Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowSINATRA'S DOUBLE PLAY

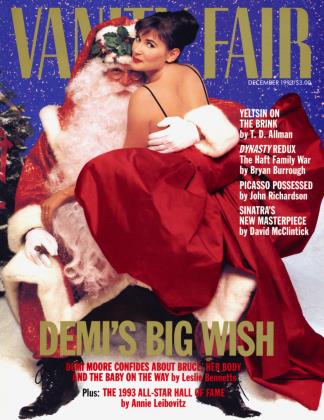

Frank Sinatra, who turns 78 this month, is releasing Duets, his latest timeless effort: a collection of standards with stars from Aretha and Julio to Bono and Barbra. Clearly, the Chairman of the Board is not ready to step down

DAVID McCLINTICK

Show Business

I met Frank Sinatra on a hot August evening in New York in 1979. He was in a deeply air-conditioned CBS studio on East 30th Street recording songs for a three-disc album called Trilogy, for which I was to write liner notes. I had been listening to his records since I was a teenager, having found myself drawn to Sinatra as the most compelling performer of the best American popular music. Though his nonmusical antics sometimes distracted him and us, he seemed to understand what to my young ears was a basic truth about music—that much of it expresses yearning, yearning for romance in all its incarnations. Sinatra yearned better than any other singer I had ever heard.

The physical atmosphere of the 30th Street studio, like all recording studios I had ever been in, was cold and intimidating. It reminded me of a large, shadowy cavern. Stalagmites—in the form of music stands, microphone stands, and speakers—rose from the floor. Stalactites—in the form of naked 200-watt lightbulbs and microphone booms—hung from above. State-of-the-art equipment gleamed and blinked, ready to record every sound Sinatra and the 56 musicians emitted.

Everyone is tense in recording studios, but Sinatra was perhaps the least tense person in this one. He had just returned from the South of France and sported a golden tan. Wearing a beige leisure suit, open yellow shirt, and dark horn-rimmed glasses, he stood next to his arranger-conductor, Don Costa, humming through Costa's orchestration of the Billy Joel standard "Just the Way You Are." Sinatra was in the midst of a career renaissance that had begun a few years earlier in the mid-70s when he regained his vocal moorings after "retiring" from 1971 to 1973. Trilogy, his most ambitious recording ever, included contemporary songs made famous by much younger artists, as well as older songs that Sinatra had never recorded and a suite of original songs about Sinatra's life composed by Gordon Jenkins.

A month later, in Los Angeles, after more Trilogy sessions, including one where Sinatra recorded Kander and Ebb's "New York, New York," he took a small group of us to dinner. His favorite pizza joint was closed, so he chose Pip's, a private club in Beverly Hills. Frank drove his wife, Barbara, in an unpretentious Mercury station wagon. I followed in my rented Ford. After a couple of blocks I instinctively flicked on the car radio, and by a kind of magical coincidence, a Sinatra record came blaring forth. It was "I'll Be Seeing You," the up-tempo version. As I followed the Mercury, observing Frank and Barbara conversing and gesturing like any other couple in cars around us, his singing voice, framed by Sy Oliver's big-band riffs, filled my car:

I'll be seeing you

In all the old familiar places

Crossing La Cienega on Beverly Boulevard, I ran a red light to keep up with the Mercury.

I'll find you in the morning sun And when the night is new.

At Pip's we drank—I drank too much —and talked until two A.M. about everyone and everything from Louis B. Mayer to William Styron. We did not talk in detail about the Trilogy project, however. I had asked to interview him for my liner notes, but he had declined, indicating through an aide that he wanted me to "write about the music."

Fourteen years later, Thursday, July 1, 1993— another hot summer night in another chilly studio. Now it is Sinatra's turn to feel the tension. Microphone in hand, he is perched on a stool at the center of Studio AB on the ground floor of the legendary Capitol Records Tower in Hollywood. He is wearing a dark suit and tie, and a beach tan. A 52-piece orchestra, ready to play, surrounds him. Conductor Patrick Williams, at a podium to the singer's right, gives final instructions to the musicians. Behind the glass of the dimly lit control room, producer Phil Ramone and several technicians wait expectantly at a twinkling 48-track console.

Frank Sinatra has made only two records since Trilogy, the last in 1984, and some critics say that is just as well. They say that Sinatra, who turns 78 on December 12, should retire from recording, and from performing altogether. "Frank Sinatra should be elevated to Chairman of the Board Emeritus," wrote Wayne Robins in Newsday in June after an erratic Sinatra concert on Long Island. "He should retire with dignity." There are days when Sinatra agrees. His singing voice has naturally lost some of the power— it's debatable how much—that established him long ago as the 20th century's definitive interpreter of American popular music.

'There is only one way I'm going to sing," Sinatra said, "and that's in the room with the band."

Still, Sinatra has come to Capitol this evening to try something he has never done before, an album of duets on some of his classic songs with other world-renowned singers. The others, who include Barbra Streisand, Bono of U2, Aretha Franklin, Carly Simon, Tony Bennett, and Julio Iglesias, are not present. Their voices will be added to the recordings later if they agree, and if Sinatra's own plans proceed. A big if, it turns out. Sinatra is struggling.

Tonight is the third time this week that he and the orchestra have gathered. On Monday night, the producers asked Sinatra to record his vocals from a soundproof booth. That's the way most recordings are made nowadays, with the singer and each instrumental section isolated from one another and recorded on separate tracks, so that artists and producers can later "mix" the sounds to their liking and correct errors. This approach minimizes the spontaneity and intimacy with the orchestra that Frank Sinatra has always insisted on. After trying two songs in the booth, Sinatra emerged.

"This isn't for me," he said matter-of-factly. "I'm not singing in there. There is only one way I'm going to sing, and that's in the room with the band."

The next night, the producers tried to get Sinatra to wear earphones and record his voice over instrumental tracks already laid down by the orchestra. Again, he felt uncomfortable and recorded nothing.

Now Capitol executives are anxious. Money is flowing. Hopes are not high. There is an understanding that if this third try doesn't produce something, the duets project and Frank Sinatra's recording career may be abandoned, perhaps forever. Tonight the producers have tried to simulate some of the conditions of a concert, the setting in which Sinatra is most comfortable. They have positioned the singer on a small, low stage with the same cordless, handheld Vega microphone that he uses when performing live. His pianist of 42 years, Bill Miller, is seated straight ahead at a Steinway grand.

Only seconds before Patrick Williams's downbeat, Sinatra hesitates. "Why the hell am I doing this?" he asks his co-producer Hank Cattaneo with a sense of frustration. "Why am I recording all these songs again?"

Continued on page 62

Continued from page 52

Frank Sinatra has cold feet—not the shaky ones of a scared novice but rather the well-planted cold feet of the most seasoned of professionals. Sinatra remains the ultimate perfectionist. He is about to do something daring—and to do it in the same studio where in the 50s he made some of the most famous records in the history of recorded sound. He doesn't want to embarrass himself now. How will his aging voice sound on this new recording? Sinatra wants reassurance that the producers have thought of everything. What if his singing, his orchestrations, his keys, his tempos, his range, are not compatible with those of the other singers?

"How will you work these things out with them?" he asks Phil Ramone, who has emerged from the control booth to join the conversation. Sinatra has pressed such questions for weeks in meeting after meeting. It's not that he doesn't trust his production team, all of whom have worked with him before. Ramone, known as "the Pope of Pop," is one of the top record producer-engineers in the world, having made albums with countless artists, including Billy Joel, Paul Simon, and Barbra Streisand. The equally eminent Patrick Williams has orchestrated albums for those three, among others, and has written the music for a host of motion pictures and television shows. Hank Cattaneo, the closest of the three to Sinatra, has toured as his production manager for a decade and has run many notable live performances, such as Barbra Streisand's concert in Central Park and the Beatles at Shea Stadium. Now, on this uncertain Thursday evening, they review their plans again and try to reassure Frank Sinatra.

' 'Let's do a couple of tunes, Frank, just to see how it feels," Ramone suggests.

"This better work," Sinatra mutters, still unconvinced. Ramone returns to the booth, and Sinatra nods to Pat Williams, who strikes up Jimmy Van Heusen and Sammy Cahn's "Come Fly with Me," written for the Sinatra album of the same name in 1957. Sinatra still opens concerts with "Come Fly"; he is as comfortable singing it as he is any song. Tonight, he does two partial takes and a complete one, which sounds fine. So far so good.

"Next tune," he says. Cole Porter wrote "I've Got You Under My Skin" for Born to Dance in 1936. Sinatra recorded it 20 years later in this same room with the legendary arranger Nelson Riddle conducting some of these same musicians, including bass-trombonist George Roberts, who helped Riddle conceive the orchestration, one of the most famous in popular music. To this day, audiences demand that Sinatra sing "Skin" at nearly every performance. The producers have penciled in Julio Iglesias as one candidate to sing the song with Sinatra. Now, a few bars into the introduction, Sinatra raises his hand toward Pat Williams.

"Hold it," he says. The orchestra stops. Williams looks at Sinatra, who is tapping two fingers rhythmically on his right thigh, refining the tempo slightly. Williams starts the orchestra again. There are three more false starts before a complete take is laid down. Twenty-two takes were required to complete the original recording in 1956.

"What you got?" Sinatra asks, feeling more sure of himself.

" 'Tramp.' "

"Shoot," Sinatra says. After a false start, Rodgers and Hart's "The Lady Is a Tramp" is finished in a single take. Sinatra feels good. His voice is clear and strong, in marked contrast to the way he sang at the concert the Newsday critic heard just three weeks ago tonight, when Sinatra was jet-lagged after a grueling European tour. Ramone, Williams, and Cattaneo are beaming, as are the musicians. All of Sinatra's uncertainty is gone. He is in command, like a general on the march. Though it is unusual to record more than three songs at one session, everyone presses ahead, sensing that a window of opportunity has opened and may close at any moment. They lose track of time and miss the first scheduled break required by the musicians' union rules. Nobody complains. Sinatra and the orchestra record Harold Arlen and Ted Koehler's "I've Got the World on a String," the Gershwins' "They Can't Take That Away from Me," and Cole Porter's "I Get a Kick Out of You."

"Why the hell am I doing this?" Sinatra said. "Why am I recording all these songs again?"

"Anybody dizzy besides me?" Sinatra asks after the soaring finish of Rodgers and Hart's "Where or When." There is a burst of nervous laughter. They complete nine songs in all, including "One for My Baby," which Johnny Mercer and Harold Arlen wrote for Fred Astaire in 1943, and which Sinatra later made his own as a classic saloon ballad of the ravages of lost love. Accompanied only by his pianist and a few strings, Sinatra sings the song through once. Holding the latest of many Camel cigarettes he has smoked this evening, he concludes:

... so make it one for my baby . . .

and one more for the road . . .

that long . . .

that long . . .

man it's long . . .

it's a long . . .

long . . .

. . . long . . . road.

There is just a slight catch in his voice, as if he's nearly overcome with emotion. The studio and control room are silent. Then the entire orchestra stands and applauds. Sinatra's guitarist, Ron Anthony, tries to swallow a lump in his throat, sensing a "raw emotionality" about the performance that somehow encompassed all previous performances of the song. "My God, he's telling his own story," says violinist Gerald Vinci, who played on the original Capitol recording of "One for My Baby" in this studio 35 years ago almost to the week. "That's the best thing I've ever heard him sing— or say. He acted the song," says basstrombonist Roberts, who played at his first Sinatra session in 1953.

Exultant but exhausted, Sinatra calls it a night just after 10 P.M. It has been a transcendent evening, but doubts still haunt Sinatra. Will other artists actually agree to sing with this nearly 78-yearold man?

Sinatra leads a simpler life these days than he used to. He no longer combines carousing until dawn with shooting movies all day. Though his temper still flares, it's been years since he got into a fight, clashed with a photographer, feuded with anyone publicly, or fired off an angry telegram to a gossip columnist. He still drinks, smokes, and stays up late, but he devotes virtually all his energy now to what he has always enjoyed mostsinging before large groups of people. When he's not on the road, he lives quietly in California—Malibu in the summer, Palm Springs in the winter. But the lion is still roaring, still irrepressible, still feisty, still difficult, and still the most potent singer of songs who ever lived.

The nine recordings made in the Capitol Tower on July 1, together with several more that Sinatra completed shortly thereafter, represent his best singing in years. The other artists, including Streisand and Bono, have eagerly recorded their contributions in studios all over the world. The result is an album that is remarkable not only for its entertainment value but also for its symbolic importance. Frank Sinatra Duets signals a late, dramatic, and unexpected surge in what already stands as the most extraordinary career in the history of popular culture, surpassing those of Bing Crosby, Elvis, Judy Garland, the Beatles, the Rolling Stones, Chaplin, Garbo, Brando, and all other contenders.

America and much of the world in late 1993 are pulsing with the music of Frank Sinatra. Capitol Records is spending millions of dollars to make Duets the biggest-selling Sinatra album ever, outdistancing even his No. 1 best-sellers from the 50s, such as Come Fly with Me and Only the Lonely, and the 1965 classic, September of My Years. Music associated with Sinatra is being recorded by artists ranging from the Boston Pops to punk-rockers. Columbia Records has just released an elaborate boxed set of all 285 recordings Sinatra made for Columbia between 1943 and 1952. Sinatra is the artist of the month for December on the hip cable music channel VH-1. Two nationally syndicated all-Sinatra weekly radio programs are adding stations, and a third program wields national influence from New York City.

None of this activity stems from sentiment. The recordings, the radio programs, the television exposure, and Sinatra's busy concert schedule all are profit-motivated, reflecting a continuing, strong demand for Sinatra's services. And the demand is not driven just by nostalgia. Some of his most avid fans now are under 30 years old.

Why is Frank Sinatra timeless?

Beyond his talent and magnetism, which are unmatched, he embodies—in a public and very provocative way—many diverse elements of America's spirit during the middle and late 20th century: swagger, virility, compassion, generosity, ethnicity, disputatiousness, broad humor, blood loyalty, and a volatility of temperament that is occasionally exuberant and occasionally dark. An extraordinary array of people, from paupers to potentates, American and foreign, have long identified with Frank Sinatra as they have with no other entertainer. No matter how outrageous his conduct on occasion, we come back, because he continues to touch our emotions.

To hear the Duets album in advance of its release, and to get a sense of how Sinatra sounds and looks in concert in late 1993, I decide to venture to Las Vegas, where he is singing at the Desert Inn for six nights. It is late September. Las Vegas feels different. When I was last here, in the late 70s, the atmosphere was still loose and reckless. Now kids' circuses and treasure islands abound, and the city seems obsessed with security. It is easier to get into the Pentagon than into my room at the Mirage, where I stay for the first two nights because the Desert Inn is overbooked with Sinatra fans. The D.I., as the taxi drivers call it, is a bit shabby, awaiting new management from I.T.T. Sheraton, which recently bought it from Kirk Kerkorian. When Howard Hughes owned it, he lived in the penthouse for four years.

Though his temper still flares, it's been years since he got into a fight, clashed with a photographer, or feuded with anyone publicly.

Frank Sinatra made his Las Vegas debut here in September 1951, 42 years ago. It was here during that engagement that he met Bill Miller, the pianist who has been with him more or less ever since. The older Sinatra gets, it seems, the more excitement his concerts generate. The audience comes to witness Sinatra versus his circumstances. When I arrive at the Desert Inn for his show in the big room on Tuesday, September 21,

I sense something akin to what I felt the previous Saturday at Yankee Stadium. Can the Yankees beat the Red Sox and stay in the race? Is Wade Boggs too old to make the big plays? At the Desert Inn the audience is asking, Can Sinatra keep performing for a few more years? Can he still hit the high notes?

People start lining up before six o'clock for Sinatra's nine P.M. opening in the Crystal Room. These people booked reservations months ago for first-comefirst-served seats at $75 each. The worldweary maitre d' politely banishes those without reservations. The fans in line are talking about two things—the new album, which they haven't yet heard but are excited about, and the Newsday review calling for Sinatra to retire, which has been widely photocopied.

I have never been part of any other audience as eclectic as Sinatra crowds. "It's amazing how young his audiences are," says a Desert Inn lighting technician, who looks down on the backs of nearly 700 heads from his booth each night. "When Steve and Eydie are here, most of this hair is white—or blue."

The Sinatra crowd is Guys and Dolls meets the Knicks-Lakers meets the Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center. There are a few tuxedos and gowns, lots of designer suits and dresses, and lots of jeans and polyester. A tall young black woman struts through the crowd in silver hot pants. There are three fat men in golf shirts. An owlish collegeage youth in a blazer and wrinkled chinos concealing a tiny tape recorder is shown to a seat in the back. A bearded 30-ish man in a gray tweed sports jacket and jeans whispers to a rail-thin dark-haired woman in a skintight beige minidress. There are many middle-aged Middle Americans in high-collared dresses and conservative Kiwanisand Rotary-pinned suits. A teenage boy in a plaid shirt sits with his parents. A ravishing blonde woman in a red dress makes her way on crutches to her seat. There are groups of wellturned-out Mexicans, Argentineans, and Filipinos. Three wan Japanese men in casual white shirts are ushered into a high-roller banquette. There is a man covered with tattoos, a woman in a wheelchair, and a couple waving autograph books above their heads at no one. Plainclothes security men with walkietalkies ease through the crowd.

The seating is so close in Vegas rooms that strangers quickly become either friends or enemies. I am at a table with a couple from London and a young university president from Arkansas, who tells us he saw Sinatra in the elevator in a warm-up jacket carrying his tuxedo. "He looks great," the university president says. "He doesn't look anywhere near 77."

Promptly at nine the huge crystal chandelier dims and the red velvet curtains part to reveal Sinatra's son, Frank junior, 49 years old now, conducting a 35-piece orchestra in a medley of Sinatra songs—"I'll Never Smile Again," "Leamin' the Blues," "Nice 'n' Easy," "That's Life," and "Put Your Dreams Away." A young comedian, Brad Garrett, takes the stage and tells insult jokes for 20 minutes.

"Hey, lady, you're supposed to tease your hair, not piss it off. ' '

At 9:25 the curtains open on the orchestra again. "Ladies and gentlemen, OF Blue Eyes," intones the public-address announcer. Sinatra has been standing next to the piano with his back to the audience. He turns around and is greeted

with a prolonged standing ovation. Silver-haired, tanned, and dressed in an immaculate black tuxedo with an orange pocket handkerchief, he smiles, moves to the front of the stage, waves, bows, and repeats "Thank you" into his cordless microphone. When the applause fades, Frank junior downbeats "Come Fly with Me," which Sinatra has sung live thousands of times since he recorded it in 1957. Then he moves directly into Cahn and Van Heusen's "My Kind of Town" and Cole Porter's "At Long Last Love."

"Oh, Mexico," Sinatra says. "I got drunk in your country once."

Is it the cocktails, this feeling of joy,

Or is what I feel the real McCoy?

His voice is sure and strong. As always, he acts the lyrics, listening to them as he sings, relying less on the TelePrompTers than he did the last time I saw him.

"This is a good song and gets better every year," he says of Harold Arlen and Johnny Mercer's "Come Rain or Come Shine." And then there is "The Lady Is a Tramp," which in Sinatra's hands is always an event. Rodgers and Hart wrote it for a woman to sing in the first person in Babes in Arms in 1937. Sinatra adapted it to seduce Rita Hayworth in the movie version of Pal Joey in 1957. Since the early 1970s he has sung it to a rousing big-band orchestration written by Billy Byers for the Madison Square Garden "Main Event" tour. At the conclusion of "Tramp," Sinatra heaves a sigh and mops his brow.

After "Fly Me to the Moon" and "Strangers in the Night," a woman at the edge of the stage extends a huge bouquet of irises toward Sinatra.

"Can you roll that up and smoke it?" he asks with a smile. The audience roars. He hands the woman his orange handkerchief and accepts the flowers, which are accompanied by a single long-stemmed red rose for Frank junior.

As the thumping bass introduction to "Mack the Knife" begins, he doesn't identify the song but lets the audience recognize the lyric, which it does with explosive applause.

Oh, the shark has pretty teeth, dear,

And he keeps them out of sight.

This is a smoking rendition of the Kurt Weill classic, five minutes long. Women stand and sway in time to the music. The audience cheers at the end.

The lights fade to a single spot, and Sinatra settles on a stool in front of the piano.

"I've been singing saloon songs since there were saloons," he says, lighting a cigarette and introducing "Angel Eyes," the last song he performed before he "retired" for two years in 1971 at age 55.

Angel eyes,

That old devil sent,

They glow unbearably bright,

Need I say that my love's misspent Misspent with angel eyes tonight.

The audience is silent as he concludes:

I gotta find who's now number one, And why my angel eyes ain't here. 'Scuse me while I disappear.

The spotlight follows him offstage and fades to black.

He returns for "My Way," whose lyrics, "And now, the end is near," seem less banal and more poignant, and "New York, New York," which has closed most concerts since he first performed it, 15 years ago.

The audience rises and cheers again, and the orchestra plays Gordon Jenkins's "Goodbye" as he leaves. There is no encore. There rarely is. I picture Sinatra upstairs in his penthouse grabbing a drink and flicking on CNN before the applause dies.

The Duets album is previewed for me the next afternoon in a private room at the Desert Inn on a small Sony cassette player equipped with earphones. Frank Sinatra has always loved singing duets. Some of his most memorable moments are with other performers, but relatively few of them have been recorded. The impetus to make Duets flowed from conversations more than a year ago involving Sinatra's manager, Eliot Weisman, producer Phil Ramone, and top officials of EMI Records Group, North America, the corporate parent of Capitol Records.

One of the highlights of Duets is Sinatra's first collaboration with Barbra Streisand, with whom he sings the Gershwins' "I've Got a Crush on You," from Treasure Girl in 1928. It was an up-tempo song until Lee Wiley recorded it as a ballad in 1939, a style that Ira Gershwin grew to like better than the original. Sinatra recorded the song in 1947 with arranger Axel Stordahl, again in 1960 with Nelson Riddle, and included it on his live "Sands" album with Count Basie and Quincy Jones in 1966. Streisand recorded it recently for her Back to Broadway album, but did not include it on the finished recording.

The Sinatra-Streisand "Crush" proved to be a formidable challenge for the Duets producers, who had the help of Jay Landers, EMI Records' senior vice president of artists and repertoire. Landers has been a close musical adviser to Streisand for years. Phil Ramone and Pat Williams, together with Landers, added a female voice to the Sinatra recording to demonstrate their conception of Streisand's part, which required, among other things, modulation between Sinatra's key on the song, F, and Streisand's key, E flat. Streisand asked for revisions. Landers, Ramone, and Williams consulted David Foster, who had produced Back to Broadway and also Natalie Cole's duet recording of "Unforgettable" with the voice of her late father, Nat "King" Cole. Foster devised a new approach to "I've Got a Crush on You." There were other refinements. Streisand was satisfied, and Pat Williams used the amended concept to write a new orchestration; Streisand recorded her part at the Todd-AO studio in Los Angeles on the afternoon of August 17. Waiting for her when she arrived in the studio was a huge bouquet of flowers and a handwritten note from Frank Sinatra. Streisand was touched, and pulled from her bag a nearly 30-year-old note that Sinatra had written her after seeing her in Funny Girl on Broadway in the 60s. She photocopied it and enclosed it with a new note thanking him for the flowers.

"My God, he's telling his own story," says the violinist.

At the recording session, Streisand asked for a new ending to the "Crush" orchestration, which Pat Williams wrote and the orchestra recorded on the spot. In the vocal booth, Streisand eased into it, singing with the orchestra and Sinatra's voice until the orchestral track was complete. She then worked on her vocal well into the evening, until she was satisfied. She had decided to add a personal reference to Sinatra in the last lines of the song, and after consulting with her friends the lyricists Marilyn and Alan Bergman, she "improvised" the phrase "You make me blush, Francis." The producers went back to Sinatra and asked if he would overdub "Barbra" for "baby" in the preceding line to balance the reference. After thinking it over, Sinatra made the adjustment on a digital tape recorder in his dressing room before a concert outside Chicago in August.

Despite the piecemeal process, which is common in recording duets nowadays, the result sounds as if Sinatra and Streisand are singing in each other's arms. The performance is a moving and utterly contemporary reading of the song—a very sensual primer on the dramatic rendering of romantic passion by two skilled actors. Sinatra sings with tender, understated passion, as a man who has unexpectedly fallen in love late in life. Streisand sings with eager, forthright desire, as a younger woman who wants him urgently, in a way she has never wanted anyone else.

Another milestone, even more ambitious musically, is Sinatra and Carly Simon singing Jule Styne and Sammy Cahn's "Guess I'll Hang My Tears Out to Dry," with Simon interweaving the Sinatra classic "In the Wee Small Hours of the Morning" as a countermelody. To fathom Simon's mastery of this material, one must go back before her My Romance album of recent years, which contains "Wee Small Hours," back before her older Torch album, which contains other saloon classics such as "Body and Soul" and "I Got It Bad and That Ain't Good," to her childhood, when she absorbed Sinatra recordings at the knees of her parents and their close friend the composer Arthur Schwartz, who wrote "Dancing in the Dark."

On Duets, Simon was originally slated to sing with Sinatra on "One for My Baby, ' ' but she found that Sinatra's definitive solo left no opening for a duet. Jay Landers suggested that she pair "Tears Out to Dry" with "Wee Small Hours" after playing "Tears" on his car stereo and singing alternative melodies against it.

Don Rubin, the executive vice president of artists and repertoire for EMI Records Group, North America, was in London in August when Charles Aznavour completed his duet with Sinatra on "You Make Me Feel So Young." On the evening of Saturday, August 21, Rubin took Aznavour to a U2 concert at Wembley Stadium, where 72,000 people cheered lead singer Bono and the band. Backstage afterward, Bono and Aznavour compared notes on Duets and Bono announced that he had chosen to sing "I've Got You Under My Skin" with Sinatra rather than "Luck Be a Lady." Phil Ramone flew in and recorded Bono at a shabby, backstreet studio in Dublin the following Thursday.

Bono (bom Paul Hewson), an avowed Christian and a vocal supporter of Amnesty International, is 45 years younger than Frank Sinatra, but the two men share a commitment to substantive lyrics and to the notion that music is undermined by a lack of melody. Bono and the better rock bands have always admired Sinatra's ability to feign singing with total abandon while staying in complete control. Sinatra's granddaughters introduced him to U2 years ago. The band has attended several of his concerts, and once he twitted them for their shabby wardrobes in a picture that ran on the cover of Time.

In his rendering of "I've Got You Under My Skin," whose tempo Sinatra had fine-tuned in the Capitol Tower eight weeks earlier, Bono combines sensuality with jest in a spirited romp.

"Don't you know, Blue Eyes, you never can win," he sings in his bedroom baritone before scatting along in falsetto over one of the most famous orchestral bridges ever written for a popular song. "Don't y'know, y'ol' fool, you never can win," Bono repeats in the second choms, before Sinatra sings the concluding "I've got you under my skin," and Bono trails off in heavy breathing.

"I hope Frank will like this—it's pretty wild," Ramone told Pat Williams when he returned to Los Angeles with the Bono recording.

Having been a candidate for "Skin," Julio Iglesias joins Sinatra on the Johnny Mercer lyric "Summer Wind" instead. The other pairings are Gloria Estefan on Mercer and Harold Aden's "Come Rain or Come Shine," Tony Bennett on Kander and Ebb's "New York, New York," Natalie Cole on the Gershwins' "They Can't Take That Away from Me," Liza Minnelli on Aden and Ted Koehler's "I've Got the World on a String," Anita Baker on Cy Coleman and Carolyn Leigh's "Witchcraft," Luther Vandross on "The Lady Is a Tramp," and Aretha Franklin on Gilbert Becaud's "What Now My Love."

The young soprano-saxophonist Kenny G, one of the biggest-selling recording artists in the world, plays Pat Williams's new arrangement of Cahn and Van Heusen's "All the Way" as a prelude to Sinatra's concluding solo on Arlen and Mercer's "One for My Baby."

Iglesias and Estefan were recorded in Florida, Bennett in New York, Cole in Los Angeles, Minnelli in Rio de Janeiro, and Anita Baker in Detroit,

Streisand pulled out a neariy 30-year-old note that Sinatra had sent after seeing her in Funny Girl.

where Aretha Franklin also was recorded. To accommodate the various locations, Ramone used a state-of-the-art digital fiber-optic system called Entertainment Digital Network, or EDNET, which allows recordings to be transmitted over long distances via leased telephone lines with no erosion of quality.

Iistening to Duets at the Desert Inn reveals to me why Frank Sinatra is singing so well on the stage in late September of 1993. Making the album has invigorated him and heightened his confidence. There is an air of defiance about his singing. On the second night of the Desert Inn engagement, Sinatra performs several songs he did not sing the first night: the Nelson Riddle arrangement of "All or Nothing at All," Victor Young's "Street of Dreams," the Gershwins' "A Foggy Day," and Rodgers and Hart's "My Funny Valentine." He sings "Valentine" to a haunting string arrangement that is used only at concerts and that has never been recorded.

After "Mack the Knife," a pale, heavy set man in a white shirt stands, waves his arms, and shouts, "Frank, you're the man, you're the greatest!"

"No, I don't want to be," Sinatra replies. "Then I got no place to go."

Another man in a dark suit hands up flowers.

"What country are you from?" Sinatra asks.

"Mexico."

"Oh, Mexico. I got drunk in your country once."

A white-haired waitress who has worked at the Desert Inn since the 50s serves a drink and murmurs, ' 'Men act like women in the presence of Sinatra."

Sinatra's close attention to tempos and keys, always evident onstage, reminds me of a moment during the Trilogy recording sessions in Los Angeles in 1979. It was nearly 11 P.M. and the recording equipment had been shut down for the night. I was standing in the control room listening to Sinatra's friend Jilly Rizzo complain of the fever he was suffering from the shots the Sinatra group had endured for a trip the following week to Egypt, where Sinatra would give a command performance for President Anwar el-Sadat outdoors in front of the Sphinx. Assuming the recording session had ended, I was preparing to leave when suddenly I heard music coming from the studio. It was the orchestra playing the familiar introduction to "April in Paris. '' Everyone stopped what he was doing—engineers, producers, janitors, hangers-on. It appeared that the musicians, still at their places in the studio, were sight-reading the orchestration, which had been hastily distributed after the last note of "They All Laughed."

Frank Sinatra stood in front of his conductor, Billy May, and sang, unamplified and unrecorded:

I never knew the charm of spring Never met it face to face I never knew my heart could sing Never had a warm embrace, till April in Paris.

I quietly slipped into the studio so I could hear better, and caught Sinatra's eye for a second, as he continued:

Chestnuts in blossom

Holiday tables under the trees

April in Paris

This is a feeling

That no one can ever reprise.

It was a luminous performance. When he finished, we onlookers stood silently for a few seconds, unsure why Sinatra was singing "April in Paris" in a cold studio at 11 o'clock on a Wednesday night. It turned out that he planned to sing it in Egypt the following week and wanted to determine whether the key he had used for the song in 1957 was still comfortable in 1979. It was. The yearning was there.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now