Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowKING FflHD'S BIG GAMBLE

Will the intensely pro-American monarch— and the House of Saud—survive the fallout of the Gulf War?

PETER THEROUX

Letter from Riyadh

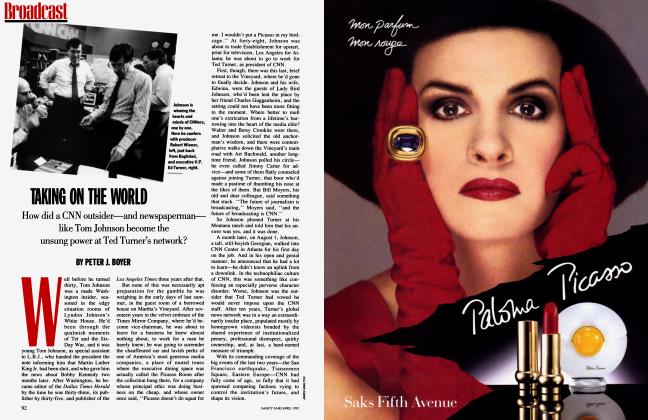

It was in the peaceful green city of Taif, nestled in the lush mountains of the Asir, that King Fahd ibn Abdul Aziz al-Saud's long and brilliant career at back-room royal intrigue and petrodollar-fueled diplomacy came to an end. Nothing had prepared him for the ugly military realities of an aggrieved and ruthless Arab neighbor. Brokering deals among local princes, a close alliance with the seemingly omnipotent and omnipresent United States of America, and the deft deployment of cash have always been Fahd's preferred means of solving problems.

And so, only hours before a hard-eyed Saddam Hussein rolled his tanks in to dismantle Kuwait, the Saudi Arabian ruler was still playing host to Iraqi and Kuwaiti diplomats at TaiFs towering, brushed-steel Conference Palace, built in 1980 to fete Islamic unity. The tapestried walls and inch-thick Persian carpets, which had muffled unnumbered political negotiations, became the setting for unprecedented ugliness.

"The Kuwaitis had been instructed to yield to Saddam's demands," says Douglas Graham, author of Saudi Arabia Unveiled. "The Saudis were sure they had helped defuse a fratricidal conflict between Arabs." Instead, Kuwait was about to be devoured, and rather than jetting home from Taif Airport the Kuwaiti officials were soon joined by nearly their whole government. Almost as significantly, for the Saudis, the era of checkbook diplomacy was over.

Saudi Arabia's king was bom to be prince of Monaco. He loves the prerogatives of his job, and seems in almost every way to be wrong for it. Obese and erratic at sixty-nine, Fahd has led a sybaritic life only recently abandoned as a favor to his fragile heart. His youth is still the stuff of legend in Saudi Arabia: how he lost millions, even tens of millions, in London casinos; how, incensed at English gaming laws, he rented blackjack and roulette tables, chips and dealers, and installed them in his hotel suite so he could play all night. His conquests among the priciest beauties of Beirut and Monte Carlo are retold with gusto by both friend and foe.

His family, however, felt his conduct did not become a Saudi prince. In 1953, Fahd was summoned home for a serious scolding, and until 1982, when he ascended the throne, his resume was a flawless string of jobs well done: he served as an able education minister, minister of the interior, and power behind the throne during the seven-year reign of his older brother King Khalid, a kindly old man widely seen as something of a bumpkin. In the 1960s, against conservative opposition, Fahd promoted education for girls, and his pro-American opinions have given him the aura of a smiling modernizer in a family of scowling obscurantists. This cost him the trust of the Muslim ulema and mashayikh, the dour clerics a Saudi monarch must routinely welcome in audience every Tuesday afternoon.

After he became king, Fahd's Western sympathies continued to cause trouble with the eleven immensely powerful religious institutions whose support is essential to his rule. They were angered, for instance, by his donations to the Nicaraguan contras—Muslim money, they felt, should not go for C.I.A. adventures. To placate them, this former liberal education minister banned the teaching of music in schools. "When shepherds become friends, the sheep are lost" is an old Arab proverb, and in the bitcheries of prince versus priest, the people get whipsawed.

Saudi kings have, of course, a long history of overruling the religious establishment: the kingdom's founder, Abdul Aziz, forced the benighted sheikhs of his time to accept telephones and radio, and both Khalid and King Faisal before him successfully pushed for modernization. But they had unassailable credentials for pietism; Fahd, with his checkered past, has to tread carefully around the fundamentalist clergy. "They don't trust him, and they can smell the fear on him," shrugs Graham.

With his marriage in the early 1980s to Johara al-Ibrahim, the daughter of a provincial governor and his only wife (of what is said to be a trio) to use the title of queen, Fahd put most of his extracurricular lust into mortar and marble. Early in his reign, he began building al-Yamamah, a huge complex atop an escarpment looming over the palace-choked precincts of southwest Riyadh, and not only does this dwarf his homes in Geneva, Marbella, and the French Riviera, its scale utterly overwhelms Riyadh's other palaces.

Saudi kings leave too many widows for their palaces to be passed on to their successors, so until Fahd built al-Yamamah the closest thing Riyadh had to the White House was al-Maazar, a mediumscale administrative palace completed in the early 1960s. Al-Yamamah, which visitors tend to describe in terms of airline terminals and football fields, is a gigantic assemblage of marble, granite, rosewood, and gold—really a small city of harems, servants' quarters, garages, and kitchens. At one comer, a white mosque—which on closer inspection reveals zigzags of exquisitely light pastels—is open to the public. The official line is that al-Yamamah will be Saudi Arabia's permanent seat of government; whether a widowed Johara or any of Fahd's notoriously spoiled children would relinquish it is another question.

Fahd himself is too high, wide, and handsome to like Riyadh much. The insularity and snarling religiosity of the capital lead him to spend most of his time away from al-Yamamah, at his seaside residences in Jidda and Rabigh, a few miles up the coral-encrusted coast. It is no fluke that he has the best yacht (the Abdul Aziz, after his youngest son), the best plane (a $150 million 747 with an English-manor decor, including a fountain), and the most palaces abroad of any Saudi monarch.

Like the late Shah of Iran, Fahd has a most unkingly eagerness to be liked by big foreign powers, reserving his warmest affection for Americans and Europeans. Unsurprisingly, the wealth and vulnerability of the kingdom have tempted Fahd to go too far. He noisily presented the 1981 purchase of AWACS planes from the U.S. as a massive victory against the pro-Israel lobbies in Washington, but many Saudis did not see the triumph in being allowed to pay $8.5 billion for five planes and some refueling aircraft. He was too quick to call for American help to sweep for mines in the Red Sea in 1984—there turned out to be no more mines. Worst of all, in a part of the world where even the most pauperish recipients of American aid dole out their gratitude stingily, Fahd let the Americans know what he thought of them.

Saudi and American diplomats still hate to talk about Fahd's fawning outburst in the summer of 1984, when Charles Z. Wick, Ronald Reagan's close friend and then director of the U.S. Information Agency, was visiting Riyadh.

''Before you leave I want to ask you for a favor," the king told Wick.

Wick may well have viewed the request with trepidation: the Arab world was boiling with rage and humiliation over America's apparent complicity in the Israeli invasion of Lebanon, and the Saudi press had been a vigorous mouthpiece for Arab opinion. But Wick's royal em counter at the Maazar palace had overflowed with good feeling, and lasted nearly triple its scheduled fifteen minutes, so he delightedly granted the favor in advance.

"On November 6," said a smiling Fahd, with a gesture toward the U.S. ambassador, seated beside Wick, "I want to get in my car and go up to the American Embassy and cast a vote for my friend Ronald Reagan! Now, I know I'm not a citizen—but do you think you can arrange it?"

The audience quickly broke up amid cordial laughter and enthusiastic handshakes, and Wick was sped to King Khalid International Airport in high spirits. For the Saudi and American staffers present, however, the sparkle of the meeting was fogged in bewilderment at Fahd's incredible behavior. With American-made cluster bombs blowing Beirut to pieces, and anti-American sentiment off the charts in nearly every Arab country, couldn't Fahd offer one friendly suggestion to put Reagan in the picture, not even just for the record? Was he aware of the signal he was sending?

The "Reagan Plan" for peace in Lebanon was dying, and Fahd was the only Arab with clout enough to help Reagan out, if he dared. But Fahd, who prefers the fuzzy sentimentality and show biz of Arab unity to the actual pain and unrest of the Arabs, was the wrong man for the job. The rich Persian Gulf sheikhs had always looked down on the squalof and violence of their poor cousins, which in any case didn't threaten their regimes—yet.

Part of the trouble is that the royal family in 1991 is very different from the A1 Saud they started out to be. What makes a prince of a Saudi is having Abdul Aziz ibn Abdul Rahman alSaud as an ancestor. Between 1912 and 1927 this devout, hulking desert warrior and his fanatical soldiers conquered and united the territories of Nejd, in the central region of the Arabian Peninsula; Hejaz, with the cities of Mecca, Medina, and Jidda, on the Red Sea; the green hills of the Asir, near Yemen; and the Ottoman province of al-Hasa, beneath which billions of barrels of crude oil slumbered.

Wary of the imperialistic British, Abdul Aziz gave the country's oil concession to Standard Oil of California in 1933, and started building his dynasty. He co-opted hostile or competing tribes and clans through endless marriages, with the added benefit that the resulting hordes of children provided him with decades' worth of successors. For the Saudi succession, like a knight's move in chess, went from Abdul Aziz, on his death in 1953, down to his son Saud and then horizontally to Saud's brothers: Faisal, Khalid, and now Fahd.

It was Saud who did the most to give the West—and poorer Arabs—the pinkCadillac icon of oil Arabs. "My father was a nice man, not a corrupt man. They hated him because he loved people, because he gave away money—even threw gold coins from his open car!" sighs Prince Muatasam ibn Saud, whose Eritrean mother still lives with at least twenty other of King Saud's widows in an elegant populuxe-era compound in Riyadh. "They" are presumably his uncles, especially Faisal, who deposed Saud when the affable but syphilitic and alcoholic king began bankrupting the country in the late 1950s.

Faisal is best remembered in the West for his hawklike profile and punishing but unsuccessful 1973 oil embargo against the U.S., Britain, and Holland, but at home his memory is equally associated with his abolition of chattel slavery in 1962, his foiling a military coup in 1969, and his assassination by a nephew in 1975. His disdain for superpowers is fondly recalled. When Henry Kissinger's urgent shuttle diplomacy took him to Riyadh from Cairo and Damascus in 1974, and King Faisal was informed that the American had arrived and had demanded an immediate meeting, he sneered, ("Soak him"). Kissinger was kept waiting a full day and a half. Faisal's better-treated visitors always spoke of his strict monogamy (to a Turkish woman named Iffat) and his usual parting words of wisdom: "Never forget Karl Marx was a Jew."

Faisal was followed by Khalid, who reputedly achieved the throne through a deadlock between Fahd and another brother, Abdullah, over who had been bom earlier. Birth records were not kept in 1920s Arabia, and such arguments, according to Saudi writer Abdelrahman Munif, were often settled by richly bribed midwives and nannies. Fahd was named Khalid's crown prince on the condition that Abdullah would be next in line.

After Khalid's death in 1982, Fahd reluctantly repaired to the capital, his arrival heralded by a stupendous fireworks show—the first ever seen in Riyadh. "Modem, splashy in a very un-Saudi way, and, well, happy—also in a very un-Saudi way" was Hamdan al-Ghamdi's description of the event, as he winced at the thunderous blasts that echoed across the city, whose beigeness was illuminated by the explosions of light. This was a long way from the tough, dour rulers who used to have their citizens beaten for laughing or singing in public.

In modem times, an outward show of austerity has masked considerable private liberties. For decades Saudi money has been spent to import whole night spots and brothels, only to ship them out the morning after. Playgrounds like Iran and Lebanon blew up, but Europe and America took their place, and the Saudis, once gawking arrivistes at debauchery, have learned the game.

A certain nephew of Fahd's comes to mind (the size of the family defeats the use of pseudonyms), one who lived well if placidly in Riyadh, enduring the long prayers and dinners with his mother, and wearing the Arab uniform of prince and commoner. Every couple of months this prince, a new man in impeccable Armani and a glossy black pompadour, set out for New York, where he checked into the Pierre and made a beeline for Greenwich Village pleasure domes like the Toilet and the Mineshaft. A blissful night of bruising group sex and urine baths followed by a shower, breakfast, and a nap back at the hotel fortified him for a session with his money managers. After a week of banking days and "B&D" nights (he yelped with laughter at an American who did not know the insider's term for bondage and discipline), he headed back to Riyadh.

Such a prince could, on the surface, never have been imagined by his grandfather Abdul Aziz, but he has much in common with him. Unlike Fahd, he sees through Saudi and American facades with unbiased ferocity. He would never have joked about yearning to vote for Ronald Reagan—if he had the yearning, he would certainly have kept it to himself.

Today the A1 Saud resemble a populous, epicurean social caste more than a royal family, let alone an Islamic royal family. No one knows exactly how many there are, possibly not even the secret government department, headed by an anonymous senior prince, whose sole job is to gather intelligence on the royal family itself, though guesstimates range from 4,000 to 10,000 princes and princesses.

I got an accidental insight into the growth curve of the A1 Saud on a visit to the King Faisal Specialist Hospital, a Saudis-only facility whose maternity

There's a secret government office, run by an anonymous prince, whose sole job is to gather intelligence on the royal family itself. ward and substance-abuse clinic were especially advanced. Standing at the guardhouse to locate the name of the invalid I was visiting, I was handed the fat computer printout of patients. Here was a revelation: two fanfolds of "Baby Boy al-Saud, Baby Boy al-Saud, Baby Girl al-Saud, Baby Boy al-Saud." Each would cost the Saudi treasury a stipend of between $500 and $8,000 per month for life.

As the varying sums suggest, not all A1 Saud are created equal. King Fahd has six brothers who look especially alike, and who virtually run the country along with him. They are known as the Sudairi Seven (after their late mother, Hassa bint Ahmed al-Sudairi, Abdul Aziz's favorite). Sultan, the eldest after Fahd, is minister of defense; Abdul Rahman, deputy minister of defense; Nayef, minister of the interior; Ahmed, deputy minister of the interior; and Salman, governor of Riyadh. Only one, Turki, is sporadically in and out of disgrace and government employ. Turki also has to lug around the social millstone of his in-laws, the Mohammed al-Fassis, the statuary-painting, chartreuse-chateaubuying parvenus of Beverly Hills and Miami.

The only man outside the Sudairi Seven with significant power is Crown Prince Abdullah, Abdul Aziz's only son by a conquered widow of the central-Arabian Shammar tribe. Abdullah's connections are Arab rather than American or European. He married into the inner circle of Syrian president Hafez al-Assad, and is something of a one-man Syrian lobby. Abdullah commands the 56,000-man National Guard, Saudi Arabia's "second army," used for internal security and counterterrorism during the deployment of the other armed forces in the war with Iraq.

Unlike King Fahd, the crown prince spends most of his time in Riyadh. His National Guard headquarters looms over the suburb of Khurais, and when Abdullah is not hunting in the desert or twisting arms in Damascus or Amman, he is there. Despite their differences, the half-brothers have their own way of working together. Abdullah's wellknown distrust of dependence on the United States is exploited by Fahd, and the crown prince has played "bad cop" with visiting congressmen, scolding them on the Palestinian issue after they'd been coddled by Fahd.

The relationship between the masters of Saudi Arabia's two armies has had its dicey moments. It was Abdullah's opposition to Fahd's pro-American ideas that sent then crown prince Fahd into a fourmonth voluntary exile in 1979, when the family was debating whether to seek open American help in the wake of the Iranian revolution. And in 1985, Fahd and Abdullah had a huge row over the question of aid to Lebanon. Fahd, who supported the ruling pro-Israeli Phalange Party, wanted to send $150 million in funds; Abdullah, on Syrian principles and his own, wanted the Phalange to earn the aid by making concessions to Lebanese Muslims.

Much to the horror of the U.S. Embassy, which wanted the money paid out, the disagreement grew into a feud, and there were rumors of Fahd flouncing off to Marbella, or Abdullah retreating to the desert to sulk. Eventually they compromised: Saudi royals keep good brakes on their feuds, realizing that at the end of the day their interests—preserving the dynasty, united and in power—are identical.

In 1983, after a period of popular unrest and reports of an attempted coup, the A1 Fahd, as the Sudairi Seven are also known, closed their hands over even more levers of power, appointing their sons to key posts.

Fahd has about a dozen children, some rising stars and some disappointments. His daughters have "the unmerciful bad luck," as one of their friends puts it, of being overweight and much divorced in a country where enviable marriages and drop-dead chic are the air that wealthy women breathe. And scandal has prevented his oldest son, Faisal, from holding any office more ambitious than director of the General Presidency of Youth Welfare. Faisal, who was generally believed to have had a drug-abuse problem, was said to have shot his male lover, a National Guardsman from the tribe of Shammar. The guardsman's family refused diya, blood money, in place of the killer's head, so Fahd dispatched Faisal to Los Angeles until the storm blew over. To show that he was not in disgrace, the Saudi papers reported him to be busy helping plan the 1984 Olympiad. But the avenging family stuck to its guns and went to Crown Prince Abdullah, pressing its claim to Islamic satisfaction.

Though Abdullah is a Shammar on his mother's side, even he could not demand that the king have his oldest son tried for murder. The family, which reportedly turned down colossal amounts of hush money, had to be seriously browbeaten before giving up the vendetta.

If Faisal has been a disappointment, sixteen-year-old Abdul Aziz ibn Fahd, the king's youngest son, is so favored by his father that he owns one of Riyadh's most elegant palaces, and routinely donates plots of land and millions of dollars to local schools, the Afghan resistance, and Islamic charities. Throughout his boyhood he accompanied his father everywhere, even to high-level meetings (although the sultan of Oman once ordered him out of a summit conference in Muscat).

The trouble with the resurgence of the A1 Fahd in all its generations was not the intimidation of other branches of the royal family. It was that it sounded a death knell for the age of the talented commoner, which had seen the rise of such figures as Oil Minister Ahmed Zaki Yamani, who was then judged to be too much of a media star abroad.

fahd has to tread carefully with the fundamentalist clergy. "They don't trust him, and they can smell the fear on him."

As the hometown of the A1 Saud, Riyadh was the logical choice for the royal capital, and its central location served to lessen and balance the influence of the rich coastal cities—Jidda, on the Red Sea, and mostly-Shiite Qatif, on the Persian Gulf. Today, it has an American profile—a very Californian profile, with its polished skyscrapers rising from the desert floor. The vista is monochromatic, but an aerial view reveals that the austere, dusty, ten-foot walls lining all the residential streets hide a brilliant jigsaw of red tiled roofs, emerald-green lawns, and turquoise swimming pools.

Riyadh has always exemplified Saudi Arabia in its scale, its bottomless insecurity, its almost science-fictional grandeur, and its equally impressive resistance to change. But this is where change will come first. It is where Saudi women decided to stage a protest against the ban on women driving, because in any less top-drawer province the protest might have set off fears of wider political rebellion.

The current danger for the Saudi government stems from the fact that it has always cultivated among its people a certain hostility toward the United States, disdainful rather than violent, intended to divert criticism away from itself. For years Saudis did not mind the sight of the gigantic U.S. Military Training Mission in the middle of Riyadh, or the hundreds of Vietnam veterans training the National Guard in Khurais, because they read scathing editorials about "Zionist-directed" American politics in Al-Jazira and were taught in school about the pitiable decadence of American society. Their assumption was that their government's eyes were open, that Saudi Arabia was taking the good from America and leaving the bad, or even that the kingdom was trying to chide and civilize the United States.

It was inevitable that events would cause this cynical policy to backfire. ''America is only here protecting Israel" was a frequent Saudi grumble heard after the massive allied deployment last year. If no one could claim that the A1 Saud were "outted" by the war, Saudis could no longer ignore the bald fact that their rulers were on the American team, and only their king could explain the contradiction, or produce the benefits that might justify it.

So delicate was the Saudi plight that the government, incongruously, did not report news of Iraq's Scud attacks on Tel Aviv. All attention had to be concentrated on the American-led liberation of Kuwait and elimination of the military threat to Saudi Arabia—and even that may not prove to have been adequate justification for the infidel presence. "This will heighten the instability," says leading oil expert G. Henry Schuler. "Our whole approach to oil over the years has been that the major threat is external aggression, and that the answer is military deployment. But the real threat is internal upheaval."

The main voice of Saudi opposition is the Organization of the Islamic Revolution in the Arabian Peninsula (OIRAP), a predominantly Shiite group whose monthly magazine, Al Thawra Al Islamiya ("The Islamic Revolution"), is a surprisingly witty and well-informed read, strong on news of recent arrests of Saudi dissidents and the financial improprieties of the Al Saud. Undoubtedly funded in part by Iran, the outfit illustrates the importance of Islamic values as the key link between Saudi dissidents of all stripes. The Saudi socialist movement has long since merged with OIRAP, and the underground Saudi Arabian Communist Party was last heard from in 1986, at the rostrum of the Lebanese Communist Conference, where its representative presented a paper on "Contemporary Religious Movements—How to Work with Them."

When the battlefield smoke clears, the fundamentalist clergy will undoubtedly turn on the Saudi government for allowing infidels to defend—and, they'll surely allege, occupy—the holy land. For the moment, though, the future of the royal Saudi government is hanging not on Islamic fundamentalism, socialist sympathies, or even such things as whether or not it offers all its citizens the right to drive, or to vote. As Fahd and his brothers well know, the longevity of their dynasty will be decided by the results of the war.

Will Riyadh be able to blame anyone but itself if there is fallout from the Gulf War? "Put yourself in the place of the Saudi Establishment on August 2," says Harvard's Saudi expert, Nadav Safran, who goes on to tick off the worries of "the Custodian of the Two Holy Mosques" and his family: that the international community would not react strongly enough; that Saddam might even find readiness to talk it out on the part of the United States; that he might move on the nearby Eastern Province of Saudi Arabia and occupy its oil facilities, and perhaps try to knock out the Saudi monarchy. Here come the Americans, saying, 'If you are ready to resist that, then we will come in with everything.' So, this is very tempting."

Washington opinion leans heavily toward the theory that the Al Saud wanted the war, and one even hears that it was a "setup." Everyone names the same name: Prince Bandar ibn Sultan, the powerful and high-profile young Saudi ambassador to the U.S. Bandar, an American-trained fighter pilot, is much closer to King Fahd than to his father, Prince Sultan, and "seeks to be the Saudi equivalent of a national-security adviser," according to a Washington insider who has followed his career minutely.

Bandar's birth was as humble as an Al Saud's could be: to one of his father's Sudanese concubines. He is said to have been given "top status" only in the last decade, at Fahd's urging. Educated at the British Royal Air Force College at Cranwell, the prince can fly the best American hardware and is one of Washington's busiest lobbyists. Bandar has negotiated with the P.L.O., renewed the kingdom's relationship with the U.S.S.R., and made the Saudi Embassy one of Washington's highest-profile missions, even moving it to splendid new premises near the Watergate.

"Prince Bandar is close to Bush, and he goes over to the Pentagon for jet-jock talk with his friends."

He is the darling not only of Fahd— whom "he plays like a well-tuned violin"—but of the White House and the Pentagon. "Bandar is the one who went to Moscow... to see that the Russians stayed in line over the Gulf situation. He went to Beijing. He's close to Bush and was his host when Bush visited Saudi Arabia as vice president. He's close to everyone in [Washington], especially at the Pentagon—he goes over there for jet-jock talk with his friends."

Certainly he was instrumental in delivering the U.S. armed forces when the Persian Gulf oil states were threatened by Saddam Hussein. "Bandar is the key," insists one observer. Mark Bruzonsky, who heads the leftish Jewish Committee on the Middle East, has characterized the allied deployment as "an American war, not a Saudi war," and suggests that, "right or wrong, Bandar sees this as.. .in his country's national interests," leaving it to his listener to infer where Bandar's true interests lie. Others are more blunt, swearing that Bandar has made no secret of his intention to be king of Saudi Arabia.

On the face of it, this seems preposterous. In practice, succession is limited to the sons of King Abdul Aziz, and dozens of them are still living. No one in Saudi Arabia publicly asks what happens when they are gone; logically, one might guess that the throne would go to the oldest living son of Abdul Aziz's oldest son, Saud. Unfortunately, many of the brood were discredited along with the father: they have a reputation for drugs and shoplifting, no more than one or two hold important government posts, and none, by Saudi standards, are very rich. By contrast, both Faisal and Khalid have powerful and ambitious sons.

Bandar is not even the son of a king, but, as one Washingtonian notes, "he knows that the U.S. would like to see a young, pro-Western face in Riyadh. He wants to be king, and he knows it will not happen unless he's America's man. And he is clearly Washington's favorite." Still, it would mean leapfrogging literally hundreds of other potential claimants to the throne. Bandar may have the legs for it, but will the throne still be there?

More and more Saudis wonder not who will be the next king but who will be the last one. Safran has given deep thought to what the future holds for the Al Saud, and when the topic comes up his speech becomes very slow and deliberate indeed. At the most, he sees them getting "an extended lease on life" following an allied victory, possibly giving the dynasty more time than it might otherwise have had. "Without the war, well, the hourglass is filling up for them. Monarchies do not survive modernization.

"And if the worst happens, ' ' continues Safran with no trace of sadness, "and the monarchy falls in five months or five years from now, that, in the circumstances of the end of the war, would not cost the United States much sleep."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now