Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowTHE BOOK OF DAVID

After a Pulitzer and a shelf of best-sellers, David Halberstam has gone back to his first, perhaps best story for his next big book: the young heroes of America's civil-rights crusade

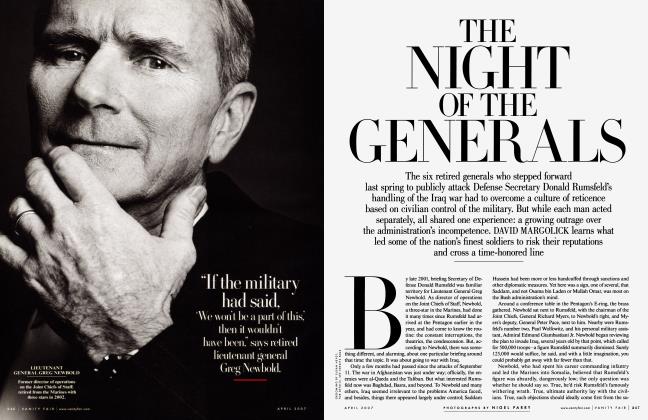

DAVID MARGOLICK

Books

It was the spring of 1985, and 25 years had passed since a group of polite young black men and women faced jeering mobs, hostile policemen, a resentful business community, craven officialdom, and centuries of entrenched southern racism in order to integrate the lunch counters of Nashville, Tennessee. Gathering to mark the anniversary, the onetime protesters,

now middle-aged, invited someone who, while technically not one of them, had been a crucial part of their crusade. He was David Halberstam, who had, as a young reporter for The Nashville Tennessean, chronicled those epochal days.

Halberstam had long since become one of America's most prominent journalists. He'd covered wars in the Congo and Vietnam for The New York Times, won a Pulitzer Prize, and written several

important books, including The Best and the Brightest and The Powers That Be. But when he returned to Nashville he came to realize that it was perhaps his best story: where the first mass sit-ins and arrests of the civil-rights era had occurred; where the Gandhian culture of nonviolent protest took root most deeply; where a whole new generation of black leaders had been spawned.

"I was just enormously moved," Halberstam said of the return visit. "What I felt was a sense of change in the city, much of it good, a sense that in this little group, at least, we had gotten somewhat beyond black and white, that something had worked. It was an important part of my life that I hadn't talked about or written about, and suddenly it was beginning to come out of the closet."

Indeed, as far afield as Halberstam the historian had foraged for book topics—America's press empires in The Powers That Be, the American and Japanese auto industries in The Reckoning— he came to see that he had a great book in his own background. It is the story Halberstam tells in his latest book, The Children, to be published this month by Random House.

To Halberstam, the book fills a hole in civil-rights historiography, which has focused more on the mountaintop than on the grass roots. "Most of the books about that period tend to be about Martin Luther King, who is self-evidently a great man, a great leader," he said, sitting by the cappuccino-maker in the kitchen of his apartment on Manhattan's Upper West Side. "But it's a little bit like writing about World War II and only writing about Dwight Eisenhower or Winston Churchill."

Working on the book also filled a gap in Halberstam's understanding of the men and women he'd covered and come to know. He'd forsaken Nashville and the civil-rights movement in late 1960 for The New York Times and Africa and Southeast Asia. But these foot soldiers went on to become battalion leaders and company commanders as the civil-rights movement moved from Nashville to the Deep South. As Freedom Riders and marchers from Selma to Montgomery, they led protests that prompted a chastened nation to enact the landmark civilrights legislation of the mid-1960s.

"These days there's all too much coverage of pseudo-events about extraordinarily inauthentic people doing inauthentic things," he said. "What I wanted to do here was to recall this remarkable moment when a group of seemingly ordinary young people, acting largely upon their religious faith, again and again risked their lives over a five-year period to dramatically change this country."

Listen to the people who walked that historic walk and they'll tell you that Halberstam, then 25 years old, was really one of them. By marching alongside them rather than watching them from across the street, and by telling their story straight when they were too embattled to tell it themselves, he became a vital part of their cause. "He was an intense, compassionate, empathetic young reporter," said Dr. Rodney Powell, one of those profiled in the book. "All of us began to trust David. We shared our thoughts, our feelings, our strategies with him, and this helped him gain real insight into what the movement was abouHt and what motivated us."

lie did so at considerable danger to H himself. "To be white with a pencil 11 and a pad in the South in those days was very dangerous," said John Lewis, another protest leader, now a congressman from Atlanta. "The people who attacked us didn't want the story to get out. If it hadn't been for David Halberstam, the movement in Nashville would have been like a bird without wings." (Mr. Lewis is not the only public official to emerge from the protests; another former marcher portrayed in the book is the embattled mayor of Washington, D.C., Marion Barry. "He was this rather sweet, charming young man—a bit of a clotheshorse," Halberstam recalled.)

Now 63, Halberstam still seems entirely too youthful to have bronze plaques commemorating events he once covered. He is already working on his next book (about the Chicago Bulls and Michael Jordan) and is contemplating several more. "I'd like to do what I'm doing for at least another 10 or 12 more years," he said. Yet he has grown old enough to start taking stock of a career forged from what he called "shrewd choices, good luck, good instincts, and a very good era."

In 1955, when Halberstam contemplated life after serving as managing editor of The Harvard Crimson, the traditional options were clear: to be a gofer at a prestigious daily newspaper or take a fancy fellowship abroad.

He saw another route.

The impact of Brown v.

Board of Education, the 1954 Supreme Court ruling outlawing segregated schools, was about to convulse the South.

Not only was this where the news would be, it was where Halberstam, a tall, scrawny kid unsure of himself and his journalistic talents, could pick up what he felt he lacked: tenacity, a knack for people, and, most of all, courage. "It was very important to me to learn physical courage, and covering the South, particularly if you were Jewish, was always a little edgier, because everybody knew that it was 'the niggers and the Jews' who were doing all this awful stuff," he said.

Halberstam loaded up his 1946 Chevy with most of his possessions—a single suitcase of clothes, a primitive hi-fi, an LP of Louis Armstrong doing W. C. Handy—and headed to Mississippi. He began in West Point, population 8,000, reporting by day for the Daily Times Leader, reading Gunnar Myrdal's classic 1944 study of race relations, An American Dilemma, by night. Within 10 months he'd been fired, in part for pursuing stories about integration, one of which involved a young man named Medgar Evers, who was then the NAACP's field secretary in Mississippi. A friend then got him the job on the Tennessean. To Halberstam and people like him, it was a beacon of liberalism in the Jim Crow South. To its detractors, angry that it had resolved to highlight the nascent civil-rights movement rather than bury it on its inside pages, it was simply "the nigger-lover paper."

With a great newspaper behind him, Halberstam found what he was looking for. "When I was on my own, I was a world-class coward," he said. "But when

"To be white with a pencil and a pad in the South in those days was very dangerous."

I represented The Nashville Tennessean I was absolutely fearless." His courage was fortified by some of the stories he covered, such as the 1960 campaign of Estes Kefauver, the state's senior senator, who all but forced those who loathed him for supporting civil rights to look him in the eye and shake his hand. (He won anyway.) "It's one of the great things I ever saw as a young man," Halberstam said.

Halberstam had been in Nashville four years when, in February 1960, the protesters left their universities and churches and descended upon the segregated lunch counters at Woolworth's and other dime stores. When they were torn off the stools by angry whites who ground out their cigarettes in their hair or poured hot coffee down their backs, Halberstam was there, taking it all down.

"A sympathetic referee" is how John Lewis described him. "A friendly shadow," said Bernard LaFayette, another marcher, now president of the American Baptist College in Nashville. And by ducking the same bricks, giving them wise counsel, and occasionally even offering them protection—Curtis Murphy, now an assistant high-school principal in Chicago, recalled the time Halberstam shielded a young white protester as she fled her attackers—he became one of them.

"We told him that he should be included in the book, that he's one of the most important people," said Dr. Gloria Johnson-Powell, now a professor of child psychiatry at Harvard Medical School. "He was not a bystander in any way, although he will not acknowledge that." (That, incidentally, was how the competition viewed things, too. "If we wanted to know where the next sitin was going to be, we would just call David," said Larry Brinton of the Nashville Banner, whose paper all but banned coverage of the protests.)

To Halberstam the experience proved how constructive journalism could be, or once was. The articles he later wrote in Vietnam for The New York Times may have outraged President Kennedy, but rarely could he feel their impact; he was too far away. In Nashville he felt it every day, as the community simultaneously teetered on the brink of chaos and evolved.

Will Campbell, who was in Nashville at the time with the National Council of Churches, said that what surprised him most about The Children was its religious undertone. It shouldn't have, he said, because Halberstam once told him he comes from a long line of rabbis.

Unlike many of the Christian clergymen in Nashville then, he said, Halberstam "saw this whole movement as a theological movement and not as a secular, legalistic movement. There's not the fire in his eyes as there would be with a Jeremiah or an Amos, but in a journalistic fashion, he's saying that the children are saying 'thus saith the Lord.'"

Karl Fleming, who witnessed much of what Halberstam did while covering the civil-rights movement for Newsweek, called The Children Halberstam's finest work. "He was highly offended by the Vietnam War, but I think this is really where his heart is, and was," he said. "These are the events that shaped our early lives; these are the things that made us as reporters and as human beings. There's more humanity in this book than in anything he's done."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now