent correct in his charges, still on the side of the angels.

"How many times did you play highschool football and like the other team's halfback?" he says. "You have no sense of that player as a person. And even if one of your guards is biting in the pileups, you don't say anything about it. Every time an offsides is called against one of your guys, you don't believe it. That's the quality of this administration. They think passing interference is O.K. as long as you get away with it. When I was playing football in high school and college, I couldn't believe it when someone did something like that. I would become livid. That concept of justice, of fair play, is what's driven me for so long. You can't do this kind of stuff."

I t's with those words echoing that I fly I down to Washington to hear the depI osition of a major figure in the case: Oliver North's faithful courier, Robert Owen. Owen made several trips to Central America to deliver bags of cash to contra leaders and come back with "needs lists." Each time, he met with John Hull, and was with him the night of the La Penca bombing.

The deposition has already begun when I arrive. In a plain, whitewalled conference room, a dozen participants are gathered. Owen sits at the head of the table, a tall—six-foot-three—preppy-looking character in his mid-thirties with the demeanor of a hurt patriot. He shoots the cuff of his pink dress shirt to reveal a script monogram. Restless, he wraps his big black shoes and yellow argyle socks around the legs of his chair, and slides off his gold watch to play with it on the table.

Only a handful of observers are lined along the wall. All are lawyers, it turns out, except for one reporter from the Providence Journal-Bulletin, who's gained his editor's go-ahead largely because Owen is from a socially prominent Rhode Island family. The talk is of tapes made by Joseph Kelso, a U.S. Customs informant—just one of The Story's myriad subplots. Kelso apparently gleaned ample evidence in mid-1986 that drug and terrorist operations were being conducted from Hull's ranch with the active help of corrupt Drug Enforcement Agency investigators. Kelso says Hull got wind of this, and had him arrested by Costa Rican authorities and brought to the ranch. Later released, Kelso turned the tapes over to his superiors with strict instructions not to let them go to Washington. Somehow Owen learned of the tapes and secured the only copies. In late November, Owen and his wife moved to a new home; the tapes, Owen says, somehow vanished in the move.

"Did you ever make any attempt to find out what was on the Kelso tapes?"

Owen tips his chair back on its legs and balances a moment, his big hands resting on the table's edge. "To the best of my knowledge, no."

All the same, Owen does admit that the Christie Institute's lawsuit worried him from the start. Worried him enough to take an interest in the Kelso tapes. Worried him enough to meet with Glenn Robinette about the case as many as fifteen times.

"And you knew, didn't you, that Robinette's specialties were eavesdropping, wiretapping, and falsifying documents?"

Owen shrugs.

"And were you assisting Robinette in his investigation of the Christie Institute lawsuit? Or was he reporting to you?' '

Owen hesitates. "Both."

A little before noon, the lawyers agree to a short break. The stenographer gets up from his machine. The videotape operator flicks the monitor off.

One by one, the others file out: the principal lawyers, the lawyers along the wall, the single reporter. And then suddenly, unexpectedly, there's no one left in the room but Rob Owen and myself.

Owen plays with his watch. I pretend to take notes. The silence grows and grows. How strange to be here. With this man who, perhaps more than anyone but Oliver North, knew the extent of the White House's covert war in Nicaragua. How does a straight-arrow graduate of Stanford who proposed to his wife on the steps of the Jefferson Memorial on the Fourth of July end up here?

That's what I want to ask him—and if there's anything he'd change, any regrets. But I don't have the nerve, in this airless room, to do that, and, anyway, I know what he'd say: no, he has no regrets, certainly not about the principle of an off-the-shelf covert operation to circumvent the lily-livered liberals in Congress. That I can sense in every answer he gives, every grimace, every shrug. There are two American philosophies today, and each is as stubborn as the other.

Finally the door opens, and the lawyers file in and take their seats. The videotape operator starts his camera. The stenographer sits with fingers poised on his keys. And then the lawyers start in again, and the case—the case that Danny Sheehan made happen—grinds on.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now