Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowSOCIAL STUDIES

The Goya blockbuster, now at the Metropolitan Museum in New York, redefines "society painting"

MARK STEVENS

Art

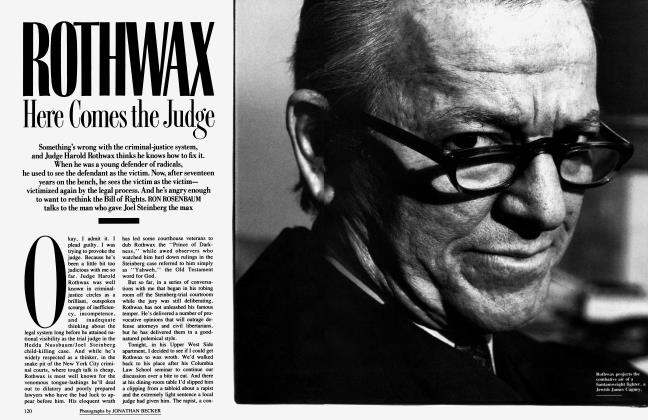

'Society painter" usually means a smoothy with the brush, a flatterer adept at rendering pearls and power. Understood another way, however, the term could mean an artist who conveys the character of an entire society. Today, for example, many people think Andy Warhol did both things, revealing the heart of a media-saturated, celebrityobsessed culture even as he flattered the rich. The gush over his recent exhibition at New York's Museum of Modem Art calls for at least a glance at what a really great "society painter'' can do.

Like Warhol, the Spanish painter Francisco Goya (1746-1828) portrayed both the fancy names and the popular culture of his day. He, too, defined his age.

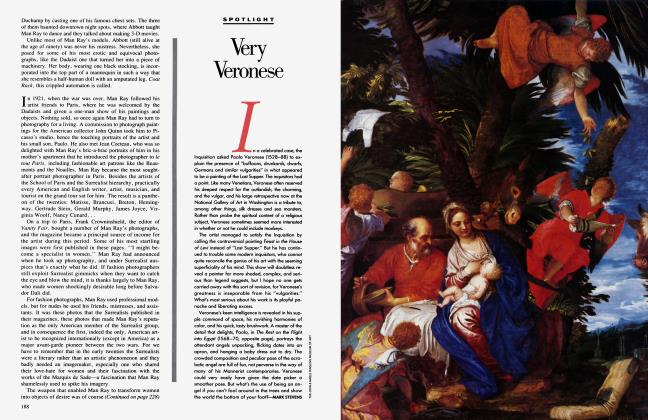

But unlike Warhol, who made himself indistinguishable from the moment, Goya always challenged his culture and rose above the times.

A passionate partisan of the advanced, or "enlightened," thought of the period, Goya was part of the movement trying to reform the backward church and aristocracy and bring about a more rational and humane society. An exhibition celebrating this aspect of the painter's art, "Goya and the Spirit of Enlightenment," is now at the Metropolitan Museum in New York after showings in Boston and Madrid. In certain ways, the show is misleading (about which more later), but it does successfully highlight Goya's involvement with the struggles of his day. If that sounds merely political, it isn't, really—because Goya was never just a spokesman, tractarian, or message-monger.

He became a painter to the king in 1786, during the reign of the enlightened Bourbon monarch Carlos III, and took full advantage of the position, portraying the high society of his time—royalty, aristocrats, important government officials. A court painter must be very good at showing off clothes (what's wearing the clothes is usually much less interesting), and Goya understood this fact of life. He liked to paint his pictures in the morning and then, later in the day, he would put on a hat ringed with candles to add the finishing touches in the light in which most of his society pictures would be seen. He had a way of daubing drips of paint across the surface in a crusty, uneven impasto; the flickering of candlelight must have made it sparkle on the dresses like a scattering of jewels.

What's truly remarkable, though, is how subtly Goya renders the people inside the clothes, particularly the women. Warhol's celebrity portraits are all very much the same because he is portraying the celebrity, not the person. Society painters of Goya's day also, typically, portrayed the rank instead of the individual. However, when Goya painted expensive women, he did not surrender to such generalizations; nor did he push any idea about "the fair sex," "the duplicitous sex," or the like. Every woman is herself, whether whorish, vapid, smart, delightful, vain, or stylish. Even when he turns an airy concept into a woman (as in his allegory of the constitution coming to Spain), the figure does not strike one as merely abstract: a young woman steps forward, somewhat tentative and awkward, but open-armed with hope. Most unusual of all is Goya's willingness to portray intelligence in a woman.

The Duchess of Osuna, for example, was an important patron who came from an influential Spanish family. The duchess insisted upon raising her children herself, and she and her husband went to great lengths to encourage those people at court who wanted to bring some sense to privilege. Goya painted her splendidly attired— that goes without saying—but the viewer does not really accord the froufrou or the dopey little lapdog much importance. In one family portrait, the children have gathered around rather informally. The duchess meets the painter's penetrating eye with a certain authority, but also without any pretentious posturing. The painter plainly admires her, less as an aristocrat than as an equal.

By contrast, Queen Maria Luisa is so superior she's inferior. The queen was famous for her vanity and love of luxury; she forced women in her company to wear lace of such expense that many families were actually brought to ruin. She also forbade the use of long gloves because she was so proud of her arms. In Goya's portrait, she is dressed in a spectacular concoction of black lace finery and one long naked arm shimmers against the darkness. Goya accentuates her rank by making the viewer look up to see her, and the queen strikes what she doubtless thinks is an august pose. Alas, she is a bovine creature with the shrewd eyes of a village gossip. The acreage of black lace, while brilliantly rendered, looks as sticky as a spiderweb, perhaps Goya's acknowledgment of the debilitating effect on Spain of an exaggerated taste for luxury.

The society portraits even evoke the complexity of palace intrigue. In addition to the queen, Goya portrayed her lover, Don Manuel Godoy, whom she had plucked out of the Horse Guards and promoted until he became the most powerful man in the country. He is shown lazing back, resplendent in uniform, after a battle with Portugal. He seems to have supped on victory. To accent his power, the aide who is peeking out from behind the great man's shoulder resembles a timid deer. Godoy himself is a corpulent bull, powerful but overstuffed: the blood in his face looks thick with self-satisfaction. (It is easy to see why the queen, a middle-aged coquette, found him sexy.)

For social reasons, the queen had married Godoy off to a convent girl from a fancy family. Her picture is also in this exhibition, and one hates to think of her marriage to Godoy, for she appears to be everything he is not. Delicate, sensitive, a little bewildered, she seems to weigh hardly more than a feather even though she is pregnant. The picture displays such tender sympathy for the girl that it is almost painful to look at her. Goya has placed her in a large and darkly shadowed space from which her seated figure seems to emerge like a small light of white and gold.

In a letter of about this time, the greatest intellectual of the Spanish Enlightenment, Gaspar Melchor de Jovellanos, wrote that Godoy had invited him to a dinner party at which he was actually seated between Godoy's wife and lover (not the queen). "This spectacle filled me with sadness; it was more than my heart could bear. I could neither speak nor eat nor think straight; I fled the scene." Not surprisingly, Goya's portrait of Jovellanos, as a government minister weighed down with the work of enlightenment, is sympathetic. There's a complicated pucker to his mouth that seems partly genetic, partly an exasperation with the world's foolishness, and partly the result of years of screwing up his face in intense concentration.

Goya intended to expose many of the horrors that the Spanish Enlightenment hoped to correct: corrupt clergy, lazy aristocrats, the appalling condition of the poor.

This is not the usual sort of society painting. Goya made distinctions of intelligence, not simply of rank. There is nothing programmatic in his response to a sitter, and his judgment always seems subtle, shaded. When examining his feelings of social anger, it is important to remember his respect for reason. His earlier prints, such as the series "Los Caprichos," had a didactic intent well suggested by the most famous of them all, called The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters. He intended to expose many of the horrors that the Spanish Enlightenment hoped to correct: corrupt clergy, lazy aristocrats, inhumane prisons and asylums, the appalling condition of the poor. The prints are almost diaristic in their wide-ranging subject matter and in the messages, often full of wordplay, that Goya wrote upon them.

It is amusing to see an ass with long ears admiring his family tree in a book containing pictures of all the ancestral asses, or to observe a doctor donkey with a ring on his hock taking the pulse of a patient in a print that asks, "Of what illness will he die?" But Goya's greatest gift was for outrage. He brought a beautiful, hands-on roughness to the making of prints. Taking the subject of child abuse, for example, he portrayed a grotesque old man pumping the legs of a naked boy, using him as a kind of farting bellows to fan the flames of lust. Other children await their turn.

While Goya addressed universal themes of this kind, no abstract idea ever led him by the nose. The prints are particular in feeling—they come from the inside out. Warhol's silkscreens, by contrast, look vague, general, imprecise. He portrayed the electric chair, car crashes, sensational crimes, but not so one reacts with anything more than the numb nodding that comes from seeing too much violence on TV. You could say that that's just the way it is nowadays, but you can be certain people were also telling Goya that the poor will always be with us and that one beggar looks like another.

Because the Goya exhibition stresses his relationship to the Enlightenment, it does not include some of his other important work, such as pictures of bullfights and the two famous paintings of the clothed and the unclothed maja. In particular, it downplays his blacker side. We do not see the Third of May or the terrifying visions in the "Black Paintings." We might think, reading the wall panels about the prints, that Goya was still trying to correct social ills in the later work. Perhaps, but he had a much more intimate relationship with the monstrous than the exhibition suggests.

Barbarism, shattered hopes, and cruel betrayals characterize Spanish history of this period, and only a Candide could sustain much hope for humanity under the circumstances. In a fairly late selfportrait, Goya, whom a serious illness had left stone-deaf, shows himself gasping in the arms of a doctor. It is tempting to regard this as a portrait of reason ministering to despair—and, in looking at Goya's tormented face, to suspect that the patient was losing the battle, that, closed off from the world by illness, he was succumbing to the terrors of the imagination. From the first, Goya's art had a strangeness even when most playful; a darkness is usually present, threatening to usurp the picture. You can see this in many of his formal methods. For example, he liked to paint figures lit from behind, so that their front is touched with shadow.

Toward the end of his life, Goya was not simply portraying darkness so that the forces of light might correct the mistake. Usually he was just bearing witness. The refusal to soften his message with religion or any kind of sentimentality has led many people to call him the first modem artist. But there is one important difference. Even if Goya yielded to despair as he grew older, the hopes aroused by the Enlightenment give his art grandeur. His work has an epic quality in which light and darkness do battle. Today, almost three centuries after the beginning of the Enlightenment, "society painters" have not experienced this secular faith in reason. They cannot provide that high drama.

So it is painters like Andy Warhol who define our period. Warhol's genius lay in graphic design, which should not be scoffed at; but, like the great posters, his pictures repay a glance rather than a look and lose too little in reproduction. He was a kind of brilliant mirror, glinting with the shininess of the parties, celebrities, and all-round pop of contemporary culture. It may be the fault of his times, but there is a sameness that runs through Warhol's oeuvre that glazes the mind; everything takes its character (whether Liza or the electric chair) from the media. I don't like the passivity, the refusal to discriminate, the inability to confront the demons below the surface. An artist can resist, as well as reflect, his time.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now