Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowTHE GOLD DIGGERS

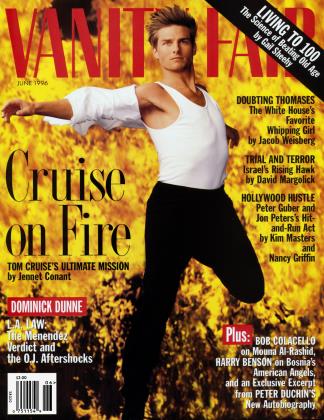

KIM MASTERS

NANCY GRIFFIN

Hollywood was floored by the $3.4 billion hole left in Sony by producers Jon Peters and Peter Guber. But, as a new book shows, the high-profile team that took credit for Batman and Rain Man had a history of financial hit-and-runs

Hollywood

ACT I MEETING CUTE

As the late 70s faded, Jon Peters and Barbra Streisand were part of a rich, successful Malibu crowd which included Neil Bogart, the flamboyant founder of Casablanca Records. Peters and Streisand owned a house across the street from Bogart's in the Colony, a very private, guarded enclave at the edge of the Pacific where stars including Cher, Linda Ronstadt, and Johnny Carson also owned homes.

Peters was the last of a breed: a streetsavvy showman who had made it in show business by breaking all the rules. In the mid-70s he had ended his reign as the owner of the hottest hair salon in Beverly Hills, having moved from serving as Streisand's hairdresser and lover to working as her manager and producing partner. "In those days, people thought Jon was a gigolo," says his friend Geraldo Rivera.

Peters had clawed his way up. His mother was born into an Italian hairdressing clan, the Paganos. His father, Jack Peters, was three-quarters Cherokee and owned a diner in Hollywood. One afternoon when Peters was 10, his dad drove home from work in his Studebaker, walked in the front door, slumped down in his favorite chair, and died of a heart attack. "It was like my world kind of ended," says Peters.

He dropped out of school in the seventh grade and went into the family business. While still a teenager, he dyed prostitutes' pubic hair to match their poodles in New York City and later styled wealthy heiresses in Philadelphia. After returning to Los Angeles, he opened his own salons and found entree into the entertainment world when he married the young actress Lesley Ann Warren. They divorced after he met Streisand.

His proving ground was co-producing A Star Is Born featuring Streisand, who starred in the smash Warner Bros, musical with Kris Kristofferson. Peters was so invested in the movie, which he considered the story of his life with Streisand, that he briefly considered casting himself as his lady's leading man—an idea scotched only after he warbled a pitiful rendition of Don't Be Cruel for Jerry Schatzberg, the director then attached to the project. "I was offkey the entire time, admits Peters. "I figured, 'Fuck it, I'll try anything. . . . ' Whatever sticks I'll do." When Peters told Warner's executive Frank Wells that he had decided not to act in the film, "Frank gave me a kiss and said, 'Thank God! Thank God!' "

Excerpted from Hit and Run: How Jon Peters and Peter Guber Took Sony for a Ride in Hollywood, by Nancy Griffin and Kim Masters, to be published in June by Simon & Schuster; © 1996 by the authors.

that before I knew her Peter Guber would call and talk dirty to her on the phone," says Jon Peters.

As a novice producer, however, Peters scored some remarkable coups. He had gotten Warner's to allow Streisand to film and record a live concert before a crowd of 60,000 extras in Tempe, Arizona, instead of lip-synching and faking the concert with footage from Woodstock. Most important, he had spearheaded the film's landmark marketing campaign, featuring a Francesco Scavullo photo of Streisand and Kristofferson in a semi-nude embrace. "Jon wanted to push the envelope at every corner," recalls one Warner's executive. A Star Is Born was the prototypical Jon Peters project, a volatile production punctuated by curses, violent arguments, numerous firings, and explosive battles with director Frank Pierson and Streisand. At the end of a tense shooting day in which Streisand filmed a hot-tub love scene with Kristofferson, the jealous Peters chased his girlfriend around the Warner's lot until she found a ride home. During another quarrel, while the two were driving to a meeting, Peters—with his left hand on the wheel—reached over and grabbed his lover, ripping her blouse off. She swung her leg up and pressed a stilettoed heel into his neck as he sped down the Hollywood Freeway, struggling to maintain control. The film that emerged from this ferment was panned by critics but remains the biggest hit of StreiI sand's career. It grossed more than $90 million.

Having defied the odds, Peters was weighing his next move. On the strength of his relationship with Streisand, he had made a production deal with Orion Pictures; the three-picture pact stipulated that she was to appear in at least one of his films. Streisand was obsessed with "Yentl, the Yeshiva Boy," by Isaac Bashevis Singer, the story of a Jewish girl in Poland who poses as a boy in order to study the Talmud. Peters loathed the project—a period piece with distinctly nonrock music. He tried to bully her out of making the film. "Barbra, you have one year left before you turn into an old bag," he yelled one night in front of friends. She started to cry, but proceeded to strike out on her own. The new producer needed a new alliance.

Peters sometimes strolled the beach with Neil Bogart, who occasionally started their walks with a couple of quaaludes. A hard-living former New Yorker whose Rolls-Royce bore the license PS80 BRONX, Bogart had made his fortune by virtually inventing bubblegum music. After that genre faded, he started Casablanca Records, hitting pay dirt with a former gospel singer living in Germany named Donna Summer. Soon he was looking to buy himself a piece of the film industry. As luck would have it, his friend Peter Guber was just then beginning to make a name for himself as a producer.

Guber was a fast-talking, highly educated lawyer from Boston who had risen swiftly in the Columbia Pictures hierarchy. Dubbed "the Kid" by his mentor, producer Ray Stark, Guber had been made head of production by the age of 29. Now an independent producer, he had a film called The Deep, starring Jacqueline Bisset, in production. The picture would be a $100 million hit, though Bogart couldn't have known that when he merged Casablanca with Guber's production company, FilmWorks, in November 1976. To some observers, it seemed that Bogart hadn't gotten much of a bargain. "What Neil wanted more than anything was to get into the movie business and he was willing to pay anything," says producer Rob Cohen, who made Thank God It's Friday at Casablanca.

Guber and Bogart soon found themselves a new, deep-pocketed partner. PolyGram International, a straitlaced GermanDutch joint venture, wanted to branch out from classical music. At a glance, PolyGram seemed to be getting a good deal when it paid between $10 million and $15 million for nearly half of Casablanca Records and FilmWorks in 1977.

At the Casablanca offices on Sunset Boulevard, twin stuffed camels greeted visitors in the lobby. "We had this interior decorator spending a million dollars a year on furniture," says Jeff Wald, who was Donna Summer's manager. "You walked into Casablanca and the size of the speakers just assaulted your senses, and there was cocaine on people's desks. And by the time we got down to business, it was almost irrelevant."

But business was never irrelevant to Guber, who kept his distance from these high jinks. Always cautious and comparatively conservative, he nevertheless seemed entirely at home with Bogart's nonpharmaceutical excesses and did nothing to check the company's profligacy. After scoring two box-office hits with successful sound tracks—T.G.I.F. and Midnight Express—he let film production languish. As Casablanca Records hemorrhaged money, Bogart's drug abuse became more of an issue. By early 1980, PolyGram had decided that Bogart had to go. It was an agonizing moment for Guber. He adored Bogart. But he made the sensible decision and dumped his partner. PolyGram agreed to invest $100 million to finance Guber's new film company, PolyGram Pictures.

Although better acquainted with Bogart, Peters naturally had crossed paths with Guber. Streisand had told him that Guber had tried to cultivate a relationship with her when he was a junior executive at Columbia, where she made Funny Girl. "Barbra told me that before I knew her Peter would call her late at night and talk dirty to her on the phone," Peters says. (Guber's habit of speaking to women, even in business meetings, in the most graphic sexual terms would persist in the years ahead.) When Peters linked up with Streisand, he approached Guber, then still at Columbia, and pitched his first solo production, The Eyes of Laura Mars. Guber dismissed him. "Jon Peters is a hairdresserhe declared.

Guber would weave a web around these guys and convince them that everything wasO.K.... He was a wonderful illusionist."

But now Guber needed to replace Bogart with another partner whose personality would energize and camouflage him. Meanwhile, as Peters pondered his future without Streisand, he and Bogart's pal became better acquainted at parties held at Guber's house on Brownwood Place in Bel Air. Friends noticed the two men circling each other in a kind of courtship. "You could see them falling in love, saying to each other, 'Aren't we incredibly rich and entrepreneurial?' " says one guest. Guber's wife, Lynda, encouraged it. She wanted her husband to find someone to help him scale the heights of Hollywood.

In May 1980, Jon Peters, Peter Guber, and Neil Bogart formed Boardwalk, a new company. Bogart would do music and Peters would make movies. Guber would lend his name while remaining chief executive at PolyGram Pictures. He could assuage his guilt over breaking up with Bogart, who had been diagnosed with cancer, while creating an escape hatch from PolyGram.

Guber started to spend PolyGram's money with abandon, while constantly seeking to sweeten his deal. "There was a permanent renegotiation of his contract or his perks or whatever that drove us crazy," says Eckart Haas, PolyGram's former C.E.O. "There was hardly any particular business deal which didn't somehow result in a discussion of his own contract." Guber's producing fee soared above the industry norm; reportedly he also received a high percentage of the box-office gross.

An executive at Universal, which distributed PolyGram films, sums up the Guber modus operandi; "Find a company, move in, make it his own, and move

out. ... He departs, having used that company to make movies with his name on them." Yet Guber persuaded PolyGram that he felt a responsibility to its business. "Peter would weave a web around these guys and convince them that everything was O.K., even when they were looking at the numbers, seeing that it wasn't," says an executive formerly affiliated with Guber. "He was a wonderful illusionist." (Guber has repeatedly declined to be interviewed.)

As it turned out, Guber didn't flee to Boardwalk; instead, Peters joined PolyGram. "Guber forced Jon into the picture," says PolyGram's Haas. "Peter said, 'Either you agree that he comes in or I commit suicide, jump out the window,' or whatever. It was a power sell." Guber gave his new partner half of his 50 percent stake in PolyGram's film company and jettisoned Boardwalk. On his own again, Bogart managed to score one last hit, Joan Jett's "I Love Rock 'n' Roll," before he died in May 1982.

Guber and Peters soon became so close that Lynda began to feel left out. At PolyGram "they sat together at a long glass desk, working the phones," says Hillary Ripps, Peters's former assistant. "They really liked to be around each other." Some sensed a homoerotic current in their relationship. (Peters recalls that years later in a joint therapy session Guber would declare, "I love you. No, I don't love you—I feel like I'm in love with you.")

But the rush was not about sex. "Money is their drug," says an associate. "Money and power." In the movie business, neither could be obtained without muscle—which Peters could supply for both of them. Says Rob Cohen, "Jon completed Peter. If you can have your alter ego destroy everything in your path so that you can walk in on rose petals, that's a great thing."

Together, Guber and Peters shoved a half-dozen projects into the PolyGram pipeline. Because they split a fee for every movie produced, it was in their interest to start as many movies as possible.

"It doesn't matter if the movies make any money," Peters told his former assistant Laura Ziskin. "We make a fortune."

Peters became the dominant force, assuming the bad-cop role for the nonconfrontational Guber. When creative executive Barry Beckerman dared to contradict Guber, Peters flew to the rescue. "You can't talk to my partner that way!" he shouted. The next day, Beckerman found a dozen bottles of organic shampoo on his desk—a peace offering.

But war was flaring on another front. "We had a string of pictures that fell on their ass," says former PolyGram Pictures C.O.O. Gordon Stulberg. Early releases bombed—including King of the Mountain, with Harry Hamlin, and Endless Love, starring Brooke Shields. In July 1981, Guber and Peters attempted some spin.

"We're just trying to have some fun and make the days enjoyable," Guber blithely told the Los Angeles Times. "We've made people hundreds of i millions of dollars ( in revenue."

PolyGram knew otherwise. The GuberPeters slate was awash in red ink. An American Werewolf in London and Missing would become modest successes, but they could not compensate for the other pictures or the fact that Guber sold Flashdance to Paramount, letting a blockbuster slip away. PolyGram had had enough. In January 1982, the company pulled the plug, having reportedly poured $100 million into its film division.

Guber and Peters established their own company and briefly alighted at Universal, but it didn't last. That studio's new chief, Frank Price, was wise to their ways. "This was a hostile environment," observes a former Universal executive. "It was time to find a new host body."

Luckily, in 1982, Barry Beckerman had taken a script for a film version of Batman over to Warner Bros., where Jon Peters had old friends. "Not only do they want Batman," Beckerman told Guber and Peters, "they want everything else we have, too."

ACT II

PLAYING THE GAME

After PolyGram, Peter Guber's marriage hit a rough patch and the producer rented a house by himself in the Colony. "He was a mess emotionally," says a friend. The couple reconciled—but only after Guber paid a visit to his lawyer. "He was told he would have to give her half his assets," says a source who was in the room when Guber returned. "He called up Lynda and said, 'Hi, honey. I'm coming home.'"

After his split with Streisand, Jon Peters romanced Christine Forsyth, a blonde interior designer, whom he would marry. But they kept breaking up, and Peters—who had started dating at age 10—was rarely lonely. Says producer Polly Platt, "Somehow in childhood, Jon's survival must have depended on the love of women, and did he ever learn how to get it." The pattern always seemed the same: he set his sights and overwhelmed his quarry, sending huge flower arrangements and starting his beloved on a regime of buttocks exercises. "Every woman," Peters advised, "needs help there."

In a therapy session with Peters, Guber declared, "I don't love youI feel like I'm in love with you."

Episodes of ballistic anger continued. In 1985, two landscapers went to Peters's Aspen ranch to collect $110 which they were owed. "Peters came out wearing a bathrobe and carrying an old-style, pearl-handled six-shooter," says police officer Tom Stephenson. "He proceeded to point it at them, yelling and screaming." The men sued for $22 million, saying that Peters had squeezed the trigger four times. He settled out of court, reportedly for $60,000.

At Warner's, Peters and Guber set up shop in Building 66 on the Burbank lot, where Jon's pal Terry Semel, Warner's president and C.O.O., occupied a corner office. Their first project at Warner's was Vision Quest, with Matthew Modine. As he had learned to do on A Star Is Born, Peters focused on producing a hit sound track. He and music producer Phil Ramone had heard about a virtually unknown singer-dancer from New York who had signed a deal with Sire Records, a Warner's subsidiary. Ramone invited the singer, named Madonna, to Streisand's house on Carolwood Drive in Beverly Hills. She played some of her European videos. The group was impressed, and Madonna recorded "Crazy for You" for Vision Quest.

As it happened, the movie's release coincided with the debut of Madonna's Like a Virgin album. Warner Records chief Mo Ostin didn't want "Crazy for You" released as a single; it would distract attention from the album. Ostin asked Warner's C.E.O. Bob Daly to pull the Madonna track. Daly summoned Peters and Guber and relayed the news. As Guber watched in horror, Peters leapt on top of Daly's desk—and began jumping up and down in protest. Daly ran from the room. But Warner's eventually caved, and such incidents only enlarged the Peters legend.

The team flourished. "A lot of people get paralyzed in the decision-making process," says Roger Birnbaum, who was president of the Guber-Peters company in 1986. "They didn't." Guber stayed in the office working the phones. He grew a ponytail and cut a slick figure in his designer suits and white socks with soft loafers. He made endless lists on yellow legal pads and spouted maxims. "The perception of power" is what matters, he said. "People move toward power."

Peters worked at home, taking meetings in Bermuda shorts by his pool. Says screenwriter Andrew Smith, "When he picks up the phone, it's like some guy from the neighborhood—you know, it's 'Hey, sweetie, how ya doooo-in?' That's how he talks. There's a sweetness to him. He's always doing that 'heeeey,' and he's pinching and kissing."

Too voracious to settle for being merely producers, Guber and Peters were determined to have their own studio one day. Generally, however, the less Guber and Peters had to do with the actual making of their movies, the more they liked it. They hired executives to oversee script development and outside producers to make the movies. Adept at marketing, they were not so much filmmakers as entrepreneurs who owned a film-producing company. "They were never on the set, they were never in the cutting room," says Steven Spielberg, director of The Color Purple, a film for which Guber and Peters received executive-producer credits—basically for buying the rights to the novel.

Peters and Guber fueled their rise at Warner's by stroking executives who helped them advance and neutralizing those who didn't. Mark Rosenberg, a former left-wing activist, had been named president of production in July 1983, as Guber and Peters arrived. Intellectual by Hollywood standards, he had pushed serious projects such as The Killing Fields, which dealt with the Khmer Rouge's genocidal reign in Cambodia.

Other executives had far more patience for Peters and Guber, namely Jon's former aide Mark Canton, a senior vice president who wanted Rosenberg's job. Unlike Rosenberg, Canton wasn't concerned about killing fields. A sign on his door announced that a "Friend of Comedy" dwelled therein. Some observers added the phrase "Enemy of Intelligence" when they described the sign to friends.

The engagement party Peters threw at his Beverly Hills mansion for Canton and his fiancee, Wendy Finerman, in 1985 was surreal. "Like Tara in the middle of Beverly Hills," recalled one invitee. A chimpanzee in a Warner's T-shirt was perched on a tree branch. An orangutan sat in a wheelchair. Then a portentous incident occurred. Surrounded by a crowd of people, including Daly and Semel, who were sipping wine around the pool, Mark Rosenberg fell into the water. It was especially embarrassing for Rosenberg, who was overweight.

"Mark fell in the pool! Mark fell in the pool!" cried Peters and Canton, jumping up and down. "For the next several days, everyone talked about it," says another source. "It was really revolting." But on S pers announced Warner Bros.' promotion of Mark Canton to president of worldwide theatrical production. Rosenberg died in 1992.

Peters overwhelmed women, always starting his beloved on a regime of buttocks exercises.

Guber and Peters, however, were up to their old tricks, honing the "hit and run" financial practices which had served them so well at PolyGram. Guber, particularly, was forever on the lookout to save money—for himself. By the mid-80s, he and Peters had deals all over town. (They had a housekeeping deal with Warner's for Batman and other projects, but were free to develop ideas elsewhere.) Although such arrangements are routinely exploited by producers, Guber turned it into an art form. He asked his secretary to tell a printer that he would not pay for the programs for his daughter's Bas Mitzvah until the bill was resubmitted with the notation "for scripts printed." First-class plane tickets were billed to more than one studio. But by far his most ingenious scheme involved the financing of his boat.

In 1982, Guber had purchased an 80foot steel ketch, made in New Zealand, which he transformed into a luxury yacht and filmmaking vessel. No expense was spared on The Oz. Angelo Donghia, the interior designer of the S.S. France, decorated it with Picasso ceramics and George Hurrell portraits. A hot tub was built on the ship's fantail. At the same time, the motor sailer was outfitted to serve as a high-tech filmmaking platform.

Guber used The Oz for family-vacation cruises in the Caribbean and to Hawaii, but also made the boat earn its keep. "We did a fair amount of corporate entertaining," says captain John Bill. In L.A., The Oz was docked at Marina Del Rey, and it was rented out for private charters and to film and commercial productions. By registering The Oz as a charter vehicle, Guber could write off renovations and operating costs.

In 1984, Guber and Peters launched a television division, teaming up with Centerpoint, a company headed by Tom Tannenbaum. He had raised $100 million from Wisconsin-based Sentry Insurance, whose chief, Bill Ellis, wanted to get into Hollywood.

For Centerpoint, the Guber-Peters company produced an NBC series called Dreams, which was quickly canceled. They also made a TV movie starring Mr. T that went $1 million over budget, an extraordinary overrun. Then Guber came up with Ocean Quest, a series which amounted to filming blonde "personality" Shawn Weatherly in a bikini sailing around the world on The Oz.

Guber sold his friend Brandon Tartikoff, then president of NBC, six hours of Ocean Quest for a $600,000an-hour licensing fee. The going rate was $800,000; it was a bargain for the powerful Tartikoff. Ocean Quest, however, cost $875,000 per episode, and Centerpoint had to kick in the additional $275,000 per show.

The Oz was chartered by Centerpoint for the better part of the year that the series was being filmed, from 1984 to 1985. Guber would fly in occasionally to meet Weatherly and crew, joining them in La Paz for a Mexican episode and in Cuba, where he was received by Castro.

"Ocean Quest cost a fortune," admits Tom Tannenbaum, who says he wasn't sure that Sentry Insurance understood the kind of deficits that were involved in financing the program. "They were an insurance company from Wisconsin," he says.

Ocean Quest premiered on NBC in September 1985 and ultimately put Centerpoint out of business. Sentry Insurance lost millions on its investment. Others fared better. "Peter told me GuberPeters made a lot of money in Centerpoint," says Tannenbaum. In 1987, Guber sold The Oz for $1 million.

ACT III

WITCHES

As they climbed the ladder of success, Guber and Peters developed a reputation for going to any length to get material they wanted, even if it meant grabbing properties from others.

Filmmaker Rob Cohen first heard about The Witches of Eastwick during a 1983 dinner with his friend Don Devlin, who thought Jack Nicholson might be interested in starring in a film based on the John Updike novel. Cohen came up with an idea for adapting the book into a film, and pitched it to Guber at a breakfast meeting. "I love witches," Guber declared. He sent Cohen to Mark Canton at Warner's, who was also a booster. Then Cohen called the agent handling film rights, hoping to lock up the property. He was informed that Guber had just optioned the book for $50,000.

"They bought the book out from under me," says Cohen. "I went over to Guber's office and he presented a deal to us which was essentially a line producer's deal." Guber and Peters would get a producing fee of as much as $750,000, while Cohen and Devlin would split $250,000 for the grunt work of making the movie.

A year later, Cohen sent screenwriter Michael Cristofer's first draft of the screenplay to Nicholson. "If we can get the right director, I'm in," the star said. George Miller, director of the Mad Maxi Road Warrior trilogy, was interested, too, and Cohen and Devlin passed the word to Warner's and to Guber and Peters. Days later, Cohen heard from Cristofer. "When are you going to Paris?" the screenwriter asked. "I just got a call from Lucy Fisher at Warner's, and she said I'm supposed to go to Paris and meet George Miller."

Fisher told Cohen that Warner's had decided to send Guber to close the deal. She added that Cohen would get a call shortly from Warner's business-affairs director, Jim Miller, about changing his and Devlin's credit on the film from producers to executive producers, a hollow title. Now that Witches of Eastwick had attracted big-name talent, Guber and Peters were shoving Cohen and Devlin aside. Mark Canton's brother, Neil Canton, was hired as line producer.

The production got off to a rocky start when Warner's pressured George Miller, who had promised the lead role of Alexandra to Susan Sarandon, into replacing her with Cher. Miller asked Sarandon to play the number-two witch, Jane. Michelle Pfeiffer would be witch number three. Sarandon got the impression that Cher had demanded the lead role. "Susan wouldn't talk to me, she wouldn't look at me, she was crying a lot, she was smoking like crazy," Cher says. "I thought it was just erratic behavior."

Miller was just as resentful. "George Miller wanted anybody but me in that movie," Cher says. "Like, on my birthday," she continues. "I'll never forget this. We've got a picture of me in my hotel room on my bed: they're bringing a cake in to me, and I'm sitting there crying because George Miller told me I'm not sexy enough to play Alexandra."

Other conflicts erupted. Miller envisioned the film as "an ironic, eccentric comedy of manners." Jon Peters, whom Miller describes as "genuinely thoughtdisordered," demanded a special-effects extravaganza. Warner's let them fight it out. With director and producer at war, the actresses felt ignored. They believed that the script portrayed them as interchangeable—and threatened to quit. "The more they were quitting, the more fun it was for Jack," says a Warner's source. "Jack would stir them up and then sit there and laugh."

Bob Daly told Peters to pull the Madonna track. Peters leapt on top of Daly's desk— and began jumping up and down.

As the shoot progressed, tensions escalated between Miller and Peters, who took out his fury on whoever available. Peters threw a chair during a meeting with Sarandon. "He was really rough on Sue," says Cher, "really disrespectful." Peters barred Sarandon's daughter from the set, then brought visitors—including Barbra Streisand—to watch the filming on a particularly difficult day, enraging the actresses. Peters tried to placate Cher by offering her jewelry. "What do you think I am, a whore?" she retorted.

One scene required Cher to be covered with snakes. "Which one is Jon Peters?" she inquired, entertaining the crew. "Here he is," she said, pointing to a reptile. "And the little one is Mark Canton."

The studio seemed unable or unwilling to address the problems. On one occasion, Peter Guber showed up—with no discernible effect. "I don't know if he actually did anything," says Cher. "Jon Peters at least would scream and yell, and you knew what he was thinking. . . . You never knew what was going on with Guber. I mean, he would just smile."

The film was a $64 million hit, but a taste of success in the movie business only made Guber and Peters hungry for more. Peters, particularly, saw the world as his for the taking, and had heard of a man who could help: Drexel, Burnham, Lambert's Michael Milken, the junk-bond king, Frank Wells, Disney's president, took Peters to Milken's lush Beverly Hills offices one morning at 4:30, the hour when Milken met supplicants. Milken consigned him to his protege Terren Peizer.

Peizer doubted he could get any investors to bankroll Peters and Guber in a play for a company. But they had friends who just might ante up. Streisand's name was bandied about—and, rather surprisingly, Steven Spielberg's— as the threesome toyed with ideas. Peters tried to get Warner's to finance the purchase of the Six Flags amusement-park chain. He planned to rename it "Guber and Peters's Six Flags." Nothing materialized, and as time passed, Peizer's attention shifted to Guber, who was talking to Columbia Pictures about returning there to head the studio. Guber's partnership with the volatile Peters was proving exhausting. He told Peizer he was getting restless. Peizer urged Guber to "do something bigger first."

Peizer had a brainstorm: he would match Guber and Peters with Burt Sugarman—an eccentric, ruthless former car salesman who now owned a cement firm and dabbled in the entertainment world. Sugarman had scored his biggest success with Midnight Special, a latenight show featuring rock acts. In 1987, Sugarman had bought a controlling interest in Chuck Barris's production company, which made game shows such as The Newlywed Game. He had met Peizer that same year at the Predators' Ball, an annual conference of Drexel clients. Sugarman was raising $60 million through Drexel, and wanted to parlay his cash into something big.

"So I had this thought," says Peizer: Sugarman should acquire the GuberPeters production company.

For the purposes of the deal, Peizer made the "assumption" that the GuberPeters production company was worth about $50 million. Based on Drexel's valuation, Peters and Guber would receive Barris stock and short-term notes worth nearly $30 million, based on the stock's value at the time.

Peizer felt that he was giving Guber and Peters a spectacular gift. They were then splitting around $7 million before taxes in their best year. But they hesitated, and Peizer became irritated. Didn't they realize that Barris would be acquiring a company that Peizer had almost made up? After brokering the deal, Peizer washed his hands of the partners. "I think they didn't realize what I had just done for them. . . . They're very greedy."

In December 1987, the merger with Barris went through. "We're a real studio now," Peters crowed to the Los Angeles Times. "I want to build another MCA." At a meeting of prospective investors, one staid business type asked about the partners' vision for the company. Peters obliged, saying, "This might be a little seed right now, but it's going to germinate into a fucking sequoia."

Ultimately, problems arose from the fact that Sugarman had retained power to vote all shares. He had control and spent money liberally—but not on empire-building moves. Instead he pursued costly, predatory dreams, flying around on his Gulfstream and billing the company. Peters and Guber, who had logged their share of air time on the Warner's jet, fought with him constantly over the use of the plane. "You thought somebody was going to get killed," says Chris Bearde, a Barris producer. "Burt had this cement factory and there was this joke that somebody was going to end up in cement."

The three partners announced a new talk show with Kenny Rogers, but it never jelled. Jeff Wald, now an executive at Barris, maintains that Sugarman had offered Rogers so much—$12 million in the first two years—that Barris could never have made money. In another disastrous interlude, Sugarman waged an expensive and futile battle for Media General, a Virginia-based company.

In July 1988, the partners announced that they intended to pay $100 million for 25 percent of the MGM studio, which was being dismantled bit by bit by its owner, Kirk Kerkorian. Peter Guber would serve as chairman and C.E.O.; Peters would be president and C.O.O. The majority of the company would still be Kerkorian's.

Since MGM's crown jewel—its film library-had already been sold to Ted Turner, it was unclear what the Barris partners were getting for their money. The only obvious answer was the Leo the Lion logo. But Guber and Peters dived right in, dashing around with Leo the Lion sweatshirts and gym bags.

Two weeks after the MGM acquisition deal was made public, it collapsed. Terry Christensen, Kerkorian's attorney, says it fell apart because the Barris team couldn't decide what to do. Other sources believe the Barris team was having difficulty with financing. The abortive deal cost Barris $5 million. In October 1988, the company reported a net loss of $6.9 million for the quarter that ended August 31. Revenue had dropped 13 percent.

Ultimately, Frank Lowy, an Australian shopping-mall and TV magnate, paid $13 per share to buy out Sugarman. It was an exorbitant price. But Guber and Peters didn't get along much better with Lowy than they had with Sugarman. Both men wanted out of the firm, which had been renamed the Guber-Peters Entertainment Company (G.P.E.C.). Not four months later, a new mountaintop came into view. Gary Winnick, a former Milken associate and a shareholder in G.P.E.C., picked up the rumor that Sony was poised to buy Colum bia Pictures.

"Peter was told he would have to give Lynda half his assets. He called her up and said, `Hi, honey. I'm coming home."

ACT IV

FLASHBACK

By the time they began plotting how to horn in on the Columbia deal, the dynamic duo of Guber and Peters had "made" Rain Man and Batman, films that created the impression that their makers' instincts were so brilliant that they could run a major studio. But neither Guber nor Peters had initially shown much interest in the first project.

Michael Ovitz, then CAA's superagent to the stars, is credited with actually getting the picture made with his clients—Dustin Hoffman, Tom Cruise, and director Barry Levinson.

In 1986, writer Barry Morrow pitched the Rain Man story, of a car salesman who takes a road trip with his autistic brother, to Roger Birnbaum, then president of the Guber-Peters company. "This is the best story I ever heard," Birnbaum said. Guber, unimpressed, told Birnbaum to find an interested studio.

United Artists president Robert Lawrence immediately bought the project, and Birnbaum spent eight months developing the script with Morrow. Birnbaum's contract guaranteed that he would receive a producer's credit and a percentage of the profits if the picture was made. At the same time, however, he was being wooed by United Artists to become its president of production.

According to Birnbaum, his bosses agreed to let him out of his contract to take the UA job, but promised to continue his financial participation in Rain Man and other films he had developed. So he went off to United Artists.

In the meantime, Ovitz had gotten Dustin Hoffman and director Martin Brest interested in Rain Man. Brest soon fell by the wayside because of differences with the notoriously perfectionistic Hoffman. Directors Steven Spielberg and Sydney Pollack both joined and left the project. Finally Ovitz brought in Barry Levinson, whose longtime associate Mark Johnson took over producing chores.

Guber and Peters, Rain Man s executive producers, visited the set just once, winging in on the Warner's jet when the production was in Las Vegas. They chatted with Levinson, Hoffman, and Cruise and had pictures taken. Jon reportedly asked Hoffman, "Are you playing the retard or the other guy?"

When it came time to sell the movie, Guber jumped in to persuade UA to spend more money on marketing. "Peter was involved in several marketing meetings and was quite helpful," says Mark Johnson. "I actually learned a lot from Peter in those meetings."

But for Roger Birnbaum the horror was about to begin. He asked Guber and Peters about his promised credit; he believed he would be listed along with his former bosses as an executive producer. Guber and Peters, however, weren't forthcoming.

"Jon would say, 'It's O.K. with me; you gotta ask Peter.' And I'd go to Peter, and he said, 'It's O.K. with me; you've gotta go ask Jon.' They played that game until I realized they were just bullshitting me," Birnbaum says. Levinson, however, granted Birnbaum a special credit at the end of the film.

"Rain Man belongs to a lot of people," Johnson told nearly a billion people when he collected the Oscar for best picture of 1988. He thanked the long list of people, including Roger Birnbaum, who had contributed to the winning project before it fell into his hands. Yet most film aficionados probably don't recall that Mark Johnson actually produced Rain Man. They may, however, have a vague recollection that Guber and Peters were associated with the film.

In a widely circulated photograph taken at the Governor's Ball following the ceremony, the pair posed, ebullient, holding a Rain Man Oscar—which they had borrowed from screenwriter Morrow.

Like Rain Man, Batman began as someone else's baby. Since childhood, Michael Uslan had been obsessed with Gotham City's Caped Crusader. In partnership with Ben Melniker, a former MGM executive who had worked on Ben Hur and Doctor Zhivago, he was determined to produce the definitive Batman movie. Uslan and Melniker persuaded D.C. Comics, which had resented the silly portrayal of Butman in the 60s television series, to sell them licensing rights for a series of movies.

Uslan and Melniker pitched the idea to Casablanca in 1979. Guber was enthralled. "I love it," he said. "I get it." The partners entered into a complicated joint venture with Casablanca which guaranteed Melniker and Uslan 40 percent of whatever profit Guber and Peters received. It also stated that they "shall be accorded credit as the producers of the picture."

When Jon Peters joined PolyGram Pictures in 1980, he met with Melniker and Uslan at the Carlyle Hotel in New York. Uslan provided him with a single-spaced, nine-page memo, dated November 6, 1980, which outlined his vision for a new Batman film. In it he recommended that Robin's character be eliminated or whittled down, and that the story focus on Batman's attempts to vanquish a villain called the Joker. Uslan even suggested casting for the Joker: Jack Nicholson.

When Guber and Peters affiliated themselves with Warner's in 1982, Melniker and Uslan assumed that the terms of the original deal would still apply.

In the next few years the project cooled—and then heated up again. Action began in earnest when Warner's production executive Bonni Lee seized on Batman as a vehicle for 27-yearold wunderkind Tim Burton, who was then directing Beetlejuice for the studio. Burton, a haunted-looking fellow, dressed in black and rarely spoke in complete sentences.

He wanted to make a dark, psychological study of the superhero. Sam Hamm, a young screenwriter, was brought in to fashion the script.

Burton met twice with Melniker and Uslan, who provided research. Eventually Hamm's script was green-lighted by Semel and Daly. Filming started in October 1988 at London's Pinewood Studios.

Melniker and Uslan read in the trade papers that Batman was going into production—and that Guber and Peters were taking credit as the producers. When they contacted Warner's head of business affairs, Jim Miller, to inform him that the studio was breaching the Casablanca agreement, they say, Miller told them if they did not sign an amended contract they would be thrown off the picture entirely. On September 8, 1988, they signed a new contract that gave them nominal credit as executive producers, stripped them of creative involvement and consulting rights, and granted them 13 percent of net profits. As all but the rankest amateurs in Hollywood know, net points are generally worthless. But Melniker and Uslan say that Miller told them, "If you don't like it, you can bring a lawsuit." (Warner's did not respond to calls.)

Peters came out carrying an old-style, pearl-handled six-shooter, yelling and screaming."

While Melniker and Uslan fretted, Burton got acquainted with his bosses. "When I first started the project," Burton recalls, "Peter Guber was the one I dealt with most. He talked too fast for me to understand sometimes."

For the key job of production designer, Burton chose Anton Furst to create a moody Gotham City and spiffy hightech Batgear. To play Batman, Jon Peters favored Michael Keaton, arguing that the actor had an edgy, tormented quality which suited the character. Semel and Daly finally agreed.

Despite a reputation for instability, Blade Runner star Sean Young was cast as photographer Vicki Vale. For the Joker, Mark Canton and Peters, like Uslan before them, had their heart set on Jack Nicholson. Nicholson met Burton and liked him, but the star still needed wooing. Peters jumped in. Wouldn't Nicholson like to jet over to London and see the sets? Nicholson said he wouldn't mind, | and Peters reserved I the Warner's Gulfj stream III.

Peters planned a few restorative surprises for the trip—noW tably a personal trainer * and masseuse. After the jet took off, Nicholson worked out and had a massage before sampling some caviar. After they returned to L.A., Nicholson told Peters he'd be the Joker and then cut himself a deal for $6 million plus a percentage of the film's gross earnings. (Eventually he would make a reported $50 million.)

Burton had heard all the Jon Peters stories and he soon got a taste of what George Miller had experienced during the making of The Witches of Eastwick. He had expected to shoot the Sam Hamm script, but found to his dismay that Peters, backed by Warner's, wanted extensive revisions. A brooding superhero who needed Prozac and couldn't get a date was hardly Peters's idea of entertainment. He bore down on Burton, whom he alternately tyrannized and coddled.

A major crisis occurred when Sean Young fell and broke her arm just before filming. Burton wanted Michelle Pfeiffer to replace her. But Keaton had just ended a romance with Pfeiffer, so Peters and Mark Canton settled on Kim Basinger, who was whisked to London with her husband. During an evening out, Peters was angered by what he considered to be the husband's verbally abusive treatment of the star. He reached across the table and grabbed him by the neck, and the men nearly got into a brawl. Thereafter, Peters considered Basinger fair game. (His own marriage to Christine Forsyth had ended.) When Basinger's husband left town, she began an affair with Peters, which lasted for the duration of the shoot.

"My sweetheart hoodlum," she called Peters. Some nights she could be seen in her pajamas leaving her hotel room at the St. James Club, toothbrush in hand, heading up to Peters's penthouse suite for the night.

At Peters's behest, Anton Furst came up with the simple but evocative Batsymbol that would become ubiquitous even before the film opened. "That's exactly what we want," Peters exulted when Furst showed him his sketches. Peters envisioned the poster as consisting solely of the logo and the June 23, 1989, opening date. "I wanted to do, like, foreplay, to create the magic and myth of it all," Peters said later. When Warner's balked, he waged an all-out war to do it his way.

There were other wars: by the time Batman wrapped, Jon had made himself unpopular with the British crew. He had taken them off the payroll during a three-week Christmas break. (It is customary for crews to be paid over holidays.) Money was also an issue in a flap over the top-of-the-line black leather crew jackets which displayed the Batman logo. Nicholson and Peters had agreed to split the cost of the jackets over and above the $10,000 allotted in the budget. But when a bill arrived for $100,000, Peters reneged.

When Nicholson was told that it would cost him $90,000 to cover the cost, he stormed over to Basinger. "Tell that guy whose cock you've been sucking for the last six months that he's an asshole for not paying for those jackets!" he snapped. That, at least, was the story that was gleefully reported back in Hollywood for months. Warner's ultimately absorbed the cost of the jackets.

It was worth it. On the Monday morning after the film's opening, the trades trumpeted the good news: Batman had taken in $42.7 million at 2,100 screens, breaking every record in motion-picture history. Within 10 days, it grossed more than $100 million, another record.

On March 26, 1992, Michael Uslan and Ben Melniker filed a breach-ofcontract suit in Los Angeles County Superior Court, claiming that they were "the victims of a sinister campaign of fraud and coercion."

The judge threw out their case, which is now on appeal. Uslan and Melniker have had to console themselves with their executive-producers' fee of $300,000 apiece. Seven years after the release of Batman, with total box-office revenues topping the $400 million mark, Melniker and Uslan have not seen a penny of their 13 percent of net profits. Their net-profit participation has proved worthless. According to Warner Bros., Batman is still in the red.

ACT V

THE SCORE

In September 1989, Walter Yetnikoff, freshly out of drug rehab at the Hazelden Clinic, found himself at the epicenter of a multibillion-dollar deal. Yetnikoff, the head of Sony Corporation's successful music division, was playing a pivotal role in the Japanese electronics giant's acquisition of Columbia Pictures. The cost, $3.4 billion plus $1.6 billion in debt, was considered high. But that wasn't the hang-up. If the deal was to "make," in the industry parlance, Sony needed managers to put in charge of the new studio. Under pressure, Yetnikoff had an idea: he would call his old friends film producers Peter Guber and Jon Peters. He phoned Guber in L.A. on a Thursday night and the two men met for dinner in Manhattan two days later.

Not long after, on Yetnikoff's recommendation and with financial advice from the Blackstone Group, Sony rocked Hollywood and Wall Street by hiring Jon Peters and Peter Guber—a pair of cowboy producers with little corporate management experience between them—as co-chairmen of its new studio. But it was the lavish terms of the deal that truly stunned industry insiders: not only did the Japanese agree to pay $200 million for Guber and Peters's money-losing production company (about 40 percent above its market value), but Sony also awarded them an unprecedented compensation package, including $2.75 million apiece in annual salary, a $50 million bonus pool, and a stake in any increase in the studio's value over the next 1 five years.

But that wasn't all.

Sony had to take another whopping financial hit and endure a public humiliation as well. The company's executives had believed Guber and Peters's assurances that Warner Communications Inc. chairman Steve Ross would release them from their recently signed five-year deal to let them run Sony. But no sooner was the ink dry on the new deal than an enraged Ross and Warner Bros, slapped the Japanese with a bill ion-dollar breach-of-contract lawsuit. Sony eventually had to pay Warner's an estimated $800 million ransom to settle out of court—and win the services of the Batman boys.

EPILOGUE

If Guber and Peters regretted that Sony had to spend so much to hire them, they didn't show it by exercising fiscal restraint in their new jobs. Continuing the pattern formed at PolyGram, they spent big from the start, setting off a wave of inflation that is still being felt in the movie business today. Guber and Peters took Sony on the wildest and most profligate ride that Hollywood had ever seen. For five years, Sony executives in Tokyo and New York stood by while the studio lost billions and became a symbol for the worst kind of excess in an industry that is hardly known for moderation. There were box-office bombs, lavish renovations, and extravagant parties against a backdrop of corporate intrigue, expensive firings, and even a call-girl scandal.

"You know why I loved being partners with you?" Guber asked Peters. "You had the prettiest girlfriends."

The ill-advised pairing of the Japanese corporation with Hollywood's cleverest rogues would culminate, as one insider delicately put it, in "the most public screwing in the history of the movie business."

After he achieved his dream of becoming co-chairman of Columbia Pictures, Guber decided he would rather do the job alone. In April 1991, Guber orchestrated the firing of his longtime partner. After he was pushed out, Peters says, Guber would occasionally call and pretend that nothing had gone wrong. Once, Guber asked Peters to a screening. As they drove to the theater together, Peters found that he could not continue the charade. "I broke down in the car and started crying, and said, 'How could you do this?' " he remembers.

According to Peters, Guber had cried, too, and began to reminisce about Neil Bogart. Peters surmised that there was a parallel between the situations in Guber's mind. "He left Neil for me and he felt guilty," Peters says. As he often did, Peters began to hope that reconciliation was possible. "He said something like 'You know why I loved being partners with you?' And I thought he was going to talk about all the creative and emotional experiences we shared. And he looked at me and said, 'I was always jealous of you because you had the prettiest girlfriends.'"

Peters was floored by Guber's statement. "It was like part of me died," he says. "He could not acknowledge my existence."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now