Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

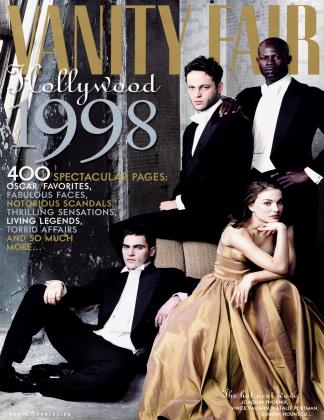

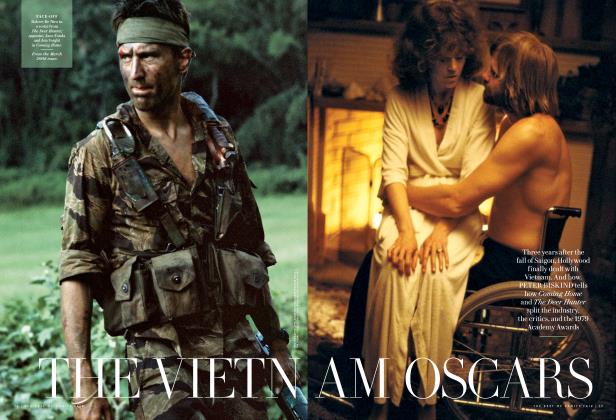

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowRAGING DAYS, BOOGIE NIGHTS

The Young Lions

In the early 1970s, a handful of young directors—Francis Ford Coppola, George Lucas, Steven Spielberg, and Martin Scorsese among them—were given the keys to the Hollywood kingdom. With movies such as The Godfather;American Graffiti,andMean Streets, they rocked the studios and changed the culture forever

PETER BISKIND

We were just guys who wanted to make movies, and we knew we could be cut down at any second by the studios," says Martin Scorsese of the talented circle of “movie brats” who helped create the New Hollywood. “It was like we were in foxholes with the shells falling around us.”

But it wasn’t bombs, or even studio warfare, that jolted the 28-year-old Scorsese in his room at Burbank’s Toluca Motel at one minute past six A.M. on February 9, 1971. It was an earthquake registering 6.5. As a scattering of headlights broke the pre-dawn gloom and the recent L.A. immigrant dreamed of rare books, the ground heaved. Scorsese, who had just gotten a job at Warner Bros., thought it was the Big One. “Lightning was slashing across the sky—it was the falling wires from the telephone poles. I pulled on my cowboy boots and went to the Copper Penny. There was a big aftershock. I got up to run, and a guy looked up and asked, ‘Where you going to go?’"

The quake was gilding the lily—as Hollywood is wont to do. The convulsion upending the industry had started a decade earlier with a series of premonitory tremors—civil rights, the Beatles, the pill, Vietnam, sex, drugs—that shook lives. And, eventually, studios.

“I had brought George Lucas along with me wherever I went,” says Coppola, “but he didn’t bring me aloig with him.”

Because movies take so long to get made, Hollywood registers change slowly. It took some time for the seismic shifts to reach the studio gates. The dream factories were still in the rigor-mortis-like grip of the Old Guard. In 1965, Adolph Zukor, 92, and the slightly more juvenile Barney Bala ban, 78, survived on Paramount’s board; Jack Warner, 73, ran Warner Bros. Darryl F. Zanuck, 63, commanded Twentieth Century Fox. “If you were these guys, you weren’t going to give this up, ” says Ned Tanen, who would later head Universal’s motion-picture division. “To do what, sit at Hillerest Country Club and play pinochle?”

Then, suddenly, it all changed. As America burned, Hell’s Angels sped down Sunset, and the music of the Doors throbbed on the Strip. “It was like the ground was in flames and tulips were coming up at the same time, ” recalls Peter Guber, a trainee at Columbia who later headed Sony Pictures Entertainment. It was cultural revolution, American-style. As Steven Spielberg says, “It was just an avalanche of brave new ideas.”

In 1967, the venerable Jack Warner sold his stake in the studio which bore his name to a TV packager, Seven Arts. Eliot Hyman became C.E.O. and his son Kenneth head of production. Kenny announced that he would woo directors by allowing them to retain more artistic control over their work. He gave a young in-house writer a shot at directing a Fred Astaire musical, Finian’s Rainbow.

The year before, Francis Ford Coppola, a 28-year-old U.C.L.A. film-school graduate, had directed his first serious feature, You’re a Big Boy Now, from his own script. “It was unheard of for a young fellow to make a feature,” Coppola recalled. After shooting wrapped, the proud filmmaker walked the streets of New York with his chest thrust out. Then someone told him, “There’s another young director who’s made a feature, and he’s only 26.” Coppola was shocked. “It was Willie Friedkin.” (The young director, who would win the Oscar in 1971 for The French Connection, was actually several years older than 26 when he made Good Times, with Sonny and Cher.)

You’re a Big Boy Now opened in March 1967. The Los Angeles Times termed it “one of those rare American things, what the Europeans call an auteur film.” Coppola bought a Jaguar and installed himself and his wife, Eleanor, in an A-frame in Mandeville Canyon. Friedkin was a frequent visitor, and Coppola tried to fix him up with his sister, Talia.

Eleanor was an artist and tapestrymaker who favored beads and long skirts of orange, purple, and other outrageous colors. Her bearded husband, a hefty five feet eleven, wore horn-rims with thick lenses. He was terminally rumpled and generally clad in fatigues, boots, and a cap.

For his next film, Coppola reluctantly accepted Finian’s Rainbow, with its dancing leprechauns, sentimental score (the big numbers included “How Are Things in Glocca Mora?”), and rock-bottom budget. One day the director spotted a slight young man of 23 shyly watching him work. As the days passed, Coppola noticed that the young man always wore the same outfit: black chinos, a white T-shirt, and white sneakers.

George Lucas was the U.S.C. whiz kid whose 15-minute short, THX 1138: 4EB/Electronic Labyrinth, had recently taken first prize at the third National Student Film Festival. His six-month Warner scholarship allowed him to do whatever he wanted on the lot.

Lucas was almost pathologically shy. When he met the woman he would marry, film editor Marcia Griffin, it was months before she could extract his place of birth. “He would never volunteer anything about himself,” she remembers.

With his fellow director, however, Lucas could talk movies, and Coppola recognized a kindred spirit. But after two weeks of watching his new friend struggle with Finian’s Rainbow, Lucas decided he’d seen enough. Coppola was annoyed. “What do you mean, you’re leaving?” he asked Lucas. “Aren’t I entertaining enough? Have you learned everything you’re going to learn?” He offered him a slot on the production. Lucas fell under Coppola’s spell.

His new mentor had a major impact on Lucas. Coppola was always telling him he was a genius, building his ego. According to Marcia Lucas, who is now divorced from the director, “George was not a writer, and it was Francis who made him write. Francis said, ‘If you’re gonna be a filmmaker, you have to write.’ He practically handcuffed George to the desk.”

Their disparate styles were a source of friction. “My life is a kind of reaction against Francis’s life,” Lucas explained. “I’m his antithesis.” Coppola was large and bulky, Lucas small and frail. Coppola was emotional, Lucas reserved. Coppola was collaborative to a fault. Lucas, a control freak, would have done everything—write, shoot, direct, produce, and edit—himself. No matter how little money Coppola had, he always acted like a man with more. No matter how much money Lucas had, he always acted like a man with none. Coppola referred to Lucas disparagingly as the “70-year-old kid.” Of Coppola, Lucas said, “All directors have egos and are insecure. But of all the people I know, Francis Ford Coppola has the biggest ego and the biggest insecurities.”

Two years later, Coppola persuaded Lucas to help him start a new company, American Zoetrope, in San Francisco. “Francis saw Zoetrope as a sort of alternative. Easy Rider studio,” said Lucas. “It was a way of saying, ‘We don’t want to be part of the Establishment.’” Marcia Lucas has a different take on Coppola’s move from L.A. “I think Francis didn’t want to be a small fish in a big pond,” she says.

Meanwhile, Steve Ross had bought Warner-Seven Arts. Ted Ashley became the new head of the studio. Producer John Calley was named head of production. About a week after taking charge, Calley got a telegram that said, “Shape up or ship out.” It was signed “Francis Ford Coppola, American Zoetrope.”

Amused, Calley called to ask what the director was up to. Coppola shared his plans for Zoetrope and talked up Lucas. “George was like a younger brother to me,” he says. “I loved him. Where I went, he went.” In future years, after the Star Wars series made Lucas more successful, commercially, than his mentor would ever be, Coppola became embittered. “I’m the only one of George’s friends who never had a piece of Star Wars,” he says. “Once George went on, he went on. I had brought him along with me wherever I Went, but he didn’t bring me along with him.”

Excerpted fromEasy Riders, Raging Bulls, by Peter Biskind, to be published in April by Simon & Schuster; © 1998 by the author.

CONTINUED ON PAGE 225

CONTINUED FROM PAGE 220

But that was later. At the time, Coppola told Warner that Lucas was “a gigantic talent,” and pitched THX 1138, a feature based on Lucas’s short which he would produce for his friend.

Lucas shot the film on a shoestring, editing in his attic in Mill Valley. The picture was screened on the Warner Bros, lot in May 1970 for Warner executives. One of them, who sat next to Coppola, was appalled. He said, “Francis, what’s going on? This isn’t a commercial movie.” Coppola, who had seen a few reels of the film the night before and had commented, “This is either going to be a masterpiece or masturbation,” turned to the executive and replied, “I don’t know what the fuck this is.”

It was clear to the Warner executives that Coppola had been telling them what he knew they wanted to hear—“I’m going to supervise him,” etc.—while telling Lucas, “Do your own thing, it’s gonna be great.”

The studio decided to recut the film. As Lucas put it, “They were cutting off the fingers of my baby.” The thing that Warner executive Fred Weintraub liked about Lucas’s film was what he called “the freaks,” the hairy dwarfs who appear at the end. (They were later transformed into the Wookiees of Star Wars.) He told Lucas, “You gotta put your best stuff up front . . . put the freaks up front.”

Weintraub didn’t convince him. “George knows how to fight,” says Walter Murch, a legendary sound designer and film editor who worked on THX 1138 and, later, Coppola’s The Conversation.

THX 1138, shot in 1969 for $800,000, opened—and closed—in 1971. Even Marcia didn’t like it. “But George,” she remembers, “just said to me I was stupid and knew nothing. He was the intellectual.” The film was death for the alliance that Coppola and Zoetrope had previously made with Warner. “I’m a fucking artist, you’re philistines,” Coppola told a Warner executive, according to one source.

The THX 1138 Fiasco strained the friendship of the two young men. Lucas felt Coppola had let him down and wasn’t there to help him fend off Warner. “I needed to go and develop another project. I couldn’t rely on Zoetrope,” says Lucas. He was often on the phone now, hustling editing gigs for his wife, laying the groundwork for his next movie, American Graffiti.

One day Zoetrope’s treasurer, Mona Skager, opened the phone bill and flipped out. According to Coppola, she confronted Lucas, saying, “You’ve run up an $1,800 bill with all these calls, and none of them are about Zoetrope business.” Lucas had to go to his father, a conservative businessman who disapproved of his son’s career choice, for money to pay the bill.

When Coppola found out about all this afterward, he was furious. “It’s not my style,” he says of Skager’s action. “I always believed that incident was one of the things that pissed George off and caused a chill. I had always imagined George becoming the head of Zoetrope.”

Coppola was heartbroken. For all intents and purposes, Zoetrope was dead. “Everybody utilized it to get going,” he says, “but nobody wanted to stick with it.” Mike Nichols and Stanley Kubrick stopped taking his calls. But what really rankled Coppola was that Warner was demanding that he repay a $300,000 loan. Just when prospects looked gloomiest, Coppola got a message from Paramount about a project called The Godfather.

One fine day in the spring of 1968, Paramount had found itself with the opportunity to become the proud owner of the option on a 150-page manuscript by Mario Puzo, provisionally titled Mafia. The studio took a chance.

Paramount production chief Robert Evans “idolized gangsters,” according to one of his colleagues, Variety’s editor Peter Bart, then a production executive at Paramount, who adds, “But [they had to be] Jewish gangsters—Bugsy Siegel—not Italian ones.” Distribution suggested passing on the project. “There was no great enthusiasm for making The Godfather” recalls Albert S. Ruddy, who would be the film’s producer.

"Don't try to make The one of your films," Lucas advised Coppola. "Just roll over and let them do it to you."

Then the novel became a best-seller. When Universal offered Paramount $1 million for the option, Evans and company, in time-honored fashion, decided to go forward with the movie. Puzo was asked to update the script with hippies and other contemporary references.

Many directors, including Peter Bogdanovich, who was hot after The Last Picture Show, declined. Evans and Bart, considering the possibilities, concluded that they needed an Italian, to “smell the spaghetti.” Bart mentioned Coppola. “That’s your esoteric bullshit coming out,” snapped Evans. Then he told Bart to call him.

Bart had more trouble persuading Coppola. The Godfather was old-style genre—he considered himself above it. Bart hammered. “Francis, this could be a commercial movie,” he said. “It’d be irresponsible of you not to do it.”

The debt to Warner, not the only money Coppola owed, hung heavily on the director, who was in the editing room recutting THX with Lucas when Paramount made the offer. While Coppola was waiting for Evans to come on the line, he turned to his friend and asked, “Should I do this?”

“I don’t see any choice here,” Lucas replied. “Warner wants their money back. Survival is the key thing.”

After securing Coppola’s commitment, Evans and Bart still had to sell the director to Gulf & Western head Charles Bluhdom and company president Stanley Jaffe. Bart called Bluhdom in New York to tell him that Coppola was coming in to meet him. When Bart told his boss about the candidate’s previous pictures, the reaction was pure Bluhdom: “How dare you zend me Finian s fucking Rainbowl Id vas disgusting piece of shit.”

But later Bart got a call. “Da kid’z a brilliant kid,” Bluhdom exclaimed. “But can he direct?”

“Trust me, Charlie,” said Bart. “He can direct.”

Charlie Bluhdom was a balding and choleric man, with Lew Wasserman-style glasses clamped upon his broad nose. His mouth was filled with large, square teeth, like Scrabble tiles. A hugely successful financier, he played the commodities market and at meetings would announce, “Vile ve’ve been zidding here, I made more money on sugar dan Paramount made all year.” He had an infectious laugh, and could be charming, but mostly he screamed. His minions called him “Mein Fiihrer.”

He had vast holdings—sugar and cattle—in the Dominican Republic, where he reigned on occasion. He had armed guards and his own landing strip, where the company Gulfstream waited in readiness. When Gulf & Western absorbed the South Puerto Rico Sugar Company, Bluhdom developed a resort, Casa de Campo, where he built an elaborate guest compound called Casa Paramount. Its phalanx of maids, gardeners, and guards dressed in white posted themselves around the circular driveway to greet arriving guests.

The Gulf & Western chief was a man about whom it was impossible to be neutral. Evans was devoted. But the late producer Don Simpson, once a Paramount executive, called Bluhdorn “a mean, despicable, unethical, evil man, who lived too long. He clearly had a chemical imbalance and had no problem breaking the law. He was a criminal.” Indeed, there was a rank smell at Paramount in those days. Bluhdorn was under investigation by the Securities and Exchange Commission throughout the 70s, and Evans was close to Hollywood’s real Godfather, Sidney Korshak.

Before hiring Bob Evans at Paramount, Bluhdorn commented, “Thecaca in charge there now is ninety years old. He sawAlfieand couldn’t even hear it.”

Bluhdorn’s head of distribution was Frank Yablans. The son of a Brooklyn cabbie, he liked to say he graduated from the “Brooklyn Street Corner School of Economics.” He had a huge ego. “Frank had the biggest Napoleonic complex of anyone short of Napoleon,” says William Friedkin. But Yablans was tough, quick on his feet, and his sense of humor was wicked. He would think nothing of walking past a female employee and saying, “Nice tits today, honey.” But he was forthright, direct— you knew where you stood with him.

Bluhdorn’s 1966 hiring of Robert Evans had been a typically impulsive move. The novice executive had been an actor; he was devoid of qualifications. According to Evans’s predecessor, Howard W. Koch Sr., the future executive had cozied up to Bluhdorn’s French wife, Yvette. “He’s gorgeous,” she told her husband. “We’ve got to get a good-looking guy, real sexy, to run the company.”

Paramount accounted for no more than 5 percent of Gulf & Western’s revenues, and Bluhdorn may not have cared who ran it. He told Evans, “The Paramount caca in charge there now is ninety years old. He saw Alfie and couldn’t even hear it.”

Evans would one day crash and bum, but at 36 he had a permanent tan, his teeth dazzled, and his hair was as black as pitch. His voice, hoarse and gravelly, sounded as if he had swallowed ground glass. A dentist’s son, Evans had been born on June 29, 1930, and had worked in his brother’s clothing business. (When angry, Bluhdom called his production chief “that pants cutter.”)

Paramount bought Evans a house in Beverly Hills for around $290,000. He christened the place Woodland. The pool was egg-shaped; there were 100-foot eucalyptus trees, a centuries-old sycamore, more than 1,000 ornamental rose bushes—and high walls. Evans played tennis there with Jack Nicholson, Dustin Hoffman, Henry Kissinger, and Ted Kennedy.

Evans, who introduced Bluhdorn to women, liked female company—models, actresses, and other working girls. Often, in the mornings, when his housekeeper served breakfast in bed—black coffee and cheesecake—she put the girl’s name on a piece of paper under Evans’s plate to help him recall who she was.

On October 24, 1969, Evans wedded Ali MacGraw, the 31-year-old star of 1970’s Love Story. Bart didn’t like her. “Ali was one of these people who felt like she had to decorate herself like a 60s person,” he says. “She was about as much a 60s person as Leona Helmsley. She was materialistic, self-aggrandizing, and basically would fuck any actor she played opposite of.” On the surface, however, it appeared to be a storybook marriage, a pairing of handsome mogul and beautiful leading lady.

In the light of later events, particularly Evans’s addiction to cocaine, it is easy to underestimate him, but he was extremely effective for nearly a decade. “You have no idea what a great mind Evans was in those days,” says Friedkin.

Between Evans the pants cutter, the chemically imbalanced Bluhdorn, and the bullying Yablans, Paramount was a loony bin of big egos and bad tempers. But by 1971, Romeo and Juliet, The Odd Couple, Plaza Suite, Rosemary’s Baby, and Love Story had put the studio at the head of the Hollywood class.

The documentary Woodstock was such a hit for Warner that Fred Weintraub enlisted a bunch of hippie rockers who would drive across country and give concerts while a crew filmed their antics. Later, to recut the film, which was entitled Medicine Ball Caravan and released in 1971, Weintraub summoned Martin Scorsese, who was already known for his encyclopedic knowledge of film, and his tendency to spit out words like machine-gun fire.

Scorsese—small and long-haired—arrived from New York in January 1971, and immediately went into culture shock, “I had a really hard time adjusting to L.A.,” he recalls. “Driving, forget it.” The freeways terrified him. He used his Corvette—’60, white—on surface streets only. His asthma had worsened. “I never really got much sleep at night because of waking up coughing,” he remembers. “By the time I got past an attack in the middle of the night, took an asthma pill, and fell into a really deep, peaceful sleep, it was time to get up again. So I was always a little cranky.”

Scorsese used an inhaler for asthma. Said Don Simpson, “One hit, you were flying. I realized why he was so hyper.”

Scorsese was going up and down in weight, partly due to the medication he was taking for asthma. Said Don Simpson, who met him at Warner, “What he was taking was basically speed. . . . One hit, you were just flying. I finally realized why he was so hyper, because he had the inhaler to his nose day and night, which is why he could stay up for days on end talking about movies and music. He had this rock ’n’ roll head, knew every lyric and title. He understood music as a critical aspect of the Zeitgeist of the times.”

Brian De Palma, who would go on to create homages to Hitchcock such as Dressed to Kill (1980) and Obsession (1976), was one of Scorsese’s few friends in L.A. They had met at N.Y.U. in 1965. De Palma, 29, was already a legend to struggling filmmakers; he had several independent features under his belt, including Greetings (1968) and Hi, Mom! (1970), which featured an actor named Robert De Niro.

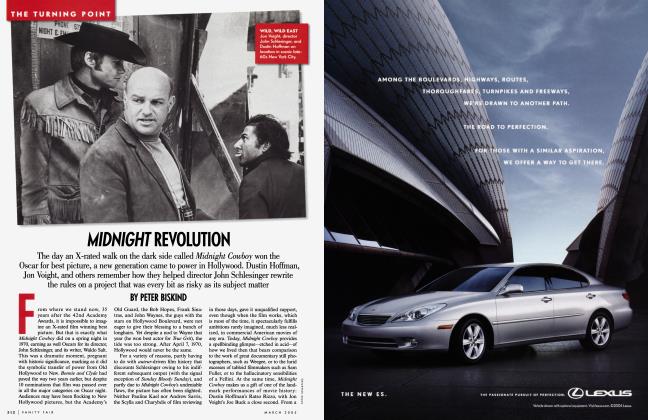

When Weintraub called De Palma in 1970 and asked him to direct a picture for Warner called Get to Know Your Rabbit, the director joined the exodus to L.A. He dropped in on Jennifer Salt, a young actress he had worked with. (She happened to be the daughter of blacklisted screenwriter Waldo Salt, who wrote Midnight Cowboy.) Salt was staying with Jill Clayburgh, who was doing Othello at the Mark Taper Forum. Salt recalls, “We were all sitting on the beach, and I said, ‘I’m going to move out here.’ Brian said, ‘Me too. Come on, let’s take this town by storm.’”

The day after Bluhdorn hired Coppola to direct The Godfather in 1970, .the director and his family celebrated by sailing for Europe on the Michelangelo with no more than $400 and Mona Skager’s credit cards. He commandeered the bar, broke down the novel, and pasted pages all over the windows.

After Coppola’s return, A1 Ruddy and his associate producer, Gray Frederickson, discovered that Coppola was not as tractable as they had thought. For the film, the director wanted to maintain the novel’s 1940s period setting, demanded a New York location shoot, and insisted on a bigger budget. Occasionally when Coppola finished a conversation with Evans, he pulverized the phone, beating it to pieces with the receiver.

Coppola didn’t care about marquee names. Evans did, and as the budget rose, Evans cared more. To him, Coppola was a nobody, a pisher. Evans attempted to call all the shots but found he was unable to impose all his whims.

According to James Caan, Coppola wanted Caan for Sonny Corleone, Robert Duvall for Hagen, and A1 Pacino for Michael. Pacino was anathema to Evans; he was unknown and short. Bluhdorn referred to him as “the Italian dwarf.”

Who would play the don? Coppola wanted Marlon Brando, but Stanley Jaffe vowed that the star, known for driving pictures way over budget, would not be cast as long as he was head of Paramount. At this point the director appeared to have an epileptic fit, and dramatically collapsed in a heap.

Lucas advised Coppola: “Don’t try to make this into one of your films. Just roll over and let them do it to you. Trying to win a game of poker with the Devil, they’ll crush you, and you won’t get the money you need to make the films we want.”

In the fall of 1970, Coppola had met Scorsese at the Sorrento film festival. Everybody said that Francis looked like Marty’s older brother. They became friends. In New York, Coppola dined at the table of Scorsese’s mother and father in Little Italy. “My father’s voice was recorded to listen to the accent,” Marty recalled. “My mother was constantly giving him casting suggestions. One night at dinner she told him she wanted Richard Conte in the picture, and he put him in. Another time, she asked him how many days he had to shoot, and he said, ‘A hundred days.’ She said, ‘That’s not enough.’ I said, ‘Mom, don’t get him terrified!’”

Eventually Coppola won the casting wars. “Four months later, after all this tension, I wound up with my cast, Brando and Pacino,” Coppola says. “If I hadn’t fought, I would have made a movie with Ernest Borgnine and Ryan O’Neal set in the 70s.” But Coppola was exhausted. Recalls Bart, “Evans made Coppola’s life miserable. He took up Francis’s preparation time shooting fucking tests. Francis didn’t have a chance to think about the movie, the locations.”

The Godfather began production on March 29, 1971. Says Steven Kesten, the original first assistant director, “Francis was at the bottom of the abyss.” Coppola struck the tough New York crew as indecisive. “Running a set means you gotta be the guy that makes it go forward,” says Kesten. “And it just wasn’t happening. Francis was always having to be nudged along.” During the scouting of a location on lower Fifth Avenue, Francis disappeared into Polk’s, a hobby store, and spent the afternoon buying toys.

By the end of the first week, Coppola was behind. He rewrote the script at night and between setups, creating chaos. Coppola recalls, “I was in deep, deep, deep trouble.”

Every morning he would close the set and rehearse until noon, letting the crew wait. This left only half a day for actual shooting.

Frederickson—after overhearing a conversation between Ruddy and Evanswarned Coppola that he was about to be replaced. But nobody wanted to be the one to fire him, and when he won the Academy Award for writing Patton, he somehow managed to talk Bluhdorn into keeping him.

Gordon Willis, director of photography on The Godfather, has said, “Francis’s attitude is like, ‘I’ll set my clothes on fire—if I can make it to the other side of the room it’ll be spectacular.’” Adds Willis, “You can’t shoot a whole movie hoping for happy accidents.”

Scorsese dropped by the set when Coppola was shooting the funeral of the don. He recalled, “Francis just sat down on one of the tombstones in the graveyard and started crying.”

After six months of shooting, The Godfather wrapped in September 1971.

The day arrived when Coppola, who had been editing in San Francisco, had to screen his cut for Paramount in L.A. Evans suffered from a bad back, and he had begun taking painkillers, among other drugs, for his distress. “He had a guy come in every day who gave him an injection of vitamins,” says Bart. “Who knows what it was.”

On the day of the screening, Evans’s butler, David Gilruth, wheeled him into the Paramount screening room on a hospital bed. He wore fine silk pajamas and black velvet slippers with gold fox tassels.

Evans claims that after seeing the cut he told Bluhdom, against Coppola’s wishes, that the picture had to be longer. “The fat fuck shot a great film,” Evans says he told Bluhdom, “but it ain’t on the screen.”

Friedkin poked his head through the sunroof of Coppola’s Mercedes 600 stretch limo and quoted a review ofThe French Connection.

Says Yablans, “Evans behaved very badly. He had everybody believing Coppola had nothing to do with the movie! Evans did not save The Godfather, Evans did not make it. That is a total figment of his imagination.”

Up to the end, Coppola believed he had a flop. He was living in Caan’s tiny maid’s room in L.A., sending his per diem to his family. One day he went with an assistant to see The French Connection, directed by Friedkin, which had just raved about the movie they had just seen. Coppola said, “Well, I guess I failed. I took a popular, pulpy, salacious novel, and turned it into a bunch of guys sitting around in dark rooms talking.”

“Yeah,” came the reply. “I guess you did.”

But when The Godfather was screened a week and a half later, Ruddy came out wreathed in smiles, saying, “Through the roof, baby, it’s gonna be a monster hit!” The film opened in New York on March 15, 1972, during an unseasonably late snowstorm. After the premiere, Coppola fled to Paris to write. His friends called, saying, “The Godfather’s a huge hit.” He’d answer, “Oh, yeah, great,” and turn back to his work.

By January 1973, only 10 months after it opened, The Godfather became the biggest grosser of all time. And not only did the movie revive Paramount with a tremendous infusion of cash, it was a jolt of electricity for the industry.

Some months earlier, Coppola, joking with Evans and Ruddy, had asked for a Mercedes 600-the big stretch limoif the picture hit $15 mil lion. Evans had replied, "No problem at $50 mil lion." Recalls Coppola, “When the picture had done a hundred million dollars, George Lucas and I walked into a Mercedes dealership in San Francisco and I said, ‘We want to see a Mercedes 600.’ The salesmen kept passing us along to other salesmen, because we had driven up in a Honda. They showed us a few sedans, and we kept saying, ‘No, no! We want the one with the six doors.’ So finally some young salesman took the order. I said, ‘Send the bill to Paramount Pictures,’ and they did.”

Truly the ugly duckling transformed into a swan, Coppola learned in time to appreciate the favors of women. “For a long time I didn’t want to be alone,” he recalled. “The romances . . . were pretty conventional, schoolboy kind of romances. ... I had a couple that were sort of the-most-beautiful-girlyou-ever-saw kind of things. All of us, when we’re young, have that fantasy.” Back in San Francisco, he began getting milliondollar checks in the mail from Paramount. “I was . . . one of the first young people to become rich overnight,” he said. Coppola had started to think of himself as Don Corleone. He even printed up matchbooks on which was inscribed “Francis Ford Coppola: The Godfather

Coppola was a boy at a table loaded with sweets; characteristically, he ate them all. The rush of power distracted him from the artistic ambitions he had held for so long. “It just inflamed so many other desires,” he explained.

Bogdanovich was a Sue Mengers client. “You underpriced baby,” she’d purr to her prey. "I'll get you your mil, honey.”

Coppola bought a run-down, robin’segg-blue, 28-room Queen Anne row house in San Francisco’s posh Pacific Heights with a breathtaking view of the Golden Gate Bridge. A Warhol Mao print hung in the dining room. One room was devoted to electric trains. (Friends dubbed him “F. A. O. Coppola.”) Another room contained a Wurlitzer jukebox full of rare Enrico Caruso 78s. A ballroom became a projection room with a Moog synthesizer, a harpsichord, and a collection of roller skates left over from You’re a Big Boy Now. Francis greeted guests in a caftan. Like a newborn porpoise, he splashed in his clover-shaped, Moorishstyle pool.

Coppola re-created Zoetrope as a more traditional production company and housed it in the Sentinel Building, which he had bought from the Kingston Trio. His top-floor offices, designed by Dean Tavoularis, were fit for a Renaissance prince, with windows on three sides, intricate handcrafted white-oak paneling, and inlay in the Art Deco style. A cupola ringed by a 360-degree mural depicted scenes from Coppola’s movies under a deep-azure sky painted by Tavoularis’s brother, Alex.

In the summer of 1972, agent Freddie Fields had a party that was attended by Coppola, Friedkin, and Bogdanovich. The first two left in Coppola’s new Mercedes 600 stretch limo. Coppola had a bottle of champagne, which he spritzed over the car. They were all well lubricated, driving along Sunset singing “Hurray for Hollywood.”

Bogdanovich had left the party at the same time, in a Volvo station wagon driven by his estranged wife, Polly Platt. By happenstance, the two vehicles pulled up alongside each other at a red light on the Strip. Friedkin stood and poked his head through the sunroof. Seeing Bogdanovich, he shouted, “The most exciting American film in 25 years!,” quoting a review of The French Connection. Holding up five fingers, he added, “Eight nominations and five Oscars, including best picture!”

Not to be outdone, Bogdanovich stuck his head out the window of the Volvo and recited a line from one of his reviews, which he had apparently committed to memory: “The Last Picture Show, a film that will revolutionize film history.” He added, “Eight nominations— and my movie’s better than yours!”

Coppola thrust himself through the sunroof and bellowed, “The Godfather, $100 million!” Platt thought, These three guys are acting like assholes, but they know it. This is the way Hollywood is supposed to be.

At the Academy Awards on March 27, 1973, The Godfather-with 10 Oscar nominations—won only three: best picture, best actor (Brando), and best adapted screenplay (Coppola and Puzo). Coppola lost best director to Bob Fosse, for Cabaret. Attired in a red tuxedo, Coppola thanked everyone but Evans, whom he “forgot.”

Evans was furious, but had other problems. One was clearly cocaine. Colleagues wondered why at meetings Evans was frequently seen rubbing his finger along his gums after putting his hand in his pocket. “I felt that he was abusing himself, and losing it,” recalls Bart. “There were too many crises.”

One was the Godfather sequel, which Puzo was already writing, despite Coppola’s refusal to direct it. Coppola wanted Martin Scorsese to do it instead. “I have no interest in the Godfather movies,” he said to Bart at a breakfast meeting. “I’m tired of— I do something that people want, that they love, they beg me to do it. Then they start attacking me, second-guessing me. That’s why I like to cook. You work hard in the kitchen, usually people say, ‘Ummm, that was good,’ not ‘There’s mildew on the rigatoni.’ ”

“Look, who was the star of The Godfather!” asked Bart, laying it on thick. “Brando? Pacino? . . . No, it was you. What does a star get?”

“A million,” replied Coppola.

“If I can get you a million to write and direct, will you do it?”

“O.K., you got a deal,” said Coppola, reinvigorated. Bart called Bluhdorn, who yelled, “Yes, yes, close da teal. Do id! Do id!” Adds Bart, “I think this was one of the times we couldn’t find Bob.”

As soon as news of the deal leaked out, Warner came after Coppola for the $300,000 he owed. “Warner hurt us in many ways,” the director says. “They threatened to put a cloud over The Godfather Part II unless they had their development money returned to them. They truly acted like an ‘evil empire.’”

Like Coppola, 33-year-old Peter Bogdanovich was thriving in the glow of the media spotlight that now surrounded successful directors. In New York, as a hungry young critic, Bogdanovich had attracted attention with his retrospectives on Hollywood directors held at the Museum of Modern Art. The programs, attended by many of the figures who would become New Hollywood mainstays, were influential. So were Bogdanovich’s monographs, which director Robert Benton, who cowrote the screenplay for Bonnie and Clyde, described as “the closest thing we had to a textbook.”

After The Last Picture Show and his blockbuster screwball comedy, What’s Up, Doc?, Bogdanovich was riding high and clearly intoxicated with himself. As a junior executive put it, “The first time I met him, it was as if I were in the presence of God. I had to introduce myself, and he wasn’t about to reciprocate and say his name. That might indicate that there was some doubt as to who he was.”

Bogdanovich’s agent was the very highprofile Sue Mengers, who had added directors to her roster of superstars, an indication of how prominent the men who made the films had become. “Oh, you underpriced baby,” she’d purr to her prey. “Your agent is keeping you down. I’ll get you your mil, honey.”

Her muumuus and rosetinted glasses contrasted sharply with Bogdanovich’s candy-striped shirts with white collars and occasional ascots. The atmosphere at Mengers’s parties was so heady that Bogdanovich’s girlfriend, Cybill Shepherd, was apprehensive about attending. Peter had to drag her by the arm up Mengers’s long driveway.

Bogdanovich’s marriage to Polly Platt, the brilliant production designer whose collaboration had been instrumental in the artistic success of his films, hit the rocks during filming of The Last Picture Show when Bogdanovich started his affair with Shepherd. They set up housekeeping in a 7,000square-foot hacienda, built in 1928, on Copa de Oro in Bel Air, just above Sunset. The hedges were neat, the pool crystalline. A Rolls-Royce was one of the five cars in the garage, although Bogdanovich hated to drive and once got lost inside the nearby U.C.L.A. campus when he tried to take a spin. One of his heroes, Orson Welles, was also in attendance, lodged in a bedroom-full of half-eaten dinners and cigar butts—off the study.

In early summer 1972, Coppola had called Bogdanovich to say that Charlie Bluhdorn had suggested starting a directors’ company. It was an innovation which marked the zenith of filmmakers’ power in the 70s. “We’d make pictures with complete autonomy, and eventually take [the company] public,” Bogdanovich recalls Coppola explaining.

Coppola and Bogdanovich played poker during the flight to New York to meet with Bluhdorn. Bogdanovich won $100 from his friend.

Friedkin, the third would-be member of the triumvirate, had never met Bluhdorn and was the first to arrive at the executive’s Essex House suite. Within moments Bluhdorn leaned over and sniffed Friedkin’s neck, asking, “Friedkin, vhat’s dat shit you’re verink?” “Guerlain.”

“Guerlain? Come here!” He led Friedkin into his bathroom, where he had every aftershave in the world, including a Baccarat cut-glass bottle of Guerlain. Opening it up, he poured some on his own shoes. “Dis is vhat I do to Guerlain,” he announced. “That was my introduction to Charlie, and he never got any saner as long as I knew him,” Friedkin recalls.

After the others arrived, Bluhdorn began: the partners could make any picture under $3 million without submitting so much as a Kleenex to Paramount, which offered to capitalize the new company to the tune of $31.5 million. Billy Wilder commented, “This deal should win an Oscar.”

But Bluhdorn had not yet told Yablans. Five minutes before a second meeting, Bluhdorn called his colleague. “You von’t belief vhat I’ve done, an impossible dream,” he barked. “I put togedder a company, a directors’ company, vid Francis, Friedkin, and Bogdanovich.”

“Oh, that’s great, that’s great, Charlie, have a good time with it.”

Later, Yablans joined the four men in Bluhdom’s office. “I think it’s shit,” he told them. “It’s the worst, stupidest, dumbest idea I ever heard in my life. Why don’t you just give ’em the company, Charlie?”

Yablans blamed Francis. “Coppola was playing Charlie like a Stradivarius,” he says. “Forty percent of the whole idea was probably his. He was passing himself off as ‘Poor little me, all I wanna do is make my films,” walking around in Puma sneakers and a corduroy suit, While he WaS flying in on Learjets and using stretch limos.”

CONTINUED ON PAGE 243

“It’s evil,” cried Scorsese as Spielberg coaxed him into the ocean. “Therms things with teeth. I don’t do the water.”

CONTINUED FROM PAGE 238

But on August 20, 1972, Yablans found himself at a press luncheon at ‘21,’ announcing the launch. “Coppola isn’t interested anymore in filming a pomegranate growing in the desert,” Yablans declared. He added that the three directors were “very commercial now.”

Coppola invited both Friedkin and Bogdanovich to San Francisco. According to Friedkin, Lucas served the food while the three others talked among themselves. “He was still Francis’s assistant, one of those guys hanging around him for scraps,” says Friedkin.

Indeed, as Marcia Lucas had predicted, Coppola had become the Bay Area’s one big fish, the source of all work and the fount of all pleasure. Alice Waters’s innovative Chez Panisse was his commissary, and his home was a nonstop party. Says Marcia, “Ellie used to be around for half an hour or so, and then she’d go upstairs with the kids, and Francis would be feeling up some babe in the hot tub. I was hurt and embarrassed for Ellie, and I thought Francis was pretty disgusting.”

Coppola’s first film for the Directors Company was The Conversation, about a detective who uses high-tech sound equipment, falls into a paranoid funk, and self-destructs. Friedkin hated it. “It was a very obscure rip-off of Antonioni’s Blow-Up,” he says. Bogdanovich agreed. “Francis said it was gonna be a Hitchcock kind of movie,” he grumbles. “It didn’t end up a Hitchcock kind of movie.” But they were not allowed to veto one another’s pictures.

On May 16, 1973, Paper Moon—Bogdanovich’s Directors Company debutopened to rave notices and lines at the box office. He was going from hit to hit, and becoming more insufferable all the time.

According to company bylaws, each director was entitled to a cut of the others’ pictures. Coppola took $300,000 of Paper Moon’s, profits, as did Friedkin, who had directed nothing. Yablans, who was looking for a chance to help destroy the amalgamation of the three big egos, says, “Once they took Peter’s money, it was over. I called Peter and said, ‘When are these guys going to make a movie? Christ! They have your money—what’s going on here?’ ”

Bogdanovich was furious. But he was looking for projects to do with Shepherd. Ever since actor Timothy Bottoms had given her the Henry James novella Daisy Miller, she had been set on starring in it. Now Bogdanovich was ready. “She’s so right for it—as though Henry James had her in mind when he wrote it,” he said, with typical modesty. Bogdanovich agonized over whether the credits should read, “A Peter Bogdanovich film of Henry James’s novella,” or “Henry James’s novella directed by Peter Bogdanovich,” or “Henry James’s Daisy Miller, a film by Peter Bogdanovich,” or “Peter Bogdanovich’s Daisy Miller, from Henry James’s novella.”

“The next thing I knew was that Peter was making Daisy Miller, starring his girlfriend, who had no discernible acting ability,” says Friedkin. “I thought, What the fuck is going on? Peter was just using this company as a vanity press. I reminded him that we had an agreement that we weren’t gonna take projects that no other studio would make and dump them into this company.

“The Directors Company was an amazing thing and it was ultimately destroyed in a Machiavellian way by Yablans. He even let Cybill record an album called Cybill Does It ... to Cole Porter, and he put up a gigantic billboard for it on the Strip, all of which was part of his design to undo the company. Frank knew that if he encouraged Peter along that path ...”

When Daisy Miller came out on May 22, 1974, it was killed by the same critics who had hailed Bogdanovich. One wrote that Shepherd was “a no-talent dame with nice boobs and a toothpaste smile and all the star quality of a dead hamster.” Daisy Miller was the last straw for the Directors Company. “Billy said he wanted out,” says Bogdanovich. “We said, ‘You haven’t even made a picture.’ The company didn’t work because Billy didn’t want it to go on.” Explains Friedkin, “I was not gonna put my next picture through a company that had a management trying to sabotage it. I withdrew.”

On Sundays, Fred Weintraub, the Warner executive who had advised George Lucas to put the freaks up front, had a regular open house. He entertained Hollywood hopefuls around his oversize water bed. During the summer of 1971, Brian De Palma went and Marty Scorsese went. One Sunday, just a few months after his dreams had been interrupted by the earthquake he had sworn was the Big One, Scorsese—by then divorced from his first wife, Larraine Brennan—ran into Sandi Weintraub. She was, as Don Simpson delicately put it, one of Freddy’s “big-titted daughters.”

They would live together for four years. “Marty was tempestuous, volatile, passionate,” Sandi says. “He breathed, ate, and shat movies. We never ever looked at a movie and thought, Oh, wow, what a great career move for him. I told him about my dreams, and he would tell me about the movie he had seen the day before.”

When Scorsese had moved to L.A., Brian De Palma introduced him to Jennifer Salt. She was making the rounds, looking for work and a place to live. One day she tested for John Huston’s Fat City. All the actresses wore the same dress, and when Salt pulled it over her head, the armpits were still moist from the woman before her. Her name was Margot Kidder. “It was so tacky,” recalls Salt. Kidder and Salt decided to go on a fast together and find a place to share. Donald Sutherland, the star of Robert Altman’s hit M*A *S*H, knew of a house on Nicholas Canyon beach.

Kidder and Salt’s lopsided A-frame was unfashionably far from the action, up the Pacific Coast Highway past Malibu. Tom Pollock, an attorney, had a shack there; actress Blythe Danner and producer Bruce Paltrow lived nearby. Producers Michael and Julia Phillips would move in next door, and writers John Gregory Dunne and Joan Didion lived up on the hill. The SaltKidder house, not to mention Salt and Kidder themselves, became a magnet for young Hollywood, a place where the aspiring artists could take a few tokes, drink red wine, trade John Ford stories, and stare at Salt, Kidder, and Salt’s chum Janet Margolin sunbathing topless.

Salt was the princess from Sarah Lawrence. Kidder, from a considerably more declasse background, had moved from one remote town to another. She was cute and scrappy, funny, a tomboy, and enormously bright. Salt taught her how to dress. Kidder slept with nearly every man who crossed the threshold. She moved from crisis to crisis, broke hearts, and sued a producer. And she did drugs like they were going out of style.

“I cooked for the boys,” Jennifer Salt recalls, “gave parties, made them take drugs and take their pants off.”

“Out of the drug taking,” Kidder says, “came a lot of creative thinking and breaking down of personal barriers and having a phony social persona. If that hadn’t been the case, none of us would have developed our talents. But Steven Spielberg didn’t take drugs, Brian didn’t, Marty didn’t, until later when he got into trouble with coke. The directors who ended up successful were very protective of their own brains.”

Margie—with a hard g as she pronounced it—started seeing De Palma. They were passionately in heat, making it anywhere and everywhere, once in a closet during a party. At the time, Bobby Fischer was challenging Boris Spassky, and a chess craze had swept the beach. Brian taught Margie to play and would upset the board when she made a dumb move.

De Palma brought friends over, and Salt found herself cooking for him, Scorsese, Spielberg, screenwriters John Milius and David Ward, director Walter Hill, as well as actors Peter Boyle and Bruce Dern and others. They grilled steaks, ate spaghetti, tossed salads. Recalls Salt, “I cooked for these boys, gave lots of parties, made them take drugs and take their pants off and get down.”

Nicholas beach was isolated; the only rules were the ones they made for themselves. If you wanted to be cool, you had to go skinny-dipping, which was especially hard on Scorsese, because the prednisone he took for his asthma had made his body blow up. He would sit on the sand fully dressed. Steven Spielberg, who didn’t much like the water himself, would say, “C’mon, let’s go in.”

“No, no, no, it’s very bad, it’s evil. There’s things out there you don’t even want to know about . . . things with teeth. I don’t do the water.”

Scorsese had an old-world courtliness about him that endeared him to Kidder and Salt. One day he appeared in an immaculate white suit with a bouquet of flowers for each. Says Kidder, “Marty loved people trying new things, loved bravery of personal expression, and talked about it very eloquently, albeit very quickly. I don’t remember many silly talks with Marty.”

Recalls Scorsese, “The period from ’71 to ’76 was the best period. We couldn’t wait for our friends’ next pictures—Brian’s next picture, Francis’s next picture—to see what they were doing. Dinners in Chinese restaurants midday in L.A. with Spielberg and Lucas. My daughter named one of Steven’s movies Watch the Skies.” (Spielberg renamed the film Close Encounters of the Third Kind after that.)

After THX 1138 flopped, George Lucas was at something of a crossroads. Coppola advised, “Don’t be so weird, try to do something that’s human. All you do is science fiction. Everyone thinks you’re a cold fish. Make a warm and funny movie.” Marcia was on his case, too. “After THX went down the toilet, I reminded George that I warned him it hadn’t involved the audience emotionally,” she recalls. “He always said, ‘Emotionally involving the audience is easy. Anybody can do it blindfolded—get a little kitten and have some guy wring its neck.’ All he wanted to do was abstract filmmaking. So finally George said to me, ‘I’m gonna show you how easy it is. I’ll make a film that emotionally involves the audience.’”

Lucas recognized that Hollywood was ignoring an audience that was tiring of the steady diet of sex, violence, and pessimism doled out by the New Hollywood. “Before American Graffiti, I was working on basically negative movies,” he said. “I became very aware of the fact that... the heritage we built up since the war [W.W. II] had been wiped out in the Sixties, and . . . now you just sort of sat there and got stoned. I wanted to preserve what a certain generation of Americans thought being a teenager was really about. . . from about 1945 to 1962.”

He wanted to make a film about something he knew intimately, teenage rites of passage in a small town in the 50s—the hot rods, the top-10 musical wallpaper that was background for everything from drag racing to heavy petting. He set the plot in the early 60s, on the eve of the Vietnam War.

American Graffiti was an ensemble piece focusing on four young men. There was precious little in the way of plot. When Lucas’s agent, Jeff Berg, sent his script to the studios, most of them turned it down. Bart was one of the executives underimpressed by Lucas. He thought, I can’t imagine George directing a movie, because he’s so noncommunicative, the ultimate passiveaggressive. Finally, Universal showed interest. Production executive Ned Tanen was intrigued by Lucas’s tale of nerds on wheels.

Tanen felt that Lucas needed a good producer. Coppola, whom Tanen often ridiculed as “Francis the Mad,” was the logical choice. Tanen gave Lucas a list of acceptable producers to choose from and Lucas immediately put a check next to Coppola’s name. He wasn’t too happy about it; he had been determined to go out on his own, but it seemed all roads led back to Coppola, who agreed immediately.

Coppola persuaded his old friends from Zoetrope Willard Huyck and Gloria Katz to work on the script. “Francis got the movie made,” says Huyck. “George would be at the airport, and he’d see two guys arguing, and he’d say, ‘They’re the exact people I want for my movie,’ so he’d bring them in and Francis would say, ‘George, I think we need real actors.’”

American Graffiti was shot in 28 days, starting in the last week of June 1972. Lucas was worried about directing the actors. He hadn’t the foggiest idea what to say to them. Finally, he hired a drama coach to work with them, while he confined himself to the camera. When Tanen made one of his infrequent visits to the set, Lucas ignored him. “George has no social graces,” says Katz. “And in his psychology, the suits had no business other than writing the checks. He didn’t want to hear what they said, he didn’t respect them.”

Film editor Verna “Mother Cutter” Fields, along with the Lucases, assembled what became American Graffiti in the garage of a house owned by Coppola in Mill Valley. On the Moviola, Coppola had taped Xeroxes of milliondollar checks from Paramount for The Godfather.

Scorsese was still struggling. “I was an opportunist,” he says. “I went to every party, talked to everybody I could to get a picture made. I looked at people in terms of whether they could help me. I had my own agenda. I was obsessive, relentless, ruthless.”

“Emotionally involving the audience is easy,” said George Lucas. “Get a kitten and have some guy wring its neck.”

Sandi took care of him, was a nurse, mother, and lover. “He needed a lot of attention,” she says. Scorsese was filled with phobias and anxieties, and he began to see a therapist. He hated to fly, and during takeoff and landing he gripped a crucifix in his fist until his knuckles turned white. He was beset by superstitions, a melding of Catholicism and some arcana of his own making, forebodings drawn from dreams, signs, and portents of various kinds. He had an unlucky number, 11. He and Sandi lived in a building with numbered parking spaces. When the digits on a space added up to 11, he would walk around it. He wouldn’t travel on the 11th of the month, avoided flights with the number 11, and wouldn’t take a room on the 11th floor of a hotel. He had a gold amulet to ward off evil spirits, and carried a leather pouch filled with lucky charms in his pocket. Once, he lost the pouch and freaked out. Sandi had to buy more charms and fill a new pouch with them.

Scorsese needed Sandi, but the two fought constantly. “He got angry once and swept off the table with his arms and a glass went flying, and I was naked and I got some glass in my back. He never attacked me or hit me, but he was a wall puncher. And a phone thrower.”

Weintraub thinks that some of Scorsese’s rage came from his father. “I remember his parents coming to visit, and his father said, ‘Are you still seeing that funny doctor,’ the therapist? And Marty said, ‘Yeah, it’s really helping me.’ His father’s face got really red and angry. He said, ‘When are you gonna grow up and be a man?’ ”

Around the middle of 1971, Roger Corman gave Scorsese the chance to direct Boxcar Bertha. A variation on the themes of Warren Beatty’s controversial Bonnie and Clyde, it was a Depression-era drama about a persecuted union organizer (David Carradine) and a boxcar-riding bimbo (Barbara Hershey). Said Don Simpson, “Roger, I swear, didn’t know what picture Marty was making. All he cared about was ‘Is Barbara gonna, like, show tits?’ ”

Scorsese was embarrassed by the film. He showed it to John Cassavetes, who said, “Nice work, but don’t fucking ever do something like this again.”

While Scorsese’s agent, Harry Ufland, shopped around Scorsese’s next project, Mean Streets (then titled Season of the Witch), Scorsese revised and revised the script. Film critic Jay Cocks, Scorsese’s friend and occasional writing collaborator, renamed it, borrowing a phrase from Raymond Chandler. Cocks’s wife, Verna Bloom, an actress, introduced Scorsese to Jonathan Taplin, an ex-road manager for Bob Dylan and the Band. Taplin told Scorsese he could raise the money to produce it.

Scorsese met Robert De Niro at a dinner party. As it turned out, they had grown up within a few blocks of each other and hit it off immediately.

De Niro, who was very serious about acting, didn’t hang out, didn’t make small talk. He was so shy that it was hard for him to get work. “You couldn’t get De Niro arrested,” recalls casting director Nessa Hyams. De Niro read Mean Streets and eventually agreed to play the character of Johnny Boy, the “funny in the head” neighborhood nut. Harvey Keitel would play Charlie, the Scorsese surrogate, a character tom between the church and the Mob.

Most of the movie’s interiors were shot in L.A. in the fall of 1972. (The exteriors and some other key scenes had been shot earlier, during six days in New York.) “In order to get the picture made I had to learn how to make a movie,” says Scorsese. “I didn’t learn how to make a movie in film school. What you learned in film school was to express yourself with pictures and sound. But learning to make a movie is totally different. That’s the people with the production board, the schedule. That means you gotta get up at five in order to be there, you gotta feed the people.”

After a screening of the rough cut of Mean Streets, Sandi, Scorsese, De Niro, and a few others repaired to a restaurant for what Weintraub assumed would be a group dissection of the film. But De Niro and Scorsese disappeared into the men’s room for two and a half hours and hashed it out between themselves. Says Weintraub, “What Marty and Bob did together, they did in private. Definitely no women allowed.”

Helping one another was a deeply ingrained habit among New Hollywood filmmakers. Nevertheless, the flames of competitiveness burned hot and deep, if not all that visibly. As Scorsese puls it, “There was always a fine line, where maybe one person was getting more attention than the other. But if the person who's getting less attention sees your rough cut, he could steer you in a negative way on purpose. Without even knowing it. Because of the jealousy.”

“Brian never believed he was as successful as Francis or George. That made him very uncomfortable,” adds George Litto, who produced for De Palma later in the decade. De Palma advised Scorsese to get rid of one of the best scenes in Mean Streets, the improvisation between De Niro and Keitel in the back room of the club. He said. “It's just wasting time. Take it out.” Scorsese did, but Cocks told him to put it back, and he did.

Ameriean Graffiti previewed in Lucas territotry, at the Northpoint Theater in San Francisco, on January 28, 1973. Tanen flew in, but appeared to be in a black mood.

Tanen discounted the audience's extremely positive response. This place, he thought, is filled with Lucas’s friends. He cornered producer Gary Kurtz and told him, “This film is in no shape to show to an audience. You should have shown it to us first. I went to bat for you, and you let me down.” Wheeling around to face Coppola, he continued, angrily, “I’m very disturbed. We have a lot to do.”

“What are you talking about?"Coppola asked, his voice shaking with anger. “Didn't you just see and hear what we all just saw and heard? What about the laughter?”

“I've got notes. We'll have to see if we can release it.”

“You'll see if you can release it?” roared Coppola, apoplectic. “You should get down on your knees and thank George for saving your job. This kid has killed himself to make this movie for you. And he brought it in on time and on budget. The least you can do is thank him for that.” Coppola recalls whipping out a checkbook, and offering to buy the picture from Universal on the spot, saying, “If you hate it that much, let it go, we’ll set it up someplace else and get you all your money back.” Tanen abruptly dashed to his limo and left for the airport. He thought Coppola was grandstanding.

After it was all over, Lucas called Huyck and Katz, devastated. He said, "I don’t know what to do, this picture—people are responding off the wall, and they keep telling me they're going to put it on television.” But he was pleased with Coppola. He says now, “Francis really stood up to Ned. I was pretty proud of him.”

American Graffiti opened on August 1, 1973. It broke house records, and ultimately earned a phenomenal $55,123,000 in rentals. The picture's direct cost was $775,000. plus another $500,000 for prints, ads, and publicity—a 4,300 percent return on the investment. “To this

day, it's the most successful movie ever made,” Tanen now bombastically claims. Lucas's cut came to about $7 million, $4 million after taxes. For years, the Lucases had lived on a combined income of $20,000 a year or less. Yet for Lucas, who made few significant changes in his lifestyle, the glass was still half empty. Says Marcia Lucas, “He had this idea of being a flash in the pan: you hit it once and that's all you're ever going to have.” They did buy and restore an old Victorian in San Anselmo. Marcia called it Parkhouse. George was only 29 years old.

Lucas still wanted to be taken seriously as an artist, like Coppola and Scorsese. He told Billy Friedkin that American Graffiti was an American version of Fellini's I Vitelloni, and he wondered why none of the critics had picked up on it. Friedkin thought. My God, that’s what this guy really thinks he's done? He's filled up with himself.

After Mean Streets was completed, Scorsese got on a plane and went up to San Francisco and showed Coppola a print. “That's when Francis saw De Niro,” Scorsese recalls. “And immediately he put him in Godfather II."

Scorsese found Coppola enveloped in a cloud of sycophants who were fiercely jealous of outsiders. One, says Sandi Weintraub, would follow two steps behind him into the bathroom. “I don’t think Francis could fart without him catching it,” Weintraub says.

After a screening of Mean Streets, De Niro and Scorsese disappeared into the bathroom. “What they did together," says a friend, “they did in private. Definitely no women allowed.”

Scorsese and Taplin took Mean Streets to Cannes in May. “Marty, Bobby, and I were introduced to Fellini,” recalls Taplin. “When his distributor came into the room to pay homage to the maestro, Fellini said, ‘Ah, you should buy his film, it’s the greatest American film in the last 10 years.’ He hadn’t even seen it.”

With a potential foreign sale, Taplin was in an expansive mood. He invited everyone for lunch to Le Moulin de Mougins, a four-star restaurant in the hills above Cannes. De Niro was there, with his female companion of the moment. “Bobby always had girlfriend trouble,” says Taplin. “He picked these incredibly strong girls, top chicks, always black, and then he’d fight with them all the time. They would always be in tears the next morning, and he would buy them some perfume.”

Scorsese, Weintraub, and De Niro and his girlfriend were in the middle of an extraordinary meal when a bee the size of a small hummingbird buzzed the table. Sandi tried to ignore it, but finally called the waiter over and asked him to do something. The waiter flicked his towel at the bee, which dropped stone dead into De Niro’s girlfriend’s water glass. She became hysterical, exclaiming loudly, “He killed the bee! A living thing! I can’t believe this guy killed the bee!”

“Will you can it?” said De Niro, annoyed.

“What do you mean? You’re gonna just let him kill this bee?”

“It’s just a fucking bee! Will you shut the fuck up?”

“Why are you talking to me like that?” They started screaming. Finally De Niro said, “Why don’t you take a fucking hike?”

Mean Streets premiered at the New York Film Festival in the fall of 1973. “We were broke, beyond broke, really busted,” remembers Sandi. “Harry Ufland gave me his credit card so I could buy one skirt for the interviews, and I had to wash it every night, iron it on the floor. The night it opened was one of the most exciting events of my life. Marty got a standing ovation.”

Pauline Kael was enthusiastic in The New Yorker. “Martin Scorsese’s Mean Streets is a true original for our period, a triumph of personal filmmaking,” she wrote, and called it “probably the best American movie of 1973.” But Mean Streets didn’t exactly burn up the box office. Says Taplin, “Warner did a terrible job distributing Mean Streets. We made bubkes.”

'When I first heard about Steven Spielberg, he was already a Hollywood guy, absolutely part of the system without even a second thought, not a drop of rebellion in him,” says screenwriter Matthew Robbins, who became a close friend of the young director’s. “The sensibility of the work was always the most conservative. One of the TV things he made was a rip-off of THX, all these people running around in white pajamas in tunnels through a long lens. George Lucas used to grump about the fact that some Hollywood slickie had ripped him off for a TV show. We were all appalled. Who could it be? It was Steven!”

Like Scorsese, Spielberg had lots of phobias—fear of elevators, roller coasters, airplanes, and so on. If anyone looked at him sideways, he got a nosebleed. You name it, he was afraid of it. He had no interest in anything but movies—not art, books, music, politics. Screenwriter Kit Carson ran into him at a party in the fall of 1968 right after the Democratic convention. “Everybody was up, the revolution was about to happen—burn it all down—that sort of thing,” he remembers. “All Steve was interested in was trying to figure a way to throw a camera off a building and rig it with gyroscopes so that it wouldn’t spin out of control as it went down. . . . I said, ‘This kid’s fucked. He’s lost in the ozone, talking about the Twilight Zone.’”

Spielberg, who had spent several years directing television, had met Lucas, who had taken him to Coppola’s office at Warner. “I saw in Francis’s eyes somebody who did not distinguish between old and young, simply between talented and not,” Spielberg recalls. “He was producing for George, and to be in his circle meant a chance to direct a movie. You thought, Maybe here’s somebody who’s going to open it up for all of us. But he only opened it up for George. In Francis’s eyes, and also in George’s, I was an outsider working inside the system.”

Spielberg directed Duel, a movie-ofthe-week, for Barry Diller at ABC. It aired November 13, 1971, and got a lot of notice. Recalled Don Simpson, “The media were saying all these things about this kid who made Duel, and then Marty and Brian would say, ‘Well, what he did wasn’t so extraordinary.’ There was a little envy.”

In 1973, Spielberg directed The Sugarland Express, with Goldie Hawn. In most cases it is the producer who pressures the director to make his picture more commercial. In this instance, Spielberg suggested that the film might make more money if the main characters survived in the end. Producers David Brown and Richard Zanuck vetoed the idea.

After Duel, Spielberg had started making the trek to Nicholas beach. “Sometimes everybody slept in sleeping bags on the floors,” he recalls, “or on the beach on warm nights. It was as if a kind of movie-brat wave was starting to amass out at sea. One day I got there late, walked onto the beach, and everybody was buried in the sand, just these heads sticking out. It was like they had become future lobby cards, head shots.”

Spielberg gawked at the topless trio— Salt, Kidder, and Margolin. “I had never seen anything like that before,” he continues. “Even my sisters covered up. It was the first time I really felt connected with the flower-child generation.”

Spielberg, who was emotionally still a teenager (he subsisted on Twinkies and Oreo cookies, slept in white crew socks and white T-shirts), was smitten with Kidder, although they never actually had an affair. “We were out at Stanley Donen’s beach house, and Steve showed up with Margot,” recalls Willard Huyck. “She was wearing this white flowing dress. We looked over, and she was lying next to him on the sand, but she had pulled the dress all the way up so she could tan herself. She didn’t have any underpants on. Steve went beet red. He went, ‘Margot!’ He was really embarrassed.”

Spielberg was just desperate to be cool, friends recall. He wore “ridiculous pants with thousands of zippers.”

Spielberg immediately attached himself to De Palma, a lady-killer with attitude to spare. Spielberg appreciated both qualities. He started wearing a safari jacket, De Palma’s trademark garb. Eventually, he moved on to Scorsese, listening to him with the same rapt attention with which he absorbed De Palma’s opinions. Auteurism was foreign to Spielberg; the idea of movies as personal expression was novel. “He didn’t want to be the son of Jean-Luc Godard,” recalls Carson. “He wanted to be the son of Sid Sheinberg. He was just so different from Coppola and Scorsese and John Milius.” Adds Milius, “Steven was the one who ran out to buy the trades. He was always talking grosses.”

Remembers Kidder, “That was why Steven was in awe of them. He was more innocent of spirit and less complicated than Brian or Marty. He was much more normal than we were. Whatever trauma he went through because his parents got divorced he adjusted well to. He was never addicted or excessive. With Steven, what you saw was what you got.” He didn’t even do drugs. “I never took LSD, mescaline, coke, or anything like that,” he said. “But I went through the entire drug period. ... I would sit in a room and watch TV while people climbed the walls.”

Kidder tried to see to it that Spielberg didn’t embarrass himself, but it was difficult. He was just desperate to be cool, but he didn’t know how. He bought cowboy boots, perhaps to make himself seem taller, and was the kind of guy who wore bell-bottom blue jeans with a crease. “They had thousands of zippers,” recalls Huyck. “They were the most ridiculous-looking pants.”

Spielberg dedicated himself to parsing the culture. “Every month he read all the magazines, from Tiger Beat to Esquire to Time to Playboysays Milius. “He wanted to become an expert on what was hip, how people were thinking.”

Spielberg had little experience with women, and when he finally got a girlfriend, a stewardess he met while he was doing The Sugarland Express, Kidder taught him about the birds and the bees: “I sat him down and went, ‘O.K., Steven, here’s how you do it—you don’t wear your socks and your T-shirt to bed. Get something besides the Twinkies in the fridge, and read her Dylan Thomas.’ ”

While The Conversation was in postproduction, Coppola left the Bay Area to begin Godfather II, which commenced principal photography on October 23, 1973, in Lake Tahoe. The shoot was an ordeal for Eleanor Coppola, who cried a lot. She later wrote that her life was complicated by the “fresh crop of adoring young protegees waiting in the wings” for her husband. Francis Coppola had known Melissa Mathison, who would later earn an Oscar nomination for writing E.T. and marry Harrison Ford, since she was a kid of 12. He had watched her grow up into a tall woman— about five feet eight. She was thin, flatchested, and flashed a lot of gum when she smiled, but she was also droll and self-assured. She worshiped Coppola and he used to say, “She’s the greatest thing in bed I’ve ever had.” The liaison, however, displeased Coppola’s parents, who were sometimes on the set.

When the production got to New York, Sixth Street between Avenues A and B was dressed to look like the 20s. Coppola wanted to be able to, say, talk to the cinematographer three blocks away, so he had the street wired for sound. One day, according to Gray Frederickson, he got into a fight with his parents over Mathison. “What do you mean carrying on with that girl?” yelled Italia Coppola. “I’ll carry on with anyone I want to carry on with,” retorted Coppola, furious. “It’s none of your business. I’m a grown man!” The sounds of this battle were carried over the speakers, to the amusement of the crew.

In 1973, Richard Zanuck and David Brown paid $175,000—pre-publication —for the movie rights to Jaws, a novel by Peter Benchley. Spielberg, looking for something to do, was hanging out in Zanuck’s office one day in June of 1973. As Spielberg has told the story, “[I] swiped a copy of Jaws in galley form, took it home, read it over the weekend, and asked to do it.”

Recalls Spielberg, “In Francis’s eyes, and also in George’s, I was an outsider working inside the system.”

But after Zanuck and Brown gave him the nod, Spielberg developed reservations, which he expressed at a dinner with Brown and his wife, Cosmopolitan editor Helen Gurley Brown, at the Spanish Pavilion in New York. He worried that the project was too commercial. Spielberg recalls, “I didn’t know who I was. I wanted to make a movie that left its mark ... on people’s consciousness. I wanted to be Antonioni, Bob Rafelson, Hal Ashby, Marty Scorsese. I wanted to be everybody but myself.”

“There are two categories, films and movies,” Spielberg explained. “I want to make films.”

“Well, this is a big movie, a big movie,” Brown replied. “It will enable you to make all the films you want!”

When The Sugarland Express came out in April of 1974, the reviews were enthusiastic. Kael called Spielberg “a born entertainer” and his movie “one of the most phenomenal debut films in the history of movies.” But, despite the accolades, the picture flopped.

Spielberg wanted a hit. He thought that Jaws could be reanimated with a New Hollywood approach. But he didn’t much like Benchley’s script. He said that when he read the book he rooted for the shark. There had to be people to root for. He asked John Byrum, a kid who had just gotten into town, to do a rewrite. Byrum recalls, “Steven was sitting on the floor of his bungalow playing with a toy plastic helicopter. Battery-operated. It flew around in circles. I start telling him my notions about the script, and he said, ‘Oh, great idea!’ Like a 12-year-old. Then he said, ‘I gotta have my think music on,’ so he put on this James Bond album soundtrack.”

After Byrum passed on the project, Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright Howard Sackler wrote a draft that solved some problems, but by no means all. With the beginning of principal photography only weeks away, Spielberg persuaded Zanuck and Brown to hire his friend screenwriter Carl Gottlieb. He also secured the services of Verna Fields. She was a great favorite of Tanen’s, and Spielberg may have thought she could protect him from the kind of problems Lucas had encountered with the executive during American Graffiti. Spielberg was certainly not above such calculations. He had hired Lorraine Gary, Mrs. Sidney Sheinberg, to fill the small part of Roy Scheider’s wife, a bold move, politically.

Although Spielberg had welcomed big-time celebrity Goldie Hawn to The Sugarland Express, the star had failed to boost the picture’s take at the box office, and this time he resisted when the studio suggested Charlton Heston and Jan-Michael Vincent as stars who could sell Jaws. Said Spielberg, “I wanted somewhat anonymous actors to be in it so you would believe this was happening to people like you and me.” Zanuck and Brown suggested Robert Shaw, who had played in The Sting, for Quint. Richard Dreyfuss, a struggling actor who is reputed to have carried a scrap of lined yellow notepaper in his back pocket bearing the names of all the casting directors who had ever rejected him for a role, turned down Jaws at first. “Then I saw The Apprenticeship of Duddy Kravitz, and I was just so freaked out, I thought my performance was so terrible, that I called Steven and begged for the job. We started the film without a script, without a cast, and without a shark.”

At some point during pre-production, Spielberg took his friends Lucas and Milius to see the shark in progress in a hangar in North Hollywood. When he agreed to do Jaws, Spielberg thought he could just hire a shark wrangler to make a great white do a few pirouettes in the water. That proved to be wishful thinking, to say the least, and now he was faced with this giant creation, dubbed “Bruce” after Spielberg’s lawyer, Bruce Ramer.

The polyethylene cast was half done, unpainted, just a gray, submarine-like phallic thing with patches on the side, about 26 feet long. It was so large that Milius said, “They’re overdoing it.” Spielberg replied, “No, they aren’t, the ichthyologist said this is exactly what it would look like.” Milius got excited and said Spielberg was making the ultimate aquatic samurai film.

Lucas regarded the storyboard, looked up at the big shark, and said to Spielberg, “If you can get half of this on film you will have the biggest hit of all time.” Spielberg, meanwhile, grabbed the controls and made the enormous mouth open and shut with a grinding noise, like an outsize bear trap. Lucas climbed the ladder, waited for the jaws to part, and stuck his head inside.

Spielberg closed it on him. Milius thought, My God, we’re like human tacos compared with that thing. Spielberg tried to open the mouth, but it was stuck. After Lucas managed to extricate himself, the filmmakers jumped into the car and split. They knew they had broken something that cost a lot of money.

After six months in pre-production on Jaws, Spielberg was ready to pull out. “I stayed up at night fantasizing about how I could get myself off this picture short of dying,” he says. “I was out of my mind for a while. So I went to Sheinberg and Zanuck and Brown and said, ‘Let me out of this film.’ Dick pulled me aside and called me a knucklehead, said, ‘This is an opportunity of a lifetime. Don’t fuck it up.’ And Sid said, ‘We don’t make art films at Universal, we make films like Jaws. If you don’t want Jaws, you should work somewhere else.’ ”

On May 2, Spielberg was ready to begin. The budget was $3.5 million.

Watching the first rushes was “like a wake,” recalled De Palma, who was visiting the set. “Bruce’s eyes crossed, and his jaws wouldn’t close right.”

On the third day, one of the three sharks sank. The crew took to referring to the movie as “Flaws.” The production shut down several times to accommodate repairs on the sharks. Delay followed delay. Spielberg was lucky if he got one shot in the morning and another in the afternoon.

As Roy Scheider puts it, “We had so much time that we became a little repertory company. You had a receptive director and three ambitious, inventive actors. Dreyfuss, Shaw, and myself would have dinner and improvise scenes. Gottlieb would write them down, and the next day we would shoot. In a strange way, the inability of the shark to function was a bonus.”

Spielberg was under an enormous amount of pressure. He brought his own pillow with him from home and put celery in it, a smell he found comforting. He had no time for anything but work.

The final budget for Jaws was about $10 million. “It was a Schande" said Spielberg, “a scandal for the neighbors, meaning Mr. Sheinberg and Mr. Wasserman.”

As Spielberg fell farther and farther behind, the budget kept creeping up. Worse, the studio was unhappy with the dailies. At one point, Sheinberg arrived at the film’s Martha’s Vineyard location from L.A. He had dinner at Spielberg’s house, and afterward the director excused himself and went off into a corner with Gottlieb to work on the script. Sheinberg thought, My God! This is the way this is being done?

The next day, Sheinberg watched Spielberg shoot. During a break, Sheinberg took the opportunity to say, “I will back you in [either of] two decisions. If you want to quit now, we will find a way to make our money back. If you want to finish the movie, you can.”

Spielberg wanted to stay.

Shooting on the Vineyard ended in early October 1974. The original 55-day schedule had metastasized into 159 days, five and a half months. The final budget was about $10 million, an overage of more than 150 percent. Spielberg was humiliated: “It was a Schande, a scandal for the neighbors, meaning Mr. Sheinberg and Mr. Wasserman.”