Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

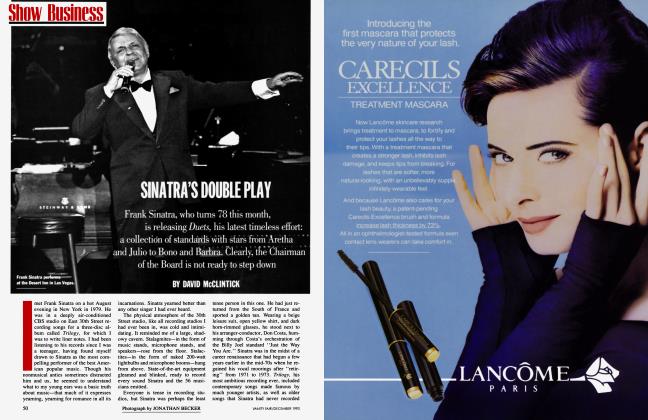

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowTHE F.B.I.'S FREEH AGENT

After the recent scandals of Waco and William Sessions, the bureau has found an old-fashioned G-man named Louis Freeh to restore its past glory

LLOYD GROVE

Dispatches

Let's go get a steam," Mike Clemente said to the kid.

As was his custom, the chunky, white-haired old mobster was holding court in the cramped locker room of the Shelton Health Center—a dingy basement gym on Livingston Street in Brooklyn. Mike Clemente had been a regular at the club for years, but the kid, a cleancut 28-year-old, was a new member. He'd only started coming in the summer of 1977, but the two had struck up a casual friendship.

He seemed like a nice kid, not like the usual rat cocksuckers that Clemente had dealt with in his long and arduous life of crime. He was quiet, intelligent, a good listener. And he showed respect. It was a fuckin' shame, Clemente thought, that with all his smarts and education the kid was having such a rough time finding gainful employment.

"You know, I'm a lawyer, but I haven't really found a job yet," he had confided to Clemente in the steam room. He seemed a lot like Clemente's grandson, who was also a lawyer—or, at least, about to graduate from law school—and was also having trouble finding a job, even though the old man had been doing his best to help.

He wished he could help the kid too.

"I got some friends here," Clemente offered—meaning the judges who liked to hang out at the Shelton Health Center when they could get away from the state courthouse around the comer. "I got a lot of friends I can introduce you to."

But the kid had never taken him up on the suggestion, as though he didn't want to put the old man to any trouble.

Mike Clemente had run into him maybe once or twice a week over the past year. The kid seemed to have a lot of time on his hands: more often than not, he'd be in the gym using the Nautilus machines or wandering between the lockers in a towel, right in the middle of the workday. The old man, of course, went to the gym not only to get a steam and rubdown (which seemed to help his bad hip), but also to do business. Business, in Clemente's case, meant collecting extortion payments in plain white envelopes from the shipping-company executives who felt the need to stay on his good side.

For Mike Clemente was the undisputed boss of the Manhattan waterfront, a capo in the Genovese crime family. No less than Carlo Gambino had attended his daughter's wedding, and Clemente had been able to place many of his own prot6g6s throughout the dock workers' union hierarchy, notably International Longshoremen's Association international vice president Anthony Scotto, a friend of then New York governor Hugh Carey, among other public officials.

Clemente was the one you had to pay if you didn't want serious shit from the I.L. A. —problems like strikes, slowdowns, possibly even broken bones. The old man found it convenient to service his clientele in the locker room or the massage room, where it was hard to conceal a government "wire"—that is, a body mike and transmitter. If you were a Mafia extortionist, you could never be too careful. Clemente knew the F.B.I. was trying to nab him—he could feel it—and there was no fuckin' way, at the age of 70, he was going to serve time again.

He was wrong. In March 1979, Mike Clemente and 11 Mob associates were indicted on 213 federal counts of racketeering, extortion, tax evasion, and other crimes. What the fuck?

Here he was, an old man with a bad hip, and now he had to appear in federal court for his arraignment. Even worse, as he waited in the back of the Manhattan courtroom, Clemente spotted the kid from the Shelton Health Center standing up front. Those stoolpigeon rat cocksuckers got him too! Hey, kid! But the kid didn't seem to see him—he was looking the other way. Clemente ordered his attorney, Paul A. Victor, to find out what the hell they were charging the kid with.

Victor walked to the front, where he saw the kid huddling with the prosecutors.

"You're an F.B.I. agent?" Victor guessed with a sinking feeling.

"Yeah," replied Special Agent Louis Freeh.

"Oh shit."

"What do you mean?"

Victor started to laugh. "Well, Mike just told me to come up here, and he insisted that I tell the prosecutor to 'let the kid go, because the kid had nothing to do with it. ' " Freeh glanced back at Clemente, who grinned and waved at him.

"I felt as low, I guess, as I could possibly feel, like a little snake," Freeh recalls. "And all during the trial Mike would sit with the defendants behind me. And once in a while, particularly when the lawyers would go off to one side to have a long discussion, he would say, 'Hey, Freeh! Let's go get a steam! Get me outta here! Get me a steam!' And I'd turn around and laugh."

Clemente was convicted of 103 counts in May 1980 and sentenced to 20 years in prison, largely on the strength of evidence gathered surreptitiously by Freeh. He had pursued Clemente and the Mob for four years, watching them from parked cars, listening to them on tapped phone lines, and, of course, taking steam baths with them. Among his fellow agents, Freeh became known as "Mad Dog," because of his perseverance and, as Special Agent Phil Deutsch remembers, because "Louie was always pissed off about something"—usually involving bureaucratic roadblocks thrown up by superiors in New York or, more often, Washington. "I really need this shit!" was Freeh's battle cry when the suits at headquarters frustrated his demands for anything from a wiretap to a search warrant.

A little more than a decade later, Louie Freeh is the new director of the F.B.I. He's gone from "Mad Dog" to top dog.

Clemente knew the F.B.I. was trying to nab him— he could feel it— and there was no fuckin' way he was going to serve time again.

" 'Mad Dog'? I don't know," Freeh says sheepishly. There's an odd smile plastered on his face, a quirkily handsome 43-year-old face framed by closecropped hair and dominated by hooded eyes and a strong, angular nose—less Efrem Zimbalist Jr. playing Inspector Lewis Erskine than Kevin Costner as Eliot Ness. "When I get my teeth into something, sometimes I don't let go," he says. "Maybe that was it."

Somehow, "Mad Dog Freeh" is hard to square with the paragon of normalcy sitting in the director's chair. Everything about Freeh says, "I am a regular guy' ' — his thick North Jersey accent (which has him referring frequently to something called "lawr enfawcement"), his badly scuffed oxfords, and his rumpled suit pants with the clunky beeper clipped artlessly to his hip (making him look like the harried manager of a Kmart).

But now he has his teeth into the world's premier law-enforcement agency, with 24,000 employees and a $2.2 billion annual budget, responsible for defending an open society from a horde of drug dealers, white-collar crooks, international spies, and foreign terrorists coming for the first time to American shores. Freeh, who has risen from F.B.I. agent to federal prosecutor to U.S. district judge, is suddenly one of the most powerful men in America: during his 10-year term, he will be able to eavesdrop on American citizens, pore over their tax returns, analyze their fingerprints and DNA, arrest them, and even invade their living rooms—as long as the constitutional niceties are observed.

The ascension of America's top G-man is an event far rarer than the inauguration of a new president, and carries with it at least as much sociopolitical mystique. The bureau, not surprisingly, has been both mythologized and demonized in the annals of Hollywood and popular culture—either as the supreme defender of the law-abiding citizenry or as the insidious enemy of individual rights and freedoms, with a penchant for knocking down doors, bugging bedrooms, and amassing scurrilous files. In the bruising months before Freeh's appointment, the luster of the F.B.I.'s carefully cultivated public image—which directors beginning with J. Edgar Hoover have gone to extraordinary lengths to mold and polish—had been considerably

f dulled. The tarnishing process began with the disastrous assault on the Branch Davidian compound in Waco, Texas, and the missteps of Travelgate, in which the nominally independent F.B.I. allowed itself to be exploited by the Clinton White House for crass political purposes. Then there was the embarrassing saga of Director William Sessions. Judge Sessions, as he liked to be called, and his meddlesome wife, Alice—a reviled figure among many F.B.I. employees who crossed her path—blundered into a series of ethical lapses involving the use of F.B.I. staffers, limousines, and other perks. The judge's stubborn refusal to leave office gracefully made him the first director in the bureau's 85-year history to be fired by a president. In addition, the F.B.I. was the target of widespread complaints about its antiquated institutional attitudes on sex and race. Morale at headquarters had seldom been lower.

Looming over everything else is the decidedly mixed legacy of J. Edgar Hoover (who served as director an astonishing 48 years), a legacy that shapes perceptions of the bureau even two decades after his death. Freeh discovers this firsthand in his first month on the job, while he is still settling into the large, charmless director's office on the seventh floor of the J. Edgar Hoover F.B.I. Building, a spectacularly ugly concrete palace that looms over Pennsylvania Avenue like one of George Orwell's sinister ministries. One morning, Freeh's secretary pokes her head into his office, interrupting an interview to announce, "It's Senator Byron Dorgan on the phone."

Continued on page 79

Continued from page 74

"Where's he from?" Freeh asks. "I never heard of him." He adds, with no particular enthusiasm, "Yeah, I'll take his call."

As he waits for the call to be transferred, Freeh peppers me with questions. "Do you know him? Is he a Democrat or a Republican? What is he calling me for?"

Dorgan, a Democrat from North Dakota, waits a decent interval after Freeh has picked up the phone before coming on the line himself—playing a time-honored Washington power game.

"How are you, sir?" Freeh begins, sitting stiffly at his desk. His respectful manner is worlds apart from the "never-heard-of-him" tone of a moment earlier.

After some small talk, including a dollop of flattery ("You're a breath of fresh air," Dorgan tells Freeh), the senator gets down to cases. Freeh listens intently.

Whatever it is Dorgan is mad about, Freeh promises to look into it. "It was terrible," the director says agreeably, "and it's a chapter that disgraces all of us."

On hanging up, Freeh declines to say what the call was about. It was, after all, a private conversation.

But at the very moment that Freeh is being so admirably discreet, Dorgan is running to the Senate floor to give the world his own detailed account of the telephone tete-^-tete. Dorgan tells the Senate that Freeh intends to apologize in the name of the F.B.I. to the family of Quentin Burdick, the recently deceased senior senator from North Dakota, for keeping a file in the 1940s and 1950s alleging that Burdick had Communist ties. The existence of the file had been revealed that morning in Roll Call, the newspaper that covers congressional affairs.

"We have got a building downtown with J. Edgar Hoover's name on it, ' ' Dorgan rails. "It ought to be taken off. ... I don't care how it is removed. I assume you can chisel it out pretty quickly."

Actually, Freeh has not agreed to apologize, let alone chisel out Hoover's name. Instead, six days later, after the Burdick file has bubbled into the sort of meaningless controversy that Washington revels in, Freeh issues a press release defending the F.B.I., praising Burdick, and blaming Roll Call for using "raw, unconfirmed data from law enforcement files."

"I say two things about Hoover," Freeh tells me. "One, without his energy and imagination, the bureau would never have been organized when it was organized, as effectively as it has been organized, and at least given the potential to do great things, which it has done over the years. On the other hand," he continues judiciously, "some of the things which he presided over and which he ordered were contrary to his obligations as director, in violation of the Constitution and all the other principles that we proceed under and respect. I also think, finally, that what he did has to be viewed in the hindsight of history. He was not the only government official at that time who was acting out of his own authority in a way that compromised the principles that were supposed to be enforced."

The ascension of America's top G-man is far rarer than the inauguration of a new president, and carries with it at least as much mystique.

While he has just been more critical of Hoover than has any previous director of the F.B.I., Freeh pronounces his verdict with the fastidious deliberation of a judge. Clearly conscious of his ancestral connection to the legendary tyrant, Freeh has recently included a critical Hoover biography in his bedside reading (though not the one containing descriptions of the director in frilly dresses). Freeh is only the fourth F.B.I. director since Hoover, who was in charge so recently that one of Freeh's drivers also chauffeured Hoover. Yet Freeh is casual about his new status, which brings with it not only a portal-to-portal government limo but also a Sabreliner jet. (These amenities certainly take the sting out of the fact that Freeh's new, $133,600 salary is an effective $9,000 pay cut from what he earned as a judge and part-time law professor at Fordham University.) He comes to the director's job with scores of longtime bureau friends, mere street agents in F.B.I. field offices, who still call him by his first name. That would have been unthinkable in Hoover's day, and also in the time of Judge Sessions and his predecessor, William Webster, another ex-jurist who preferred honorifics.

But not Freeh. "You gotta stop calling me 'Judge,' " he scolds.

) "I'm not a judge anymore. It's 'Louie.' "

From the age of 10, Louie Freeh aspired to be in the F.B.I. Unlike the dreams of most 10-yearolds, this one was not a whim. "It had to be from the media," he says, identifying the spark for his ambition. "I didn't have anybody in the family in law enforcement, so I remember Saturday-afternoon movies about the F.B.I."

Of course, it wasn't so much "the media" that captured young Louie's imagination as it was Director Hoover's tireless publicity machine—which exercised virtually total control over anything and everything that appeared about the bureau, from radio shows such as I Was a Communist for the F.B.I. to the popular TV series starring Zimbalist, which premiered on ABC in September 1965, when Louie was 15, and ran until 1974, two years after Hoover's death.

As Ronald Kessler writes in his recent book, The FBI, "Other law enforcement agencies might arrest armed and dangerous men, but only the FBI knew how to get the credit. Other law enforcement agencies had brave and effective officers, but only the FBI created an image of its agents as supermen. Others had chiefs as smart and as patriotic, but only Hoover fashioned a cult of personality with himself as symbol of truth, justice, and the American way.''

Young Louie could not have known it at the time, but Hoover and his companion, associate F.B.I. director Clyde Tolson, had long been accustomed to abusing their considerable power along with the Bill of Rights, assassinating the character of suspected "subversives" as well as collaring true criminals. No one was beyond Hoover's notice— not Martin Luther King Jr., whose extramarital flings were captured on tape recordings that were then offered to friends of the bureau in the press; not presidents, Vietnam War protesters, or ordinary citizens. Once, the F.B.I. even sent a team of agents to harass the owner of a Washington, D.C., beauty parlor who had been overheard telling a customer that Hoover was a "queer."

Rumors of cross-dressing aside, Hoover's well-documented eccentricities were ample. Former F.B.I. executive Frank Storey—who, as the Washington supervisor of the longshoremen's union case, would regularly get Agent Freeh's reports from the waterfront—recalls being warned in 1965 to make sure that his palms were wiped totally dry (Hoover couldn't tolerate clammy hands) before being ushered along with other new agents into the director's office while Tolson stood nearby. Storey recalls being terrified: "I'd heard that Tolson once had a guy booted out because, he said, 'he looks like a truck driver.' "

Still, Freeh's 74-year-old mother, Bernice, of the generation that venerated Hoover, was delighted when Time printed an illustration of her son sporting one of the snap-brim fedoras that Hoover required his agents to wear while being photographed. "I tease him and call him J. Edgar Freeh," Bernice says.

Louie was bom in Jersey City, the second of three brothers in a staunchly Catholic household, and grew up in workingclass North Bergen, a "city type of neighborhood," as Louie remembers it, in which kids played stickball in the street and engaged in minor tussles. When he was in the fourth grade at St. Joseph of the Palisades Elementary School, his teacher warned Louie's father, William, a realestate broker, "that I might be hanging around with the wrong types of boys, boys who were likely to get into trouble— 'trouble,' in those days, meaning tying somebody's shoe to the chair or something. And she sort of gave my dad some guidelines about who I should associate with and who I should not. And he strictly enforced that. There was a period of time when I was not allowed to hang around with certain kids."

Charlie gets the tailor on the side and says, 'Look, I just wanna tell you— this guy killed 13 people. Make sure he likes the suit.' "

Didn't Louie rebel against such an arbitrary restriction? "No," he says. "But it was hard to avoid them, because it was a tiny school and we'd see each other every day."

It's difficult to imagine how anyone could have worried: Louie was a devoted altar boy and future Eagle Scout, and the Christian Brothers who looked after him in high school—members of a religious teaching order who all seemed to be built like linebackers and were renowned for their bracing use of physical encouragement—seldom found it necessary to smack him in the head.

Not that Louie was without sin.

"I had a lot of scraps growing up," he insists. "And I remember getting involved with people who I thought were picking on other kids—not that I was a champion or anything, but I remember a couple of fights where I thought somebody was getting picked on. It was something that always bothered me."

Louie comes from German-Irish stock on his father's side (his paternal grandfather was a city garbage collector and later sanitation supervisor of Coney Island), and from Italian ancestry on his mother's. Bernice Chinchiolo, the daughter of immigrants, was raised in the Bronx, and her experience of discrimination—recounted to Louie one day at the kitchen table— seems to have given him his first clear sense of justice and injustice.

She told her son that in order to get a job during the Depression she had to change her name. It was an era when newspaper want ads commonly said, "Anglo-Saxon Preferred," so it was Bernice 'Chinsley" who was hired as a bookkeeper by a Wall Street brokerage house. "It just shocked me," Freeh remembers. "It made me angry. It made me a little bit embarrassed for her. So it certainly had an impact— 1 much more so, I think, than , she ever appreciated."

Through a Christian youth group in which he was a lead) er, Louie spent the summer between his junior and senior years of high school doing volunteer work in Appalachia, amid the hollows near Lancaster, Kentucky. He taught English to school-age children and toiled on a cucumber farm started by a local priest to show the inhabitants how to raise a good cash crop.

"One of the things I remember very starkly from that experience," Freeh says, "is that we did a census of the hollows—these little sort of off-theroad, off-the-mainstream places. We had a series of questions we would ask the people, and it was incredible. Many of the people did not know what country they were living in. Or they knew what country, but not what state. They had no concept—no television, no radio, no communications. We asked who the president was and some would say Franklin Roosevelt. This was in 1966."

Louie's Rutgers College roommate Greg Gaze remembers a thoughtful, self-possessed young man who went his own way. "Lou was turned more inward than outward," says Gaze, now an airforce major based in San Bernardino. He recalls how Freeh "gave me my first lesson in charity," inviting a homeless wino inside for soup and coffee. Gaze says Freeh stayed up half the night talking with the "bum"—who turned out to be a former college professor who had joined the Abraham Lincoln Battalion in the Spanish Civil War and fallen on hard times during the McCarthy era—offering him a bath and, the next morning, putting him on a bus to Princeton.

Freeh was an extremely disciplined student, a Phi Beta Kappa in American studies who managed to ignore the turmoil and temptations of campus life in the late 60s. When classes were canceled because of an anti-war protest or, say, the occupation of the administration building, Freeh went to the Manpower office downtown to earn extra money as a "temp," making deliveries from a beer truck, painting signs, or answering phones. "It was great," Freeh recalls. "When I couldn't go to school, I would just go there. Any kind of job you can imagine, I'd probably do it."

Freeh's reaction toward all the commotion at Rutgers? "It was not a hostile attitude," he says. "It was sort of an exasperation—the problem with the war and the country and the government, and everything just going down the toilet, as it seemed to be doing. And, secondly, that it was just disruptive in terms of what I was trying to do— which was get through school and go ahead with something that I wanted to do."

In June 1974 he received his law degree from Rutgers and, the following April, at age 25, was ready to enroll at the F.B.I. Academy in Quantico, Virginia. He is remembered there as an .outstanding recruit. "A quiet fellow, obviously intelligent, in excellent physical condition," says retired special agent A1 Whitaker, who served as counselor to Freeh's class during the 16-week training course at Quantico. "But I'm also remembering that he wasn't a good shot."

In the spring of 1978, the F.B.I.'s investigation of corruption on the waterfront was coming to a head. As agents fanned out from New York to Miami, Freeh and his squad in the New York field office were surveilling not only Mike Clemente in the gym but also one of Clemente's regular sources of illegal payoffs: a Brooklyn businessman named William "Sonny" Montella.

Freeh and another agent, Bob Cassidy, had spent seven months monitoring Montella through wiretaps, bugs, and visual surveillance at his marine-carpentry contracting business in Red Hook. By midMay, they had accumulated enough incriminating evidence to try to force him into becoming a "cooperating witness."

If he agreed to the deal, Montella would be a crucial witness against Clemente and union leader Tony Scotto,

among others. The government would put him and his family into the witnessprotection program, for their lives would otherwise be worthless. The agents were worried, however, that Montella's wife, Elizabeth, the daughter of the notorious mobster Joe Adonis, might resist going underground.

At about six P.M., May 17, they knocked on the door of Montella's office. For Freeh, it was the culmination of three years' work.

"Look, we're happy you're here," a prosecutor told Freeh, "but if something goes wrong, we're gonna blame the guy from New York."

' 'That was a real pressure time, ' ' Freeh recalls, "because we were confident that if we could get his attention we could convince him to cooperate. On the other hand, if we didn't, the whole house of cards was going to come down. We were prepared to make arrests in about five or six different cities, conduct dozens of searches. We had the warrants, everything was going to go down at once."

They found Montella sitting behind his desk. They identified themselves as F.B.I. Montella promptly recognized Cassidy as someone he'd had dinner with a few months before, thinking him a fellow businessman. He immediately flew into a rage. "You have the nerve to break bread with me and then come here like this?" Montella shouted at Cassidy. ' 'Fuck you! ' '

"He really was pissed off," Freeh says. "His first reaction was 'You guys are fooling me. You didn't have the bug in here.' And I said, 'Yeah, and there's the other bug right up on the ceiling.' And he started laughing, and he said, 'You'd never get past my dogs.' He had these four large attack dogs. They were half Doberman and half German shepherd. They were very vicious-type dogs, but they weren't really trained by a good trainer. So we'd started bringing them Big Macs. We'd bring them about five or six Big Macs a night, and they'd start

eating out of our hand. And pretty soon they'd see us and they'd lick us.

"So Sonny says, 'There's no way. Those dogs would have tore you to pieces.' 'No,' I said. 'Bring them in, Sonny.' He says, 'No, no, no. I couldn't bring them in.' 'Bring them in,' I said. 'We know these dogs.' So he brings the dogs in and they start licking us, and then he goes, 'Oh shit.' "

They repaired to the Opera, an Italian restaurant in Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey, where they bought Montella dinner and, over a bottle of wine, had a few laughs and closed the sale. They worked with Montella intensely for the next two years, meeting with him nearly every | day, and he became a devastatJ ing prosecution witness before disappearing into hiding. "His wife calls from time to time," Freeh says. "Once when I was on the bench, she called to say how they were doing. And they did quite /ell. He was one of the few people who continued being successful after they went into the program, because he was a good businessman."

In 1980, Freeh received a commendation from William Webster for his role in the waterfront investigation, and he was promoted and transferred down to Washington, where he was a supervisor in the organized-crime section at headquarters when he wasn't helping stage waterfront-corruption hearings for Senator Sam Nunn's Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations. He liked the subcommittee, but hated the Hoover building. He decided to quit the F.B.I.

"I was restless," he says. "It was a bureaucratic, nonoperational job, and I was very frustrated." The one good point was that he began dating Marilyn Coyle, an F.B.I. paralegal worker. "I met Marilyn in this building, somewhere on the third floor between Organized Crime and Civil Rights. And we fell right in love. And then I left, and we carried on a long-distance romance."

Freeh was hired as a prosecutor in the U.S. Attorney's Office of the Southern District of New York; Coyle soon got a job there too. (Freeh was so fastidious about not pulling strings that no one knew of their relationship until after she had snagged a job on her own.) With fellow assistant U.S. attorney Barbara Jones he successfully prosecuted mobster Benjamin "Lefty" Ruggiero and other members of the Bonanno crime family, and in due course found himself playing a leading role in one of the most complicated Mafia trials in history.

Continued on page 86

Continued from page 84

The "Pizza Connection'' case, which lasted 17 months in the courtroom of U.S. district judge Pierre Leval after an even longer investigation, unfolded an international conspiracy of Sicilian and American mafiosi to move cash, heroin, and cocaine through pizza parlors across the United States. The government, led by Louie Freeh, spent millions upon millions of dollars to prosecute Gaetano Badalamenti, the deposed head of the Sicilian Mafia, and 21 others.

One defendant was murdered in a contract killing, another was shot and wounded, and the rest save two were convicted of one serious felony or another. The case was so lengthy that by the end a member of the prosecution who had started as a paralegal had completed law school and passed the bar. For Freeh, the "Pizza" case meant the birth of two sons.

One of Freeh's star witnesses was Sicilian hit man Luigi Ronsisvalle, a government informant who had committed 13 murders in a misguided effort to become a member of the Mafia. Much to Ronsisvalle's sorrow, the Mafia wasn't interested in making him a Man of Honor. But Louie Freeh did everything he could to make his witness feel wanted.

"We needed to get Luigi ready for trial," Freeh recalls. "He was in prison, and he didn't have any clothes at all. So one day he comes into the U.S. Attorney's Office, where we were prepping him, and he says, 'Mistah Freeh! Can I get some clothes for trial?' And I said, 'Sure, we could do that.' "

F.B.I. special agent Charlie Rooney summoned a tailor from a nearby haberdashery. "So the guy comes up—a very nice fellow coming to take measurements—and Rooney pulls him aside," Freeh says. "These agents are just insufferable—they always do these things. So Charlie gets the tailor on the side and says, 'Look, I just wanna tell you—this guy killed 13 people. Make sure he likes the suit.'

"The guy is so nervous, he takes out the measuring tape and his hands are going like this." Freeh shakes his hands in mock terror. "Luigi says, 'Whatsa matta?' The guy says, 'Nothing, nothing.' He couldn't measure, his hands were shaking so much. So he suits him up, and I'll never forget, Luigi turns to me and says, 'Can I get a hat?' And I said, 'No, Luigi, you don't need a hat for trial.'

"But we always treated him with respect. We never made fun of him. We treated him as a serious fella. He was a very dangerous person. Luckily he went into the protection program after that, and he never had any problem. He ended up committing suicide, because he had these terrible memories of all the things he had done. "

In 1990, Freeh was asked by Attorney General Richard Thornburgh to lead the investigation into a crime that struck at the heart of the American judicial system: a series of letter bombs, filled with nails, had been delivered to destinations in the South, killing 11th Circuit Court of Appeals judge Robert Vance of Birmingham, Alabama, and an N.A.A.C.P. lawyer, Robert Robinson, an alderman from Savannah, Georgia.

"Louie Freeh told them, `I'm not gonna be in a beauty contest, no way!'" recounts Senator Al D'Amato.

In mid-May, when Freeh arrived in Atlanta with junior prosecutor Howard Shapiro, he found a completely stalled investigation. Competing law-enforcement agencies were fighting over jurisdiction and prime suspects, presenting contradictory evidence to different grand juries. The friction produced continual press leaks about the high-profile case, threatening the integrity of the investigation. "It was a mess," Freeh recalls, "a bureaucratic and operational disaster."

Freeh's old mentor from Quantico, A1 Whitaker, the special agent in charge of the Birmingham field office, was convinced that the bureau should concentrate on junk dealer Robert Wayne O'Ferrell, who had once owned a typewriter that matched threatening letters sent before the bombs. But Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms agent Frank Lee was just as sure that the culprit was a Georgia scam artist named Walter Leroy Moody Jr., who had been convicted 18 years earlier of possessing a homemade pipe bomb remarkably similar to one found in this case. The acrimony between the two investigative agencies was feverish.

' 'The most important day of the case, ' ' says F.B.I. Criminal Investigative Division chief Larry Potts, "was the day Louie Freeh arrived."

"People were relieved when I got down there," Freeh recalls. "As one of them said to me, 'Look, we're happy you're here, but if something goes wrong, we're gonna blame the guy from New York.' "

After a few days' review of the evidence, the guy from New York sided with Lee—and against his mentor, Whitaker. A year and two trials later, during which Freeh and Shapiro ran themselves ragged commuting home almost every weekend to spend a few hours with their families, Moody was convicted and sentenced to seven life terms, plus 400 years. Freeh was awarded the Attorney General's Award for Distinguished Service. And he has brought Shapiro to the F.B.I. as general counsel, one of the director's top advisers.

As it happens, Freeh almost didn't take the director's chair—even after meeting secretly on April 1 with White House counsel Bernard Nussbaum and Attorney General Janet Reno, and writing for Reno a memorandum detailing his plans for the F.B.I.

Nussbaum was first tipped to Freeh by two old friends, federal judges John Martin Jr. and Pierre Leval, who had presided over the Pizza Connection trial, and former U.S. attorney Robert Fiske, who got to know Freeh during the waterfront-corruption case. Freeh became the leading candidate after Travelgate made the F.B .1. 's independence from the White House a paramount issue, knocking out the favorite candidate, Richard Steams, a Massachusetts judge who had been a Rhodes scholar at Oxford with Bill Clinton. The more Nussbaum heard about Freeh—whose relative anonymity made him the darkest of dark horses—the more Freeh's stock rose. After meeting him, Reno was equally enthusiastic.

But Freeh himself was not convinced. According to Senator A1 D'Amato, the New York Republican who was Freeh's sponsor for the federal bench in 1991, the judge was wary of a White House personnel process that often seemed to resemble a meat grinder. He had just watched the public humiliation of Supreme Court hopeful Stephen Breyer, a federal judge who had been summoned to Washington from a hospital bed in Boston only to be paraded before the cameras and then denied the nomination.

"Louie Freeh told them, 'I'm not gonna be in a beauty contest, no way!' " recounts D'Amato. " 'If you resolve your problems with the present director, Sessions, and if you then decide that you want me, that's fine. But I'm not going to be in a situation where I'm competing with somebody else.' ''

"I had some conditions, " Freeh acknowledges. He insisted, for instance, that there be no leaks of his name before any final decision, lest his ability to do his job as a judge be compromised. Then, three days before he was scheduled to meet with the president, he phoned Nussbaum and told him he wasn't coming after all.

"I was so concerned about doing it over Marilyn's objections—not objections, but she was very anxious about it," Freeh says about his wife of 10 years, who was worried what the demands of the job would mean to their four sons, ages one through nine. "She was crying. She was upset. So I thought, We're not going to do this. I called Bemie and told him that. Then I told her, and she got mad at me. 'What did you call him for?' We talked about it some more and she said, 'Do it—but what happens if our family starts going to pieces?' And I said, 'I'll quit.' "

Unlike previous directors William Sessions and William Webster, who were neophytes when they took over the F.B.I., Freeh arrived in Washington knowing the bureau inside out, from its strengths as a police agency with peerless technological and investigative prowess to its not-so-obvious internal weaknesses as a federal bureaucracy hog-tied in red tape. "Do we require more than 8 percent of our agent force at headquarters when parts of the country are virtual war zones?'' he asked pointedly in his inaugural address, delivered under a blazing sun in the Hoover building's mammoth brick courtyard. The question sent a tiny shudder of apprehension through the paperpushers in the audience. "We have to be concerned about serving the law-enforcement needs of our varied communities and not focus simply on the last time the oil was changed in the bureau car.''

"What he brings from the very beginning is a very clear understanding of the judicial process, the law-enforcement process and how investigations workhow prosecutions work and how a case comes to trial," says former director Webster, now a lawyer in private practice. "I wouldn't think you'll see a lot of flamboyance, but nobody will push him around, either."

It's not just that Freeh is the first F.B.I. director in history to be regularly changing diapers, although that, too, certainly gives him a useful perspective. "We should try to follow the advice which we often give our children," he said in his inaugural speech, inveighing against interagency turf wars. "Play with your friends, be fair and honest with them, and share your toys."

"Of the five judges who have sentenced me," the convict wrote to Freeh, "you have been by far the fairest."

It was because of his decidedly unWashingtonian sense of priorities that Freeh declined the offered limo and arrived at the Hoover building on the day of his investiture behind the wheel of the family Volvo station wagon, surrounded by his wife and kids. Charlie Rooney, Freeh's old friend from the Pizza Connection case, led the way in his own Buick to the E Street entrance of F.B.I. headquarters, where a jut-jawed, spitshined agent waved him on but balked at the family in the Volvo. "Don't you have him on your list?" Rooney asked with a grin. "He's your new boss."

Purely in terms of symbolism, the manner of Louis Freeh's arrival at headquarters was a stinging rebuke to his immediate predecessor—the perquisitehappy Sessions. It's also an unmistakable message to the law-enforcement bureaucracy that things from now on will be a helluva lot different.

Freeh has been welcomed with universal praise. Indeed, talking to people about Louie Freeh is a disorienting experience. Everybody likes him, even the defense attorneys who opposed him in hardfought trials. President Clinton got a laugh at Freeh's swearing-in with the story of a convict Freeh had sentenced to 20 years in prison who had written to congratulate him on his new job. "Of the five judges who have sentenced me," the man wrote, "you have been by far the fairest."

"Louie, in a word, is a mensch," says Ivan Fisher, one of the defense lawyers in the Pizza Connection case. He is seconded by Barbara Jones. "There is nothing ambiguous about Louie Freeh," she adds. "He's the most unambiguous person you'll ever meet."

Yet, as Freeh is aware, Washington, D.C., is a world of paradox and ambiguity, in which one can sometimes be sneaky, even snakelike, in the service of a higher good. It's a city where politicians often wield power like Mafia chieftains, using many of the same methods—behavior that is not only perfectly legal but also constitutionally protected. It's a city, indeed, where the director of the F.B.I. is a politician just like any other.

But with Sessions gone, headquarters seems giddy with relief. A buttoned-down public-affairs type, discussing Freeh's worries about selling his house in the New York suburbs and buying a new one in Washington, actually jokes, "Maybe we can arrange a nice low-interest loan from Riggs"—a wildly indiscreet reference (at least for an F.B.I. agent) to the ethics violation involving Riggs National Bank, which gave Judge Sessions a below-rate mortgage.

As for repairing the F.B.I.'s battered reputation, "that's done over a period of time, but he has already done a lot, just by virtue of his being there," says Senator Sam Nunn, the influential Georgia Democrat who has admired Freeh since he worked for Nunn's Subcommittee on Investigations 13 years ago. "With his own reputation among law-enforcement people, he's already given a boost to the morale of the organization."

Meanwhile, the G-men and G-women still have a lot to learn about the differences between the new boss and the old ones. The bureau gym has gotten strangely busy at 6:30 A.M. , the unforgiving hour when Freeh stops by to suit up for his jog. "It's three times as crowded as it usually is, just because the director's there, ' ' says one agent. "I don't know what everybody thinks they're doing. He's smart enough to know they're just trying to kiss his ass."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now