Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowEditor's Letter

The Colony Club

In this issue, two of Vanity Fair's besttraveled correspondents, Alex Shoumatoff and Christopher Hitchens, descend upon Africa and Asia to explore the sorry legacy of imperialism—British, Belgian, French, and American. Especially American. Shoumatoff, who has been in Zaire four times in the last four years, was in Kinshasa when Zairean dictator Mobutu Sese Seko fled the country after 32 years of corrupt, despotic rule. Mobutu's successor, rebel leader Laurent-Desire Kabila, swept into town in an executive jet and immediately went to work, banning the opposition political parties and changing the country's name back to what it had been when it was annexed as a colony of Belgium in 1908: Congo. (The explorers Sir Henry Morton Stanley and David Livingstone had tried to interest the British in the Congo, but failed. It became for years the private estate of Belgium's King Leopold II, much as a large part of India had been the preserve of the British East India Company prior to becoming part of the British Empire in 1858.)

Though Belgium was forced to grant the Congo its freedom in 1960, the C.I.A. plotted the murder of the leader of the independence movement, Patrice Lumumba (too close to Moscow, it was thought), and then helped engineer the 1965 coup that brought Mobutu to power. The French propped up Mobutu for the next three decades, as he reduced Zaire—which, with its colossal reserves of copper, cobalt, diamonds, and strategic minerals, is potentially one of the world's richest countries—to beggary (per capita income is $115). As Shoumatoff writes in "Mobutu's Final Days," on page 92, the U.S. is once again engaged in "a covert war for the resources" and the sphere of influence. Don't expect the people of Congo to come out ahead of the game any time soon.

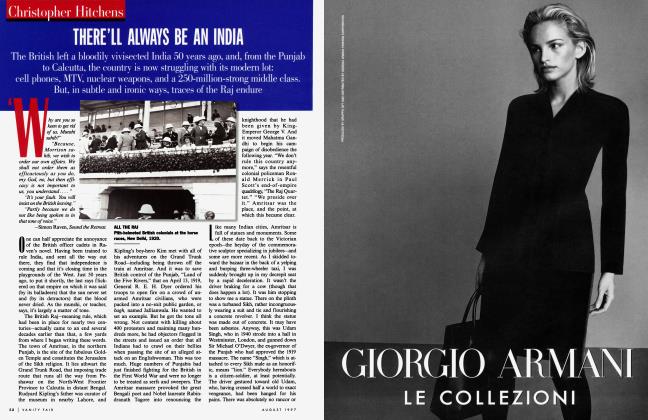

In almost every way, India, 50 years after its independence, is much better off than the African nation. "There'll Always Be an India," Christopher Hitchens's report on page 52, is a portrait of a rapidly modernizing country with a quarter of a billion citizens classified as "middle-class." India, despite its half-century of independence, still owes much—printing presses, railroads, even its lingua franca—to its former colonists. And yet, as Hitchens points out, on either side of the frontier created by the bloody 1947 division of India into India and Pakistan, as the British scrambled for a way to dump their burden, "there is still one of the most toxic and unstable concentrations of latent violence in the world."

As portraits of nations in transition, Shoumatoff's and Hitchens's dispatches are operatic in scope and elegant in style. And they are just the sorts of stories that have resulted in Vanity Fair's receiving a slew of accolades this year, including the National Magazine Award for General Excellence among publications with a circulation of a million or more. It is the most coveted award in the magazine business. And it's testament to the talents of Vanity Fair's unrivaled stable of writers, photographers, and artists.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now