Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowIn a new book, Sarah Weddington, the attorney behind the landmark Roe v. Wade decision, reveals how her battle for women's rights blighted her own career

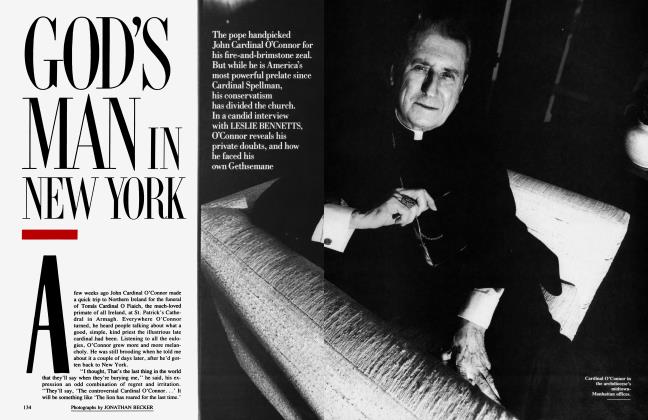

September 1992 Leslie BennettsIn a new book, Sarah Weddington, the attorney behind the landmark Roe v. Wade decision, reveals how her battle for women's rights blighted her own career

September 1992 Leslie BennettsShe was a Methodist preacher's daughter who sang in the church choir and performed Sunday devotionals, a stellar student and president of the Future Homemakers of America in high school, an earnestly ambitious girl who was a full-time law student while working several jobs to pay her way, and who had never broken a law in her life. She had a boyfriend who was also planning to go to law school, and they had started talking about marriage. They had never used birth control. And so when she became pregnant, and realized that having a child would mean the end of all her hopes for escaping from the kind of lifelong domestic frustration that had imprisoned her own dour, unhappy mother, she and her boyfriend drove across the Texas state line one weekend to a dusty Mexican border town where, for $400—a sum greater than her entire life savings—she was relieved of her pregnancy and handed back a shot at the future she had hoped for. She and her boyfriend drove home to Austin, and she was in class on Monday morning. And she never talked about it again, not for a quarter of a century—not even when she began to spend all her waking hours speaking and writing about abortion, not even when she herself became famous for overturning the laws that had made such a frightening and dangerous trip necessary in the first place. Never talked about it, that is, until now.

Sailing slowly into the room with the stately grace of an ocean liner, Sarah Weddington hardly looks like a revolutionary. With her bulky form neatly attired in a purple suit and tasteful jewelry, her graying hair carefully secured in a bun, she could be any buxom suburban matron in town to lunch before a matinee, instead of someone who changed the world. As she settles herself at our table, no one in the restaurant gives her a second glance.

It has been two decades since Weddington—then a shockingly young and inexperienced attorney barely out of law school—found an abortion case suitable to challenge the Texas state law prohibiting abortion, argued it before the Supreme Court, and won the verdict that became known as Roe v. Wade, establishing the legal right to abortion for the first time in American history and altering millions of women's lives forever. Weddington was the least likely prospect one could imagine for such an extraordinary role: she had never practiced as a lawyer, and she was only twenty-five years old when she first appeared before "the Supremes,'' as she thought of them, to present the victorious argument that abortion is a choice guaranteed by the right to privacy. The rest-room facilities for the Supreme Court bar were for "Men Only,'' but when the Court's decision was announced on January 22, 1973, Weddington's place in the history books was instantly secured.

By then she had run for the Texas state legislature, edging out a primary opponent who refused to call her by name and referred to her only as "that sweet little girl." Her unexpected victory provided a political springboard that eventually catapulted her to Washington for a high-profile job at the White House during the Carter administration. Those were heady years: scarcely past thirty, Weddington seemed surely destined for greater glory. Her fierce ambition cloaked by a soft southern drawl, the prim and proper young special assistant to the president looked more like a 1950s schoolmarm than a feisty young feminist in the vanguard of the sexual revolution. While others flaunted their blue jeans and long hair, Weddington stuck to her stodgy middle-aged suits and librarian's hairdo. If her public persona was a startling anachronism among her peers, it was also a major asset on the political scene. Weddington's old-fashioned feminine gentility, enhanced by a diplomat's skill at compromise, made even the most inflammatory new ideas seem palatable and unthreatening. No one who knew her then would have been surprised to see her end up as a Cabinet officer or in the Texas governor's mansion.

How did it all go so wrong? Instead of moving on to bigger things, Weddington has spent the last dozen years in political limbo, struggling to make a living while men of lesser achievement were assured big-bucks jobs at high-powered law firms. Seventeen years ago Weddington gave a lively housewife named Ann Richards a job as her administrative assistant; now Richards is governor of Texas, and columnists tout her as a presidential prospect for '96, while Weddington, even in the estimation of her most admiring friends, couldn't get elected dogcatcher back home in Austin. At forty-seven, she has become a living footnote, her career a long study in anticlimax, her opportunities eternally blighted by the very breakthrough that made her famous. As the twentieth anniversary of Roe v. Wade approaches, Weddington's singular accomplishment survives by a fragile one-vote margin, and if George Bush is re-elected president the landmark decision she once thought had liberated women forever may well be thrown out before another year has passed.

They never planned to make history. Indeed, back in the 1960s, when a group of women organized a referral project at the University of Texas to dispense information on birth control and abortion, the effort seemed a purely local matter of responding to the constant need of desperate young women looking for "the good places to go" to terminate unwanted pregnancies without risking their lives. Sarah Weddington, who had graduated in the top quarter of her class at law school but couldn't find a job with a law firm because no one seemed willing to hire a woman, was working for a former professor when she was asked to do some legal research for the referral project, whose volunteers were concerned about whether they could be prosecuted as accomplices to the crime of abortion. Such were the almost accidental beginnings of Weddington's expertise, according to A Question of Choice (Grosset/Putnam), her new book about the events leading up to and following from Roe v. Wade. As Weddington researched anti-abortion statutes and court cases around the country, she did become an expert, but when her colleagues decided to file a lawsuit to challenge the constitutionality of the Texas law banning abortion, Weddington was chosen as the attorney mainly because nobody else would do the case for free.

Weddington enlisted the help of a former classmate named Linda Coffee, and set about finding the right plaintiff. The first choice was a woman with a neurochemical disorder that would be worsened by pregnancy; she and her husband became known as John and Mary Doe. Also needed was a woman who was actually pregnant; a friend in Dallas finally came up with Norma McCorvey, the waitress who would be immortalized as Jane Roe. Weddington and Coffee met her in a pizza parlor. McCorvey had never finished the tenth grade, she wasn't married, she already had one child her mother was raising, she could barely support herself, let alone anyone else, and she would lose her job if she continued her latest pregnancy, the result of a casual affair. She also had no money to travel to another, more hospitable state.

"For this very sheltered woman to go to Mexico to have an abortion—she must have been scared to death," a friend says of Weddington.

Weddington and Coffee filed the Roe and Doe lawsuits against Henry Wade, the district attorney of Dallas County. Their argument maintained that the existing Texas law violated a fundamental individual right to privacy secured by the First, Fourth, Fifth, Eighth, Ninth, and Fourteenth Amendments. Before going to trial, they expanded their suits to class actions, fearing that otherwise, after Jane Roe gave birth, her case might be judged moot and thrown out of court.

In June of 1970, a three-judge panel declared the Texas law unconstitutional, but the decision was a mixed blessing. It came too late to help Jane Roe, who had her baby early that summer and gave the infant up for adoption. The federal judges also dismissed the Doe case for lack of standing, since Mary Doe wasn't actually pregnant, and they refused to order the Dallas D.A. not to prosecute doctors for performing abortions. Wade promptly announced that he would continue to prosecute, thereby enabling Weddington and Coffee to appeal the case directly to the Supreme Court.

Weddington initially argued Roe v. Wade before the Supreme Court on December 13, 1971, but instead of handing down its decision the following spring, the high court notified her that Roe would be re-argued in October, an unusual procedure that spawned a variety of rumors; one held that President Nixon, who was opposed to abortion, didn't want the case decided while he was running for re-election (a set of circumstances Weddington suspects may have a contemporary parallel in the Bush presidency). So that fall, in the middle of her campaign for the state legislature, Weddington drove back to Washington in a friend's car, camped out on another friend's pullout couch, and went through the whole exercise again. Three months later the Supreme Court ruled that Texas's anti-abortion statute was unconstitutional because it violated the constitutional right to privacy.

The first time Sarah Weddington wrote A Question of Choice, it came out as the kind of calm, impersonal, lawyerly chronology one might come across in a textbook. Nowhere in the original manuscript did one find any hint of Weddington's personal experience, one she had never planned to reveal. She had always kept her own abortion a secret, she says, because "it's the principles that are important. But today is a time when more women are going to have to talk about their own experiences. It's the best way I know now to get some attention for the issue."

She was a twenty-two-year-old law student when she got pregnant; her parents were already supporting two other children in college on their minimal income, and her boyfriend, Ron Weddington, was still finishing his undergraduate degree. "I wasn't ready to get married, and I was mortified," she says. "At that point, you had kids, you had to quit work. I couldn't have finished law school, and Ron's chances of finishing would have been dramatically lessened. The whole plan I had for my future would have been impossible."

She was lucky: Ron found the name of a reputable practitioner in Piedras Negras, and there were no complications, medical or emotional. Sarah and Ron later got married, although they divorced in 1974, and Sarah's decision not to have children was indeed a matter of choice, rather than the forced result of a botched abortion, as was the case with so many other women during those terrifying years when an unwanted pregnancy could mean mutilation or death.

When I ask her if the abortion was traumatic, she says fervently, "Being pregnant was traumatic." Weddington is not one to indulge in any self-dramatizing histrionics. "Other women went through some really horrendous things; I didn't," she says, her tone businesslike. "I was much more sympathetic to other people's stories than I was to mine. I wish I hadn't been pregnant, but having been pregnant, having an abortion was the right thing for me, and I'm glad I did it."

However, her friends remember only too well what things were like back then. "For this very sheltered young woman to go to Mexico to have an abortion—she must have been scared to death," says Barbara Vackar Cooke, an Austin political consultant. "The stigma, the disgrace, the real, real danger—unless you lived back in that time, these younger women have no idea of what it was like to not have abortion as a safe option."

Weddington also minimizes any angst she may have suffered over the demise of her marriage; her explanation is as self-effacing as it is generous. In Sarah's version, Ron, with whom she once shared a law practice, was smarter than she and far more sophisticated; he broadened her horizons, helped her with Roe v. Wade, supported her successful campaign for the Texas legislature even though he had previously lost his own run, and generally behaved as the model of a liberated man. "But I sensed that it was grating to him. . .not to be receiving equal public attention," she writes tactfully in her book. As she explains the divorce, they simply drifted apart.

Her friends fill in some of the blanks. "Ron was egotistical and narcissistic, and he never gave her any credit for what she was doing," says Patty Rochelle, a lawyer who knew them both. "Even though he helped on the case, I think it was just devastating to his ego," says another friend. Mutual acquaintances dispute Sarah's oft repeated assessment of Ron's intellectual stature: "He thinks he's smarter than Sarah is, and he convinced her of it for a long time, but he's not," says Martha Davis, a law professor at the University of South Dakota. As for Ron's supporting Sarah's achievements, adds one former colleague, "he would do things like break in on her conversations with clients to ask her when she was going to have lunch ready."

"It is unnatural to have the peak of your career when you are twenty-seven. How do I top that?"

Ron Weddington admits he was often abrasive—"Obnoxious? Guilty!''—and felt slighted by the glory accorded his former wife. "I've always been disappointed that I've gotten so little credit on Roe v. Wade," he says. "I wrote some of the most crucial points in the brief, and I played an integral part in getting Sarah elected."

In the years since, Sarah has portrayed her failure to remarry as a simple matter of scheduling. "I was too busy," she says, her moon face smooth and devoid of subtext. "It is very hard for professional women who have accomplished a great deal or who are well known to form relationships. With a lot of busy men, what they want is someone who will be available when they have free time, and women like me are not. So those men find us wonderful as friends, or as interesting dinner companions, but they often find their romantic interests with someone else. When somebody would call me for dinner, maybe three weeks from Tuesday I was available. And I wasn't willing to change it, because I liked what I did and I was having a good time."

And as far as she's concerned, that's that; Weddington isn't one to examine her life too closely. She's never been in therapy, "and I never plan to," she says firmly. "I have my neuroses neatly stacked, and I don't want anybody to undo them; I'm not in pain, and I would be diverted from what I think is more important right now." In other words, too busy. Nevertheless, Weddington describes herself as a happy person, and says she loves her life. Not everyone is convinced. "She's just too driven," says Bradley Bryan, an old pal who is a lobbyist in Austin. "She never stays around long enough to get in a pasture and shoot some birds. She's not smiling enough for me these days." "Sarah is a worker; that's what Sarah gets fun from doing," explains Governor Richards. "She likes to make speeches, she likes to travel, she likes to work, and anything that doesn't fit into those categories, Sarah's going to be bored." From time to time, Weddington allows as how maybe she ought to make some changes. "She always says, 'I'm going to stop, I'm going to slow down,' and then she just keeps going," attests Caryl Yontz, a lobbyist for the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees in Washington. "She does not feel comfortable just relaxing; I think it makes her feel guilty. "

Some of those Weddington cites as her dearest friends admit they rarely see or talk to her, and even for those who have known her the longest, Weddington remains something of an enigma. She is so focused on her mission that she appears to have little interest in the more mundane facets of other people's lives. "She's never even met my husband or kids, and I've been married for ten years," reports Patty Rochelle, whom Sarah lists as one of her closest friends. "It's 'How's your husband—what's his name again?' " Consumed with the importance of her own agenda, Weddington can be stunningly oblivious to anyone else's needs. When she has an appointment in Dallas, says Rochelle, "she'll call and say, 'Can you pick me up at the airport and take me there, and we can visit on the way.' My goodness—I'm a practicing attorney, I'm forty-two, and I don't cart people around. I'm too busy for that." When Weddington does see friends, she is more likely to discuss politics than to plumb the depths of her own soul. "She doesn't show her emotions much," Yontz acknowledges.

In part, this is a strategic decision in response to the savage emotions surrounding the abortion controversy. "The world works a certain way, and if you're trying to change it, you've got to decide how you're going to be effective," Weddington explains. "I'm definitely self-censoring. I'm always asking myself the question, Would this be helpful?" The result is the resolutely calm, bland face Weddington so consistently presents to the world, a persona that is particularly notable in her frequent debates with such antagonists as Phyllis Schlafly. "Everyone expects me to be angry and have a big chip on my shoulder, because I'm the big feminist," Weddington says. "So part of my strategy was that if I could undercut people's assumptions about that, maybe I could also undercut some of their other assumptions. On the subject of abortion, the voices have become so angry and so loud that most people just turn them off. When I debate Schlafly, I feel I cannot afford to be angry." Her lips tighten. "But I always ask the schools to pick us up in separate cars and have us eat in separate restaurants."

Its political efficacy notwithstanding, Weddington's guardedness developed long before her career as the public emblem of Roe v. Wade. "I trained myself very early," she says carefully, "because as a preacher's kid you always had to get along with everybody. And I found I could get more done that way. ' ' Not that she was ever one of the crowd. "I think most women who go along with the system go along because they want to feel a part of things," she observes. "I never did. I always saw myself as different."

The habit of exerting constant self-control has taken an inevitable toll; Weddington is the first to admit she's not exactly a barrel of laughs. In A Question of Choice, she quotes Ann Richards as commenting, "It is not that Sarah has no sense of humor. It is just that you have to say to her, 'Sarah, this is a joke'—and then she will laugh." Typically, Weddington approached the problem like the good student she has always been. "I've learned humor," she says, beaming with pride. "I got a book called How Speakers Make People Laugh. I used to watch Ronald Reagan to see how he did it, and Bob Hope. Now I copy things down from movies." Her face falls again. "I am so serious I can be real dull," she confides.

"The abuse she has taken—people calling her 'baby killer,' people calling her at night, hollering at her with that rabid type of rage."

Perhaps this is not surprising; although Roe v. Wade constitutes Weddington's claim to immortality, it is also an albatross she will be saddled with forever. "I never wanted to be the icon for Roe v. Wade," she says with a sigh. "I would love to move on to other issues, but every time I try, this thing reaches out like a creature and pulls me back."

She was startled recently when a Seattle reporter remarked, "Your obituary has already been written. The headline says, 'Roe v. Wade Attorney. ..' " "It got me to thinking I would really like to replace that caption," Weddington says, looking wistful. "It is unnatural to have the peak of your career when you are twenty-seven. How do I top that? There's a sense of inadequacy in not being able to top it, yet I don't know how it's possible in this day and time. If I argued the same case today I couldn't win it."

Indeed, disappointment hangs over her life like a shadow. Roe v. Wade may have made her famous, but it closed some doors forever. "It has ruined her political career," declares Barbara Vackar Cooke, who worked with Weddington in the Carter White House. "She cannot hold an elective office. The abuse she has taken—people calling her 'baby killer,' people calling her on the phone at night, hollering at her with that rabid type of rage—I couldn't believe it when I lived with her in Washington. I was just horrified. She couldn't run and win anything no matter how much she wanted to."

Even if Weddington might have accepted a lucrative sinecure with a big law firm after leaving the White House, the question was moot; none was offered. Whether the stigma of abortion helped preclude such opportunities is hard to say, given such additional factors as gender bias and a dozen years of Republican rule, but certainly Weddington's speaking fee of $3,000 to $5,000 is a fraction of what a man with comparable credentials would command. She maintains her usual stoicism about all such failed expectations. "She doesn't complain," says Cooke. "She'll just make the best of it."

But Weddington's regrets are obvious when she talks about an earlier time when the future seemed so much brighter. "I look back with such nostalgia on the late sixties and early seventies—in my life, that was such a wonderful period," she says eagerly, her face suddenly alight. "I was part of the momentum, part of a national effort of women who were changing things, and we could see the results of what we did."

In more recent years, it seemed she was crying into the wind; her lecture audiences were sparse, the younger generation obviously took the right to choice for granted, and Sarah Weddington seemed like a relic from another time. Lately, however, things have changed. Ever since the Supreme Court's 1989 decision in Webster v. Reproductive Health Services, a Missouri case imposing an ominous variety of restrictions on abortion access, growing numbers of women have realized that complacency may well lose them the right to abortion, and pro-choice forces have seen a sudden upsurge in interest and support. Weddington has become a hot ticket, and she loves to tell how seats to one recent speech were so sought-after they were being sold by scalpers. Last June, the Supreme Court's 5-4 ruling in Planned Parenthood v. Casey, which upheld Pennsylvania's attempt to regulate the right to abortion, made it all too clear that Roe v. Wade now survives by a one-vote margin. Justice Harry Blackmun spelled out the danger for anyone who might have missed it: "I am 83 years old. I cannot remain on this Court forever," he wrote plaintively. In the aftermath of the Casey decision, with the proposed Freedom of Choice Act percolating in Congress, Weddington and her purple suit became regulars on the talk-show circuit again—and if the Court's ruling was somewhat murky, Weddington's message is not. ''This just makes even more important who's president—who gets to appoint the next Supreme Court justice, and who's got veto power," she says.

The future of Roe v. Wade may be uncertain, but Weddington's was decided a long time ago. "She has this terrible burden, and it has altered her life," says Terry Saario, the president of the Northwest Area Foundation in St. Paul, Minnesota, and a longtime friend. "But she has chosen to say, 'Whether I like it or not, Roe v. Wade is me, and I'm going to go ahead and try to be a voice for Roe v. Wade, and particularly to try to reach younger women.' " Right now Weddington's mission is filled with a sense of urgency; if George Bush retains the White House and Roe falls, the state-by-state battle in legislatures around the country will become critical. That message is apparently getting across. "Sarah came up here to speak at the Minnesota Women's Campaign Fund fund-raiser, and not only was she a draw, we had to turn people away," Saario reports. "She is a symbol of what we all hold dear, and it was very clear that this audience felt very strongly about this issue. At the end she had everyone in tears about what would happen if we lost that right. She got a standing ovation, and people just wouldn't leave. One woman decided to run for office as a result of Sarah's speech."

For Weddington, such satisfactions help make her frenetic life worthwhile. Wherever she goes, people come up to tell her about their own experiences, about the nightmares that won't go away no matter how many decades have passed: about the sixteen-year-old girlfriend who started hemorrhaging after a botched abortion, about the mother who died because she was pregnant and her husband had left her and she couldn't support any more children, about the wife who was never able to have her own baby because the infection from a back-alley abortion when she was a schoolgirl had left her sterile. These are the people who remember all too well what it was like when women resorted to knitting needles and telephone wire, curtain rods and coat hangers to try to terminate a pregnancy, desperately injecting lye or Lysol into their bodies or connecting a vacuum cleaner in a crude attempt at vacuum aspiration that could extract the uterus from the pelvic cavity and kill a woman almost instantly. These are the memories that keep Sarah Weddington going no matter what the cost to what might otherwise have been her personal life.

And there is always the memory of that one shining moment to sustain her. Roe v. Wade may seem like ancient history to the young, but its impact is still felt every time a woman gets pregnant: more than a million American women have had safe legal abortions every year since 1975, and countless more have had the option. "At least I can point to something very concrete that affected millions of women," Weddington says with quiet pride. "I don't resent it, because it's such a plus for anybody to be able to say, 'I really did something significant, and it was something I really care about.' Everyone wants to feel their life stood for something and they made a contribution—and I did."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now