Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowEditor's Letter

Dance of Death

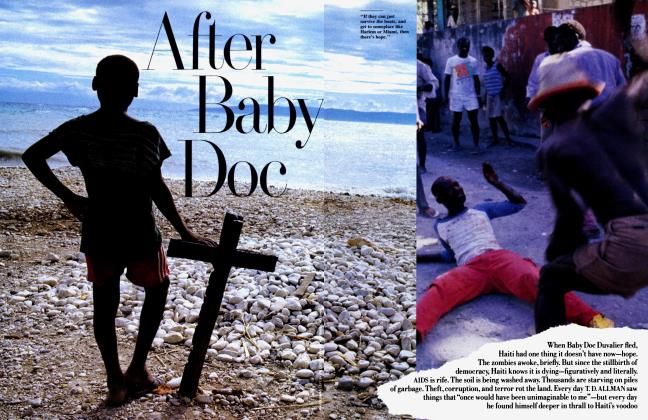

Vanity Fair's foreign correspondent T. D. Allman nearly didn't come home from Haiti. It wasn't the physical danger, though that was always present. It was simply that he was hypnotized. His absorption in the extraordinary psyche of a doomed country was so total that he was drawn deeper and deeper into its bizarre dance of death. When he finally returned to the United States, it was with a harrowing perception of a land of zombies where AIDS is rampant and a deadened people is ruled by serial dictatorships that kill with impunity. Papa Doc is dead and Baby Doc is gone, but Papa Doc's other children are everywhere in the generation of Haitians he corrupted. Allman documents how the spell is maintained.

Haiti's misery is the principal product of its government, a kleptocracy. At a beach party given by Colonel Acedius St. Louis for the military elite, Allman meets some of the country's most powerful thieves. The latest strongman, General Prosper Avril, appears with mistress and retinue in tow. A killer pays a courtesy call, in formal dress, to ensure his

standing with the men who matter. And Allman sees the effects of the military's arbitrary life-anddeath power when one of his host's minions risks drowning to avoid displeasing his boss. Except that life and death are virtually indistinguishable in Haiti. Even the most educated, Westernized Haitians harbor a fundamental belief in the voodoo spirits. It has, Allman suggests, infiltrated even the U.S. Embassy.

The report he files conveys the power of Haiti's magic and the nature of its pain: "Haiti is to this hemisphere," he writes, "what black holes are to outer space."

Allman has had long experience reporting from abroad—Cambodia, El Salvador, Ethiopia, and most recently the Philippines and Panama for Vanity Fair. In Haiti, he found little that corresponded with any reality he'd encountered before.

Editor in chief

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now