Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe brilliantly superficial Sex and the City series ended romance as we knew it. Which is fine

August 2018 Sonia Saraiya Michelle ThompsonThe brilliantly superficial Sex and the City series ended romance as we knew it. Which is fine

August 2018 Sonia Saraiya Michelle ThompsonSex and the City, which debuted 20 years ago this summer, was not simply a TV series. It was a phenomenon—a comedy, a fashion bible, a trend report, a manual to New York, a lifestyle manifesto. Its success, and its cultural footprint, can be attributed to several factors that amounted to a perfect storm: frank and provocative subject matter, ultra-contemporary fad-spotting, and an arch, old-fashioned tone that sometimes laughed with its sexually adventurous characters but more often laughed at them. Sex and the City had no compunctions about being wish fulfillment; if anything, it reveled in the implausibility of its own world, where a practically freelance sex columnist regularly wore $400 shoes and a gallerina intent on nabbing a husband wouldn't deign to give blow jobs. The stylish and upscale leads were only occasionally tethered to the rules of the rest of society—usually through the self-reflective voice-over of lead Carrie Bradshaw (Sarah Jessica Parker), who asked questions like "Are we sluts?" as she pined for a longer-lasting romance than the zipless fucks that made up most of the series's adventures.

But despite Carrie's rumination, Sex and the City was never an angsty, gritty, or even especially thoughtful show. Every time the series uncovered remarkable complexity at the root of its fun, it found twice as many opportunities to mate its untethered girls the butt of its humor. It eventually admitted the financial limitations of some of its characters, most famously in the episode where Charlotte (Kristin Davis) helps Carrie make a down payment to buy her apartment. But class privilege is just the tip of the iceberg; in its six years on the air, the show barely acknowledged the overwhelming whiteness and straightness of its cast, and when it did, the results were usually disastrous. (The series wouldn't even kowtow to the reality of the weather: for four years, Sex and the City never depicted a season other than spring.)

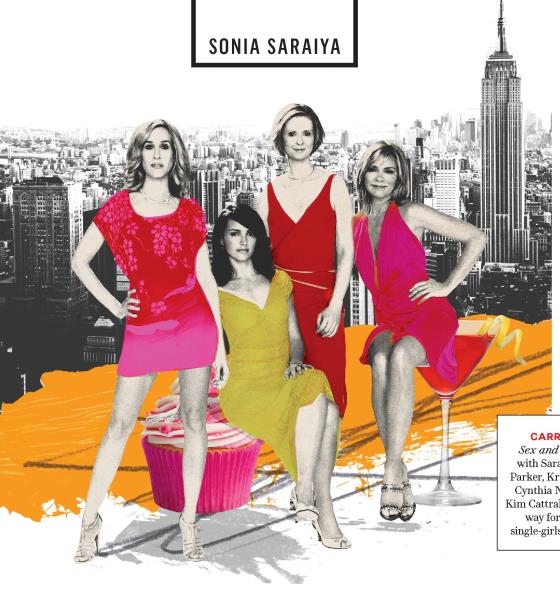

CARRIE ON Sex and the City, with Sarah Jessica Parker, Kristin Davis, Cynthia Nixon, and Kim Cattrall, paved the way for today's single-girls subgenre.

CARRIE ON Sex and the City, with Sarah Jessica Parker, Kristin Davis, Cynthia Nixon, and Kim Cattrall, paved the way for today's single-girls subgenre.

In the two decades since, the single girls of the post-Sex and the City small screen care less about style and more about substance than those in creator Darren Star's frothy, superficial world. They're poorer, messier, less white, and less straight, from Insecure's Issa (Issa Rae) to 30 Rock's Liz Lemon (Tina Ley), The Mindy Project's Mindy Lahiri (Mindy Kaling), Broad City's Ilana and Abbi (liana Glazer, Abbi Jacobson), Fleabag's unnamed lead (Phoebe Waller-Bridge), and, of course, the girls of Girls—less than a decade removed from the New York of Sex and the City yet apparently light-years away.

The obvious limitations of its fantasies, though, are part of what made and make Sex and the City so endlessly engrossing. More than once, the show ridicules its leads for expecting the rest of the world to work the way that their New York does. Even so, the series presented an unfettered fantasy of desire. It was a manual for living shamelessly, in the best sense of the word; no wonder the show had complete disinterest in even the pose of being woke (or whatever the equivalent term was in 1998). Deep down, it didn't really care about anything except living out the fantasies of modern life in the 90s and early aughts—sex, dating, New York's hottest clubs, and expensive things, which all together made for a years-long secondary story told entirely through wardrobes, workout classes, and impulse vacations.

Sex and the City's world, right to the end, was a flight of fancy. But its legacy points away from that and toward a post-romantic comedy world, where fantasies have to succumb to everyday realities. Girls, which succeeded Sex and the City on HBO and in some ways supplanted it, presented a similarly bleak romantic playing field in Lena Dunham's version of New York City—but one studded with much more angst. And Insecure, the third link in the HBO "single girls in the city" chain, ended its second season with its protagonist going broke, after her attempts to live out her dreams were met with the cold realities of her finances. Where Sex and the City skated through everything with a laugh and a trilled "Fabulous!," the shows that followed have found a way to examine and redefine what it might mean for a girl to have it all—or, at the very least, to find a happy ending.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now