Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowLINCOLN MEMORIAL

New York City Ballet co-founder Lincoln Kirstein put his fortune, his Rolodex, and his imagination in service to the dance

DAVID DANIEL

Pnslsrrinl

By the time I met Lincoln Kirstein, in 1986, I knew his story like I knew the Lord's Prayer or the Pledge of Allegiance. He'd been given several million dollars in 1930 when he was 23. In those days that was a lot of money. He used his trust fund, his imagination, his social connections (and the mother of all Rolodexes) to

bring George Balanchine to America, co-found the School of American Ballet and the New York City Ballet, and help establish Lincoln Center, the Museum of Modern Art, and the Dance Collection of the New York Public Library. The list goes on.

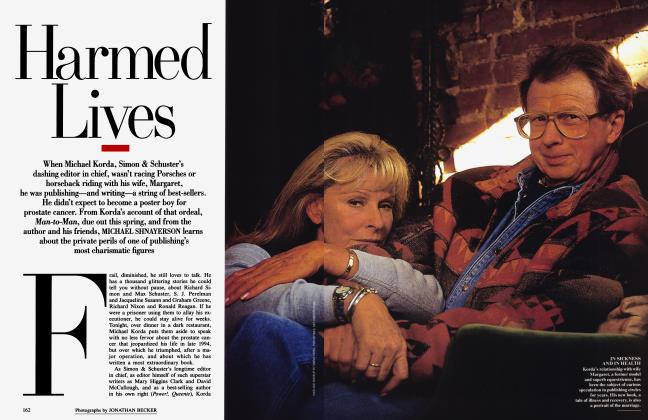

His public philanthropies are not just well recorded; they're the main chapter of American cultural history in this century. Yet there is a side of him that is noted mainly in affectionate gos-

sip. Hardly anyone knows about the stained-glass artist whose entire career consisted of a yearly commission from Kirstein, the Harlem church that he refurbished and maintained, the penniless writers who received much-needed rent checks from him, or the people whose projects he deemed hopeless but supported anyway.

I knew him by sight long before I knew who he was. I began attending New York City Ballet performances in the mid-1960s, shortly after the company moved to the New York State Theater at Lincoln Center. My music student's allowance permitted me to buy tickets only at the very top of the house—standing room in the fifth ring, for 75 cents. I soon learned, however, that two of the best seats (A 116 and A117, on the aisle, front row of the first ring) were always open. So by the time the lights had dimmed for the second ballet, I'd slip in and watch Suzanne Farrell in luxury. I wasn't the only one who upgraded to first class: there was a tall man in a black suit, with close-cropped hair and a permanent scowl, who also came to the first ring to find a seat after the house had darkened. But since I was already in the best one, he'd sit quietly on the steps beside my chair.

Later that season I saw him at the bar during an intermission and pointed him out to a friend, who explained, "That's Lincoln Kirstein!" Those seats were perpetually reserved for him. And though he never asked me to move, I never sat there again. And I certainly didn't bring it up when I finally met him some 20 years later and he invited me to his house on 19th Street. "Come on in and let's drink a few bottles of wine," he said. And we did. He showed me many of his paintings and sculptures, then took me upstairs, where he had converted a large room into a studio for a young painter he'd taken under his wing. "Do you know what a portrait is?" he growled. Without waiting for me to think of an answer, he replied, "It's a painting in which there's something wrong with the mouth."

As I was walking down the hallway to leave, he told me that he had outlived all his family. Then he said, "Now I have more money than I could spend in three lifetimes. It's wonderful. I wish everyone could be rich."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now