Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

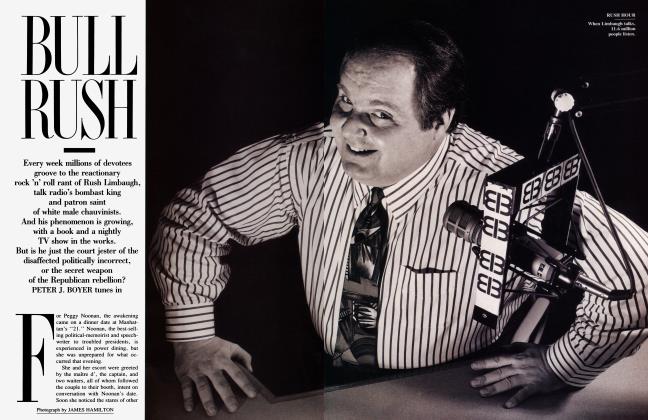

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowNow that "Nick the Knife" Nicholas has been sacked, can Jerry Levin really and save the Time ailing Warner? Steve Ross

MAY 1992 Richard M. ClurmanNow that "Nick the Knife" Nicholas has been sacked, can Jerry Levin really and save the Time ailing Warner? Steve Ross

MAY 1992 Richard M. ClurmanAs noon approached one day in early March, Nicholas J. Nicholas Jr., a taut fifty-two, angrily paced his spacious Rockefeller Center office, a colorful de Kooning shining from its polished cherry-wood walls. Nicholas was enraged, yelling at visitors and barking into the phone. Just a few days earlier, in a secret struggle for power, he had been brutally ousted as president and co-chief executive officer of Time Warner, the world's largest media-and-entertainment conglomerate. It came as a career-killing blow to him, the sudden end of a lifelong dream. But there was nothing he could do about it: the man who had been known at Time Inc. for years as ''Nick the Knife" finally had the knife turned on him.

When Time Inc. and Warner Communications merged two years ago, he thought he had an ironclad contract, backed by an oath "signed in blood" from Warner's persuasive, ingratiating chairman, Steven J. Ross. Both documents provided that Nicholas would be an equal partner with Ross and then succeed him in 1994 as boss of the multibillion-dollar company. Instead, Nicholas was forced out, with only one day's notice, by the company's twenty-three-member board of directors, with only one dissenting vote. Then the board unanimously voted to replace him with his old Time Inc. rival, Gerald M. Levin, also fifty-two.

I phoned Nicholas in his office. Could we talk? Nicholas's answer was polite but brisk and conclusive. "Nope. Nothing. I've decided that whenever I tell whatever I have on my mind I know who I'm going to tell and it ain't you."

His answer was chilly for good reason. The week before, I had published a book (To the End of Time: The Seduction and Conquest of a Media Empire) whose reporting predicted his downfall—based on painful accounts from colleagues of his abrasive executive style and on his own self-incriminating words. Why in the world should he agree to talk to me?

But—mirabile dictu—he did. Three hours later, I picked up my ringing phone to hear a hot, impulsive Nicholas. With little preface, rage rising in his monologue, he said portentously, "What's on my mind is that I know a lot, as you might surmise. Not only why what happened and when it did and the way it did, but I also know a lot of other things. What I'm going to do is eventually find someone to tell the story. I have a journalist in mind [Connie Bruck of The New Yorker], It certainly won't be you. I have kept my mouth shut at the moment for a lot of reasons. Nobody has asked me to, but I have decided as a matter of personal conviction not to get into a pissing contest with this great spin bullshit they're putting out. I'm not talking to anybody for now. The sleaziness of the whole thing! I don't want to be associated with it until it is clear how sleazy it is. Nobody is onto this thing yet." Good-bye.

What was he talking about? In the corporate headquarters, the Time Warner Building, and half a block away in the Time & Life Building, as well as on the board's telephone grapevine, there were whispered reports tarring him. They said Nicholas was railing loudly behind the closed doors of the office he still occupied that there had been plots against him from the very beginning. Incredibly, they claimed that, among other nightmares he ranted about, Nicholas was saying that for all he knew Ross may have been in cahoots all along with Paramount's Martin Davis, whose unwanted hostile bid had forced Time to buy Warner for$14 billion, yielding Ross many millions more than he would have received in the original deal. ("Someone must be kidding," says Davis. "That theory would be sick.") There were additional reports that Nicholas was fulminating about all kinds of other malign "conspiracies."

In fact, Time Warner insiders admit his ouster was a conspiracy. But its makings were not of the kind he darkly hinted at. Nicholas, they say, did himself in.

As the date of his ascension got closer, the sharply focused onetime financial whiz kid seemed to be racing to his goal, stopwatch and calculator in hand, knocking over every barrier. When there were disagreements with Ross and others, Nicholas could get downright disagreeable and explosive.

Even secretaries in the office and other staff couldn't stand his turf wars or his abrupt manner. If press handouts didn't give Nicholas's partnership enough credit, he bitched. Magazine articles that failed to mention his name made him sulk. "To the world outside," a Time Warner director explained, "Ross is such a star that it's still kind of 'Nick who?' "

The tension on top was so great that as long ago as late last fall Ross and Nicholas stopped communicating. When Ross had to take leave of the office to be treated for prostate cancer in November, intermediaries were confused by conflicting orders. Insiders say the ambitious Nicholas began acting like Alexander Haig when he announced on network television after the Reagan assassination attempt, "I am in control here." Many thought Nicholas—like Haig—was out of control.

In fact, Nicholas's clashes with Ross were preordained almost from the day they came together in their warm, temporary embrace. Consider a description of the two from a friend of both, a senior member of the Time Warner board:

Ross. "He's 'the Great Schmooze.' An enormously effective personal salesman. Enormous! I've watched him in all kinds of situations. He has a warmth about him and a disarming, self-deprecating manner that's almost hypnotic. Eighty-five percent of it is real. Of course, we all have a little phoniness in us, and I'm not sure what Steve is really like when the doors are closed and he's by himself. But he has a wonderful style, a good listener, very diplomatic, sensitive. Steve has a tendency to talk you to death. One of his strategies of carrying the day is to exhaust you. He is not combative, just tenacious. Even though he wouldn't scream and holler at you, he doesn't let go."

Nicholas. "Nick is very tightly wound, intense, sometimes too intense, sometimes almost obsessed with his viewpoint. He's a better talker than a listener, sometimes too confident, too cocky, too self-assured. He has all the smarts. But I sometimes get a little concerned with his humanity. There's always been a dark side to Nick. He doesn't easily accept the fact that there are other bright people around. Nick tries to do everything himself, so he hasn't got time to be really nice to people. He's not as bad as he sometimes projects himself to be, but at times his ambition and his intensity get in his way."

Could there be a more incompatible couple?

"I'm supposed to be the ice-water-in-the-veins guy," Nicholas said. "What am I going to do? Go around and deny it?"

Nicholas himself had diagnosed his potential problem long before his downfall. "I'm supposed to be the ice-water-in-the-veins guy," he said a year ago. "What am I going to do? Go around and deny it? I'm the ultimate realist. I don't think I'm the slightest bit mean.

"Not many people know me well," he added. "I've been self-reliant my whole life. I don't think people get me wrong because they know me. They get me wrong because they don't know me."

Nick Nicholas, the son of a Greek-born World War II hero who was a U.S. submarine captain, had been brought up as a hardworking navy brat. But on scholarships and loans he attended all the "right" schools: prepped at Andover, graduated from Princeton, earned an M.B.A. at Harvard, where he was spotted by a Time Inc. recruiter and hired as a lowly numbers man in the controller's office.

A shrewd analyst and planner, he artfully made his way up the Time ladder. He became assistant to the company president, and shone in Time's fledgling cable operation. He did so well that his mentor, Time Inc. chairman J. Richard Munro, made him chief financial officer of the whole company, and finally its president. Though Nicholas's climb had taken twenty-one years, he had maneuvered from job to job with swift self-assurance. He liked to quote Mel Brooks's 2,000-Year-Old Man, who, when asked his main means of locomotion, replies, "Fear. If you don't move quickly enough you get eaten."

Like his submariner father, Nicholas had always finely navigated his own career, leaving some bleeding casualties in his wake. One was his competitor for the top spot, Jerry Levin (pronounced like "begin"). When Nicholas was finally named president of Time Inc., in 1986, he saw to it that Levin, then an executive vice president, was thrown off the company's board. (After two years, Levin was restored to the board as vice-chairman, but by then Nicholas was in command.) Nicholas later shrugged off the power play: "There was a period of estrangement. Jerry had some brilliant ideas, but with no foundation under them to make them happen. That's not even an issue anymore because he's terrific with people and he's much better at running things today. The caricature of me is that I'm a great operator and a lousy dreamer. The truth is I'm a hell of a dreamer and a damned good operator and so is he."

"At the time, Nick had a fairly mechanistic way of looking at the world," Levin recalled with barely concealed resentment. "I think Nick acted too quickly. Nick liked and wanted the exercise of power. Those things are fundamentally inimical to me. I'm not— Nick had a different set of characteristics."

Different indeed. As one friend of both put it, "Nick is as opposite in outlook from Jerry as Thomas Hobbes ["The life of man. . .nasty, brutish, and short"] was from Socrates ["The unexamined life is not worth living"]."

The son of devout Russian-Romanian immigrant parents, Levin, whose father sold groceries, aspired to be a rabbi. A philosophy and literature student at Haverford College, he changed his mind and instead went on to earn an LL.B. from the University of Pennsylvania Law School. At a white-shoe Wall Street law firm, he worked on big civil-rights and First Amendment cases under eminent advocate Whitney North Seymour Sr. He was recruited by the superplanner David Lilienthal, once chairman of the New Deal's Tennessee Valley Authority and later of the Atomic Energy Commission, who sent him off to work on massive irrigation and electrification projects in Iran. When he returned in 1972, he joined Time's struggling, infant cable operation. He became HBO's visionary, transforming it into the biggest pay-TV cable network by blanketing the U.S. with satellite-borne signals.

"There's no one in the world I love more than Jerry," says former Time chairman Dick Munro. "He's like a son to me. He's the most irreverent son of a bitch I've ever met." Nonetheless, Munro passed him over in favor of Nicholas, fearing Levin had neither the financial experience nor the executive toughness to run the company.

Though he was exiled to the backwater of "strategic planning" when Nicholas took over, Levin ended up rescuing the company's "transforming transaction," the Time Warner merger. After the complex deal had collapsed, he glued the intricate pieces back together and shepherded the merger to its rocky conclusion.

Ironically, in Time's long quest through the 1980s to form a partnership with another company, every potential deal had foundered on the nonnegotiable demand that Nicholas had to be the C.E.O. of the new company, to carry on "the Time Inc. tradition." When the merger possibility with Steve Ross and Warner appeared, it too crashed for the same reason. When Ross ultimately agreed, Munro, the Time board, and Nicholas himself thought they had sealed it with an elaborate fifteen-year contract that described the succession process by date and number. Incredibly, what not one of them—except Levin— realized until long after the deal was completed was that in the fine print of the complex merger agreement they had missed the point. What they had signed was only a money contract, not a guarantee of Nicholas's succession. As one Time director described the belated discovery, "Nick will inherit the job. But he won't if he doesn't earn it."

From the day Levin's dream offspring, Time Warner, was delivered, January 10, 1990, it was treated like an unwanted bastard. The stock of the combined company plummeted to half Time Inc.'s pre-marital value; front-page headlines of the world press shouted, ANOTHER FIASCO AT TIME WARNER, and TIME STUMBLES; and even inside the company the combination was despised ("a marriage made in hell"). The new company, hobbled by an $11.5 billion debt as a result of the merger, just couldn't do anything right. When its own Fortune listed the three hundred most admired companies in the U.S., Time had nosedived from a radiant 6th place in 1984 to a humiliating postmerger 242nd.

Nicholas cut out, refusing even to attend planning sessions. He isolated himself in his office, bitter at being overruled.

In public, co-C.E.O.'s Steve Ross and Nick Nicholas seemed to start their working relationship with all the finesse of a figure-skating pair in a media Olympics. But Nicholas was already betraying early signs of impatience. When I asked him how Ross was adjusting to working with a full partner for the first time, Nicholas responded with customary hubris: ''He has to adjust. He doesn't have to defer, he has to share. Steve will often say, 'I haven't talked to Nick on this one, but here's what I think.' " When they did talk strategy, Nicholas was more for hunkering down, selling assets if need be; Ross insisted on expanding by taking in new partners.

The personal tension reached its apogee late in the summer of 1991 when Ross again tried to make good on his widely publicized promise to find what he calls, "you should excuse the expression, strategic alliances" to reduce the company's debt. Toshiba and the Japanese trading company C. Itoh offered more than a billion-dollar investment if they could share in some of Time Warner's movie and cable profits. Nicholas had often balked at taking such a "haircut." Minority partners, he had said, "are not going to pay what the assets are worth." Ross wanted to go ahead. Nicholas cut out, refusing even to attend the planning sessions. He isolated himself in his office, bitter at being overruled. Nicholas's opposition to the Japanese deal stalled it for four months, possibly costing the company, Time reported, "an extra $100 million to $200 million" before it closed.

Ross calls himself a dreamer. He relied on his financial metaphysician, Israeli-born Oded "Ed" Aboodi, to translate his dreams into numbers. Levin, who had become Aboodi's soul mate during the merger negotiations, shared a flexible approach to business strategy. Nicholas, structured and didactic, was odd man out. The whirlwind RossAboodi combination didn't require much help from Nicholas, who found Aboodi's presence especially discomforting.

At first Ross tolerated the differences diplomatically, admiring over Nicholas's sulking shoulders the skills of softspoken, passionate Jerry Levin. Ross, said another director, "was a real believer in what Jerry could do for this company." Journalists close to the company began making bets on how long Nicholas would last before Levin came in.

When Ross got sick last November, Nicholas began acting more overbearing. The reality of Nicholas running the company alone— possibly soon—rose like an ugly dawn. If Ross indeed was not to come back as a result of his illness, it seemed inconceivable to many, including old Time directors on the board, that Nicholas would be able to run the company.

Levin himself could no longer imagine playing Don Quixote in a kingdom ruled by Nicholas. Levin's wife had told him that she had always been so proud of him when he worked for Time Inc., but now that it was Time Warner she no longer felt that way. Over Christmas at their Vermont retreat, Levin later told fellow Timeincers, he read the galleys of my book, which reports many harsh criticisms of Time Warner. After he finished reading, he said, he took "a walk in the woods" and decided Time Warner had to be "fixed."

Ross had come to the same conclusion. His wife, Courtney, who had cut short an around-the-world tour to be at her husband's bedside, complained to Levin that Ross's health was not being helped by all the executive tension. Levin visited Ross in his sprawling East Hampton house. Quietly, Ross and Levin decided that Nicholas had to go. Ross, who refuses ever to fire anyone himself, left most of the heavy work of persuading the board of directors to Levin and Arthur Liman, the superstar lawyer who is also Ross's closest confidant and godfather to his daughter. A majority of the befuddled, feckless directors who had come from the Time board were ignorant of the inner workings of the company and easy to turn around. Former Time chairman Dick Munro, who had promoted Nicholas, had on his own reluctantly concluded that Nicholas had changed for the worse in his new role.

By the time Nicholas got word of the coup against him, it was too late. Donald S. Perkins, chairman of the Time Warner board's governance and nominating committee and a onetime stalwart Nicholas advocate, phoned him in Vail, Colorado, where Nicholas was on a skiing holiday with his psychotherapist wife. Fortune later reported that the unflappable Perkins began, "Are you sitting down, Nick?" After he heard he was being forced out, the magazine said, "Nicholas was so shocked and saddened . . .that, when she saw him, his wife, Lynn, thought that a member of the family had died."

Nicholas was invited to argue his case before the board and was offered a plane. He checked his own sources and found that any directors he might have swayed would have been overwhelmingly outvoted by the board's solid wall of Wamerites and disaffected Timeincers. Wisely, he stayed with his family in their snowy Vail bunker.

In theory, Ross presided over the emergency board meeting the next day. Although vice-chairman Martin Payson ran it, Ross was present on a speakerphone. The board, which met for only a little over an hour, was nearly unanimous in its vote to dismiss Nicholas. (Only Henry Luce III, son of Time's co-founder, dissented, urging more due process.) In an uncontested vote, the board installed Levin in Nicholas's place.

The board solemnly agreed, in "deference" to Nicholas's feelings and reputation, to keep their mouths shut about his ouster (which, of course, they failed to do) and give as the official reason 4 ' strategic differences. ' '

The details of Nicholas's financial settlement were not worked out. (Nicholas had requested an office in the Time & Life Building as his Elba. No way, said a horrified Time Warner officer.) In purely financial terms, one option had been written firmly into his existing contract: Nicholas could technically remain an employee of the company for the next twelve years, accumulating as much as $30 to $50 million or more, including his present stock options and annual bonuses, for doing nothing. (This was in addition to the estimated $16 million in stock he owned at the time of the merger.) He had lost only his job, not the rewards that went with it.

When Ross got sick, the reality of Nicholas running the company alone—possibly soon—rose like an ugly dawn.

More likely, he will choose to get on with his life and take the lump-sum payment his contract guarantees, estimated to be worth, with his options, $30 to $35 million (not the $15 million widely reported), in addition to a continuation of all his lavish benefit programs (life and medical insurance, etc.).

One longtime Nicholas friend and associate concluded, "Nick knew the lyrics of Time Inc., but he never really understood the music." On the thirty-fourth floor, where Nicholas once cracked his whip, one of his former subordinates was harsher: "Ding, dong, the witch is dead." Another staffer offered an elegant but equally unsentimental epitaph: "The Iceman Goeth."

Nicholas's sudden removal was greeted almost everywhere with cheers and the self-righteousness of hindsight. Wall Street applauded by jacking up the company's battered stock by close to ten points. From the Polo Lounge of the Beverly Hills Hotel to the tables down at Mortons, Hollywood wise guys happily danced on Nicholas's grave. An overconfident "suit," one of them called him, "an amateur strutting on our turf." (Cynically, they began speculating on how long Levin would last before one of their own was put in. "Levin is very smart," said one lawyer, "but not big enough to lead that company.")

No one clapped louder than the journalists and publishers in the Time & Life Building, headquarters for the company's magazine and book publishing, where Nicholas had honed his cost-cutting reputation. (Reducing costs "isn't going to end," he had recently announced in a menacing tone, explaining the layoff of some six hundred magazine staffers. "It's now part of the way we do business.") Not only had the magazines been reduced to a small wedge of profit in the whole showy entertainment-and cable company, they had been orphaned and left leaderless. Their staffs and budgets had been cut; their morale was at an all-time low. The standard-bearing magazines had been charged with forfeiting their independence, ignoring the activities of their parent company, or running self-serving, censored coverage.

Worse, for the first time in their history the magazines were being ruled by a bottom-line businessman, Reginald K. Brack, a Nicholas protege. Brack dominated the editor in chief, who in the past had always been the most powerful publishing figure. But that exalted throne was now occupied by the almost invisible Jason McManus, whose wavering leadership earned little respect from his managing editors or their staffs.

The journalists felt liberated when they heard that Nicholas's replacement was Jerry Levin. At first glance, Levin may seem an unlikely editorial hero, since he's never worked as a reporter or editor a day in his life. Virtually unknown to the world outside and barely acquainted with most of the journalists at Time Inc., he nonetheless knew every symbolic button to push. One of Levin's calls after the surprise announcement of the coup was on the venerated Andrew Heiskell, chairman of "the old Time | Inc." for twenty years. In the lean-and£ mean late eighties, Heiskell's successors, led by Nicholas, had evicted Heiskell from his retirement office and taken down his company-commissioned oil portrait. Now Levin arrived in Heiskell's tiny rental office to redress the heavy-handed ingratitudes, which had become public knowledge. Too late to restore the portrait to its place of honor, since it had been donated to the New York Public Library (where he had also been chairman). Instead, Levin invited Heiskell to occupy a "nice office in the Time Warner Building." Heiskell agreeably declined the gesture. But overnight, board minutes and budgets, from which Heiskell had been cut off, began coming his way again.

Levin summoned the managing editors of the magazines to the Time magazine conference room —not the executive floor, where they had become accustomed recently to being summoned to receive bad news. Next, in rapid succession, floor by floor, Levin met with the editorial staffs of the magazines and book publishers. Addressing each group quietly, without notes or histrionics, he seemed, said one editor, more like "Woody Allen, pulling on his ear, looking at the floor, than the programmed business guys we usually hear."

Levin, who barely mentioned Nicholas, had not come to replay the plot that had deposed him. Instead, the new company president wanted to discuss the future. It was a new era, Levin declared, or actually the reaffirmation of an old one. The magazines were the "heart and soul" of Time Warner, he said, and they had been badly treated since the merger, demoralized, forced to concern themselves too much with profit margins, budgets, and rates of return. But the cost-cutting and layoffs would not be "a way of life" (as Nicholas had warned). "Those kinds of layoffs died last week," he pledged. He wanted Time Wamerites to bring more love to their work. "By love I don't mean eras but agape," he explained, spiritual not sexual love. "Whoever heard a C.E.O. use the word 'agape'?" exclaimed an editor after a meeting.

In front of the managing editors, he obliquely chastised editor in chief Jason McManus for not being visible enough. He told the stoic McManus he needed to represent the values of the company's journalism, to step forward more assertively and reconsider his "consensus" style management. Instead of resigning because of the polite dressing-down, McManus hopped on the accelerating bandwagon. "I have a new assignment," editors say he announced. "This is a new age. The real beginning of the merger. I find it immensely liberating. I hope you will, too."

As Levin made his rounds, he passed a receptionist on the executive floor, who blurted out, "Thank you, you're making us all feel important again."

Was Levin too good to be true? Were they being conned again, this time by a quiet new cheerleader who had read as many books as they had and spoke their language? None of the notoriously skeptical journalists seemed to think so. "If he was pandering," said one editor, "at least he knew who to pander to."

"When Steve doesn't say someone he works with is the most wonderful person in the world, you know there's trouble."

Most remarkably, Time and Fortune both ran stories about the uproar with all the energetic reporting and candor they could muster. When the Time Warner merger had been announced, Jason McManus had blotted his reputation by preventing Time from reporting the story at all. (Levin alone among the high command had opposed McManus's decision.) Not this round; McManus didn't even see the stories about Nicholas before they were published.

COUP AT THE TOP, proclaimed Time. "Officially," the magazine said, "Nicholas resigned....In fact, he was ousted in a coup conducted, he angrily told friends, in banana-republic fashion." In a story headlined AFTER THE COUP AT TIME WARNER, Fortune sharply raised the question of why the "not-so-independent board" had again been so uninformed about the problems in the Ross-Nicholas relationship and on the magazines. Time's and Fortune's stories were the most honest, critical coverage the magazines had ever been allowed to run about their parent company, "making up for past sins," as one critic observed. ("And we even ran favorable reviews of your book in both magazines," one senior executive proudly pointed out to me.)

There were other, less public signs of the change. Some of the uniquely harsh demands that management had been making in the Newspaper Guild negotiations were immediately dropped. The development of a new magazine (working title: Globe), which had been blocked for months because there was "no money" for it, was suddenly resumed with new funds. Preliminary dummies of the "new, redesigned" Time, due to come out in the late spring, were discreetly unveiled to a wider circle of company alumni. And the consensus was agreeable surprise. The magazine, they concluded, was not heading downstream—as many feared—but was actually more faithful to its news-and-ideas mandate than its showy makeup had made it appear in recent years.

Privately, Levin worried about raising expectations too high. "But he couldn't have started out better," one senior editorial executive said, a sentiment echoed in the halls of the Time & Life Building and its outposts around the world. "It was," said one impressed alumnus, "like the Prague Spring with no Russian tanks even in sight."

Steve Ross, racked by pain, deadened by Percocet, was sitting in a straight-backed armchair in the dark, cavernous living room of his Park Avenue duplex. He was tieless, his hair disheveled, not coiffed the way it has been most days of his meticulously attired life. Over his knees, covering his slippered feet, was a tan camel-hair shawl.

It was on the eve of bleak November, and he had invited me to spend some time with him, to continue our interviews for my book—even though for the last week he had been lying in agony on his bed upstairs, strapped in traction for what he described as an ailing back. I had explained in advance that I didn't want to intrude on his discomfort, but Ross had insisted.

Unfailingly polite, he half struggled to rise from his chair as I walked in. While still standing, I again urged that the interview was unnecessary and that he should go back to bed. "No," he said, squirming, "this probably takes my mind off my back. Up there it's all I can think about. This is a welcome distraction. Make yourself comfortable on the couch."

Then he explained that some years ago he had had a disk removed to cure a bad back. Now the pain had returned. A butler appeared, surprisingly dressed in a double-breasted blue pin-striped suit, like a gofer out of The Godfather. He deposited a silver tray with coffee, grapes, cheeses, and crackers alongside my tape recorder. Ross had long since become accustomed to its blinking red on-light in hours of past interviews.

As Ross eased his weight from one side of the chair to the other, I began with a few easy questions. Then, for the first time, he acknowledged the palpable tension between him and Nicholas, which I had discovered from other sources. He said yes, there were routine "differences of opinion.'' Whenever I'd asked him in the past how they were getting on, Ross had dissembled, invoking his favorite adjectives: "It's really a fantastic relationship, wonderful." (Dick Munro correctly observes that "when Steve doesn't say someone he works with is the most wonderful person in the world, you know there's trouble.")

I explained that my book was about to go to press and I was obliged to ask him one very harsh question. "Please be my guest," he said in another of his oft repeated phrases. I asked hesitantly about a new and more credible revival of an old rumor, "that you have cancer. Is it true?" "No, without any equivocation," he replied with a half-smile.

It was then Ross's turn to ask questions. I told him that the book, which he would be reading in galleys within the month, reported all the bumps, glitches, and public embarrassments of the merger and its aftermath. A lot of people wouldn't come off very well—including him. "You and some others may never want to speak to me again," I said. "So long as it's factual," he said, "I'll have no complaints. But how is it rough on me?"

"Well, you always describe yourself as a dreamer," I answered, "and a journalist has to try to separate dreams from reality." He took the warning in stride, asked for no details, and said, "If you wrote what you honestly believe, it's O.K. with me."

"Tell me something as a friend," he said, making his customary assumption that anyone who was not a declared enemy had to be his friend. He wanted to know about "church and state," the traditional Time Inc. division between editorial (church) and business (state). "You know," he said with a pleading frown, "I've never spoken to any editor directly or through a third or fourth party about any stories in the magazines."

I mentioned that people had told me they thought he was getting bad advice—staying out of the Time & Life Building and not exposing the editorial staffs to his unique form of cheerleading and generosity. "My gut kept telling me to spend more time in the Time & Life Building," he allowed, even though his aides had advised him against it. "So it's my fault." (Disarmingly, Ross always feigns taking the rap himself whenever there is bad news.)

Ross, who never saw a budget or salary that couldn't be increased, said he felt strongly that the editorial and publishing people in the Time & Life Building had been treated badly and were "being screwed" financially. "Turn off the tape and I'll tell you what I'm thinking about doing." Off the record, he outlined some financial initiatives he was considering to improve the "pocketbook morale" of the company's print side.

"My gut kept telling me to spend more time in the Time & Life Building," Ross allowed. "So it's my fault."

He sought more information on what the book said about the decline of his reputation and the sinking morale in the Time & Life Building. "Tell me and save me the cost of buying a copy of the book," he joked. Then, name by name, he wanted to know what was reported about the people on the magazines. He listened with rapt attention because, as he put it, "I'm in a world I've never been in before." When his list came to McManus's deputy, the editorial director, Ross made his most affirmative personnel evaluation: "Dick Stolley, I really like him, he's terrific."

But Ross's strength was obviously waning. Without asking, I rose to leave, escorting him to the winding stairway leading to his bedroom upstairs. He ascended painfully, clutching the handrail. Over his shoulder he said, "Thanks for distracting me."

He allowed himself to be distracted once more—for a retrospective on Ross and the merger in The New York Times Magazine. Then, two days before Thanksgiving, his lawyer and intimate friend Arthur Liman phoned. Liman sounded uncharacteristically distraught. "You're the first call I'm making—and I'm making a lot. We're announcing in half an hour that Steve is beginning treatment for prostatic cancer, but Steve wanted me personally to call you first. One of the things that has caused him an enormous amount of anguish is that when he talked to you he denied it. They misdiagnosed his problem for several weeks. It's a stunner for him because he thought that the last thing in the world he would need is this treatment. The doctor I spoke to is very optimistic."

Senior politicians now must give brutally detailed reports about their health. The S.E.C. has no such imperative for C.E.O.'s. A strong case could be made that the leading figure in a huge public company with tens of thousands of employees and many more stockholders should be held to the same standard, even though it would violate the compassionate privacy rights accorded others. Time Warner board members have been heard to complain that they lack that kind of information about Ross. Today, Steve Ross, sixty-four, has settled into his East Hampton house and his Manhattan apartment, taking a course of six debilitating and risky chemotherapy treatments, each of which must be separated by twenty-one days. By early March he had completed three. He has temporarily lost his silver mane and has suffered transient infections, both common side effects of such therapy. Levin reports that a tumor pushing on Ross's spine, which caused the initial pain, has shrunk by 80 percent.

Between treatments, Ross summons up his energy to engage in his favorite activity, work. Even though he doesn't go to the office, he is frequently on the phone to associates and board members. His wife, along with his longtime assistant, Carmen Ferragano, who knows his every move and instinct, relays messages and instructions from him. Levin, who visits Ross, says that from what the doctors report he expects Ross back in the office this spring.

A new most happy couple? Who knows? Certainly this one has more potential for success—if Ross's treatment allows—than the unhappy two-year marriage of Ross and Nicholas. Says Levin optimistically, "Steve and I, Time and Warner, have a common purpose for the company. And it's a higher obligation than simply making money."

Does Levin really mean these lofty words? "You can be certain I do," he says. "My integrity is at stake." It sure is.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now