Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowDOOM AND BLOOM

It's not easy being Allan Bloom in a world full of Simpsons

JAMES WOLCOTT

Mixed Media

Black? Maybe Bart's Jewish. But we're getting ahead of ourselves.

Used to be, pop culture was a smart-aleck voice at the rear of the room—a transistorized wisecrack. Now it's at the head of the class, running the show, rewriting the curriculum. (Roll over, Beowulf, and tell Dostoyevsky the news.) Not that the deposed professors haven't been able to counterflak. With the surprise success of The Closing of the American Mind, which blew taps from the campus tower over creeping shadows, Allan Bloom found himself at the forefront of old-fogy ism. Once it was clear the book wasn't budging from the best-seller list, his critics ballooned. A professor of social thought in Chicago, Bloom was reviled as the Robert Bork of the humanities, harking back to old restraining orders. To Third Worlders, he was a paleface. To deconstructionists, he was a textual dinosaur. To pop theoreticians, all three of them, he was a party pooper trying to unplug the jukebox. Small wonder Bloom ruefully observes in his new collection of essays, Giants and Dwarfs (Simon and Schuster), "I am now even more persuaded of the urgent need to study why Socrates was accused." Because, hell, they may be coming for me next! But he admits being in the spotlight isn't unsexy. ''I have gotten a great kick out of becoming the academic equivalent of a rock star." That's him in the toga, playing air lute.

As an educator Bloom could hardly fail to identify with the Socratic ideal. But where Socrates had upturned aspirants popping questions from the peanut gallery, Bloom is surrounded by fallen arches. ''I feel sorrow or pity for young people whose horizon has become so dark and narrow that, in this enlightened country, it has come to resemble a cave." (With a TV blaring in the corner.) I believe it's Bloom's almost touching avuncular concern which accounts for the sympathetic attachment readers felt for The Closing of the American Mind, and it may extend to Giants and Dwarfs. It certainly isn't the corralbusting quality of his analysis.

Much of Bloom's aversion to intellectuals' avid embrace of din and disarray is an attitudinal replay of his friend Saul Bellow's. 1971 essay in Modern Occasions that argued that modernism had become a bunco game run by clever swingers... a cocktail party masquerading as Armageddon. '7/—civilization— is a failure," wrote Bellow, "but they— the publicity intellectuals—are doing extremely well." Despite his reputation as a cautious crab, Bellow can be an unbelievably hip writer when he unwinds. It was in that same essay that he cracked, after quoting some blather from the Partisan Review, ' 'One of the nice things about Hamlet is that Polonius is stabbed." Compared with Bellow (who wrote the foreword to The Closing of the American Mind), Bloom is slow, painstaking, square. He mellows before our eyes like a pear, in what he calls "the gentle light of great books."

Bloom finds gentle light in strange places. Giants and Dwarfs takes its title from Jonathan Swift, an unlikely candidate for Miss Congeniality. In an essay on Gulliver's Travels, he converts Swift into a closet humanitarian, scowling on the outside, smiling on the inside. "His misanthropy is a joke," writes Bloom, a tactical device. Not so, argued the critic Marvin Mudrick. "Gulliver's Travels is often a mean-spirited and dreary diatribe against whatever Swift disliked, and he disliked many things that most of the rest of the human race finds interesting, attractive, absorbing, virtuous, useful, necessary." But Bloom often seems fond of bland assertion. His essay on The Merchant of Venice begins, "Venice is a beautiful city, full of color and variety." Well, blow me down. He also records tributes to teachers and beacons of liberty such as the late Leo Strauss and Raymond Aron, whose togas have been retired.

By the end of Giants and Dwarfs, he has resumed his plaint. O, the youth of America, how they've withered. "Every year their souls are thinner from want of spiritual nourishment; their openness becomes emptiness, the soil within incapable of sustaining any deep-rooted plant.'' They're ugly too. "One of the ugliest spectacles is that of a young person who has no awe, who is shameless, who does not sense his imperfection.'' Admittedly, I'm quoting from an essay originally published in 1967, when things were pretty hairy. But Bloom has kept up the despondency.

What unites a neoconservative like Bloom with his nemeses on the left is the belief that America has traded in its democratic soul for a demographic breakdown. Instead of the town meeting, we mass at the shopping mall, no longer citizens but bugeyed consumers. The ruddy glow from our cheeks is gone, our pioneer spirit in mothballs. Families float by like fat globules.

But as Steven Spielberg has shown, suburban windows can frame wonders. Fireflies are the fairies of backyard adventures. Unlike the fireflies, kid esprit can't be bottled. On skateboards, kids ride the concrete surf to the roar of Walkmans. Right now no one totes a skateboard like Bart Simpson, man. As Mia Farrow says in The Purple Rose of Cairo, "He's fictional, but you can't have everything."

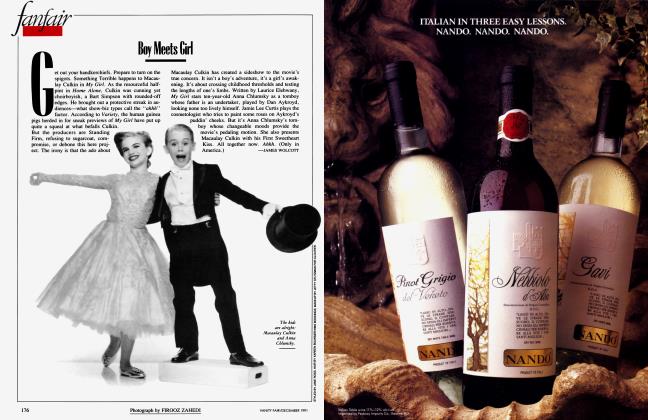

Created by Matt Groening, Fox Television's cartoon smash The Simpsons is set in a Spielberg toy suburb. Its perspective too appears astral. At the opening of each episode the clouds part and a heavenly choir announces, "The Simpsons..." Only when the camera pans down to the twin towers of a nuclear plant do we cotton on to the idea that those clouds may be toxic. Certainly Homer Simpson, who works at the plant, is no model of competence. "This place could blow sky-high," he thinks when offered a promotion to safety inspector. Where Bloom makes an august tragedy of America's abdication to second-rate status, The Simpsons treats it as a necessary comedy. We've had our time on top. Let's just roll downhill awhile, take a breather. If anybody embodies the country's inability to be mean and lean, it's Homer. "I'm a whale," he moans as the bathroom scale reaches 239 pounds. His wife, Marge, whose tall blue hair tips like a tree, assures him that he's still her huggy bear. Nights, they ruin their eyesight in front of the TV with their offspring, Bart, Lisa, and baby Maggie. It's a family portrait that now stares out at us from a million T-shirts.

It's amazing how swiftly the Simpsons have become a national institution. And the show's popularity keeps building. This fall Simpsons merchandise floods the stores as Fox pits the series against Bill Cosby on Thursday nights. Which is canny programming, considering that blacks have adopted and adapted Bart as a brother, emblazoning him on bootleg T-shirts as dreadlocked Rastabart, Nelson Mandela's buddy, etc. Cosby's paternalism may be tired, even with black audiences. The Simpsons has also picked up political adherents. It's been applauded on the left by Michael Kinsley, on the right by Dorothy Rabinowitz. To Rabinowitz, unraveling the secret of the show's success is a snap. ' 'The truth is that every longterm television success has always been wholly understandable, the roots of that success obvious. Viewers' tastes hang on altogether graspable matters such as a good story, the appeal of a character, even— dare one say it?—good writing." Oh, go ahead, Dorothy, dare. Yet I think she trusts too much in sweet reason. When a comedy captures a country as schism'd as ours, rolling across racial and class lines, something deeper and more dormant is being reached. Some pop phenomena aren't attributable totally to talent. Some partake of myth. Or at least archetype.

When a comedy captures a country as schism'd as ours, rolling across racial and class lines, something deep is being reached.

The key, of course, is Bart. Some critics have complained that the show doesn't focus enough on his sister Lisa, who's smart and applies herself. Although she has an impetuous side, twirling flaming batons behind a South Seas mask at the school pageant, she's basically a goody-goody. Bart is a goodybaddy. He pulls all the standard pranks. He orders a spy camera through the mail and takes embarrassing pics. He phones the bar that Homer frequents and asks, "Is A1 there.. .A1 Coholic?" He even drops a cherry bomb down the toilet. "What can I say? I got a weakness for the classics." He's more than the resourceful, irrepressible spirit of play. He's America in short pants. The Good Bad Boy, declares Leslie A. Fiedler in No! In Thunder, is America's summertime vision of itself.

But there's a sad-sack aspect to Bart, which Groening and company are careful not to overdo. Bart is far from the ugly spectacle Bloom deplores in upstart youth; he possesses shame, awe, and a sizable sense of imperfection. Feelings of inferiority are drummed into him from above. Homer preaches to his son a creed of conformity. He reminds him that the code of the schoolyard is "Always make fun of those different from you" and "Never say anything unless you're sure everyone feels exactly the same way you do." School authorities label him an underachiever, a future failure—in short, a loser like his father. But Bart, with his shopping-bag head and fast mouth, is a bom nonconformist. He belongs to the lonely ranks of the easily bored and the hard to fool. What makes Bart a hero, lifting him above Dennis the Menace mischief and Charlie Brown schleppiness, is that he hoists himself above his limitations. He doesn't choke in the clutch.

Beaten daily by the school bully, he organizes a militia. (The episode quoted Patton, with an image of boy soldiers marching across the reflection of Bart's sunglasses.) Worked like a mule by a pair of peasants, he heroically bursts into French to alert a gendarme, nay, all of France, to antifreeze contamination in their wine. ("Vive le Bart!!" proclaims the cover of Newsweeque.) And with Lisa's help, he hog-ties their baby-sitter, an escaped hoodlum whose mug shot appeared on "America's Most Armed and Dangerous." The Simpsons packs just enough gunpowder to prevent these triumphs from being mere soap bubbles. They're daydreams with a touch of trauma.

The temptation for the show as it continues to peak will be to harmonize Bart with those bootleg T-shirts and make him a socially aware little dude. Reformers always want to hitch a ride on a hit. It's suasion I hope the show resists. We need our uneasy idylls. They provide a recreational base for our hampered spirits. Let Cosby build character. Let Allan Bloom just keep rollin' along like Old Man River. From Huck Finn to Bart Simpson is a happy continuum. After all, Bart saved France.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now