Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowNORA'S ARC

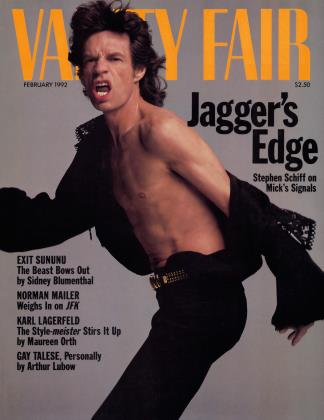

Movies

Writer Nora Ephron has always survived hard-luck stories by turning them into hits. And her directorial debut, This Is My Life, looks like a three-hankie classic

LESLIE BENNETTS

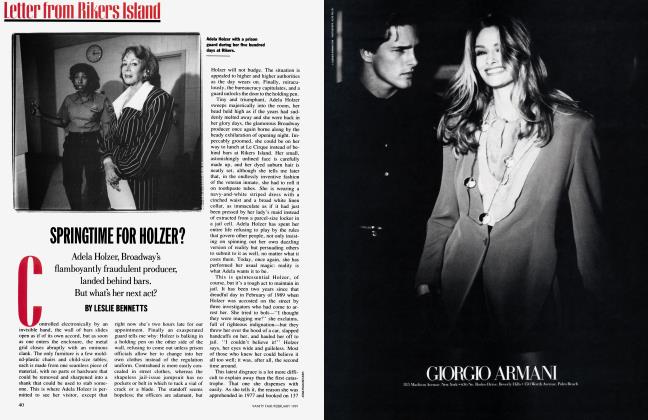

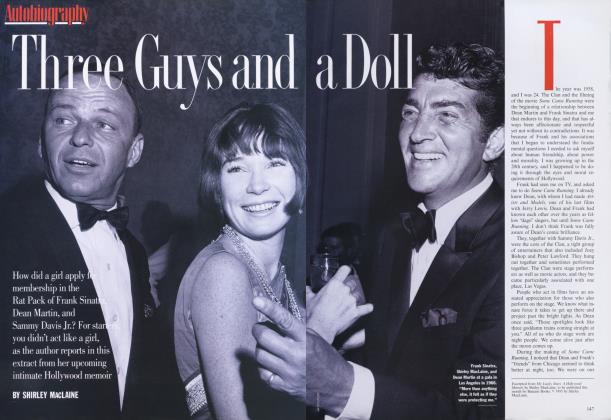

She sits quietly in the dark, her eyes never leaving the movie screen as she sips jasmine tea made from the cache of tea bags she always carries with her, lest she be forced to drink some inferior brew that doesn't satisfy her uncompromising palate. Nora Ephron has always been someone who not only knows exactly what she likes but arranges, with precision and forethought, to get it. Up on the screen in front of her, a long black limousine is cruising through the neonchoked streets of Las Vegas; as it passes a giant marquee advertising "Dottie Ingels," a little girl pops through the car's open sunroof, throws up her arms, and yells, "That's my mom!" Over and over again, a technician sitting at a vast electronic console runs the same piece of film footage, trying out different versions of the snippet of dialogue and fiddling with sound levels as everyone in the room listens intently. Ephron has been closeted in this midtown Manhattan mixing studio for weeks, and at times the process is excruciatingly tedious; it takes nearly two hours to decide these three words of dialogue. She is having the time of her life.

"The hugest smile I ever saw was when Nora said 'Action!' for the first time," says Julie Kavner, the star of Ephron's new movie, This Is My Life. "It was a smile of complete pleasure. She loves to be able to control things. Francis Coppola said that being a director is one of the last dictatorships you can have in an increasingly democratic world. Without being a dictator in the evil sense of the word, Nora is, in a positive sense. I think Nora was bom to direct."

Indeed, in many ways Ephron has been aiming for this moment ever since her childhood in Beverly Hills as the daughter of two successful screenwriters. Her own time has finally arrived. At the age of fifty, after a dozen years of writing screenplays for other people and picking up a couple of Academy Award nominations along the way, Ephron not only wrote This Is My Life with her sister Delia but directed it as well. Based on a Meg Wolitzer novel called This Is Your Life, the story follows the sudden rise to fame of Dottie Ingels, a single mother who works in the cosmetics department at Macy's on Queens Boulevard but who is determined to make it as a stand-up comedian, despite the conflict between the demands of her career and the needs of her two daughters. Ephron may be new to the director's chair, but she was hardly reticent about her claim to it in this case. "When Lynda Obst sent me the book, I knew I absolutely could direct this, and, further, that I was the only person who could direct it—that there was no one working as a director who was going to make a movie about being a single mom with two kids and the pull between kids and career,'' says Ephron, whose friend Obst produced the film. "Who's going to make this movie? I was without any question the logical person to make it. I grew up with a mother who worked. It's a movie about sisters, and about using your life as part of your work, and what the effect is on your family when you do that. On every single level it was my movie.''

It is, to an eerie extent, her life as well. Dottie Ingels horrifies her sixteenyear-old by embroidering on a real-life mother-daughter conversation to get a laugh on a television talk show—but Ephron was already providing her parents with material by the time she was two years old, when they wrote a play about her. They managed to get a Broadway hit out of Nora's college career when they used her letters home from Wellesley as the basis for another play. (They never asked her permission, but despite many years of therapy she claims she didn't mind a bit.) As a magazine writer, Nora became famous for writing about everything from how inadequate her own breasts were to the progress of a case of crabs passed around a circle of licit and illicit lovers, certain of whom were so clearly based on the author's intimates as to cause them considerable distress. However, Ephron's propensity for cannibalizing her own life didn't become a cause celebre until the spectacular demise of her second marriage, to Carl Bernstein. At first their union seemed a coup for them both: Watergate hero marries New York sophisticate. For a while they were the toast of the Eastern shuttle and the highest-profile media couple around, except perhaps for their very good friends Ben Bradlee and Sally Quinn. Then Carl launched a torrid affair with the wife of the British ambassador while his own wife was pregnant with their second child, a son born two months premature after Carl informed Nora that he was madly in love with his inamorata. Although she was devastated, Ephron didn't grow up in Hollywood for nothing. No matter what happens, her mother was fond of saying, "It's all copy.'' Nora promptly called the columnist Liz Smith to announce that she and Carl were through, and went on to turn her marital debacle into a best-seller, a Mike Nichols movie, and a lifelong albatross around the neck of the cad who was foolish enough to betray her. Dottie Ingels may be a minnow in the school of confessional revelations, but Nora Ephron is the great white shark.

On its deepest levels, the movie is about Ephron and her greatest strength-her ability to take whatever cards life deals out and turn them into a winning hand.

Mnvips

In an odd twist, the plot of her new movie parallels what happened to Ephron while making it; this time around, life imitated art. As Dottie Ingels, who has devoted herself to her kids for sixteen years, embarks upon her intoxicating ascent, she is away from home more and more; her children are furious, and their resentment finally explodes in a family free-for-all. "This is the first time I have been away from you in your entire life!'' Dottie wails. "Don't I have a turn? Isn't it ever O.K. for me to have a life?" If the problems presented by Dottie's heady new opportunities weren't drawn directly from Ephron's experience, they certainly anticipated it. For the last dozen years, despite her increasingly high-powered movie career, she remained a notably conventional mom, working in a little office behind her bedroom and retiring to the kitchen to start making dinner when her kids came home from school. Last spring, however, she spent ten weeks on location in Toronto shooting This Is My Life. Her sons, who are now twelve and thirteen, visited on weekends and made guest appearances in the movie dressed up as trees quoting T. S. Eliot in a school play. "I'm very wary of talking about my kids, because I do feel it's their life," Ephron says carefully. "But they were quite shocked that I was going off to do this movie. I thought I was giving my sons the experience of having a working mother, but on some level they had a very traditional mom. I'm not going to say I was June Cleaver; obviously I was divorced. But for most of their lives, I have been home. All this stuff about quality time and how kids are happy if their mother is happy—that's all nonsense. They just want you to be there. When you're a working mother, basically everything that happens that's good news for you is bad news for your kids."

There is more than a hint of defensiveness in Ephron's account of her decision, as if she has rehearsed the litany of good reasons a hundred times to placate her own conscience before reciting them for someone else. "The kids were eleven and twelve before I went away, and it's not as though I went to Australia," she says a bit plaintively. While she was gone, the boys spent time with both their father, whom they see regularly, and stepfather. "I was an hour's plane ride away, and they had the ability to come whenever they wanted." She sighs. "It all worked out all right, and we'll find out someday whether I did something unspeakable to them."

According to her ex-husband, she already has; after the publication of Heartburn, her autobiographical novel, Bernstein spent years in court wrangling over Ephron's right to make it into a movie. He has always preferred to characterize this battle as a defense of the rights of his children against exploitation by their predatory mother. However, his chief concern seemed to be how he himself was portrayed on-screen; he maintained he was worried about how his children would see him when they grew up. Because the divorce settlement was tied to the acrimonious dispute over Ephron's screenplay, it took more than five years to work it all out, and the movie was severely compromised in the process. Bernstein later boasted that he accomplished his objective, which was to ensure that, despite the box-office power of Jack Nicholson and Meryl Streep, Heartburn "sank like a stone." His crusade has also had an enduring impact on Ephron's work: she is legally enjoined by the terms of her divorce settlement with Bernstein from using anything about their life together or the children as material in her work.

When Nick and Nora got together, the cynics wondered whether she would stay with him: "'Is he famous enough?' was the question."

If Ephron has been restrained from using the specifics of her own family life to fuel her writing, she has certainly succeeded in finding the universal resonance in the story of one frumpy Jewish hausfrau from Queens. Some critics will undoubtedly hail the ending of This Is My Life as heartwarming, while others will dismiss it as sentimental, but it is hard to imagine a working mother who won't identify with Dottie's dilemma; I personally cried off all my eye makeup. However, the movie doesn't pretend to offer any pat solution on how to balance the conflicts between career and kids. "There is no answer to that question; that's what this movie is about,'' says Ephron. "You just have to make it up as you go along and hope you don't screw it up too horribly.''

For a first-time director, Ephron has exuded a remarkable confidence of late, manifesting none of the pre-opening jitters one might expect; she brought the film in on time and, by today's industry standards, quite cheap, at $10 million. She is proud of what she's accomplished: "I think if you're a woman and you see this movie you say, 'This movie, even if it's just one second of it, is about me.' "

On its deepest levels, of course, it is about her, and about her greatest strength —her ability to take whatever cards life deals out and turn them into a winning hand. If you're not pretty, make jokes about it and everyone will love you for your sense of humor instead. If someone humiliates you, return the favor in spades and get rich doing so. If your fabulously brittle and sophisticated mother wasn't as sympathetic at home as she was impressive in public, forge your childhood sorrows into steel. Unlike her mother, whose well-concealed weaknesses led her inexorably to a tragic end, Nora Ephron is indomitable. She learned her lessons well. Her parents were a hard act to follow, but she has already outdone them.

On a bright winter morning, sunlight streams in through the soaring windows of Ephron's cheerful Upper West Side kitchen. The fact that her sprawling eight-room apartment has been described as "baronial'' might seem excessive somewhere other than Manhattan, but by New York standards even her kitchen ceilings are lofty enough for a ballroom. Ephron has lived here with her two sons ever since she and Bernstein broke up at the end of 1979; for the last nine years, the household has also included Ephron's third husband, Nick Pileggi, the author and screenwriter.

When Nick and Nora got together, the cynics wondered whether she would stay with him: " 'Is he famous enough?' was the question," reports one mutual acquaintance. Then Pileggi hit the best-seller lists with Wiseguy, prompting Bernstein to comment in Playboy, "Usually, when that happens, Nora gets married. The trouble starts when you slip off the best-seller list."

Nora did get married, but by all accounts the trouble hasn't started; the Pileggi-Ephron marriage gets rave reviews from virtually everyone who knows them (and, besides, Pileggi has since scored a big success with the widely acclaimed screenplay he wrote with Martin Scorsese for GoodFellas, the movie based on Wiseguy).

The couple's domestic setup is as cozy as their relationship. Right now Pileggi is ensconced in his office across the courtyard from their apartment. Ephron is at home, curled in a chair at her kitchen table, picking thoughtfully at a dish of dried cherries from Zabar's and contemplating her life, or at least those portions of it she is willing to talk about. For a writer who has specialized in titillating personal revelations on paper, she can be curiously opaque in conversation; Ephron doesn't give anything away for free, and what she does share has long since been processed and packaged as part of the ongoing mythology of her life. "I've written about every thought that ever crossed my brain," she says breezily.

Before she even started committing her thoughts to paper, her parents were doing it for her. Born in New York and transplanted to Beverly Hills at the age of three, Nora was the eldest of the four daughters of Phoebe and Henry Ephron, who began to collaborate as playwrights and parlayed their success onstage into a lucrative career as screenwriters. Their credits included Carousel, There's No Business Like Show Business, Daddy Long Legs, Desk Set, The Jackpot, and What Price Glory?, and their movies featured an array of stars that ranged from James Stewart and Ethel Merman to James Cagney, Fred Astaire, Marilyn Monroe, Leslie Caron, Katharine Hepburn, and Spencer Tracy. The Ephrons' first play about Nora, Three's a Family, ran for 495 performances and played for a year and a half in London; years later, when she went off to college, they wrote Take Her, She's Mine, and Nora found herself portrayed on Broadway by Elizabeth Ashley under the direction of George Abbott. The Ephrons' life was a glamorous one, and not without its domestic comforts; Phoebe liked to wear stylish suits with big shoulder pads and tool around in her Studebaker, but when she was at home she read cookbooks in bed, and if she didn't exactly make dinner herself she always made sure the household had stellar cooks. Nora remembers her childhood as if it were a wonderful movie: in the eulogy she delivered at her mother's funeral, she talked about singing rounds at the dinner table and playing charades afterward, and about how much fun it all was. "There was always a great deal of laughter," she said.

"I thought I grew up in a sitcom, and my youngest sister, Amy, thinks she grew up in a loony bin," Nora says.

However, one of the underlying themes of This Is My Life is the variable nature of reality in any family, given the differences in perspective among individual members. The Rashomon quality of the Ephrons' shared history is dramatic. "I thought I grew up in a sitcom, and my youngest sister, Amy, thinks she grew up in a loony bin," Nora says. It took the girls years to realize that their mother drank too much, but by the time Nora went away to college the problem had become acute. "Mommy was this sort of closet alcoholic, where her best friends didn't know she drank," says Amy Ephron, who is eleven years younger than Nora and who, like three of the four sisters, writes books and screenplays. "She had this perfect personality, and then she would have one drink, and there would be this other person there. My father was drinking, and it was horrible; my parents used to scream all night. I remember Nora coming home from college one year and she suddenly realized what was going on. We got different parents; she got the upswing, and I got the downswing." According to Nora, Henry Ephron is a manic-depressive and has spent time in mental institutions; Phoebe was hospitalized for the last couple of months of her life, and she died at fifty-seven of cirrhosis of the liver. But even as she lay dying, she never lost her edge. When her eldest daughter went to visit her in the hospital near the end, Phoebe turned to her and commanded, "Take notes, Nora, take notes."

Ephron defends that ethos as a highly productive one, which in her case it apparently was. "That's an important lesson to learn—that what seems horrible to you today can be reborn as a funny story if you work hard enough at it," she says. "I think it's healthy for someone to point out to you that things might not be as tragic as you believe and there might even be some way to turn it into something." Indeed, in Heartburn, Nora wrote that her mother drank until "one day her stomach swelled up like a Crenshaw melon and they took her to a very fashionable hospital for rich people with cirrhosis and the doctors clucked and said there was nothing that could be done. . .. She lay there slowly dying, with my father impatiently standing by. 'Pull the plug,' he would say to the doctors. ... Suddenly she opened her eyes and looked at me. 'I just screwed Darryl Zanuck on the remake,' she said, and gave a little croak...and died." But when the nurse pulls the sheet over her mother's face, the corpse suddenly whips it off and shouts, "Ta-da!" Convinced she has come back from the dead, she files for divorce, goes to New Mexico to find God, and marries a guy named Mel who believes he's God and takes her for every penny she's worth. The real Mrs. Ephron didn't recover or find Mel, but if her death was harrowing, in Nora's hands it played like a stand-up routine.

Indeed, that was how she had learned to process everyday life. The Ephrons' dinner table was a nightly bonanza of bons mots, with everyone vying for the title of cleverest, but the competition didn't faze Nora—probably because she won without even trying. "You were supposed to tell little stories, and funny was better than not funny," she says. "Delia said, 'Everyone used to sit around the table and you were expected to tell stories and it was really grotesque.' I thought it was great. The truth is it was harder for my younger siblings than it was for me." The third-bom Ephron daughter, Hallie Touger—who has opted out of the family business to become a manager at a computer company in Massachusetts—remembers the competition well. "You had to claim your airspace," she says dryly. "It was a lot like the Algonquin Round Table."

Small wonder that Nora grew up determined to become Dorothy Parker. Even when she was a child, no one doubted her potential. "She was a star," attests Hallie. "She's always been a star. She was Most Likely to Succeed in her senior class; she's always known what she wants and how to get it."

That, of course, was the behavior rewarded by her mother. When things weren't going so well, Mrs. Ephron wasn't interested. "If you went to a dance where no one wanted to dance with you, my mother was not the person to talk to about it," Nora says haltingly, as if this is difficult to admit. "Where did I go for sympathy? I don't know where I went for sympathy. I don't think there was a whole lot of sympathy." As an adult, she herself has always had a reputation for ruthlessness, but it's easy to see where it comes from; she internalized her mother's voice a long time ago. "Nora doesn't like whining," says Hallie. "I remember telling her about all the reasons I couldn't get a summer job once when I was a teenager, and she said, 'This is ridiculous. If you want something, go get it; don't tell me all the reasons why you can't do it.' It's hard for a younger sister if you just want sympathy, but she motivated me to stop looking for reasons why this or that was happening and to put the blame in my own hands."

Outside the Ephron family, there were other pressures, particularly for a skinny, dark-haired, flatchested young woman who was never going to dazzle anyone in the land of blond surfers with her looks alone. Later on she would get considerable mileage out of that persona; she called her first published collection of essays Wallflower at the Orgy. But as a teenager, when she spent four years sleeping on her back, bought a Mark Eden bust developer, and splashed cold water on her breasts every night because some French actress had said in Life magazine that that was how she had acquired a perfect bustline, she had yet to transmogrify the insecurities into a commodity. "When you go to Beverly Hills High School, you're graded on one thing: your allure," says a fellow graduate. "Physical appearance is all that counts; it's not like the East. I think Nora's always projected herself as the ugly duckling. Her wit made up for not having the beauty; it was 'Don't mess with me.' She's one tough cookie."

Ephron has always been blunt about the urgency of her desire to escape Southern California. "I grew up in L.A. knowing that if I didn't get out of there I would die," she says. She proceeded from Wellesley directly to the big time; a reporting job at the New York Post led quickly to writing assignments at Esquire and New York magazine. By the time Ephron had made a name for herself as a writer in New York, she was equally famous for her merciless tongue. "One night some guy at a party had a really dumb date and she was trying to impress everyone and she said something about 'the Reds,' " recalls Richard Cohen, a columnist for The Washington Post. "Nora went crazy. Five minutes later there was nothing but tissue on the floor; the woman had ceased to exist." Ephron will light into anybody, from the limo driver servicing her last wedding to the president's Secret Service detail, but some of her nastiest thrusts are reserved for other women—especially those who are beautiful as well as smart and successful. "One time a bunch of us were at a party in the Hamptons, and Gloria Steinem was wearing this backless dress," reports a fellow guest. Steinem is famous for being as thin as a stick, but that didn't offer any protection. "The minute she left the room, Nora hissed, 'Did you see the fat rolls on her back!' " says the guest.

"If you went to a dance where no one wanted to dance with you, my mother was not the person to talk to about it," Nora says haltingly.

Ephron claims she's long since gotten over any early insecurities about her looks, but her behavior sometimes suggests there are enduring scars. When Diane Sawyer married Mike Nichols, who directed Ephron's screenplays for Silkwood and Heartburn, the beautiful blonde newscaster became a target as well. At a party celebrating the nuptials, Ephron delivered a toast to Sawyer that some people thought funny but others found extremely mean. Ephron's disquisition on "How to Keep Mike Happy" focused mainly on food and on Sawyer's notorious lack of interest in such domestic arts as cooking—a skill for which Ephron herself is renowned. She also managed to get in a dig about Nichols's having gotten married in a church, since he and Ephron are both Jewish and Sawyer is not.

Ephron is well aware of her reputation as a one-woman neutron bomb, but she doesn't seem particularly perturbed by it. Indeed, in some ways it has served her quite effectively. "I know that people are afraid of me," she says evenly. "It's not something I worry about too much. Sometimes it's helpful. The opposite of it is something I'm not interested in, which is that people think they can walk all over you—and when you're a screenwriter, people think that anyway. I'm not running for office here; if I were, it would be a problem." Besides, she says, she doesn't even go in for public evisceration these days: "I don't do much of that anymore. I've definitely changed. I think I'm positively mellow." Behind her drooping eyelids, her eyes glitter dangerously; one feels about as safe with Ephron as a small bug might sitting in front of a motionless but hungry lizard with a very long tongue. She yawns. "You get older and you let them go by every so often," she says languidly. "You don't always say what you think. It's important to know what you think, but not always to say it. You spend a lot of time when you're younger getting in touch with your feelings—I've spent a billion dollars getting in touch with mine—but I've learned that just because you're having a feeling does not put you under a compulsion to express it."

Some of Ephron's closest friends swear that she really has toned down her vitriol and people just haven't realized it yet. "She's still living with this old reputation of being the fastest gun in town," says Amanda Urban, vice president and co-chairman of the literary department at ICM. Others maintain that Ephron doesn't do anything to the rest of the world that she doesn't also do to herself. "She's got this X-ray vision that's quite scary," says Sally Quinn. "It's sort of a truth laser beam. She sees right through you; you can't get away with anything with her. I think what scares people is they feel denuded by her. But she's as ruthless about herself as she is about anyone else. She can look at herself and say, 'I'm this and this and this,' talking about her own faults and idiosyncrasies, and it will take your breath away. She sees things the way they really are."

The less charitable interpretation is that Ephron sees only the darker side of things. Even among the powerful, it's amazing how many movers and shakers use the same words: "Nora terrifies me," says one formidable woman. "Nobody's safe," adds another. "You just don't want to be in her mouth, particularly when she's with one of her pals." Another well-known New Yorker mentions the force field generated by Ephron and her clique, and says, ' 'A lot of us just keep our backs to the wall and circle around them with a lot of trepidation, while remaining very friendly on the surface. Nora is the last person I would want as an out-and-out enemy."

Although a large proportion of such complaints tend to come from other women, the memory of Heartburn lingers, casting a powerful chill over men. A New York tabloid recently featured Ephron as one of "Ten New York Women Who Make Men Nervous," describing her variously as "the patron saint of the modem scorned woman" and as "Medea." "I think in some way my writing that book was a certain kind of male nightmare come true," Ephron muses. "Glenn Close in Fatal Attraction was one kind of male nightmare: 'What if I slept with a woman and she got pregnant and mined my life?' I think I was some other form of male nightmare: 'What if I got involved with a woman and told her all my innermost secrets and she went off and wrote a book about it?' "

In Heartburn, Ephron portrayed the husband as cold, callous, and staggeringly self-absorbed, not to mention promiscuous. "The man is capable of having sex with a Venetian blind" was probably the most quoted line in the book. Nor was Bernstein the only ex-husband who got burned; the novel also offered a scathingly funny portrait of the protagonist's first husband: stingy, compulsively neat, and obsessed with his hamsters, Arnold, Shirley, Mendel, Manny, and Fletcher. When Arnold died, his grieving master had him cryogenically frozen, brought him home in a Baggie with a rubber band around it, and interred him in the freezer. (It turns out that the humorist Dan Greenburg, Ephron's real-life first husband, had cats, not hamsters, and didn't go in for cold storage. However, the part about his sleeping with Nora's oldest friend is true.)

Ephron's motivation for writing about such episodes is considerably more complex than the simpleminded revenge suggested by her critics, although of course public vengeance has always been a large part of the mix. "Everyone uses stuff from their life," she says impatiently. "There is barely an American writer in the last fifty years who has gotten divorced and not written something about it, so give me a break. I just don't see anybody attacking any of them—but they're all men. It was quite fascinating to me that when a woman did it, everyone started worrying terribly about the poor children." There were practical considerations as well; when she and Bernstein broke up, she needed money. More important, however, it was the image of victim that Ephron couldn't live with. "Nora wasn't going to be the pitiful jilted woman," says Sally Quinn. "She set a very good example of a woman who said, 'Not only am I not going to be a victim, but I'm going to take this tragedy and do something productive with it.' She made money on the book, she made money on the movie, and I think it showed that she wasn't going to be taken advantage of."

Ephron is well aware of her reputation as a one-woman neutron bomb. "I know that people are afraid of me.... Sometimes it's helpful."

For in publicly humiliating her on such a grand scale, Bernstein had touched the deepest nerve of all: the girl for whom getting approval meant always being the cleverest one in the room was made to feel—and, worse, to look—stupid. "I think probably the feeling I like least in the whole world is feeling dumb," Ephron says grimly. "If your mom loves you for being smart, you feel idiotic being dumb—and I feel dumb about that marriage. I think it was foolish and pathetic of me to have thought it could have worked."

In retrospect, of course, she has briskly dispensed with any regrets. "I'm not a person who regrets things," she says. "I have this appalling ability to say, 'Well, if I hadn't done this, then that wouldn't have happened, so it's a good thing this happened after all.' There would be no way, in my sane mind, that I wouldn't regret having married Carl, except for the children, who are so cosmically wonderful that I'm thrilled I married Carl. " Nor is she sorry for having written Heartburn, although many of her detractors have hopefully suggested that with the passage of time she might repent. "I don't regret it at all," she says, her voice steely. "I'm extremely fond of it. Given what the actual experience was like, I thought I had written a very goodhumored book about it."

Ephron's control—over everything from herself and her work down to the minutiae of domestic life—is so impressive that one is often tempted to assume she is truly invulnerable. "On the surface, and three levels below the surface, down to the sub-basement, Nora is a very tough person," says Richard Cohen. "But the confidence doesn't quite go down to the toes. She gets scared and insecure and has all those other feelings everyone else has, too." Still, it is a shock when Nora and I do start talking about how it felt to discover, while seven months pregnant, that her husband was in love with another woman, and suddenly her hands fly up to her face, which has turned in an instant from its usual paleness to a blotchy red, and her eyes brim with tears. She clamps a hand to her mouth, and I realize that her lips are quivering so that she can't control them. Her eyes are wide with surprise, as no doubt are mine. We stare at each other for several very long moments, and then she waves her other hand frantically in front of her face as if to shoo something away. "You see, I can't talk about it," she says in a strangled voice. "Even after all these years, I just can't."

It was Christmas of 1979, and Max Bernstein—bom two months premature—was in the neonatal intensivecare unit at Mount Sinai Hospital. For weeks he had lain there in his isolette while Ephron recuperated from her emergency cesarean section and began the much longer process of recovering from the cataclysmic end of her marriage. "Nora went into a period of hibernation, and then one day she called up and said, 'It's time for me to show my face,' " recalls Amanda Urban, whose husband, the writer Ken Auletta, is also one of Ephron's close friends. "The three of us went to Elaine's for dinner, and people were happy to see Nora, and we all stayed pretty late, and then she turned to us and said, 'Do you want to see Max?' So we went up to Mount Sinai in the middle of the night, and there was nobody around; we just walked right up to the intensive-care unit. And there were Christmas lights twinkling on and off, and a big sign that said MERRY CHRISTMAS, and everything was dark and quiet except for all these Christmas lights. Nora put on a gown and mask and went into the intensive-care unit, and she held up to the window this little tiny, tiny baby, and we looked at him, and we looked at each other, and we all burst into tears."

Nora may have been shattered, but she didn't waste much time on her grief; so quickly her friends couldn't believe it, she had found an enviable place to live, set up a new household, and landed enough work to bring in some serious money. Within the next year she had begun to write not only Heartburn but also the screenplay for Silkwood, the Mike Nichols movie about the mysterious death of a plutonium-plant worker who would ultimately be played by Meryl Streep. "Nora had just split up with Carl, and she had these two tiny babies, but she had it all under control even then," says Alice Arlen, Ephron's collaborator on the screenplay. "She just had to make things work out."

Both Arlen and Ephron were essentially novices in the movie business, but over the next few years Arlen watched in amazement as her partner steadily outpaced her. "I just couldn't get over it," she says. "We'd go into things at the same time, and then all of a sudden she really would know— about marketing, about advertising, about the business side. She was learning the whole time, in a way that people would take her seriously. She's a good reporter; she watches, she listens, and she learns. Nora has a tremendous capacity for a lot of work, and she can get a huge amount done in a short period of time. She's got a computer in her brain." The two of them wrote four screenplays together, two of which— Silkwood and Cookie—were produced. But Nora did Heartburn alone, and then When Harry Met Sally. . ., which was a big hit—and all of a sudden she was a director. "I'm out on my own now," Arlen says wistfully. "It wasn't so easy at first. I felt a little bit like a shuttle set adrift, but Nora's really made the cut. She's a director now. I have to get used to it. It's the big boss." She laughs mirthlessly. "Trying to catch up with Nora—that's my goal."

That, as Nora's sisters could tell her, is hard to do. "She was the inheritor, in the strongest sense, of my mother's dreams," says Delia Ephron. "She was given dreams and ambition—to be a successful woman, a successful person, a successful writer. And when Nora decides she wants to do something, she just goes for it. When she started directing, she said, 'Why don't people ever say how much fun this is?' She really enjoyed it."

Ephron's friends attribute this in large part to her incorrigible bossiness. "Had she not gone into writing, she probably would be dictator of Argentina," says Richard Cohen. Ephron simply loves telling other people what to do and how to do it. "If you don't know what to serve for dinner, call me, because I do," she says. "If you don't know where to get $100 worth of flowers for $40, I know where to do this. I am full of information that's just dying to have a place to rest. I know who the cheapest floor guy in New York is who will still do a good job, and my slipcover person is the greatest slipcover person in America. All over New York are slipcovers that would not exist except for me, and I get such pleasure out of them. Where does my need to control all aspects of my friends' lives at all times come from? I don't know, but now that I'm a director, with every hope of making another movie at some point in my life, I have an appropriate channel for it. When you're the director, everyone wants a piece of you; they want to know what you think of the tablecloth. I loved nothing more than being asked 10,000 questions in one day."

"I think in some way my writing that book was a certain kind of male nightmare come true," Ephron says of Heartburn.

For the most part, Ephron's intimates experience her guidance as nurturing; although they love to make jokes about it, they find her a valuable source of information and an unfailing support. "It's very reassuring to know that Nora's on your case, because she's usually right," says Quinn. "She advises me about my career, my household help, the contents of my refrigerator, which are never up to her standards. She gets very upset when things don't go well and she hasn't been consulted, whether it's about a party or a romance. She always gives you good advice, and if you don't take it, when things go wrong she says, 'I told you so.' " Ephron's influence over her friends can extend to the smallest details. "I've taken on all of Nora's affectations, like bringing your own tea bags," Lynda Obst groans. "I'm such a low-rent clone."

Of course, for a true control freak, being a screenwriter is the ultimate torture. "It's one of the real shocks when you're the writer of a movie and you discover that even on a good movie it isn't remotely what you meant," Ephron says. "Every single decision—what they're wearing, where they're sitting, what the room looks like, what the light is like outside. If you could make every movie with good directors, you wouldn't necessarily feel you had to become a director, but you make movies with directors who get so much less out of the script that you think, Well, I could have screwed this up as well as they could have. One of the great joys of directing it yourself is that it may not be good, but it's what you meant."

Long before the first day of shooting on This Is My Life, Ephron had done an exhaustive amount of homework, like the good student she has always been. "I have all these friends who are directors—Mike Nichols, Rob Reiner, Marshall Brickman, Alan Pakula, Sidney Lumet—and they all read the script and gave me advice and notes," she says, as casually as if it were unremarkable to have access to such counsel. She prepared herself so well that she was firmly in control from the outset. "Most of the crew in Toronto was male, but there was no rolling of the eyes," says Julie Kavner. "Nora is so damn smart that it was never even an issue. You don't fuck around with Nora."

For her part, Ephron was even happier than she had expected to be. "When people tell you about directing, they primarily tell you about the sleepless nights and your health going down the tubes and the anxiety and the nightmare of it," she says, her eyes gleaming with satisfaction. "What they don't tell you is that it's unquestionably the best job in the world."

When Pileggi talks about his wife, he gets a smile of pleasure on his face that's so broad he seems about to levitate. It makes Ephron a bit uneasy to talk about how happy she is; after all, she thought her marriage to Bernstein was all right until he delivered his bombshell. If Pileggi sends her extravagant bouquets of flowers with a frequency that dazzles her friends, there is still a part of her that is afraid to believe her own good fortune. Not so her husband. He had known Nora for nearly fifteen years before they got involved, and although he was married to his first wife for most of that time, friends say he always had a soft spot for Nora. Indeed, when they both worked at New York magazine during the early 1970s, one issue featured a cover story by Nick and a cover line advertising another story by Nora; when I express interest, he jumps up, rummages around his office, and— amazingly—manages within moments to produce the carefully preserved eighteen-year-old issue, holding it aloft like a prized trophy. There they are: Nick and Nora, joined in type long before they were joined in life, their high-profile union evoking an appropriately cinematic reference to the glamorous couple in The Thin Man.

Pileggi's first wife left him the same year Carl and Nora went down in flames, and for the next couple of years he was somewhat shell-shocked. "I think Nick was the walking wounded for a long time," says Urban. "But Nora was eviscerated the way Nick was, so by the time they found each other, the notion of finding kindliness had become paramount. There was this unspoken agreement that they weren't going to kill each other. It really does come down to just day-to-day goodness to each other."

For Pileggi, his first dinner date with Nora obliterated old sorrows. "After that I never had dinner with anybody else," he says. "By the third date I had no questions. She's like the kind of Italian mama I grew up with; they make a house really a home. She loves to cook, she's a great mother, she's so smart and talented and inventive and helpful and caring—I've always thought she was sensational."

Pileggi, who has no children of his own but who dotes on his stepsons, attributes much of his professional success in recent years to his personal happiness. "I feel like my work, over the last nine years, has just taken off, as has Nora's, and I think a lot of it is because the home base is covered," he says. "You don't have to date anymore; you don't have to worry about New Year's Eve. All of a sudden our home life was solid and you didn't think in terms of limits; you thought in terms of what you wanted to do."

Mutual friends suspect that professional rivalries played a role in the demise of both of Ephron's previous marriages. When she was married to Dan Greenburg, one magazine interested in competing couples wanted to do a story about the fact that Ephron's writing career was taking off while her husband's was faltering (she refused to cooperate).

While she and Carl Bernstein were together, Nora was her usual machinelike self; she has always been able to chum out copy with a baby or two crawling around at her feet banging on pots and pans. "But Carl was having the most incredible trouble writing, which was pretty much what was wrong with that marriage, and I think it was hard for him being married to somebody who just gets the job done," says Alice Trillin, an educational-television producer who is friends with both of them.

Ephron's third husband doesn't seem to have any problem with his wife's achievements. "We're in similar businesses, but we cover different turf," says Pileggi, who is currently writing a book on the casino business as well as working on two movie projects with Scorsese and another with Paul Schrader. Nor does Ephron's recent promotion to director give her husband pause. "It's such a kick to me," he says, beaming. "I love it." Perhaps fortunately, he harbors no such aspirations himself. He got so restless hanging around the set of GoodFellas that he asked Scorsese if he could be excused. "To sit around watching them move lighting equipment was boring to me," Pileggi says. "Not to Nora; Nora loved it. Nora really wanted to be part of that world, and she's a happier person because she's doing all this stuff."

When Nora's friends talk about how much she's mellowed in the last few years, which they do, they usually attribute it to her happiness in her current marriage. "She finally met this real grown-up, a wonderful person, and I think he's brought out what is more wonderful in Nora," says Liz Smith. "I think with the children and Nick she didn't feel she had to use her elbows so much." Amy Ephron adds, "Nick is very, very secure and he's very easygoing, and Nora's become more easygoing as a result of being with him." Alice Trillin sums it up: "Nora's finally got somebody who's strong enough to be married to her."

At last Ephron has a man she feels she can depend on. "She was very concerned about going up to Canada and being separated from her kids while she was making this movie," says Judy Corman, an old friend. "Nick was this rock: 'I'll be here, I'll come up as much as you need me to, I'll stay away as much as you need me to, I'll be there for the kids.' He's perfect." Pileggi is also sensitive to the difference between his role and that of Bernstein: ' 'Their father is a very important part of their lives," he says.

Ephron seems to have it all these days. "I love my children, I love my husband, I love my apartment, I love my profession, I love my friends—I love my life," she says. Her many blessings notwithstanding, however, some of those who have known her best doubt she will ever be truly content. "She's a very hungry woman," says one friend from way back, "hungry for all the things her parents had—ability, power, the right friends. Nora never has what she wants; Nora will never have what she wants. Nora always wants more."

And demands it: "She's terrible if she doesn't get the right table, ' ' says the owner of a hot restaurant Ephron likes to frequent. Still, the important things are all in place—and now she's even earned a membership in that very small club called women directors. Ephron's fee for screenplays is currently "in the high six figures," and she and Delia have already completed their next script, a comedy about a group of people at a suicide hot line on Christmas Eve, which Nora hopes to direct. Contemplating what more there might be to aspire to, I ask her if she has Academy Award fantasies. She laughs.

"There's no screenwriter who doesn't sit there at the typewriter or whatever thanking his dry cleaner or whoever was instrumental in getting the movie made," Ephron says. "I swear to you, the person who did Debbie Does Dallas had a fantasy. My fantasies about winning the Academy Award have been largely focused on screenwriting so far; I'm not quite deluded enough to have fantasies about winning an Academy Award for directing." There is a pause. "But I will," she says. "I guarantee you I will."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now