Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

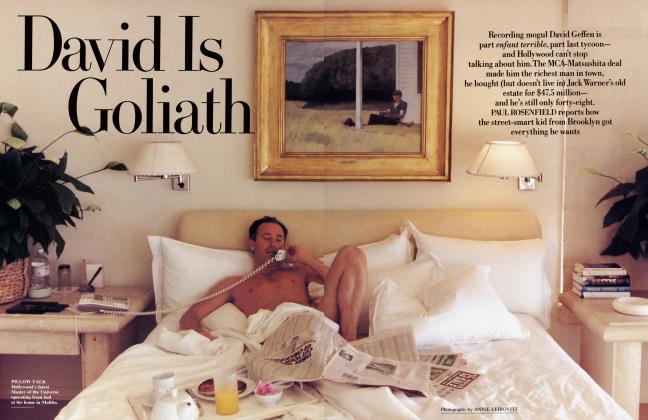

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowTHE WHOLE LINDSAY-HOGG

Movies

The many lives of the eclectic director of the Beatles, Brideshead, and a hot new movie, The Object of Beauty

BEN BRANTLEY

It seems appropriate that the two people who probably know the director Michael Lindsay-Hogg best—which may not be very well at all—offer maddeningly contradictory portraits of him. His girlfriend of nine years, the wild and worldly London socialite Nona Summers, with whom he spent last Christmas Eve, describes him as "a very masculine man" with ''a very feminine mind." The actress he lived with through most of the seventies, Jean Marsh, of Upstairs, Downstairs fame, with whom Lindsay-Hogg spent the following Christmas Day and whom he still speaks of as ''my best friend," says his sensibility is the opposite of a woman's: ''The thing about women is they want security and regularity, and Michael does not want security and regularity and cannot understand why women try to pin him down." Marsh sees him as a relatively contented nomad; Summers thinks that deep down he longs desperately for roots. She also believes he's consumed by guilt, while Marsh insists, ''You can't make him feel guilty." Ask either woman if he resembles Jake, the high-living, selfcentered protagonist of The Object of Beauty, the upcoming film written and directed by Lindsay-Hogg: Summers will answer, ''Totally." Marsh will say, ''Not at all."

Don't expect precise clarification from Lindsay-Hogg himself. ''You don't really know what you are," he says, drawing lightly on one of his trademark cigars in the sublet London town house he has temporarily made his home. He speaks in a detached-sounding, American-accented voice—dotted with the occasional British pronunciation—that curls wryly at the edges. ''You just are a collection of thoughts and desires and impulses and opinions and fears and lusts and all those things like that. I think it's very chaotic, probably, what's in people's brains.

. . .It's a very odd thing, a human being, you know."

''Odd" is one of Lindsay-Hogg's favorite adjectives, a word he savors with an epicurean relish; it also crops up frequently in other people's descriptions of him. Though he has never been—perhaps to his detriment—a self-publicizer, he is nonetheless a slightly mythic figure in show-business circles, known for his gentle solicitude with actors and spectacularly ungentle flare-ups with those who cross them; his penchants for dandyish dress and dining alone in expensive restaurants; and his unlikely reputation as a soft-spoken Don Juan, whose ''serial" (his word) romances have reportedly included Gloria Vanderbilt and Mary Tyler Moore, whom he directed on Broadway in Whose Life Is It, Anyway? He is also trailed doggedly by the rumor that he is the son of Orson Welles, whom he resembles physically and with whom his mother, the celebrated Irish-born actress Geraldine Fitzgerald, had worked during Welles's Mercury Theatre days. "Ho, ho, ho—that one," says Lindsay-Hogg when I bring up the subject. "Well, my mother, who is the only one who'd know, says I'm not. So I have nothing to add to what my mother says." His real father, he continues, is Fitzgerald's first husband, Sir Edward Lindsay-Hogg, an Irish gentleman jockey and writer, who now lives on Ibiza.

The rumor has probably been further fueled by the Wellesian precocity and versatility evident in Lindsay-Hogg's career. Certainly it represents, as one Hollywood producer puts it, "one of the oddest resumes in town.'' Since he directed his first play, at twenty-one—at a summer repertory company in upstate New York—he has worked variously in rock (as the director of the swinging British revue series Ready, Steady, Go! in the mid-sixties, and as a pioneer, in pre-MTV days, in music videos for the Beatles and the Rolling Stones); television drama (Brideshead Revisited and Tom Stoppard's Professional Foul in England, and Athol Fugard's Master Harold and the Boys for American cable); and theater (Whose Life Is It, Anyway? in London and New York, and the New York productions of Agnes of God and The Normal Heart). Still, though he is universally praised for his instinctive, sensitive handling of actors and morally complicated subjects, there is the general feeling that at fifty he should have more clout than he does. "Michael's career should be much bigger than it is," says Larry Kramer, the author of The Normal Heart, who recalls that after the play's triumph at Manhattan's Public Theater he couldn't convince the producers in Los Angeles or London that they should use Lindsay-Hogg to direct the productions there, because "he didn't have that kind of reputation."

Asked if he's ever considered himself to any degree a failure, Lindsay-Hogg answers typically, "No, because I also have no goals. What you always want is more choice, more opportunity." He admits that his penchant for keeping his options broad has also rendered him, well, undefinable in an industry which takes comfort in pigeonholes: Is he American or English? Does he belong to rock, television, film, or the stage? Lindsay-Hogg adds that his restless itinerancy has meant he has had to start over professionally each time he's changed cities, and he describes his vocational history as the opposite of that of someone with "an extremely well-organized career, like Mike Nichols. . . . One of the advantages of eclecticism is the great variety of working friends and things which influence you," he continues, "and one of the dangers of it is consolidating a career, which is very hard."

Thus far, his experience with feature films has been sporadic and difficult. After directing Let It Be, the fabled 1970 Beatles documentary, he knew long stretches of waiting for Hollywood development deals to materialize, and his one theatrical release—1977's Nasty Habits, a satiric political allegory set in a convent, starring Geraldine Page and Glenda Jackson—was cut in such a way that Lindsay-Hogg now prefers "to draw a veil over it."

"Very few men get women or the way they are "says Gloria Vanderbilt. "I think he gets women in the deepest sense."

His latest project, The Object of Beauty—for which he wrote the script back in 1980, during a "blue" period (when he was captive to a pay-or-play movie contract that never came to fruition), and which subsequently went through "about forty-eight" potential producers—could raise his visibility level in Hollywood, a fact of which he's well aware. Though the making of the Avenue Pictures release, which was co-produced by the BBC in London's Ealing Studios, was, by all accounts, "a nightmare" (attributed largely to clashes with the BBC bureaucracy and the fact that John Malkovich, its star, was recovering from hepatitis), the film itself is a wellpaced, sharp-tongued, curiously reflective comedy of manners which, like its creator, defies conventional categorization. The story of a pair of footloose, selfish consumerists (Malkovich and Andie MacDowell) living on fast-evaporating credit in a posh London hotel, the movie is unusual in that, as MacDowell notes, "the characters aren't really completely likable, yet you like them for the fact that they're not trying to make you like them all the time." Geraldine Fitzgerald, who says that even as a child her son was strikingly "unjudgmental," remembers his describing Object to her as a story " 'about two worthless people caught in a trap.' And he doesn't find two worthless people unlovable—do you know what I mean?— and he doesn't mind identifying with them." The film is clearly also, as its producer, Jon S. Denny, 4 puts it, the work of a man "somewhat distrustful of achieved ambition and the mythic .. .and more connected to the malaise—which includes madness and disharmony and the seamy side of love."

Life, Lindsay-Hogg thinks, is something you get through on an "ad hoc, improvisational basis," reminting your values as situations change. It would seem to be against his nature to commit himself to any single path, or to saddle himself with any of the expected appurtenances of a middle-class life—a permanent home, children, even a wife. (He was married briefly, from 1968 to 1971, to the Irish television researcher Lucy Davies, who is now the wife of Lord Snowdon.) "People get married, then have the children and then have the house and then have the weight—legal weight, financial weight. And suddenly they're tired. And that was their life."

And though he's known to work swiftly and efficiently under pressure, he prefers the luxury of postponing decisions for as long as possible. "He's not capable of making a decision on his own," says Nona Summers. "He's made many decisions for his career that I think weren't real decisions; they were the result of other circumstances." Lindsay-Hogg ascribes this in part to his belief that ''my reflexes are backward" (he couldn't read until he was nine and is still unable to drive a car), but, he adds, "I always think I might be a little smarter two seconds from now than I was two seconds ago.... I always try to see all the angles."

It's a tendency that translates, sometimes exasperatingly, into his personal life. "He was never able to let go of all the bloody girlfriends," says Summers, who is still nettled by his continuing tradition of spending Christmas with Jean Marsh. "When I first met him, he would ring, let's say, the previous three to me to make sure they were all right. He can't bear to let go of anything." Similarly, a woman who had a short affair with him remembers his saying to her, " 'Oh, when you're eighty, we'll run into each other and make love,' like it was going to be unbroken."

While the same woman describes Lindsay-Hogg as "emotionally irresponsible," the director, who remains a good friend of his ex-wife as well as Marsh, counters, "Many people think that love is like a piece of pie that you take from one person and give to another person. I always think that if you find someone else that you care for you just make a bigger pie. I would never take away the feeling that I have for someone and give that to someone else."

He is, in fact, most comfortable with women—a trait he attributes to having grown up in Los Angeles during World War II, a time when most men were away and his playmates on the Santa Monica shore were largely female, the daughters of such neighbors as the film star Constance Bennett, Virginia Welles (Orson's first wife), and Hearst publisher Richard Berlin. Though he's developed strong professional friendships with such disparate fellows as Jeremy Irons, Mick Jagger, and Lome Michaels, "men," says Summers, "make him nervous." Lindsay-Hogg concedes his only true friend at a given moment "is usually the woman I am entangled with in some emotional way." Today, in writing screenplays, he thinks he's better with female characters, and is known to tenderly elicit sterling performances from actresses ranging from the late Geraldine Page, whom he describes as one of the few geniuses he's ever known, to Greta Scacchi, whom he directed in the BBC television film Dr. Fischer of Geneva. "I think his ideal ambition," says Summers, "would be to live in a converted Armani showroom as his house, with the possibility of directing the greatest films with as many women in them as possible—all of whom would be madly in love with him—and to have me waiting at home."

He also has the romantic reputation of a low-voltage, more subtle Warren Beatty—a man who seems, as one ex-girlfriend put it, perfectly able to address women's images of themselves. Nona Summers was recently married, to British art dealer Martin Summers, when she ran into Lindsay-Hogg at a New York dinner party in 1981, but, she says, "unfortunately, when I looked at him, I knew I was in big, big trouble. It was the first time anyone said to me 'I love you' at the same time I said it to them." "I do think he hooks into women's psyches," says Gloria Vanderbilt, who dated Lindsay-Hogg in 1979. "I feel very, very few men get women or the way they are. And I think he gets women in the deepest sense. And that, of course, is very seductive." Jean Marsh says Lindsay-Hogg is innately intrigued by, and sympathetic to, all women, but adds, "I don't think he quite understands how much women do actually fall in love with him, and then when he withdraws his attentions—not deliberately, but like going to another country— the woman can feel the light's gone out. "

"Odd" is one of Lindsay-Hogg's favorite adjectives; it also crops up frequently in other people's descriptions of him.

Jake, the womanizing, homeless hedonist with a distaste for commitment and a fondness for cigars and expensive shoes in The Object of Beauty, would seem to be a self-portrait. But while Lindsay-Hogg admits similarities (like Jake, he's always found that "money seems to go out in a way that's inescapable, like the Tide in a wash"), he insists he identifies far more with a character in the film's contrapuntal subplot: Jenny, a penurious deaf-mute who "knows bouts of loneliness and times when she'd feel she doesn't quite know what her life is ever going to be."

Though Summers describes him as "still a little boy, really," Michael Lindsay-Hogg seems, in some ways, to have been a peculiarly adultlike child. Geraldine Fitzgerald remembers him at the age of seven saying, "Prove to me that I am a child.... I could be an old man dreaming of my childhood, couldn't I?" She responded by telling him to "grow up fast, prove to me that you're not an old man dreaming of his childhood."

It was advice he was eager to take. Because his father—whom his mother divorced when he was five to marry the New York businessman Stuart Scheftel—was with the Irish Red Cross during the war, he never really knew him until he was nearly grown up. And though he was close to his mother, who moved to New York with him when she married Scheftel, she was working in films throughout most of his formative years, and he was raised largely by an Irish nurse, "a kind of bigoted Catholic, who would tuck me in saying, because my parents were divorced, 'Don't you worry. Your mother and father will go to hell, but you'll be all right.' " The fact that he was fat (a problem which would persist, erratically, into his twenties), slow-moving—with vain longings to be a baseball player—and unable to read until he was nine made him an obvious target of fellow students, and he grew up more at ease with adults and acutely dependent on his nanny. "I don't think I went out on the street alone until I was nine," he says. He remembers "sitting on a school bus when I was eight, and thinking, Well, you're going to go through another eight years of this, until you're old enough to be on your own. It was like being in prison."

He attended Choate, the private boys' school, and adapted the curled-fringe hairstyle Marlon Brando had sported in Desiree in hopes it might make him more attractive to girls; in fact, it only alienated school authorities and classmates, who "used to come into my room at night and try to cut it off with sheep shears." He recalls visiting his mother during rehearsals in New York and finding "actors were the first people to treat me, if not like an adult, like some kind of weird equal." When, at sixteen, he got a job as an apprentice at John Houseman's repertory company in Stratford, Connecticut, he felt adulthood had finally arrived.

Deciding he'd become an actor, he thought he should change his name and showed his mother a list of proposed alternatives. They included Michael Welles, since Orson Welles "had always been very kind to me,'' letting him attend rehearsals in New York and later using him in his London production of Chimes at Midnight. His mother told him "that might not be a good idea," which was how, at sixteen, he learned of the Welles paternity rumors. Fitzgerald has always denied the story. "We had a great flirtation that didn't come to much," she told Rex Reed in a seventies interview. And she said she thinks the story began because she stayed in Welles's house in Hollywood when she was pregnant with Michael. "Also," Lindsay-Hogg adds, "Orson didn't not contribute to this idea." He remembers being told by the director Henry Jaglom that Welles, in his later years, taped Brideshead Revisited and would "sit in front of the television, trying to figure out which sequences you directed." And he admits his physical resemblance to the late director: "I think that my features, because of the relationship of what I got from my mother and father, tend weirdly to look like his." The similarity is accented by his predilection for cigars. "Michael plays on it," says the writer Joan Juliet Buck, who dated Lindsay-Hogg in the mid-seventies. "He'll let you know [the rumor] and then deny it, but it's definitely factored in."

Once he'd decided to enter the theater, life moved quickly. After a year at Christ Church College at Oxford, he established, at twenty-one, his own summer repertory theater in upstate New York with his friend Peter Bogdanovich—a somewhat anxious experience, because they fell in love with the same girl (Polly Platt, whom Bogdanovich subsequently married). Lindsay-Hogg moved to Dublin, to work as a television floor manager, successfully directed a play (starring Milo O'Shea) at the Dublin Theatre Festival, and got to repeat it for television by telling the reluctant TV executives that he owned the rights to the play—a lie. "There's a period in your life when you do lie, because there's no other way to get on." Further falsehoods, about his directorial experience, secured him a job with the BBC in London, and by twenty-four he was the principal director on Ready, Steady, Go!, the popular showcase for such performers as the Animals, the Kinks, and the Rolling Stones.

With his custom-made gingham shirts and double-barreled name, LindsayHogg was a rarefied anomaly among the rock 'n' roll brigands. But his ability to find visual equivalents for the music, with his novel use of zoom shots and extender lenses, and his own distinctive breed of flamboyance (Jean Marsh remembers that when she met him, on a television shoot around that time, he was wearing a pink shirt and raspberry shoes) earned him the respect of the industry's stars. His work in early videos for the Stones ("Jumpin' Jack Flash") and the Beatles ("Paperback Writer," "Hey Jude") reached a climax in his direction of Let It Be, a feature documentary which subversively captured the tensions among the Beatles in their twilight days as a group.

"I don't think he quite understands how much women do actually fall in love with him," says Jean Marsh.

Lindsay-Hogg remembers the midsixties in London as a heady, exhilarating period: smoking his first joint with Stones manager Andrew Oldham in the back of a Rolls-Royce "the size of this room" on his way to meet the group; setting up a meeting between the Doors' Jim Morrison and the painter Francis Bacon at a Soho drinks club; being introduced to the Beatles—whom he describes as a tight, insular group, suspicious of outsiders—at an absurdly lavish banquet in a recording studio. "He was crazy about it," says Marsh. "He absolutely adored Mick and Keith—it was almost as if he had a schoolboy crush on them, that they could do the things he wouldn't dare to do, perhaps. . . . Oddly, he actually isn't musical at all. He can't sing in tune, can't really remember a song, and doesn't dance very well."

Lindsay-Hogg says he largely avoided drugs—not for moral reasons, he adds quickly, but because he prefers drinking: "I like what it does, and I can judge the penalty." He has continued to work with rock musicians—directing filmed concerts of Paul Simon and Neil Young, touring as a TV adviser with Jagger in Japan in 1988—and describes the experience as reminiscent of Saint-Simon's memoirs of the court of Louis XIV. "You know, did the emperor sleep well, what did he have to eat, what are his stools like, did he get to bed late? All of this, because you're so influenced by the mood and the capriciousness of the emperor/emperors. ' '

While he was in Ireland, LindsayHogg had fallen in love with Lucy Davies, and lived with her in London in the mid-sixties. As his career prospered, the relationship foundered, and Davies left town for eight months. It was during that period he met Jean Marsh, and although he married Davies when she returned, "the connection of those circumstances proved very rocky for everyone for a few years. But then Lucy and I didn't stay married, and I moved in with Jean. But it wasn't easy. And the fact that Lucy and I are still close is really a kind of testament to her extraordinary capacity for charity and forgiveness."

Says Marsh of their eight years of sharing a flat, "In no way did we ever say, We're going to set up shop together. We just drifted into it, and we drifted out of it. In a sense, I might have got the best of him, because it suited him at the time. I don't mean this in a pejorative sense, but he's even more of a loner now."

After a brief, frustrating period in Hollywood in the early seventies—when he was commissioned to write a script about a rock groupie, which he self-sabotagingly managed to turn partly into a satire of the executives who'd requested it, "because I hated working with MGM so much"—Lindsay-Hogg returned to London to reforge his career in British television. He soon demonstrated his taste for dramas with knotty subjects which emphasized problems over solutions—things, as he puts it, "with a certain risk to them." It's a tendency evident in his unflinching production of Trevor Griffiths' Through the Night, the story of a woman undergoing a mastectomy; in such stage work as the London and New York productions of Whose Life Is It, Anyway?—about a paralyzed man (Tom Conti) who fights for the right to end his own life—and Larry Kramer's revolutionary play about AIDS,The Normal Heart, in New York; and in his adaptations, for American TV, of Master Harold and the Boys, Athol Fugard's study of South African racism, and another AIDS drama, As Is. But he's probably best known for his more lyrical work on Brideshead, which he cast and directed the initial episodes of, but was forced to abandon after five months of shooting—to his enduring sorrow—by the unfortunate convergence of a technicians' strike in England and a contract for yet another movie in Hollywood which was never made.

He is generally adored by actors, who cite his compassion, patience, and the expansive freedom he allows them. "The thing that's so nice about him is he allows everybody to approach their potential,'' says Tom Conti. "He doesn't obstruct as a director. . . . He's wise enough to think that he doesn't necessarily know best.'' Having been an actor as a teenager, Lindsay-Hogg says, "I know sort of what they go through. I admire them very much, and I think they're very brave." He is accordingly fiercely protective of them. Jean Marsh remembers his dining with cast members in an expensive hotel restaurant and throwing a table across the room when a snobbish waiter refused to serve one of them a postprandial tea (considered "common" after-dinner fare in England), saying, "How dare you speak to one of my actors like that?" "Once that was done, he was quite happy," says Marsh. "He just left the room and made a phone call." And when, during the New York rehearsals of the Mary Tyler Moore version of Whose Life Is It, Anyway?, producer Emanuel Azenberg fired a young actor without LindsayHogg's consent, the director stormed into the theater's lower foyer and trashed it. (The play's still photographer took a picture of the devastated lobby, which was sent to LindsayHogg as a present.)

His temper, friends agree, has mellowed with age, though off the set he's still given to dramatic outbursts. Summers recalls that during preparations for The Normal Heart—when she was sharing an apartment with Lindsay-Hogg in New York—an actor in the play told her, " 'God, it must be wonderful to live with Michael. He has such an aura and such Karma about him, he's so calm. . . ' And I looked at him and said, 'Oh, really?' I was trying not to spit, I was laughing so hard." She believes the director has stored up a reservoir of anger he's never come to terms with. Yet he is also described as a man almost excruciatingly sensitive to the problems of others. Marsh says, "If you want to win Michael, be ill. Just tell him there's something the matter and he's there for you."

Today, Lindsay-Hogg remains a man without a home, addicted to travel, and happiest, perhaps, in hotels and urban environments. The countryside baffles him. "He doesn't know the names of animals," says Marsh. "He once came rushing into my house [in the country] saying, 'There's a very, very old rat in the garden.' And it was a toad. He thought it was a rat with a lot of lines on its face." And though he likes to think of himself as a gypsy and a man who is "pretty possession less," he always travels with vast quantities of luggage, and Marsh, for his birthday, gave him half of her attic to store things in. He is a passionate collector of boots, rocks, luxurious toiletries, and Armani men's wear. "The reason we don't live together," says Summers, "apart from the fact that I have no proper baskets intact—they've all got holes in them from where he's lost his temper and kicked them—is because I would have to move out of my house to make room for all his clothes."

But his greatest folie is for postcards. He says he's seldom more content than in art galleries or museums—paintings for him offer "some kind of order in a frame which you can take in like a drug"—and he returns from them with stacks of cards of drawings, paintings, photographs. They cover every surface of his living room, along with a vast assortment of colored pens and pencils meticulously arranged in jars. While he tailors two other scripts he's been working on and waits for the response to Object—and to learn where his next job, and home, will be—he's been teaching himself to draw.

They are strange, singular sketches, at once childlike and worldly, affectionate and sardonic. He showed me a portfolio he's been working on of nude men and women eating bananas, which interests him "because the sex of the person doing the thing alters the whole thing, of course; it has a whole different resonance." One drawing, taken from a detail in a Renoir painting, shows a blind man seated at a cafe table, with a sighted couple hovering over him—whether with helpful or sinister intent is unclear. On it, Lindsay-Hogg has written the caption "Come with us, it'll be O.K."

"1 think that's probably an accurate view of my sense of life," he says when I ask him about it. "It might be O.K. It might not."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now