Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

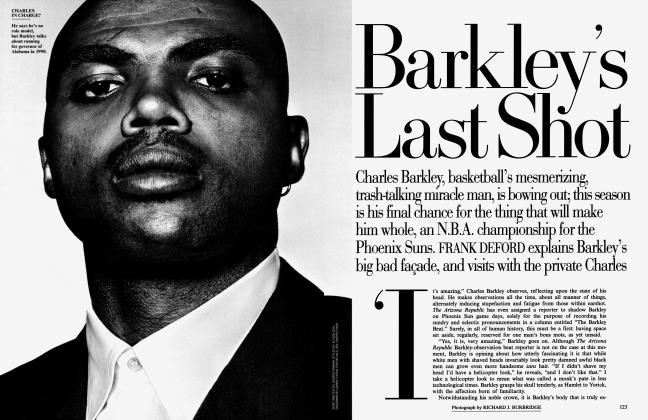

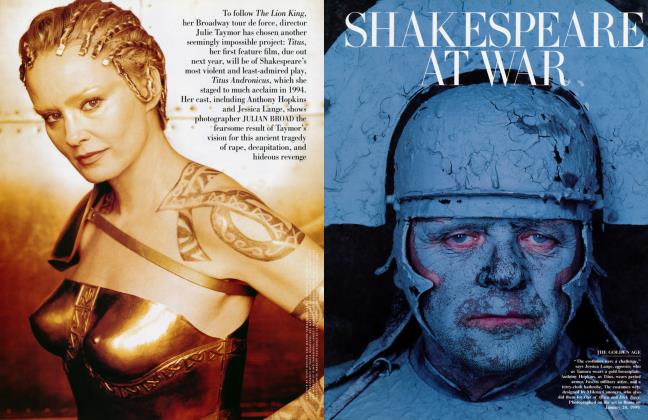

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowEvangeline Bell Bruce, widow of one of America's greatest modern diplomats, is the last of a quietly powerful breed of Washington hostess. But her flawless style masks family tragedy—and her deep commitment to the shelter for runaways she helped establish in memory of her daughter, whose violent death remains unsolved. GULLY WELLS obtains a rare audience as the publication of Bruce's first book reveals another facet of Georgetown's reticent empress.

February 1995 Gully WellsEvangeline Bell Bruce, widow of one of America's greatest modern diplomats, is the last of a quietly powerful breed of Washington hostess. But her flawless style masks family tragedy—and her deep commitment to the shelter for runaways she helped establish in memory of her daughter, whose violent death remains unsolved. GULLY WELLS obtains a rare audience as the publication of Bruce's first book reveals another facet of Georgetown's reticent empress.

February 1995 Gully WellsIt is Sunday in Georgetown, and Evangeline Bruce is at home for a few invited friends and guests. In one corner of the small drawing room off the hallway, where silver trays of freshly shucked oysters are set out on a white linen tablecloth, Vernon Jordan, the lawyer-lobbyist, stands sipping a bullshot and talking to Washington Post publishing executive Katharine Graham. To their right, a few steps flow gracefully into a much larger room, where sunlight streams through tall windows hung with apple-green silk-taffeta curtains, and David Brinkley, still in his full Sunday-morning TV makeup, chats with Arianna Stassinopoulos Huffington, author and wife of Congressman Michael Huffington. Nearby, Lord Weidenfeld, the London publisher, discusses recent events in England with Lucia Flecha de Lima, the wife of the Brazilian ambassador to the United States and close friend of the Princess of Wales. Across the room, the artist Polly Kraft, who is married to Lloyd Cutler, the former special counsel to President Clinton, and journalist Michael Kinsley are deep in discussion. Maids in starched aprons move among the guests with trays of miniature steak-tartare sandwiches and the famous Bruce bacon (unfailingly crisp, sweet, and greaseless), while off to one side a distinguished-looking waiter carves paper-thin slices of smoked salmon and lays them on tiny triangles of buttered brown bread. The hostess, wearing a bright tweed suit, its cut and color more Paris than London, briefly joins Ronald Steel, the historian, on an oversize striped sofa. Behind them, Ambassador Paulo-Tarso Flecha de Lima and Jennifer Phillips, the wife of the president of the board of trustees of the Phillips Collection, listen to political commentator Elizabeth Drew speak about her new book, On the Edge. Fragments of these conversations float above the crackle of the birchwood fire on the warm, narcissus-scented air, guests come and go, maids pour more champagne, and one has the agreeable certainty that this is the place to be on this particular Sunday in Georgetown.

Indeed, for the better part of half a century, Evangeline Bruce has quietly held her place at the epicenter of the world of the influential, the intellectual, and the wealthy of the nation's capital. Her role in Washington, however, is not easy to define. Put crudely, she is a player, and has remained one even though her husband, the distinguished American diplomat David K. E. Bruce, died nearly 20 years ago. In addition to being one of the legendary Georgetown hostesses, she has also helped create a shelter for runaway kids, and her first book, Napoleon and Josephine: An Improbable Marriage, will be published by Scribner next month. As the writer Sally Quinn, her Georgetown neighbor, says, "If Washington were the Sistine Chapel, Evangeline would be up there on the ceiling." Katharine Graham sums her up in two words: enchantress and seductress.

David Bruce, who worked for every president from Harry Truman to Gerald Ford, was one of the Wise Men, the group who directed American foreign policy in the crucial post-World War II era. The only ambassador ever to serve in London, Paris, and Bonn, Bruce was once described by Henry Kissinger as "one of our ablest ambassadors and most distinguished public figures." "I know it's a tired old cliche," Evangeline told me, "but we were partners in every sense of the word. For instance, from day one in Paris, David expected me to be solely responsible for all the diplomatic entertaining, which forced me to get over my shyness." After the ambassador died in 1977, Jacqueline Onassis wrote to his widow and referred to the "bright path you cut through an age where so few people have grace and imagination and the virtues of another time. . . . One was so proud as an American to think that other countries recognized you as our very best."

"Things are so gray now. There's grandeur about Evangeline that is missing in the current scene."

"Grace" and "the virtues of another time" might suggest a prissy, old-fashioned quality, but that would be very far off the mark. Friends of Evangeline Bruce, who is now in her 70s, continually describe her as "girlish" and "flirtatious" and even "eccentric." None of them ever fails to mention her extraordinary beauty. "Of course, her face is her misfortune," Sir Isaiah Berlin once said, and he was only half joking. Great beauty tends to intimidate people; they don't know how to deal with it easily. In Evangeline's case, it is the kind of perfectly structured beauty—the cheekbones, the elongated limbs, the slender hands, the impossibly long neck—that works with every era, age, and fashion. And her sense of style is unerring. "She never throws anything away, and will mix a new Donna Karan jacket with some old Balenciaga lace stretch pants and look sensational," says Polly Kraft.

"The first time I saw her," says Evan Thomas, Newsweek's Washington-bureau chief and co-author of The Wise Men, "she was at a party, wearing a camisole top, which looked to me like the most beautiful underwear I'd ever seen. She was standing next to former secretary of the navy Paul Nitze, and there they both were, flirting in a way that I thought people had forgotten all about. I was dazzled. She is from an earlier Washington era. From a time when people actually had fun, something they seem to have forgotten all about. Things are so gray and cautious now. There's a kind of grandeur about Evangeline Bruce that is missing in the current scene."

Her grandeur has sometimes been mistakenly interpreted as hauteur or even coldness. The historian Arthur Schlesinger Jr., who was at Harvard in the late 30s, when "a beautiful young girl named Evangeline Bell" was at Radcliffe, and who is still one of her closest friends, admits that there are "great areas of privacy" that surround her, and that there has always been "a line that one doesn't cross." According to Ronald Steel, what may appear to be froideur is in fact shyness: "She is a retiring person who prefers asking questions to making pronouncements." Notoriously reticent about herself and what she is up to, she belongs to that generation—and class—whose members were brought up never to toot their own horn, or even talk about themselves. That explains, perhaps, why so many of her oldest and dearest friends knew almost nothing about her forthcoming book. "Everyone thought that it must be some demented fantasy," says British journalist Alexander Chancellor, snorting with laughter. "Nobody believed that she was actually writing it."

"One was so proud as an American," Jacqueline Onassis wrote, "to think that other countries recognized you as our very best."

"If I'd had any sense at all, I'd never have chosen the most controversial and written-about period in French history," Evangeline Bruce confessed to me with a smile. The book's provenance actually stretches back to another book she wrote, 20 years ago, about the characters and events of a pivotal year in the French Revolution, 1795. For various reasons, including a period of devastating upheaval and tragedy in her private life, the earlier book was never published, but most of the material has found its way into Napoleon and Josephine. "I have always been fascinated by France, and especially by the revolutionary era," she continued, "and was sent to French schools until I went to Radcliffe."

Evangeline had a peripatetic childhood. Her father, Edward Bell, was an American diplomat, and when she was small the family lived in China and Japan. "Almost the only thing I can remember about China is my nanny taking me for walks along the Great Wall in Beijing, and I was terribly disappointed when I went back there in the 70s to find that the part we used to march along was no longer standing." Her father died when she was still very young, and her mother married the British diplomat Sir James Dodds. "We lived in just about every country you can imagine," she told me. "Italy, Sweden, France, China, Holland, Britain, and Switzerland." After Radcliffe, where she studied Chinese history and French literature, France came back into her life again, in the late 40s, when her husband, David Bruce, was sent there first to oversee the Marshall Plan, Secretary of State George C. Marshall's program for the reconstruction of Europe after World War II, and later to be the American ambassador.

U.S. foreign policy in the postwar era was controlled by a group of men who constituted, in the late Joseph Alsop's memorable phrase, the Wasp Ascendancy. They included John J. McCloy, Averell Harriman, Dean Acheson, George Kennan, Charles Bohlen, and David Bruce, and they served America at a time when the country seemed invincible. "This group was running the world. They had the kind of confidence that came not only from America's being in charge," says Evan Thomas, "but also from their own sense of social position, and, in Bruce's case, from his great charm, intelligence, and presence."

America's first priority then was to help rebuild Europe, to make economic prosperity its shield against Communism. Out of the Marshall Plan eventually came the idea of the European Community, and the two French statesmen who were most instrumental in formulating the concept of European unity were Robert Schuman, the French foreign minister, and Jean Monnet, the French political economist who became the first president of the European Coal and Steel Community's High Authority. Their objective was to bind France and Germany together, in Schuman's words, "in an embrace so close that neither could draw back far enough to hit the other." Encouraged by David Bruce, both men were frequent visitors at the American Embassy, where, Evangeline remarked, "the initial meetings took place between Schuman, [U.S. secretary of state] Dean Acheson, and, of course, the patron saint, Monnet. . . . You could almost say that the idea was born in that residence."

If, as Lady Eden, the wife of British prime minister Sir Anthony Eden, once said, at the height of the Suez Crisis in 1956, she felt as though "the Suez Canal was flowing through the drawing room," then the Bruces must have seen the Loire and the Rhine gurgling past the wood paneling of the American residence on the Avenue d'lena. "David was instrumental in getting the United States government to give its support to the European community," says Arthur Hartman, who worked for Bruce during that period and went on to be the American ambassador in Paris and Moscow. "The unusual thing about David was that when he had a problem he'd fly straight to Washington, get the government together, and get from them the decision he wanted. I never knew another ambassador who was quite that active in formulating policy."

The ambassador's wife was just as busy. With three children under the age of seven—Alexandra (known as Sasha), David, and Nicholas—the juggling act wasn't always easy. "I was terrified that I wasn't doing everything right," Evangeline confesses now. "Whatever I was doing, I felt guilty. I had to get to my desk by eight if I was ever to get the day's work done." There, with the help of her staff, she dealt with correspondence, organized the household, and planned the guest lists and menus for dinners, lunches, and receptions. In addition to gallery openings and evenings at the theater, ballet, and opera, there were shooting weekends with President Vincent Auriol at Rambouillet and cozier escapes to Mouton, Philippe and Pauline de Rothschild's chateau north of Bordeaux. "How hard an Ambassador's wife has to work if she is doing her job," Susan Mary Alsop wrote in a letter to Marietta Tree of their mutual friend in 1951. "[Evangeline is] out every night or entertaining . . . and I know that it weighs on her if the three cocktail parties she is quite likely to have to attend of an evening prevent her from the storytelling hour before [the children] go to bed."

After the long years of war and occupation, French society had rebounded with a manic vengeance. There were parties galore, many of them elaborate costume affairs, including the opulent 1900 party given in January 1951 by Marie-Laure de Noailles, the Parisian arts patron, which Susan Mary Alsop described in another letter: "Evangeline Bruce is eight months pregnant and despite it looked sensationally beautiful the other night. [The] Bruces . . . made a superb entree. . . . Evangeline cast as a Toulouse-Lautrec bookkeeper, wearing a high red wig, a boned collar and a voluminous black dress. David, unrecognizable in a black wig and thickest black mustache."

"Guilt, guilt, guilt is my recollection of every job, except for Germany, where I had a bit more time for the children."

For the weekends that weren't spent with friends or away on official business, there was a small but exquisite pavilion in the park at Versailles that had been lent to the Bruces by a grateful French government. With its echoes of Marie Antoinette and the Petit Trianon, here they could escape the relentless social life, be with the children, and indulge in their shared passion for 18th-century French history and art.

"It is the period, with all its vertiginous swings, that has always attracted me," Evangeline Bruce explained, sitting back on a sofa in my living room and crossing her legs. She was dressed in a soft, gray pinstriped suit, the jacket perfectly tailored and the skirt just above the knee. It seemed very subdued until I noticed the stockings: sheer, black, with seams. The pencil-thin black line up the back only elongated her legs, which are of Dietrich proportions, and that, of course, was the whole point. "It was as chaotic as our own, with a fascinating cast of characters," she continued. "There is not one action, not one piece of foreign or domestic policy, no military campaign of Napoleon's, which is not controversial and has not been scrutinized by historians of varying political tendencies. Fashions have changed with each regime. Napoleon is such a protean figure—however do you evaluate him? And Josephine's biographers have undergone similar swings. Her reputation has veered between Madonna and courtesan, with remarkably little in between."

Like Bruce herself, her book combines scholarship with verve and originality. As London editor Christopher Falkus wrote in a report for George Weidenfeld, who will publish the book in England this summer, "Her tone is basically cool and factual, with plenty of pace as well. She does not overwrite but is never dull. . . . Although the subject has been covered in many books, hers has somehow managed to remain 'fresh' throughout."

After Paris came a succession of equally dazzling posts. David Bruce happened to be a Democrat, but no matter who was in the White House, he was always needed. In Bonn he was able to further the European community's cause through his close friendship with Chancellor Konrad Adenauer, and later in London, where he served from 1961 to 1969—longer than any other American ambassador—he developed close ties with both the Labour and Conservative governments. Quite apart from his intellect and diplomatic skills, he had a sense of humor that seduced everyone, including John F. Kennedy. Bruce's cables, "written in longhand in an almost Jeffersonian style," according to former ambassador Hartman, were legendary in the Kennedy White House. Katharine Graham remembers being at a party on a boat with President Kennedy when he read one of them out loud. "He was laughing, because David always jazzed up these official reports with funny asides and gossip." The quality of the gossip from London improved dramatically when the details of the affair involving War Secretary John Profumo and Christine Keeler started seeping out in 1963. Call girls, Russian agents, government ministers—all described in Bruce's inimitable style—it was just the kind of scandal that J.F.K. relished.

London was, if possible, even more frenetic for the ambassador's wife. Apart from her official duties, Evangeline always had a life of her own, which encompassed an eclectic mix of people-young writers, theater directors, painters, dress designers. "She knew a lot of people that most ambassadors' wives would never have met," says George Weidenfeld. This was the 60s, after all, when London was in a state of mind-bending iconoclastic flux. It was also the Vietnam era, a tricky time to be representing the American government and its policies abroad. There were huge demonstrations outside the embassy in Grosvenor Square, and even friends' behavior could be, well, unpredictable. Once, when the critic Kenneth Tynan and his wife Kathleen were invited to dinner, Kathleen courageously scrawled her own, very individual protest in lipstick all over the mirror in the ladies' room of the embassy. This was also the time when women with any pretensions to being au courant (and whose figures weren't total disaster areas) were busy unburdening themselves of their bras, but only if they could pass the pencil test: Take off your bra and place a pencil under your breast. If it stays there by itself, put your bra back on. If it falls to the ground, you can face the world with impunity, and without a bra. Evangeline's postcard to the friend who had told her about the trick said merely, "The pencil dropped!"

The embassy pace was relentless. "Guilt, guilt, guilt is my recollection of every job, except for Germany, where I had a bit more time for the children," she says today. David and Sasha were soon sent home to boarding schools in America. Nicholas stayed in London until he was 14 years old; then he too was sent to St. Paul's. According to Arthur Hartman, "There were always nurses or governesses around, as well as the constant going out at night. I guess you could say it was more in the British tradition." David Bruce was already nearing his 50s when the first of his children was born, and although his devotion to them was unquestionable, he wasn't the kind of father who felt the need to involve himself in every detail of their daily lives. It is impossible to imagine this very civilized gentleman fitting a drooling baby in a Snugli over his Savile Row suit, or playing catch on the green velvet lawn behind the ambassador's residence.

The Bruces never lost their close connection with London. In 1970 they moved to a set of chambers in the famously elegant 18th-century Albany building on Piccadilly, where Lord Byron had lived and where their neighbors included the actor Terence Stamp and Edward Heath before he became prime minister. Evangeline has kept the apartment, and spends a part of each year there.

David and Evangeline Bruce were, by any standards, a gilded couple. Born in 1898, David was descended from a distinguished Scottish family who had settled in Virginia long before the Revolution. His father was a senator from Maryland, and David belonged to that fortunate group of Americans—immortalized by F. Scott Fitzgerald, a Princeton classmate—who had had the good sense to be born into just the right families in just the right country at just the right time. In 1926 he married Ailsa Mellon, the only daughter of Andrew W. Mellon, the Pittsburgh industrialist, who was then secretary of the Treasury. President Coolidge was among the guests at thenelaborate wedding. Mellon, who thought his son-in-law was brilliant and always had enormous respect for him, gave him for his wedding present $1 million, which, cleverly invested, became the basis of the Bruce family fortune. Although the marriage did not last, Bruce's friendship with the Mellons did, and through them he entered the world of high finance. He became director of 25 corporations, including Union Pacific, Alcoa, and Pan American Airways. When Andrew Mellon created the National Gallery of Art in Washington, David Bruce became its first president.

"If Washington were the Sistine Chapel, Evangeline would be up there on the ceiling," says Sally Quinn.

When war broke out in Europe, Bruce was an outspoken proponent of American involvement. Since he was determined to work in public service, William "Wild Bill" Donovan, the founder of the O.S.S., precursor of the C.I.A., not only offered him a job in 1941 but also assumed the role of accidental matchmaker. "I met Donovan when I was in Washington during the war," Evangeline remembered. "He suggested that I work for the O.S.S." In 1942 she was sent to London, where her boss turned out to be a tall and alarmingly attractive Virginian. The postscript to this part of the story takes place many years later, when America was in the hysterical grip of the Clarence Thomas/Anita Hill show. President Bush found himself next to Evangeline Bruce at dinner and asked if she had ever suffered the horrendous indignity of being sexually harassed in the workplace. "But of course I have," she replied brightly. "By David Bruce."

After London came Paris in 1948, then back to Washington in '52, then Bonn in '57, then London in '61, then Paris again for the Vietnam peace talks in '70, and then Beijing in '73. Bruce was the first U.S. envoy to China after Nixon's breakthrough visit. In 1974, when he was in his 70s, he went to Brussels as ambassador to NATO.

This was a grim time for the Bruces. Their daughter, Sasha, whose life had become more and more fractured over the years, seemed close to despair. "It was a depressing time with Sasha," her mother remembers. "That was when Sasha kept arriving in Brussels and spending awful nights." Despite the young woman's enormous charm, intelligence, and beauty, the demons inside her head had started to take over. She became increasingly volatile, and there was a nihilistic aspect to her that was reflected in her questionable choice of men, culminating in her disastrous marriage.

Marios Michaelides was nobody's idea of a suitable husband. He had met Sasha in Greece in 1974 and almost immediately set out to gain control over her, isolating her from her friends and family, abusing her mentally and physically, and finally perhaps even murdering her. Sasha was found at the Bruce-family estate, Staunton Hill, in Virginia on November 7, 1975, suffering from a gunshot wound to the head. She died two days later. Whose finger, hers or her husband's, was on the trigger was never conclusively established, and at the request of her father there was no autopsy. At first her death was ruled a suicide. According to Susan Mary Alsop, "I don't think they know to this day whether she killed herself or was murdered." But in 1978 the investigation was reopened, and Michaelides was charged with murder. He was also indicted for stealing quantities of paintings, antique furniture, and family silver from Staunton Hill. He had returned to Athens several months earlier, and has always denied all charges against him. As a Greek national, he is exempt from extradition under the provisions of a treaty between the United States and Greece.

"David called me from the State Department to tell me about Sasha," Susan Mary Alsop remembers, "and asked me to meet Evangeline at the airport when she arrived from Brussels. She was extraordinarily in control of herself, very calm and pale. There was a small plane waiting to fly her to Staunton Hill."

The death shattered the family, and brought with it the added pain of publicity and gossip. Many of David Bruce's closest friends believe that he never really recovered from the tragedy; he died two years later at the age of 79. In the wake of Sasha's death, her mother had to endure the loss of her husband, added to which there were the newspaper and magazine stories, a book, and a ceaseless rumor mill churning out lurid accounts of Sasha's troubled relationships with men and with her family. "A great many people in Washington thought that Evangeline had not been a very good mother," Susan Mary Alsop recalls. "They claimed that she had been preoccupied with her duties and that she had been too close to her husband. I completely disagree with that. I thought that she was a most devoted mother, and I wrote to the editor of The Washington Post in response to some terrible article after Sasha's death. I carried the letter down to the Post myself to make sure that it arrived."

Even today, there is a kind of collective Schadenfreude among people who knew the family but not very well. It's as though the world couldn't wait for the carapace of perfection to be cracked. Connie Bruce, a cousin by marriage, says about Evangeline, "She gets a bad rap for not being a family person. But she holds the whole extended family together at Thanksgiving and at Christmas."

"When Sasha was at Radcliffe, she worked in a program that helped troubled young people," Evangeline explained to me. "And so, when I got back from Brussels, the first thing I did was to see if there was any similar kind of place that needed help." The place she found happened to be in her own backyard—almost. What was to become the Sasha Bruce Youthwork had started out in 1974 as an outreach program for street kids run out of a church basement near Dupont Circle. After the project was officially organized in 1977, it continued to grow, and today it runs 12 programs, 5 of them residential. There are two apartment buildings and one group home in addition to Sasha Bruce House, a big old brick Edwardian pile that is open 24 hours a day, 365 days a year. "It is the only temporary shelter in Washington where kids can just walk in off the street," says Deborah Shore, the director of the program, which employs a full-time staff of 100 and an additional 150 volunteers. City and federal grants supply 75 percent of the operating costs, and private donations amount to $650,000 annually.

Evangeline has involved many of her friends in raising money for the Sasha Bruce Youthwork; even the British and French Embassies have been roped in for gala evenings and movie screenings. "It is the focus of her life," Tommy Bruce, a cousin, explained to me over lunch in Georgetown. He is on the board, as are Susan Mary Alsop and Vernon Jordan's wife, Ann. Neither David nor Nicholas Bruce is involved. Both of Evangeline's sons have moved away from the Washington world of their parents. David lives with his wife and baby daughter at Staunton Hill, the Gothic Revival plantation house his father once filled with antiques and paintings and famous collections of rare books and vintage wines. All those have now disappeared; some were allegedly stolen by Marios Michaelides, the rest were sold by David, who runs the estate as a conference center and bed-and-breakfast. "It's almost as if he wanted to exorcise the place," Tommy Bruce said. Nicholas Bruce lives quietly in a house deep in the Pennsylvania countryside, "doing his own thing," in his cousin Tommy's words.

The two brothers rarely see each other.

After the deaths of their husbands within a few years of each other, Evangeline and her old friend Marietta Tree set up house together every summer in the hills of Tuscany. According to Lord Jenkins, the chancellor of the Exchequer in Harold Wilson's Labour government and now chancellor of Oxford University, the two women "complemented each other perfectly" as hostesses to their shared circle of transatlantic friends. Since Marietta's death in 1991, Evangeline has continued the tradition in Provence, where she is joined by those closest to her, including Sir Nicholas Henderson, the British diplomat, and his wife, Arthur and Alexandra Schlesinger, and the novelist Edna O'Brien. She has never remarried, although her name was romantically linked to at least one man, the late William Paley, after the death of his wife Babe.

"Evangeline's in a sphere where she can do anything she wants," says Sally Quinn. "It's all part of the legend." And yet what she has chosen to do isn't easy. At an age when she might be excused from putting herself on the line, she has finished writing an intellectually demanding book, she helps run the memorial to her daughter, and she's still up there on Washington's "Sistine Chapel ceiling." Elegant. Elusive. Evanescent. As we sat together at our last meeting, talking about Napoleon's life, I reminded her of what he told his biographer just before he died: "You should slide over the weak parts." What, I asked, would she say to her biographer? "My weak parts?" She replied without skipping a beat. "When the children were young, that's probably the weakest. The guilt and the strain." Just for a moment the perfectly proportioned Gainsborough face looked wistful, even sad. But then it was time to go. The chauffeur was waiting downstairs, but the plane she had to catch wouldn't.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now