Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

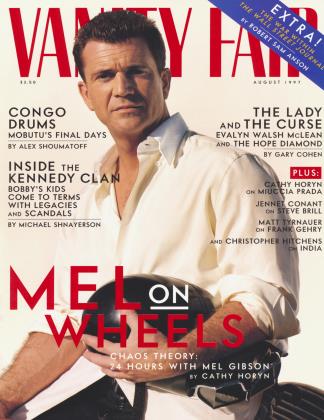

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowWith must-have bags, shoes, and clothes, Miuccia Prada has turned her grandfather's 84-year-old luggage business into a $750-million-a-year arbiter of international style. But nothing expresses her independent streak like the early-19th-century villa in Milan where she lives with her husband and partner, Patrizio Bertelli, and their two sons. CATHY HORYN finds Prada's center of gravity under the skylights and vaulted ceiling of the fashion star's 2,500-square-foot living room

August 1997 Cathy Horyn Pascal ChevallierWith must-have bags, shoes, and clothes, Miuccia Prada has turned her grandfather's 84-year-old luggage business into a $750-million-a-year arbiter of international style. But nothing expresses her independent streak like the early-19th-century villa in Milan where she lives with her husband and partner, Patrizio Bertelli, and their two sons. CATHY HORYN finds Prada's center of gravity under the skylights and vaulted ceiling of the fashion star's 2,500-square-foot living room

August 1997 Cathy Horyn Pascal Chevallier'I like the idea of living in the same place where I was born," says Miuccia Prada as her cigarette-smoked contralto eddies through the silence. The Italian fashion magnate, despite her aesthetic of cool, anonymous chic, turns out to be as nostalgic as Proust. "Miuccia, she's an old gypsy!" roars photographer Manuela Pavesi, her great friend. "She's kept the same house and the same friends as before she married. She's really somebody who's very sentimental." And so this most paradoxical woman—70s-era Communist, art collector, clotheshorse from way back—has chosen to remain in her childhood home, a pink-washed early-19th-century building on Milan's Corso Porta Romana, where her mother, brother, sister, and aunt also have apartments. Now that Prada has turned a once slumbering family luggage business into a $750-million-a-year arbiter of international style, she and her Tuscan-born husband and business partner, Patrizio Bertelli, could certainly afford to play Milanese Monopoly—the fashion kingdom's ever popular game of outdoing your rivals by increasing your palazzo count. Is she tempted to make a move?

"Never!" she says with her wicked, throaty laugh. "I like a different kind of luxury. We have a palazzo in Tuscany, a real palazzo, but it's empty." She giggles. "We live in our country house." And why, I ask, not in the palazzo? "Because I hate it! I always hate the bourgeois rich. . . . It's typical of the old Milanese bourgeois. The more you are rich, the more you have to be simple. I am the vulgar one in my family, because I have more. But in some ways I inherited this idea that showing money is really vulgar." She flashes a smile. "I also have my own political ideas." She is referring to earlier years spent in the Italian Communist Party. Still, it is hard to imagine the theory that would explain Miuccia the Marxist espousing power for the proletariat as the famous and rich rush for the elegant Prada fashions so subtly showcased in all those glossy new stores. One opened in New York last fall, and 39 more boutiques are set to swing into action by year's end.

The secret of her phenomenal success may be wrapped up in the way this 46-year-old fireball remains just outside fashion's all-consuming orbit. She's funny and smart, self-deprecating and delightfully mellow. "It's easy for her to take risks," says Franca Sozzani, the editor of Italian Vogue, "because she doesn't care." Of late, Prada has been looking for ways to shake things up a bit. "She's desperate to have fun," says Pavesi. "No matter what's happening, she will find a little way to turn things into fun." At one point during my visit in Milan—Patrizio was away on a business trip and their sons, Giulio and Lorenzo, were at the family's mountain retreat in Saint-Moritz—Prada confided, "Right now in my life I want to go to dance."

"You mean modern dance?" I ask her, trying hard to imagine the designer in a Twyla Tharp number.

"No! Discotheque!" she exclaims. "I never danced when I was young, and in politics I did not dance, but I really like it. You work and work, and there are so many problems. So, unless nothing really horrible is happening, you have to be really happy. And I hate the idea of being depressed without the reason." Her eyes glow. "So, I always say, until you have the really big problem, you have to laugh."

Needless to say, things can get pretty hectic when the family is in residence at Corso Porta Romana. There's a lot of good-natured shouting between Prada and Bertelli. Friends drop by. He cooks. "When Patrizio's around," says Pavesi, "we'll have a great dinner. But if he's not, then Miuccia, she's lazy. She will give us some cheese and bread and then we will complain." The household revolves around the startlingly white, 2,500-square-foot living room, which functions simultaneously as a playroom, library, art gallery, and dining room. "Originally, this was a garden," Prada explains as I watch her jagged profile shooting its gaze up to the vaulted ceiling and skylights. "But after the Second World War, my father built this. It was just for merchandise." She inherited the apartment in her 20s, after she had gone to work for Fratelli Prada, the leather-goods company founded by her grandfather Mario in 1913.

A long corridor links the front of the apartment to the back, branching off into the children's room, which Prada has outfitted with ship-style bunk beds (each fancifully curtained and lit), and the master bedroom, with its frescoed ceiling and patchwork coverlet of antique silks and velvets. I note a collection of Disney videos stacked on a windowsill and ask if her sons, like most children, prefer to do their viewing from their parents' bed. "As you can see, yes," she says. "In the big bed." Lorenzo and Giulio also like to display their latest drawings across its polished headboard.

Four years ago, Prada and Bertelli became interested in contemporary and avant-garde art and began to seriously collect works by Brice Marden, Robert Irwin, Anish Kapoor, Walter De Maria, Alberto Burri, Nino Franchina, and the Italian artist Lucio Fontana, whose La Fine di Dio they recently acquired. And they've opened a private foundation to support modern art. But as they have become more acquisitive, Prada has found she's had to simplify the rest of her surroundings. "I always thought that changing your home was like changing your style—it was really awful," she admits. "But sometimes you get bored and you have to change something. It's a response to your interior feeling."

Prada says, "Originally, I liked the idea of a really traditional home, and I'm crazy about antique fabrics. So we had antiques and draperies. But now I want to change. I want to have the same feeling of mixture, but not with antique fabrics. Also, my husband is fed up—and me too— with drapes everywhere." For instance, a pair of minimalist sofas which Prada and her husband designed and which form the central seating area of the living room have recently been re-covered in lilac and gray wool velvets, fabrics that Prada says are also used in the first-class compartments of Italian trains. More exotic is a large zebra mg with tufts of mane sprouting from it.

"This is a fantastic carpet," the designer says excitedly. "I bought it from a house in Florence, from a famous jeweler who was also a painter. And I bought this"—she darts around the corner to the kitchen—"and this." I look up at the enormous mounted horns of six buffalo, which she pronounces "boofalo." Apparently the jeweler was also a good shot. "I was going to put them in the house in the mountains, but I liked them so much I put them here," Prada says, dreamily regarding her surreal display. "It's like a butcher's."

What one notices most about Prada is her complete guilelessness. What you see is what you get. "She's coming from the 70s, and when you're of the 70s, you have a kind of freedom in your mind," says Pavesi, who met Prada in 1972, when in some complicated Karmic conjunction the women spied each other in identical Yves Saint Laurent outfits. "This freedom stays forever with you. She believes that what's important is what you are and not what you own."

Her rambunctious surroundings testify to her liberated mind: the children's toys scattered freely among the antiques and sculptures, a beautiful Lehmann model train set running in between the furniture. "I think this life should be all connected," Prada says. Interview editor Ingrid Sischy, who, in a 1994 New Yorker piece, wrote about the connection between Prada's interior life and the clothes she designs, has been a dinner guest and observer of the scene: "It's kind of a cohabitation, but everyone is doing their own thing at the same time. The kids are usually sitting on the couch by the television or on the floor. Miuccia is often at the dining-room table. Patrizio is usually in the kitchen—he's one of the greatest cooks in the world. There's the shouting going back and forth. There's Miuccia dealing with the children, to whom she's very attentive, and her guests. It's very spirited, but with multiple spirits. It's chaotic, yet there's a calm."

'Ahwoooooo," says Manuela Pavesi, "that's a very funny question." The photographer is on her way to join Prada and Bertelli in Saint-Moritz (along with 30 friends and 250 bottles of wine) when ask her what they plan to wear. "We've been discussing that," Pavesi says. "We decided to wear the dirndl again, but in a different way. More loose and not with the apron. And not to put any blouse underneath, but old lingerie." Pavesi adds, "Our weakness has always been not to look what is the best, but to follow our dreams."

And dreams are good company on a warm summer night in Milan. Prada and I go out. We order wine, steaks pounded thin, more wine, fig tarts. In a few days she will be in the mountains, hiking six and seven hours a day. She will put on a dirndl, "with heavy shoes, socks—very German," she laughs. "My mother grew up in dirndls because my grandfather was obsessed by German costumes and culture," she says. "She is 78 and still wears them." Actually, this says a lot about the way Miuccia works—taking these incredibly arcane styles and whipping them into modern status symbols.

"You are part of your past, your memories," she says in a mellowing voice, "but you have to live what you want to be now. To me, this is harmony. Anyway, I'm in a good moment of my life."

"You have to live what you want to be now. To me, this is harmony"

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now