Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowPICTURES OF LILLY

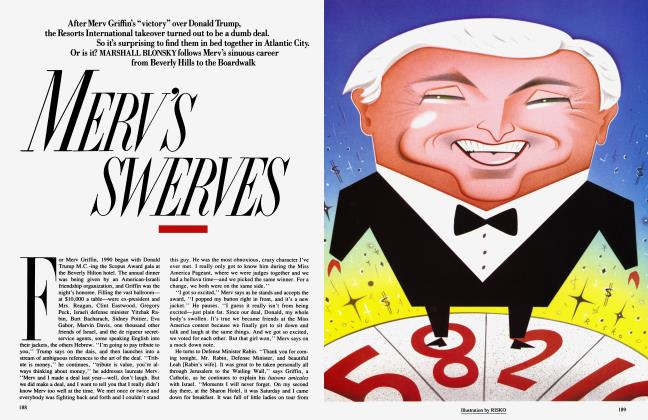

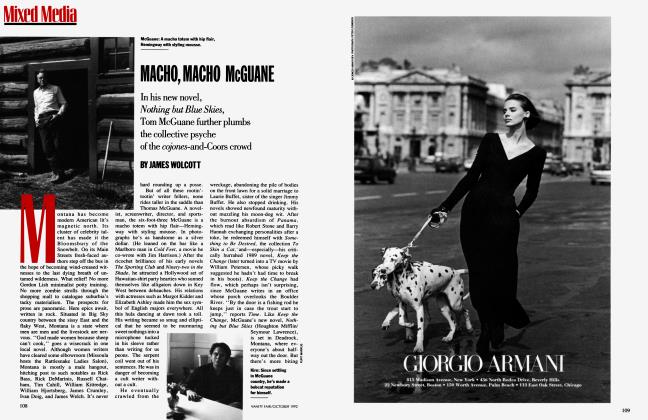

Letter from Hollywood

Why Lilly Tartikoff, the zany wife of NBC's president, has been compared to Gracie Allen, Mr. Magoo, and a pit bull

LYNN HIRSCHBERG

Hollywood, the ultimate company town, thrives on a precarious balance of information and secrecy. Power is often determined by how much you know, who knows you know it, and, most important, what you may know that you're not saying. The wives of the men who run Hollywood— and it is run almost entirely by men—learn to play by the same rules as their husbands. They aim to be politically correct and discreet.

Except one. Lilly Tartikoff, the wife of NBC network head Brandon Tartikoff, resembles a madcap heroine in one of her husband's loonier shows more than a typical Hollywood wife. Where Candy Spelling, the quintessential wife of the eighties, was prone to excess, Lilly Tartikoff is prone to a sort of pathological wackiness. Despite the fact that her husband, who took NBC from last place to first place, is widely considered to be one of the most talented and powerful men in town, Lilly Tartikoff is nei-

ther discreet nor particularly political. "Lilly is nuts," says one studio head. "I love her, we all love her, but she is completely, absolutely, totally nuts."

'Where did you come from?" was the question that Ronald Perelman, C.E.O. of Revlon, asked Lilly Tartikoff after she pushed him into a hedgerow at the Beverly Hills Hotel. "Where did we find you?" he said, picking himself up and brushing himself off. "Ronald was stunned," explains Lilly. "But he was a sport. He got back on his feet. It was just that he had never met anyone as crazy as me before."

Lilly, whose striking resemblance to Sean Young may account for the fact that at the Ghostbusters II gala in L.A. last summer James Woods took one look at her and started to run in the opposite direction, is quite cheerful about her bout with Perelman. She was pursuing him, she says, for a specific reason—to persuade him to donate $2.4 million of Revlon's money to help finance a breast-and-ovarian-cancer research program at U.C.L.A.

"I was on the Max Factor advisory

board," she recalls. ''And Revlon owns Max Factor. I figured if I could get to Ronald Perelman, I could talk him into it." So she wrote letters and made phone calls and then, six months ago, she finally met him. Perelman was pleasant, and seemed vaguely interested in her cancercenter idea, but at first he underestimated her determination. And one should never do that. ''I became obsessed with this project," she says. "Obsessed! There was no stopping me. I was no different than a pit bull." So she pressed. And when Lilly Tartikoff presses, her nerve is compelling. ''Lilly is like Mr. Magoo," says her husband. "She walks calmly through minefields while bombs are going off around her and comes out unscathed."

"Early on, I made a decision about life," explains Lilly, who was a dancer with the New York City Ballet. "I decided that until I met someone as brilliant as Balanchine, and whose buns were as tight as Baryshnikov's, there wasn't a whole lot to be impressed by."

Which brings us back to that hedge at the Beverly Hills Hotel. Apparently, Perelman was showing a touch of hesitation, and Lilly grew impatient. "We were having drinks, and I wasn't finished with him," she recalls. "I said, 'I'll walk you to your bungalow.' He said, 'Well, U.C.L.A. is the numberfive school.' I said, 'I've read some articles that say you are number five.' That's when he fell into the bush."

But Perelman's shock passed nearly instantly—with Lilly, initial surprise often turns to amusement—and he decided to donate the money, provided that she throw an annual charity ball, the first of which is on March 13, to supplement the $2.4 million. "When he finally said, 'O.K.! I'll do it! Now get out of my office!' I was so happy. I grabbed his secretary and said, 'You heard him, didn't you?' Ronald was stunned. He kept saying, 'Where did she come from?'" Lilly Tartikoff smiles.

'Lilly, Lilly, Lilly,'' says Robert C. Wright, C.E.O. of NBC, laughing. "Lilly is not.. .shy." Nearly everyone in the entertainment community has a Lilly story; they swap them like baseball cards. "She's catalytic—sparks fly when Lilly's around," says Tom Brokaw. "Although I've never seen her be malicious. She doesn't have any hidden agendas."

"She's a very free-spirited woman," says (Über-agent Michael Ovitz of Creative Artists Agency. "She says whatever she thinks in any given situation. If other people said the same thing, it might be construed as questionable. But with Lilly it's always quite charming."

"After all, Brandon is the peacock," says Lilly."They should just put Brandon's little head on those feathers."

The key to that charm is a combination of directness and a sort of Gracie Allen-ish dizziness. "Lilly doesn't change," says her husband. "She acts the same if she's standing in the schoolyard, or at Bill Cosby's house, or at an affiliate directors' meeting, or at a dinner party for the people from G.E. At times I tell her, 'Not everyone needs to know everything you're thinking the moment you are thinking it,' but that's just Lilly."

Tartikoff has never tried to censor her. "He lets me fall into traps," Lilly explains. "And he expects me to get out of them. That means I spend half my life getting into trouble and the other half trying to get out of it."

This pattern began some ten years ago, at one of the first Hollywood parties Lilly ever attended. "We went to this party in October of 1981," recalls Tartikoff. "It was right after Hill Street Blues won all the Emmys. Lilly walked up to Tony Thomopoulos, who was then head of ABC. She said, 'Your show is so terrific, and congratulations on all those Emmys.' He just stared at her. 'What show?' he said. 'What Emmys?' 'Well,' Lilly said, 'Hill Street Blues, of course.' She thought Tony was Steven Bochco, the producer of Hill Street. It was like that all night. Lilly was a steamroller leveling people's egos."

Not much has changed. Last summer, the Tartikoffs were visiting their close friends Susan Saint James and Dick Ebersol at their home in Litchfield, Connecticut. While Brandon was teaching his six-year-old godson, Charlie Ebersol, how to hit a baseball, Lilly and Susan went off to a reception that Richard Holbrooke, an investment banker at Shearson Lehman, was giving for his mother. At this party, Lilly was introduced to Henry Kissinger. "She said hello," recalls Holbrooke. "And then, ten minutes later, she came running back over to Kissinger and yelled, 'You really are Henry Kissinger!' Kissinger looked startled. 'I thought you were a celebrity look-alike!' Lilly said, and she asked him if he would come to the next party with her and just pretend to be Henry Kissinger."

"When I leave NBC," says Brandon, "my first situation comedy will have a character like Lilly. I'm planning to stay at home and take notes. Like last night at dinner, we were out with Jimmy Burrows, the producer of Cheers, and he mentioned he'd been to Cooperstown, home of the Baseball Hall of Fame. I said to Lilly, 'Do you know what Cooperstown's all about?' She said, 'Is that where all the people drank the lemonade?' I said, 'No, Lilly, that's Jonestown, and it was Kool-Aid.' " Tartikoff sighs, and laughs.

'I had no idea what I was marrying," I Lilly says. "No idea at all." She is I sitting in the living room of their Coldwater Canyon home. The room, which is dominated by a huge Roy Lichtenstein on one wall and two cherry-red outsize leather club chairs, is remarkably vivid. "When I renovated the house," Lilly recalls, "Brandon said, 'Surprise me.' I said, 'Brandon, this is not normal behavior.' But then when he saw this room for the first time he said, 'Have you lost your mind?' After all, it is an outrageous room." Lilly looks around. "Now, of course, he loves it."

Brandon Tartikoff and Lilly Samuels met eleven years ago at a tennis party in Los Angeles. Lilly, who is now thirtysix, was on a break from the New York City Ballet and was visiting her boyfriend in her native L.A. "My friend, who was giving the party, worked at Paramount," Lilly says. "He told me, 'Brandon Tartikoff is coming. He's a private kind of person.' I said, 'What was that name?' When the party started, I asked my friend, 'Where's that private person with the funny last name?' They pointed him out. I thought he was cute, and we just hit it off. I always knew we would get together. He might not have had that feeling, but I did."

At the time, there was a whiz-kid buzz about Tartikoff in Hollywood. Barely thirty, he was the protege of Fred Silverman, the man who had made ABC number one and was attempting the same miracle with NBC. Tartikoff, who grew up in New York, attended Yale and began his TV career in Chicago. While he was in Chicago, he was diagnosed as having Hodgkin's disease, one of the most treatable forms of cancer. He underwent chemotherapy, and the disease is now in permanent remission.

When Lilly and Brandon met in 1979, he was head of West Coast television for NBC, which was in dead-last place. "He liked that I knew nothing about television," Lilly recalls. "He even liked that I couldn't figure out what it was that he did." Lilly, who grew up in Los Angeles—her father manufactures accessories—returned to New York. At twenty-six, she'd been with NYCB eight years, and as her relationship with Brandon heated up, she became less enthralled with the difficult world of the ballet. "The other girls in my group went on to be principal dancers," she says. "I went on to get married and run NBC."

Before leaving the company, Lilly "wanted to show Brandon my world." In 1980 they met in Paris for the end of the European tour. "After Paris," Lilly says, "we went to the South of France. It was so beautiful, but Brandon was getting antsier and antsier. At the time I thought, Oh, he's not comfortable traveling. I should have known that he would always be antsy. One day we passed a newsstand, and the headline on the Herald Tribune was SHOGUN 57 SHARE—NBC REJOICING. This was NBC's first hit in years. Brandon looked at me and said, 'Look at this.' I looked. 'NBC is rejoicing, and I'm here.' "

Despite Shogun's success, NBC was in third place. In 1980, Fred Silverman Lnamed Tartikoff, who was then thirtyone, head of programming for the network. In 1981, after a wildly disastrous season, Silverman was fired, and NBC hired Grant Tinker as C.E.O. "It was almost embarrassing to tell people my boyfriend was the president of NBC,'' says Lilly. "NBC was a mess."

By then, Lilly had quit NYCB and moved in with Tartikoff. After overcoming culture shock—"The breasts!" she exclaims. "In L.A., everyone had bazooms!"—Lilly settled into her new life, and she and Brandon married in 1982. Their daughter, Calla, was bom later the same year. Things at NBC also changed. In 1983 the network won a record number of Emmys for shows like Hill Street Blues. After six consecutive losing seasons, it also had its first number-one hit with The A-Team. And then one night Lilly and Brandon saw Bill Cosby talking about parenthood on The Tonight Show. "Brandon watched for a while," Lilly recalls. "And then he said, 'This is the show right here.' Bill Cosby changed Brandon's life."

The Cosby Show, along with programs like Cheers and Miami Vice and The Golden Girls and Family Ties, made NBC number one by 1985. In 1986, General Electric acquired NBC, and Grant Tinker quit the network to return to independent producing. Robert C. Wright was named C.E.O., and Tartikoff stayed on. NBC has been number one ever since.

"I tell her, 'Not everyone needs to know everything you're thinking the moment you are thinking it,' but that's just Lilly."

"When Brandon gets up in the morning," Lilly says, "he doesn't say, 'Good morning, Lilly.' The first thing he does is look at the squares near his bed." The squares she is talking about are a monthly calendar of prime-time programs for all three networks. "Those squares are with him at all times—he's like the priest who carries the Bible— and first thing every morning he maneuvers shows, moves shows around, and then calls up and gets the overnight ratings. That's his ritual. Nothing has changed in ten years."

Lilly laughs. "I didn't realize what I was getting myself into. I mean, I deal with a man who's a maniac. He can't stop working. Brandon is so focused and so intense about his work that that is literally all he does. He's a great daddy and a wonderful husband, but aside from that, he doesn't do the bills or buy the houses or anything. I mean, we'd be in the same little house we started out in, with the same old car, if it was up to Brandon. Most people care about that, but not him. It's not that he's so trusting; he just really doesn't care. I mean, I buy his shoes. Salesmen ask me, 'Does he have a high thrust?' I say, 'Nine and a half D—he'll make 'em fit. He's not fussy.' He could have an Armani suit on and just wear the worst shoes. Or the wrong socks. We can't get into fancy socks or suede loafers—we stick to basics. There are no nuances in this wardrobe."

Lilly throws up her hands. "They can't pay me enough to do the things I have to do," she says, cracking herself up. "I'm an abused wife."

I t's a typical Saturday morning at the Tartikoffs'. Calla has a pal over and they're watching cartoons on TV, a personal trainer is here to work Lilly and Brandon out, and there is some discussion about going to see She-Devil this afternoon. "I promised myself that after last year I wasn't going to make a big deal out of Brandon's birthday," Lilly says. "And so I almost forgot that today is Brandon's forty-first birthday."

Last year, Lilly threw a fortieth-birthday party for her husband at Dodger Stadium. "For Brandon, TV comes second to baseball," says Lilly. "Baseball is Brandon's love beyond love." So last January 15, Jay Leno met Tartikoff at his house with a film crew, put him on a helicopter, and flew him into Dodger Stadium, where six hundred friends and relatives were waiting. "I was nuts. I was like Hitler," recalls Lilly. "We had the U.S.C. marching band and cheerleaders, and we had Dodger Dogs and cake and party hats. We put a film together—Brandon Tartikoff, This Is Your Life—that we showed on the Diamond Vision screen. It was a great party."

Today, a year later, things are much quieter. Only one gift so far: Mike Ovitz has sent over a Casio watch. "The only trouble is," Tartikoff says, "that I don't wear a watch. I wore one for two years, when they made me chairman of programming in 1987. But when I put on Yesterday, Today & Tomorrow last year, time stopped. I took off the watch."

Tartikoff heads off to the shower, and Lilly tends to Calla, who is dying to go to the movies. "There's a wonderful yin and yang to Brandon's and Lilly's personalities," says Tom Brokaw. "Brandon's humor is the essence of subtlety. For all of his power, Brandon is lowkey. Lilly is always percolating. She's Brandon's greatest cheerleader." "She's like a tiger with her cub," says Wright. "Brandon can be mild, because he knows she's fighting the dragons on one side of the lot."

In 1986, when G.E. took control of NBC, Lilly became particularly protective. After buying the company, no one from General Electric called Tartikoff to ask him to stay, or even just to say hello. "Months went by, and they didn't call," recalls Tartikoff. "I kept saying, 'I can't believe they haven't called me.' " Meanwhile, he was receiving other offers—Columbia Pictures, for instance, was wooing him—and finally Lilly took action. She called Dick Ebersol, who called his friend producer Don Ohlmeyer, who plays golf with Jack Welch, C.E.O. of G.E. "Do you realize you've got a very unhappy guy there, and he might leave?" Ohlmeyer said to Welch. Welch then called and asked Brandon to dinner, and the two hit it off perfectly. "And that's why I still have peacocks on my beach towels," says Lilly Tartikoff.

Lilly is lost. She is driving to the biannual NBC press conference at the Registry Hotel near Universal Studios, and she's confused about her route. "I am constantly lost," she says, finding her way. "And so is Brandon. He spends 90 percent of his life running NBC and the other 10 percent being lost. He finally got a car phone just so he could call and ask for directions."

Pulling up to the hotel, Lilly, who is wearing a smart gray suit with brown velvet lapels and carrying a Chanel bag, is met by an NBC page, who escorts her into the hotel's main ballroom. She takes a seat, along with some 125 members of the nation's press, and waits for Tartikoff to appear. "These press conferences are like boxing matches," Brandon has said earlier. "They're constantly trying to open a wound."

Actually, the questions today are fairly mild. Tartikoff announces the return of Dark Shadows and fields inquiries about Jeff Sagansky, his former number two at NBC, who is now head of CBS programming. He details his counterprogramming strategy for the upcoming baseball season—he'll run three Danielle Steel movies opposite the play-offs and World Series—and he sings the praises of a new show entitled Nasty Boys. After ninety minutes, Lilly raises her hand to ask a question. Tartikoff, who doesn't see her, calls on someone else and brings the press conference to a close. "Too bad,'' Lilly says. "Here's what I was going to ask: Warren Littlefield [Tartikoff's current number two] and I want to know how much longer you're going to be at NBC.''

It's a good question. This is Tartikoff s tenth year as head of the network. He signed a multiyear contract a couple of years ago, but it is not likely that he'll stay at NBC longer than two more years. No one has ever held the job this long, and it is a draining position. "Brandon may leave six months from now," says Lilly wistfully. "I'm going to be sad when he leaves. I haven't known Brandon not at NBC."

Tartikoff has many other options. He could, potentially, run a movie studio, although TV is in his blood. In all likelihood, he will start an independent production company and create shows for NBC. "Brandon is a player," says one studio head. "He's brilliant at what he does. I think he'll miss the action when he leaves NBC. Secretly, I don't think he'll ever leave."

Lilly hints at this possibility as well. "Brandon's used to working on such a big scale," she says. "There were years I wanted him to leave NBC, but now that it's getting to the winding-down time, I live in fear. After all, Brandon is the peacock. They should just put Brandon's little head on those feathers."

Tartikoff has been preparing Lilly for his departure for years. "Brandon always says if we leave NBC on any July first, by July second nobody's going to talk to me. 'Lilly,' he says, 'none of these people are going to deal with you when I leave NBC.' "

Lilly shrugs off such talk. "When we leave NBC," she says after the press conference, "we walk out of town." She pauses. "I say that, but I don't really believe it. I don't know what we'll do." Lilly brightens. "Or I should say, don't know yet. Somehow I'll think of something."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now