Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowEditor's Letter

The Ghosts of Munich

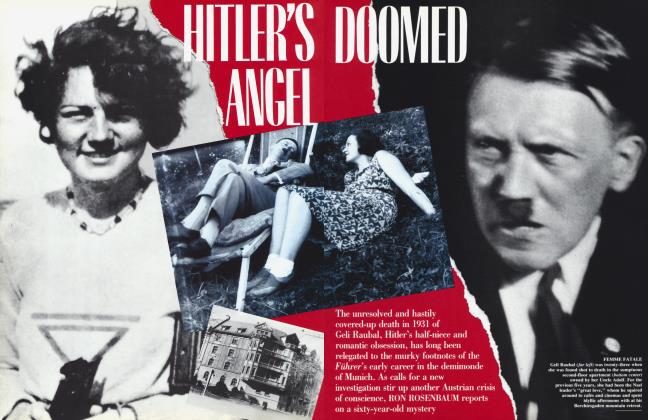

On September 18, 1931, twenty-three-yearold Geli Raubal died a few steps from Adolf Hitler's Munich bedroom, a bullet through her chest, his 6.35-mm. Walther pistol by her hand. She had been his halfniece, his doomed amour passionnel, "a tabooed love of Tristan moods and tragic sentimentality," according to one German historian. Her death, hastily ruled a suicide, was more devastating to Hitler than almost any other event in his life, and ever after, he kept a bust of Geli in his bedroom and fresh chrysanthemums in her perfectly preserved chamber. The nature of his obsession with her remains controversial—as are the circumstances surrounding her death. It was but one of millions to come, one which may provide a window into the depths of his psyche.

A 1931 German newspaper said the truth about Geli's last moments in Hitler's apartment was obscured by a ''mysterious darkness." Sixty years later there is, as Ron Rosenbaum reports on page 178, a new campaign to penetrate that darkness by exhuming Geli's body and reopening the case.

Geli Raubal was an attractive seventeen-year-old when her Uncle Adolf summoned her to serve as his housekeeper in Munich. He was, at the time, a rising political figure presiding over an eccentric demimonde peopled by what one early biographer called ''armed bohemians"—pimps, con men, occultists, petty thugs, and sexual outlaws. For five years, he proudly squired her around to cafes and theaters and paid for singing lessons. In public, she became a celebrity, his consort, the envy of countless women. But in private, Geli was a virtual prisoner of Hitler's possessive jealousy, tormented, according to one school of historians, by the aberrant nature of his sexual needs. On the last day of her life, she and Hitler had a heated quarrel, apparently over her desire to escape him. The next morning, she was found dead.

To some, the official verdict of suicide is no more credible than the Warren report's conclusion on who killed J.F.K. If there was nothing to cover up, if Geli had really killed herself because of ''stage fright," as the official story had it, why did Hitler's henchmen prevent a thorough autopsy, derail the police inquiry, and quickly spirit the young girl's body off to be buried in her hometown of Vienna? To find the answers, Ron Rosenbaum searched through archives in America and Europe and tracked down surviving witnesses in Munich and Vienna, resuming the scandalous murder investigation that was suppressed sixty years ago.

Editor in chief

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now