Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowFOR DETAILS, SEE CREDITS PAGE

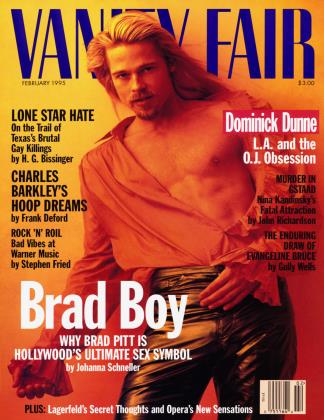

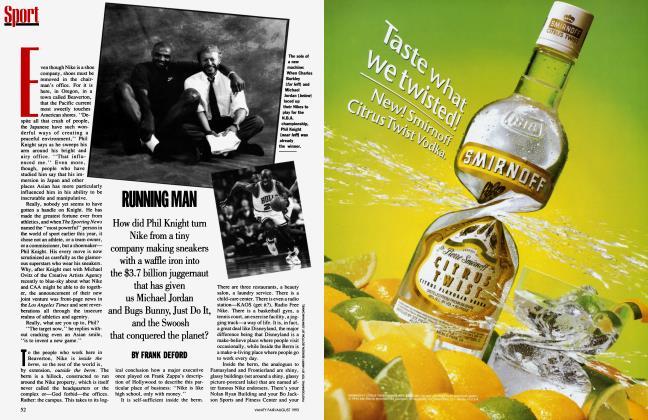

Barkley's Last Shot

FRANK DEFORD

Charles Barkley, basketball's mesmerizing, trash-talking miracle man, is bowing out; this season is his final chance for the thing that will make him whole, an N.B.A. championship for the Phoenix Suns. FRANK DEFORD explains Barkley's big bad façade, and visits with the private Charles

'It's amazing," Charles Barkley observes, reflecting upon the state of his head. He makes observations all the time, about all manner of things, alternately inducing stupefaction and fatigue from those within earshot. The Arizona Republic has even assigned a reporter to shadow Barkley on Phoenix Sun game days, solely for the purpose of recording his sundry and eclectic pronouncements in a column entitled "The Barkley Beat." Surely, in all of human history, this must be a first: having space set aside, regularly, reserved for one man's bons mots, as yet unsaid.

"Yes, it is, very amazing," Barkley goes on. Although The Arizona Republic Barkley-observation beat reporter is not on the case at this moment, Barkley is opining about how utterly fascinating it is that while white men with shaved heads invariably look pretty damned awful black men can grow even more handsome sans hair. "If I didn't shave my head I'd have a helicopter look," he reveals, "and I don't like that." I take a helicopter look to mean what was called a monk's pate in less technological times. Barkley grasps his skull tenderly, as Hamlet to Yorick, with the affection born of familiarity.

Notwithstanding his noble crown, it is Barkley's body that is truly extraordinary. Charles Barkley's body defies explanation, much as engineers concluded that a bumblebee is aerodynamical ly impossible. The National Basketball Association persists in listing him at six feet six inches, while he himself acknowledges being no more than six feet four and three-quarters— and with a weight that is a cost overrun somewhere upwards of 250. And yet, playing forward, lost in the timberland of seven-foot behemoths, he's the one who manages to grab the ball, to score. It is mystical, nearly.

Even in Barkley's first year at Auburn University, when the rival team's fans hooted and hurled pizza boxes at the chubby freshman, when he was saddled with such dreadful sobriquets as the Crisco Kid, Boy Gorge, and Food World, he somehow divined his blessing. "I knew then," he says. "I knew I could average 10 rebounds a game for the next 10 years. Wherever I played. I knew." For somehow, in the athletic vernacular, Charles Barkley "explodes." With other great basketball players, you marvel, Look at him do that! With Barkley, you wonder, How does he do that? At last, struggling, he himself is left to suggest the answer: "God is in my body."

Yet for all Barkley's personal preeminence—he was voted the league's most valuable player in 1992-93, when Michael Jordan was still gracing basketball—he has never led his team to a championship. Not in high school, not in college, not in the N.B.A. "It's not fair," says Kevin Johnson, a sage young teammate. "No one in the world is more generous than Charles, and he'll always be a great player. But if we don't win, he'll never be complete."

Of course basketball is a team game. Of course. Of course no single player—especially one so irregularly sized— can will victory for a whole team. But that is rational. That is intellectual. The rare great players whose teams do not once triumph are cruelly cursed, forever to be remembered as what the British call A Nearly Man.

The 1993-94 season was the one meant to be Phoenix's—to be Barkley's— at last. Instead, it was a desultory year for all as Barkley floundered, with injuries to both his back and knees. Despairing, he decided to quit basketball and move on to his next incarnation, which he fancies to be governor of his native Alabama—the first African-American Republican governor in history. But then, this summer, going on 32, he underwent rehabilitation for his back and decided to return for one more season, the one to remember him by.

Barkley needs a victory season all the more because he has no fond memory of a single, perfect game to embrace over time. For all the rebounds and baskets, the only game that remains in his mind, all but obsessing him, is the one a few years ago when Charles Barkley . . . spit.

The usual celebrity façade is the one by which famous people who are absolute sons of bitches in real life artfully maintain a positive image. Barkley is the reverse, the teddy bear who seeks to portray himself as a meanie. "He thinks that gives him an edge," his wife, Maureen, explains. "He thinks it intimidates people." She pauses. "I mean, off the court, too." Barkley hasn't the disposition to stay rude one-on-one, so he must be outrageous publicly. Besides, it's a profitable persona; in modern sport, ogres sell better than do all-American boys.

So, in his Nike commercials, Barkley is paired against Godzilla, monster to monster; he kills a referee in opera bouffe; more shameful yet, he growls thusly at the children of America: "I am not a role model. I am not paid to be a role model. I am paid to wreak havoc on a basketball court. Parents should be role models. Just because I can dunk a basketball doesn't mean I should raise your kids." So, when he was the host on Saturday Night Live, his opening monologue consisted of taking on Barney, the hyperlovable purple dinosaur, and mauling him (for which Maureen was all but assaulted by a mother and child at the local Toys "R" Us a few days later). So, when someone sincere in Phoenix asked Barkley what he would be doing if he didn't play basketball, he declared that he would be in "video pom." So, he calls himself a "90s nigger," infuriating whites, and praises the vision of Dan Quayle, infuriating blacks. So, when he and Maureen were separated, he enjoyed a well-publicized fling with Madonna, infuriating all God-fearing men and women of good taste. And so on and so forth.

Only occasionally does the show boil over for real. In Chicago, there was a saloon fracas. In Milwaukee, he clocked a guy who trailed him. In the first game of the Barcelona Olympics, with the whole world watching the fabled Dream Team, he gratuitously clobbered a poor, gaunt Angolan player, then compounded the assault by protesting, unrepentant: "How was I to know he wasn't carrying a spear?"

I remember chatting with Charles a couple days later, outside his hotel, and timidly venturing that he might lighten up under the glare of humankind. He snarled, "Hey, Frank, they don't like us and we don't like them." Off the court, too.

And then, one night in New Jersey, he spit. Purposely. On a fan. No matter what else, that is the moment that counts. "Don't be fooled," Maureen says. "That was a major, major, major occurrence in Charles's life. It just eats him alive. Still." That, you see, appears to be the single episode that makes Charles Barkley wonder who he really is. That is his question.

Everything else is his answers.

The private Barkley can be completely unaffected. Like our true-blue heroes are supposed to, he really does visit sick children—and without alerting the Eyewitness News mobile unit or "The Barkley Beat." He suffers fans. Even the press. "People won't believe me," says Howard White, who manages Nike's pro-basketball relations, "when I tell them Charles is one of the best people I've ever known in my life." Barkley is like one of those travel stories—with headlines such as THE NEWARK NOBODY KNOWS or SURPRISING PARAGUAY!—that no one really accepts.

The citizens of Arizona were in awe (and some fear) of Barkley's arrival in 1992, after he was traded from the Philadelphia 76ers to the Suns. But then they were shocked to discover that he just shows up places, like normal people do. The time in Barcelona when he snapped to me so bitterly about foreigners was followed soon enough by one of his famous promenades down Las Ramblas, where he kibitzed and hoisted beers with captivated fans and natives. Meanwhile, his Dream Team colleagues remained holed up in their $900-a-night rooms at their fortress hotel.

He calls himself a "90s nigger," infuriating whites, and praises the vision of Dan Quayle, infuriating blacks.

Barkley is even a dyed-in-the-wool sports fan. That may not sound surprising, but most hotshot stars really aren't into the games they don't play. Barkley knows statistics and all that stuff. "I just love sports," he gushes. "I love watching greatness." He listens to talk radio, and will call in, just like any Vinny or Bubba. On one occasion, when he heard a lady from Jersey complaining on the air about No. 34, he rang up the station, got in touch with his critic, and sent a limo, with champagne and flowers, to fetch her to his next game.

Barkley makes sense only if you appreciate that none of what has happened to him is logical. Were it not for the freak spontaneous combustion that no one has ever before found hidden in such a body, Charles Barkley would be a very fat and uneducated fellow with a helicopter top down in Leeds, Alabama, punching a time clock and offering unrestrained opinions that none of the other guys on the loading dock would pay any attention to.

Most sports superstars are so naturally brilliant that they are identified by the time they're 13 or 14. Quickly, they become spoiled little princes. But as late as his junior year in high school, Wade Barkley—they still call him by his middle name down home— was an undistinguished, overweight five-foot-ten-inch substitute on an unremarkable team. Incredibly, in barely six years, the pudgy duckling would go from being the sixthor seventh-best player at a small-town high school to being one of the six or seven best players in the world.

This is why the guffaws that have greeted Barkley's solemn pronouncement that he plans to run for governor of Alabama as early as '98 should be somewhat restrained; he has pulled off this kiss-a-frog stuff once before. Says the future candidate in his best Horatio-Alger-Meetsthe-Comeback-Kid style: "I think if you're good from the beginning it stunts your growth, your drive. Out of everything I've accomplished—everything—I still think the most important thing ever was proving everybody wrong about me. God gave me a special gift, but / have taken it a long way." Indeed, Barkley possesses such supreme confidence that by now he has faith that he can mandate victory in any basketball game. "If I'm healthy and if I can get a little he'p"—residual traces of his southern accent pop up occasionally—"I can make the play so we can win. Yes, I believe that."

Really and truly?

"I believe that so much that if we don't win when it gets to that point, I'm in shock."

Of course, as with any politician, we must be wary of Barkley's claims. He is the man, after all, who published an autobiography entitled Outrageous, and then, to prove the point, charged he had been misquoted in his own book. But someone most familiar with the high-flown Barkleyan rhetoric— Jerry Colangelo, the Suns' presidentoffers this formula: "Ninety-nine percent of the time Charles knows exactly what he's saying. Only 1 percent is he off the wall."

Whether the dream of sleeping in George Wallace's old bed is a quixotic part of that goofy 1 percent Charles or the adult version of I'll-show-theworld, Governor Barkley is still a work in progress. His platform consists of little more than ending welfare, then passing those savings along to the public schools. Despite having himself been an indifferent, even evasive student, Barkley is passionate on the subject of education. "Maybe you have to come from my background to understand how insecure a kid is if he doesn't have an education," he says, going off on something of an embryonic stump speech. "But, no, all we do is tell 'em on TV, Y'all must have a big house and a nice car and fancy clothes, and then we're surprised when they go out and try to get 'em. The first thing we've got to do in this country is find a different message to send to our kids."

Then he snorts at a favorite provision of the Congressional Black Caucus in the crime bill. "Thirty million into midnight basketball—that's a Band-Aid on a bullet wound. The real criminals aren't gonna be playin' any basketball come midnight. Why don't they take that $30 million and put it into scholarships?"

Barkley can be a master of flamboyance, but as a novice candidate, if only because he is still feeling his way, he is more studied and earnest, more . . . political. "I guarantee you there won't be a boy or girl who wouldn't take a scholarship if they gave it to him. I give out three scholarships myself, and they're all academic. Not athletic. I'm just so sick of athletics and blacks." His voice rises. He's growing more animated, on more familiar ground. "All you ever hear is we run for 1,000 yards and we dunk. You make 20 points, you get 10 rebounds, they'll find you. Oh, they'll come and find you. But you make straight A's in the same school, they don't even know you're there. And that's sad. That's very sad about this country."

But if his politics are mostly only emotional so far, and his deportment tends to the radical, he certainly is a Republican, culturally and fiscally conservative. For example, his controversial I'm-no-role-model Nike commercial—which he proposed himself— brought down a firestorm of criticism that he was selfish and irresponsible. His prime nemesis in Philadelphia, Stan Hochman of the Daily News, labeled it "despicable." Barkley, though, remains proud and faithful to the message, which he sees as pro-family. His point is that athletes are not surrogates, just celebrities; parents themselves must assume responsibility.

The chairman of the Republican National Committee, Haley Barbour, professes to be intrigued by a Barkley candidacy. He cites new congressman Sonny Bono and former congressman Fred Grandy, late of The Love Boat, as Republicans who were taken seriously by the voters despite their having matriculated in politics from a weightless professional past. "I mean, Grandy played a stooge, really," Barbour says. And, of course, how can the party forget that a somewhat more serious actor became president, while a former football player may well be the next G.O.R standard-bearer.

Barkley's color is likewise appealing for Republican cross-casting. Says Armstrong Williams, the black conservative writer and radio host of The Right Side, "We have to start somewhere convincing African-Americans to get off the Democratic plantation, and how better to do it than with someone like Charles with a high profile?"

Besides, Barkley is every bit a Republican, well, fat cat. Barkley's mother in 1988: "But, Charles, Bush will only work for the rich people." Barkley: "But, Mom, I am rich." He earns $8million-plus in salary and endorsements, resides in some of the best suburbs in America, possesses all the finest accoutrements, including a Japanese Lexus and an American Ford Bronco, and plays golf with other squires at the nation's most exclusive country clubs.

Apart from alighting from a golf cart to take about 85 to 90 swings a round, Barkley faithfully subscribes to that dictum of another maverick capitalist, the late Henry Ford, who declared, "Exercise is bunk. If you are healthy you don't need it, if you are sick you shouldn't take it." Most players dutifully work out in the off-season, but, in basketball parlance, Barkley is an old 31, his back buckled from the years of fat and lazy summers, then of lugging his avoirdupois at warp speed across the hardwood.

In the late 1980s, as his 76er team began to erode around him, Barkley took a lot of heat from the famously vituperative Philadelphia sports press. "Philadelphia is not a good place to lose," he intones, more didactically than mournfully. By 1991, Barkley was so frustrated in the City of Brotherly Love that he openly petitioned other teams to trade for him. He took to brooding at home. His marriage grew brittle, then shattered. In Leeds, his younger brother Darryl had had drug-related problems with the law, and Barkley felt his fame had belittled and tormented his brother.

Everywhere, too, he began to hear the whispers that he would never quite succeed. He couldn't win in high school, he couldn't win in college, and . . . "Somewhere along the way I got lost," he says now upon reflection. "I let people convince me that I'm nothing if I don't win a championship. If I believe that, I'm stupid. But"—a sigh—"I believed it."

His back began to bother him more. He railed publicly against his teammates. In one silly wrangle, he even got himself in trouble with the league for joking about betting on his own games. It was getting harder and harder to be Charles Barkley. And finally, one night on the road, playing against the woeful New Jersey Nets, it happened. The 76ers struggled; the cries against No. 34 rained down. When the Nets tied the score, Barkley turned to the crowd. He spit. Purposely. He spit on a fan. A little eight-year-old girl.

Although Barkley is sometimes unfairly tagged with an uncomplimentary epithet relating to the area of the central derrière, it is altogether accurate to describe him as anal. This prissy fellow even makes up his bed in hotels, and wherever he lives—Phoenix in season, Philadelphia in summer, Alabama on visits—"I just walk around the house looking for dirty stuff." Maureen reports that after a game, at three or four in the morning, she has heard Charles vacuuming downstairs, or awoken to see him zealously Windexing the mirrors that line the long hallway from their bedroom.

This house, which was Charles's bachelor abode, lies just outside Philadelphia, on the Main Line, surrounded by Tudor and fieldstone mansions and tony schools and seminaries. The two commercial establishments closest to the Barkleys are Lord and Taylor and Saks. But just beyond them is the typical franchise effluvia: a 7-Eleven, a Midas, a Holiday Inn, and the Friday's where the famous basketball player first spied the gorgeous blonde. Charles and Maureen were wed in 1989, and their daughter, Christiana, was bom later that year.

Continued on page 146

"I give out three scholarships, all academic. Not atliletic. I'm just so sick of athletics and blacks.

Continued from page 126

Within the sports world, checkerboard romances and marriages are casually accepted for what they largely are: the natural result of geography and economic class. Black athletes move to upscale white neighborhoods wherein reside white women. Of course, abroad in the land, the Barkleys attract more notice as an interracial couple, even a threatening call from some ugly Klansman on a recent visit back to Alabama. And not long after Charles spit on the little white girl, a man came up to Maureen, called her "nigger lover," and spit in her face.

Both the Barkleys say, though, that the O. J. Simpson case has failed to produce more unwarranted attention. "The only people who ever seem to be upset,"

Maureen says, "are black women and white men. I tell the men:

Look, if I hadn't married Charles I certainly never would have married you anyway, so, really, don't worry about it."

Barkley does cry race occasionally when he's railing about some injustice, and, in a different vein, he enjoys teasing his deficient Caucasian co-stars, rivals and teammates, for suffering from the dreaded "white man's disease." But, he declares, "really, I transcend color. I'm not pro-black. In fact, I think it's even worse for black people to be racist."

In his office hangout across the hall from the kitchen, Charles clicks over from CNN to Oprah. He perks up: the theme of today's show is things you want your spouse to learn. One of the guests would like her husband to learn to dance. Exactly what Charles wants of his wife! "Mo, Mo, quick, come in here," he hollers. The couple on Oprah starts to dance. But it's not at all what Charles expected. In fact, it is ... a fox-trot. Maureen arrives. "I don't believe this," Charles says, as if he had stumbled on some strange tribal rite on the Discovery Channel.

"But, Charles, this is how white people dance," Maureen explains. He shakes his head in wonder. Evidently, his transcendence of race is not quite complete.

Maureen returns to the kitchen, to peel potatoes. This is not unusual. Charles thinks of potatoes as a genuine vegetable, e.g., "The only vegetables I eat are creamed com and potatoes." Maybe that is why his body is different from everybody else's in the human race, because he does not eat green vegetables. Wouldn't that be a kick? All over America mothers would say, Eat your creamed com and potatoes so you can grow up as big and strong and fast as Charles Barkley.

The only game that remains in his mind, all but obsessing him, is the one when Charles Barkley... spit

Maureen peels some more faux vegetables. Different as she and her husband may be—the poor little black boy from Leeds, Alabama, who was deserted by his father, to be raised by his mother and grandmother, and the prosperous white girl from a big, happy, traditional Catholic family in Bucks County, Pennsylvania— they share one common fundamental. Just as everybody put him down for being fat, everybody kidded her for being a hopelessly skinny twig with big, funny feet. But then he grew up to be Charles Barkley, and she grew up to be a beautiful, willowy woman who dared marry a famous black man named Charles Barkley.

"Whatever problems we've had, color was never an issue," Maureen says. "I promise you that. Never."

He takes all the blame for the separation, I tell her.

"Oh. What does he say?"

I look at my notes and read them to her. "I like to be alone, and the only place I can be alone is at home. They won't let me be alone anywhere else. And that alienated Maureen." I look up; she nods. "Because I needed to have peace and quiet at home. She was there, but I needed to be by myself. And then we weren't winning, and I started to rebel at her. I take all the blame."

She smiles softly. "That's very nice of Charles to take the responsibility for our troubles, but I'm sure I nagged him some. He does have mood swings, and I didn't know how to deal with that then. But I understand him wanting to be by himself. I do. / value being by myself."

They've been back together for more than a year now and want to have another child, but Maureen thinks they should wait till this last season—the quest—is over. "It's just so different being a celebrity," she says. "You can't even imagine till you live with one." It's probably hardest of all being a famous athlete. Most of the entertainment people cluster together in L.A. and New York. A Philadelphia or a Phoenix, a Dallas, an Atlanta—big as they are, when it comes to famous people, all they have is their home-team sports stars. Theirs. "People expect so much of you," Maureen goes on. "It's amazing to me that Charles copes so beautifully."

Except for that one night, anyway. At the New Jersey Meadowlands in '91. And the heckler was screaming, down by the court, shouting the foulest vulgarities right into Barkley's face. And the Nets' free throw went in, and the man screamed again at him. And Barkley broke. He turned and lunged at the man, spitting at him. Then, satisfied, he raced downcourt. He didn't know that he'd missed the heckler, and, instead, his spittle had flown into the face of a little girl named Lauren Rose.

As soon as he found out what had happened, Barkley called Lauren, apologizing. Without telling anyone, he bought season tickets for the Roses, and he escorted Lauren and her family to a fancy charity dinner. But that was all for Lauren. What about Barkley?

"I look back and I think, Well, the worst case would be if I spit and hit a

little girl," he says. "So, I was unlucky. All right? And the best case—the very best case—is I spit and hit the asshole screaming at me. But you see—no."

No?

"No, there is no best case, because what does that say about me, that I let a basketball game—a game!—get to me so much that I want to spit on any other human being? It was my fault. It was me. It was all me." He pauses, then sighs. "After that I started to become a better person."

Tt's lunchtime at the Barkleys'. Charles JLhas already been to the gym for his daily rehab. He's only 10 pounds over his target weight, and, dutifully, he restricts himself to a dry turkey sandwich with Evian. He clicks on the TV in his office. His favorite soap, All My Children, is over, but the U.S. Open tennis is on. "Hey, Pete Sampras," Barkley calls out with utter delight. Sampras is far and away the best player in the world, at the height of his powers. "Look at him!" Barkley coos. And: "Whatta serve!" And: "Amazing!"

But Sampras is performing with none of the enthusiasm that Barkley displays watching him. His only manifest reaction to even his most spectacular shots is to drop his head over his racket and study the strings. "What is the matter with him?" Barkley finally inquires. Sampras hits a glorious winner, only to return, head bowed, to the baseline. "What is the matter with someone like that?" Barkley asks again, only louder now. "He should be the happiest person in the world. But look at him. Sampras!" He fairly wails at the television screen. "Sampras!"

Sampras remains deeply involved with his stupid strings. "He's No. 1, the best there is," Barkley goes on. "In the world. Isn't that amazing?"

I remind Barkley that he's the best in the world at what he does.

"It's just such a great feeling to be able to entertain people," he says. "You get to bring such joy. But look at him." Sampras mopes about, unwilling to acknowledge his gift to the crowd.

Barkley shakes his head. "Why?" he asks. "No. 1. It's the greatest time of your life. You get to do what you want. The people come to see you. Now, when you're through playing, nobody will care then. Nobody will pay to see you. Nobody. Not anymore. You can sleep as late as you want then. Nobody cares." He leans forward in his big leather chair.

"I never forget," he announces. "The best way to keep people away from you is not to be good at anything. There's so many people who could be good, could be great, if they tried. Derrick Coleman [of the New Jersey Nets] should be the best player in the world. Some people are scared to risk it, though. Me, I say, If you're scared, buy a dog."

He flicks the remote control, relentlessly moving onward. He is just plain fed up with Pete Sampras. Soon, Barkley will be departing for Phoenix, for the season of his posterity, his last chance at completeness as a player. He is putting the best face on it, of course, but I believe him when he swears he is secure enough to suffer another year without a championship. "All I ever wanted was 10 good years," he says. "I accomplished everything I set out to do in basketball. Be a good player, do the best I possibly could, and make a good living so I could take care of my mother and grandmother."

Downstairs, the garage door opens. Barkley's daughter, Christiana, is back. She has been a bad girl all day, and she knows it, but her mother lets her enjoy a brief amnesty. She runs to her father. Christiana is precocious and pretty in pigtails, her shade (as you would expect) exactly midway between the pale cream of her mother and the cool beurre noir of her father. He rocks her back and forth in his arms.

For an instant, I can see the same scene taking place next June in a locker room as Phoenix celebrates its championship. Or maybe I can even visualize this tableau a few years from now, on Election Night in Montgomery, Alabama.

Or none of the above.

After all, it is enough that right now Christiana Barkley is in the arms of her role model.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now