Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowEditor's Letter

Russian Undressing

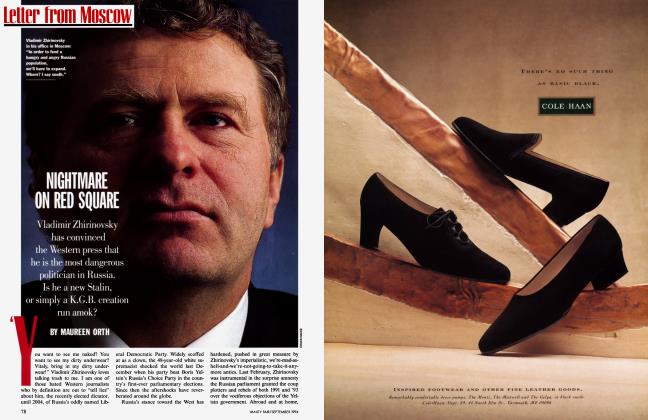

In June, The Washington Post carried a dispatch indicating that Vladimir Zhirinovsky, the fanatical leader of Russia's Liberal Democratic Party, was washedup. His party had beaten Yeltsin's in the December parliamentary elections and driven the government sharply to the right, but now his appeal was "fading in the very Russian heartland where he made his strongest showing." On its face, this was a plausible scenario: even in a country as chaotic as Russia today, how could this man, the Daffy Duck of Russian politics—a man for whom no stunt is too undignified, no statement too extreme—continue to be a serious political force? But throughout the summer, Zhirinovsky remained at the top of the news, looking dangerous on the cover of Time and undressed on the covers of the London Sunday Times Magazine and The New York Times Magazine, as journalists struggled to explain his enduring popularity. "The Western media have become Zhirinovsky's master and his slave," notes special correspondent Maureen Orth in her in-depth report ("Nightmare on Red Square") on page 78.

Though Zhirinovsky's practice of charging thousands of dollars for an interview has stymied other reporters, Orth persuaded him to give Vanity Fair free and full access; she spent many hours talking with him, as well as with his wife, his brother, and his sister. To cut through p the mysteries surrounding his background and rise to power, she combed Soviet-era archives and secret Communist Party documents. The result is a uniquely comprehensive and intimate chronicle of the creation of a political monster.

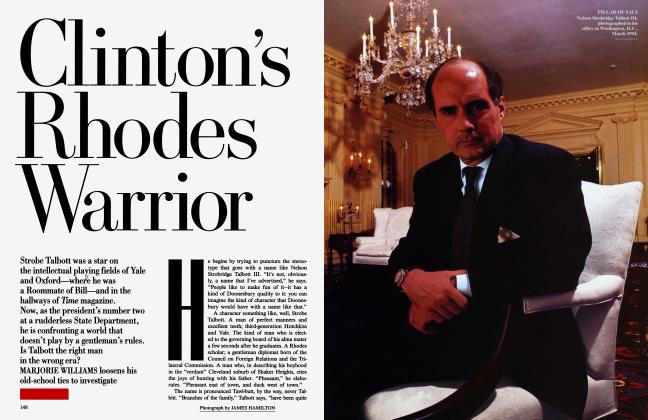

In Washington, the point man for Clinton's dealings with that monster is one of the president's closest chums, Deputy Secretary of State Strobe Talbott, who built his reputation as an expert on the Soviet Union.

In an elegant, witty profile ("Clinton's Rhodes Warrior") on page 148, contributing editor Marjorie Williams analyzes the fine line between Talbott's career as a journalist at Time and his new role as a diplomat. His star has continued to shine through the recent shake-up at the State Department, while the criticism of his boss, Secretary Warren Christopher, still comes fast and furious. But, as Williams describes Talbott, his "hallmark is the faith that almost anything can be worked out between gentlemen." And the open question is whether such a man can deal with the forces that drive a man like Vladimir Zhirinovsky.

Editor in chief

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now