Sign In to Your Account

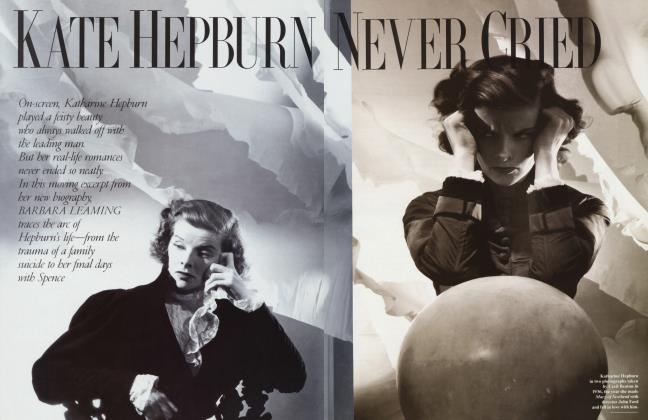

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

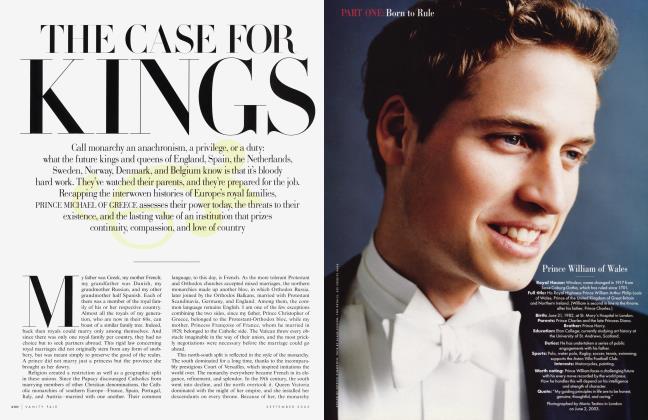

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowTHE CHOSEN ONE.

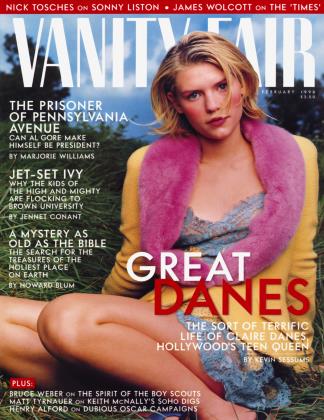

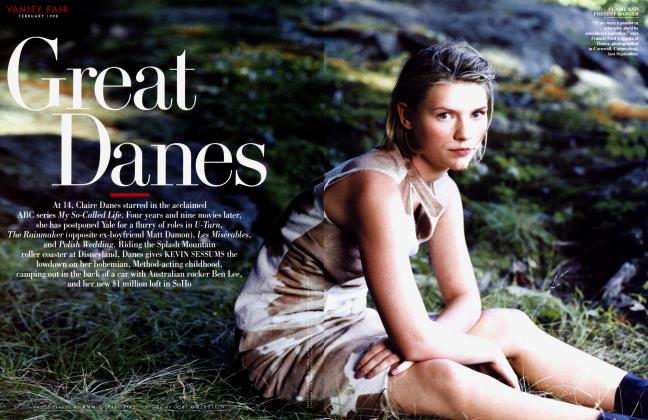

Essentially raised to become president, Albert Gore Jr. is one of the most disciplined and calculating politicians in the United States. And he may have the strongest sense of duty of any man in Washington. So why is the vice president starting into the 2000 campaign covered with Clinton's fund-raising mud? Gore's first problem, MARJORIE WILLIAMS discovers, is that there is a difference between doing his duty and doing the right thing. His second problem is his apparent contempt for his chosen career

It's true, what everyone says about A1 Gore. There is another Gore, a man funnier, more relaxed, warmer, happier than the very formal politician who serves as the 45th vice president of the United States. He has a dry sense of humor, that Gore; he wears Nike running shorts, and flipflops on his oddly chunky feet, and he drinks beer. He uses four-letter words, and has the explosive, facereddening laugh of a self-conscious teenager. That Gore, who stands with some grace on the verge of turning 50, has worked hard at understanding himself and his strange, boxed life as a boy and then a man who was channeled by powerful forces of love and tradition and sorrow and duty to the office he now occupies.

And then there's this guy: CarefulMan, whose signatures are a blue suit and white shirt, a pair of shiny wing tips, a studied frown of concentration. CarefulMan begins a recent Wednesday on a dais at a Goodwill Industries storefront office in the bleakest part of Orlando, Florida, flanked by officials and beneficiaries of a program designed to help its clients find and keep jobs.

From the start, he's a portrait in stone: uncomfortable, unconsciously condescending, and so rigid in his bearing that he might be wearing a neck brace. "The number of people on welfare in this country is now below 4 percent for the first time since way back in 1969," he says. Only why is he talking so slowly? "The president has negotiated and signed what are called wai-vers for 43 states ..." He is addressing this group of 50-odd adults in the tone of a pre-school teacher reasoning with three-yearolds, as if poverty made you stupid.

The bulk of the event involves Gore's asking questions—gleaned from a stack of file cards he carries with him—of the men and women who sit with him at the front of the room. One man offers a self-description that is apparently not as wretched as the cue cards suggest it should be: when he has finished, Gore prompts clumsily, "You were actually homeless, and you had other problems, and you were really kind of flat on your back for a while there, weren't you?"

In truth, Gore spends most of the event doing and saying the right things. He nods in the right places, furrows his handsome brow, and now and then makes little murmurs of interest and assent. But there isn't an ounce of authenticity in the show.

And this is the story of Gore's life: the great care that he has taken—to say things right, to get it right—has once again defeated him.

He is, if anything, more careful now than ever before, after a nightmare year in which he found himself the poster boy for everything that was excessive and seamy and possibly illegal about the Clinton-Gore campaign's fund-raising in the 1996 election. As the calendar flipped toward the new year, it seemed that Gore's ordeal was over: Fred Thompson's Senate investigation had sputtered to a frustrated halt, and Attorney General Janet Reno had decided against the appointment of an independent counsel to probe the president's and vice president's phone calls to donors.

But in the end the controversy raised the question, always a Beltway favorite, of whether Gore has what it takes. He had stumbled so badly in addressing the problem, with his staff's ever changing accounts of the slapstick Buddhist-temple fund-raiser that vacuumed up illegal contributions from monastics, and with his own strange press conference in the wake of the revelation, last March, that he had called donors from the White House. Repeating seven times the assertion that "no controlling legal authority" existed to suggest that an arcane law against such solicitations applied to him, he showed the tone-deafness to nuance that has always seemed so baffling in a man so smart. When it was over, he had done almost enough damage, in under half an hour, to undo four years' worth of golden press.

At a deeper level, the scandal called into question Gore's own most precious beliefs about his career. Gore has always sought to be something subtly different from a real politician: something smarter, more rigorous, less compromised. "Gore has spent so much of his career trying to be an issues guy—trying desperately not to look like the usual politician," says a man who has known him for years through Tennessee politics. Reporters "hold him up to a higher standard," adds Bob Squier, Gore's longtime media adviser. "And the reason is that the standard they feel they're holding him up to is his own."

For any other politician, it would be a normal day's work to assert that he had done only what everyone does, and what the law allows. To see Gore reduced to this argument was to see a man choking on his own most cherished vanities, and to wonder, Why does one of the country's most successful politicians have such a pained contempt for his trade?

It's not that Gore has ever shied away from the hardball aspects of politics. In his ill-fated 1988 race for the presidency, he managed to convey only the coldest, most aggressive parts of his personality, attacking his fellow candidates at an unusually snarling pitch. And he has been rightly described as one of the most calculating politicians at work in America today. From the time he entered Congress in 1977, he carefully picked issues that were susceptible to near-term solution—preferably solutions that could be credited to a single congressman— or those, like technological development, the environment, and nuclear strategy, that appealed to his love of the abstract. "My sense is that he rarely does anything instinctively," says John Seigenthaler, the former publisher of the Nashville Tennessean, who is a close family friend. Even on the issues that most engage Gore, critics say, his rhetoric far outreaches the actions he proposes, which tend to stamp him as—in his words—"a raging moderate."

Certainly he has shown himself capable of the strategic reversal: initially opposed to legal abortion (Gore once even voted for an amendment defining an embryo, from the moment of conception, as a "person"), he later embraced abortion rights. And ever since he ran for president, he has worked assiduously to lessen the hostility spawned in Hollywood by his wife Tipper's mid-80s campaign to alert parents to obscenity in rock lyrics.

Gore has pursued his political ambitions with rare drive and discipline. From the time of his first electoral victory, he followed a bruising schedule of town meetings in his district and, later, his state. As vice president, he has pursued the high-end version of this hunt, jumping with a will into the most punishing travel, the dullest ribbon-cutting. On a Sunday in late October, he returned to Washington in the early hours of the morning from a political dinner in Iowa, got up and ran in the 26.2-mile Marine Corps Marathon with two of his daughters, and in the afternoon stood for two hours in a werewolf costume at his annual Halloween party while members of the press corps that had made his year so miserable filed past to shake his hand and pose for signed photographs with him and Tipper.

Finally, he has always been at or near the top of his class as a political fund-raiser. In both of his Senate races, Gore amassed impressive war chests; he raised $2.6 million for his 1990 campaign, in which his opponent spent less than $9,000.

For this reason, the public-interest community marveled at the tone of the commentary with which the press covered Gore's engulfment in the fundraising controversy. "It [was] more than a little amusing to me that everyone was shocked—shocked!—to find that he was a normal pol," says Charles Lewis, executive director of the Center for Public Integrity. "Anyone who had watched him knew that he was always in the money. He's not this geeky, safety-glasses Eagle Scout guy that is the image we've all constructed for him."

But none of this changes the overriding ly strange truth: politics is not something that Al Gore is innately good at. It's not even something he likes very much—only something he has mastered through will, ambition, and grindingly hard work. "It always strikes me," says a close friend, "that politics is an odd business for Gore to be in."

"I think if Al Gore had not been the son of his father . . . and was not expected to pursue a career in politics, he never would have," says a former Clinton White House official.

Enter the dread comparison: Al Gore is no Bill Clinton. Reporters who just yesterday were deriding Clinton as "slick Willie" for his amazing powers of seduction are today comparing Gore unfavorably with him. But the contrast does point up the fact that Gore is extraordinarily introverted for a world-class politician. "Maybe if [Gore] wasn't so disciplined about it, it would fall apart, because it's not what he does when nobody's looking," says a former Clinton aide. "Clinton doesn't have to be so disciplined, because the drive is so innate. Gore has to lock it in much more carefully."

Gore's characteristic approach to any problem is to take the largest, most systemic view he can. Thus, when he found himself at 23 full of a young man's questions—about what he had seen in Vietnam and what he should do with his life—his answer was to attend a year of divinity school. When he decided, as a young congressman, to get involved in the then feverish debate over nuclear weapons, he immersed himself in a 13-month tutorial about nuclear strategy and emerged from cogitation with his own grand strategic plan. And when his young son nearly died, in 1989, Gore undertook the most bookish midlife crisis it is possible to imagine, studying works of psychoanalysis and pondering the grand societal impact of family dysfunction.

It is hard to conceive of a mind less rooted in the conditional, the transitory, the relative—the imperatives that rule most politicians' lives. This mind, in its struggle to shape itself to a life at odds with its natural contours, is Gore's great gift and Gore's great weakness.

"If Gore had not been the son of his father, expected to pursue a career in politics, he never would have."

Like most reporters who travel with him, I've met the other Gore, talking at the back of the plane about things like kids and books and birthdays. It's a political transaction, to be sure, but Gore's ease in it and his air of self-awareness are real.

That, however, is all off the record. Locked away. Perversely, Gore is far too careful ever to show that side of himself where it could do him the most good. Instead, he begins our one formal interview with a lengthy monologue. And as he gets well into it—CarefulMan has something very specific that he would like to convey—he is so changed from his earlier self that I am gripped by the temptation to do something, or say something, shockingly wrong. To call him a name; to ask him to dance; to peer down his throat, perhaps, and hallo Is anybody in there?

Since becoming vice president, Gore has so insistently spoofed his own rigid quality that he has successfully defined it as a simple personal attribute like any other: like having green eyes, or a bald spot. It comes, then, as something of a shock to watch him in the public arena. He isn't merely a bit more formal, a few degrees more self-conscious. When Gore vanishes behind his public mask, he seems to undergo a wild, almost violent act of self-compression.

The athlete's body language suddenly broadcasts a lack of fluency: his arms dangle lifelessly from his shoulders, and he seems to have no joints at all above the waist. The deliberate pauses in the middle of his sentences stretch into yawning silences. "There is simply no one in the U.S. Senate," he seems to tell the audience at a fund-raiser for California senator Barbara Boxer. Huh? Oh, there's more. "Who fights as hard for what she believes in as Barbara Boxer."

And when he claps! Gore's awkward way of applauding is legend among former aides. He sticks one hand straight out from the elbow, as if serving a pizza, then mechanically moves the other arm—the whole arm, with that strange jointlessness—up and down like a bellows. "A1 Gore clapping is one of the great sights," says a friend. "Here is a man who was always clapped for. He doesn't have the first idea how to do it."

"He's not this geeky, safety-glasses Eagle Scout guy that is the image we've all constructed for him.

When he is at his worst, his audiences don't even get his jokes. At an especially deadly fund-raiser in Los Angeles, upon hearing himself introduced as the greatest vice president in history, he remarks, "Sometimes, when I hear a phrase like 'greatest vice president,' I think, Jumbo shrimp." The audience of almost two dozen wealthy donors misses the oxymoron and simply stares at him, in puzzlement: Why is this sober fellow talking about crustaceans?

He is more fluid some days than others. But even when he comes close to political ease, he undermines himself at every turn. One former Gore aide recalls a 1996 campaign event at which a young man in the audience introduced his mother. "The vice president said, 'That's your mother? She looks like she could be your sister.' And everyone went, 'Awww, what a sweet man.' The crowd was totally with him. So then he said, 'That's a line you often hear, but in this case it really applies.' Like, I would never use a line on someone; I'm just using my superior powers of observation to reach a biological conclusion."

"He never seems engaged in the moment," says a Democratic strategist. "It's as if there's always an essential part of him standing off in the corner watching himself perform . . . making sure he did exactly what he was supposed to do."

Gore aides and fans have numerous explanations for these strange performances. "Having grown up in the public eye has made him really careful in his public presentation," says one highlevel Gore staffer. Roy Neel, a former aide who is one of his most trusted advisers, offers, "He came to politics very young, and he wanted to be taken seriously. So he was doubly cautious, and precise, about how he presented himself."

There is some validity to both of these views. Yet neither really captures the radical quality of Gore's shifts in behavior. One can't watch Gore's transformations without feeling that they are profoundly connected to Gore's emotional makeup—that there is something chosen about them.

Now watch him in California, delivering a speech to a gathering of biotechnology executives. While he warms up with a string of his dry jokes, his true pleasure here is in getting down to business: to the Cartesian origins of the scientific revolution; to the "gestalt effect" of gene mapping; to "structure-based drug design ... the directed synthesis of new compounds . . . computational science . . . the median review time for new molecular entities, or N.M.E.'s."

"Or N.M.E. 's." He knows their lingo, and he wants them to know that he knows it. Gore is engaged by science in a way that far outstrips the claim on him of any human realm. This intellectual, science-oriented side of Gore is clearly something that he has emphasized in building his image. But it is nonetheless real. During a single day of travel, in "casual" conversations with reporters at the back of his plane, he begins with El Nino and global warming and later manages to touch on the human-genome project; the conversion to scientific use of Cold War intelligence technology; the development of energy-efficient cars; and, in an extended, late-night lecture, climatology. As he talks, he is at one moment scrawling a map of the oceans' primary movements on the nearest piece of paper ("Scientists now think it's a continuous loop, like a Mobius strip"), and at another filching an ice cube from a reporter's drink, with his fingers, to illustrate the actions of melting glaciers.

Some people find this impressive, some exasperating. On the one hand, here is Gore's great Univac of a brain in action, showing off his legendary powers of absorption and categorization. At its best, Gore's dedication to the logic of science makes him less inclined to fudge than most politicians. His long investment in the issue of global warming, for example, culminated in his decision to go to December's Kyoto summit on climate change; the treaty that resulted—which is deeply unpopular among factions in both parties, and faces a major battle in the Senate-will be a vulnerability in his campaign for the presidency in 2000.

"You get the feeling Al's the thermostat of the couple, keeping the temperature level.

CONTINUED ON PAGE 166

FOR DETAILS, SEE CREDITS PAGE

CONTINUED FROM PAGE 122

But like all born explainers, Gore trades more in lecture than in conversation. "The son of a bitch thinks he knows everything," says one man who has occasionally advised him.

Yet there is, finally, something moving about Gore's passion for science. It gives him the lit-up quality of anyone who is willing to embrace something he loves— and points up how flat the rest of his world seems in comparison. Watching him at moments like this, knowing that his political ambitions are two generations old, gives special resonance—poignancy, even— to something Bob Squier told me. "We've talked more about my father than we have about his," said the man who may be Gore's most important political adviser. "Because mine was a scientist."

Albert Arnold Gore Jr. was not literally groomed from birth for the presidency; during at least some of A1 Gore's childhood, the father still held that ambition for himself.

Albert Gore Sr., who served in the House for 14 years and in the Senate for 18, was a proud southern liberal at a time when the 1-word was not the worst thing you could call a Democratic politician. Gore is still revered by southern progressives for his early opposition to the Vietnam War, his largely principled record on civil rights, and a tax-the-rich populism that made him a gadfly among the nabobs of the Senate Finance Committee. With his rich oratory and mane of white hair, he was a senior senator out of Frank Capra. But he also had an edge of the country boy: in his early races he played the fiddle to draw crowds to his speeches.

The presidential bug bit Albert Gore in 1956, when he narrowly lost out to his fellow Tennessean Estes Kefauver to become Adlai Stevenson's running mate, and he was often mentioned as a possible candidate for the presidency or the vicepresidency in 1960. But he never ran, and there was something stubborn in him that repeatedly made him sour his own alliances. Jack Robinson Sr., a former aide of Gore's, told a documentary-film maker in 1993, "I'd look up on the board and see a vote that was 97 to 3 and I'd think, One of those [3] is going to be him."

It was a stubbornness that hurt him badly in 1970, when he faced Bill Brock, a challenger handpicked by the Nixon White House in a bitter race still seen by southern liberals as a watershed. Gore was hammered with negative ads portraying him as out of touch with Tennesseans on race, on school prayer, on Vietnam. But he showed a stiff-necked refusal to modernize his approach to politics. He was Albert Gore, and he was their senator, dammit, and that should be enough. In response, Tennessee elected Brock by 43,000 votes.

Father and son both cried the night of the father's loss. And the senator told his faithful, in conceding defeat, "The truth shall rise again."

Many heard that as a reference to the next Albert Gore. Ever since the younger man entered politics, his father has visibly hungered for a Gore presidency. In 1992, when Gore was tapped to be Bill Clinton's running mate, Albert Gore Sr. exulted to The New York Times, "We raised him for it."

As if this paternal legacy were not goad enough to succeed, there was also Gore's mother, Pauline, who is, according to many people who know the Gores, the shrewder, tougher half of the couple. "If Pauline were Al's age today, it would be her running for president," says The Tennessean's current editor, Frank Sutherland. "Pauline Gore may be the smartest politician I know."

"Young A1 is a lot more like his mother than his daddy," says Court TV anchor and managing editor Fred Graham, a family friend. "She has a more subtle and complex mentality than his father." According to someone who knows Gore very well, it was Pauline who conceived the idea that their son might be groomed to be a president. "It was the father's dream, but his mother's vision. His father had it in his heart, but his mother had it in her head."

I ask Gore if it's true that he is more his mother's than his father's child. "Well, I think that's a very perceptive question," he answers, in his affirming-teacher voice. "It tells me that you have done a lot of work. Because most people just stop at: To what extent is this person his father's son? And how does this explain his total being? It's just so formulaic. The other is also formulaic, but it's closer to the truth."

Among other things, the mother taught her son that there were ways the father was not to be emulated, making clear the costs of Albert's showy love of principle. "A1 by nature is more of a pragmatist than his father," Pauline told an interviewer in 1988. "As am I. I tried to persuade Albert [senior] not to butt at a stone wall just for the sheer joy of butting."

The St. Albans School yearbook of 1965 has a line drawing of graduating senior A1 Gore standing on a pedestal; under his photograph runs a quotation from Anatole France: "People who have no weaknesses are terrible."

"Gore is taken seriously because he's seen as the presidents partner. The minute he's seen as another candidate, he gives up that status."

"He was a stuffed shirt, even then; he was not a kid," says a schoolmate who played on the football team that Gore captained. "He would try to be inspirational, and we would all roll our eyes." Classmates sometimes referred to him as Ozymandias, after the arrogant ruler of the Shelley poem, who cried, "Look on my Works, ye Mighty, and despair!" Another schoolmate notes, "That suggested the schoolboy's intuition that this was a gigantic figure in our midst. But that there was something wooden, artificial, unreal, monumental about him."

This quality—Gore's square-jawed, opaque perfection—is described by people from every era of his life, from fourth grade on. Roy Neel says with a shrug, "You're either attracted to him or, if you're a certain kind of person, you're repelled by him."

When A1 was bom, on March 31, 1948, 10 years after his sister, Nancy, his arrival was announced on the front page of The Tennessean. "We had almost despaired of having another child, much less a son," Pauline told an interviewer years later. "So he has kind of always been a miracle to us." By most reports, the family observed an almost perfect division of roles. Nancy was fun-loving, charming, rebellious. A1 was dutiful, sober, and good. "They were opposites," Pauline Gore told the Los Angeles Times in 1988. "As far as Nancy was concerned, rules were made to be broken. But A1 was fairly much a conformist." Pauline has often described her son in this faintly withering light—telling The New York Times, for example, that he had always been "determined to please."

"He didn't really need any discipline— he knew what he was supposed to do, and he did it," says Edd Blair, a childhood friend from Carthage. "All of us, our mothers loved him."

Between them, Albert and Pauline gave their son a thoroughly political upbringing. Here is a jugeared "little Al" in The Saturday Evening Post, at four, riding the Jeep on the farm with father, mother, and sister. Here he is in an Indian headdress at six, in The Knoxville News-Sentinel, in a corny feature about how he talked his father into buying him a bow and arrow. Here he is at 22, in uniform, in a political ad designed to head off the loss that looms before the senior Gore in his final campaign. "Son," the father tells his boy, "always love your country."

Home was two places—the farm in Middle Tennessee where the Gores raised cattle and grew tobacco, and Apartment 809 in the Fairfax Hotel, on Embassy Row. On the farm, where he spent his summers and school breaks, his father insisted that he work as hard as the hired labor to earn his pocket money. But in Washington there were different lessons to learn. There he absorbed conversations with Clark Clifford, William Fulbright, Sam Rayburn. At 14, he was allowed to listen in while President Kennedy sought the senior Gore's help in pressuring the steel industry to roll back a price increase.

"To ask how he regarded his father's career connotes distance, where there was none," notes Frank Sutherland. "A1 was in it, he was part of it." And when his father lost his Final election, "the senator didn't lose that election, the family did."

Indeed, when the vice president discusses his father's campaigns, a curious thing happens. He is telling the story of his father's first Senate race, in which his opponent—the powerful but doddering chairman of the Senate Appropriations Committee, Kenneth McKellar—posted billboards all over Tennessee saying, THINKING FELLER/VOTE FOR MCKELLAR. "And my mother said, 'Here's what we're going to do. . . . Everywhere there's a sign, put another one right underneath it,' which we did: 'THINK SOME MORE/VOTE FOR GORE.'"

We did. Gore, at that time, was four years old.

He learned from the start to serve two constituencies, silently containing whatever tension this stirred in him. When he was at St. Albans, he rarely spoke of what he did when he vanished, the day after term's end, to Tennessee. And in Carthage, "when he was around us, he never did mention his life in Washington," says Gordon Thompson, the son of the couple who managed the Gores' farm. "He brought himself down on our level. Because he knew, to get along with us, he had to."

Gore's parents sometimes left him with the Thompsons for long periods; when he was in second grade, he lived with them from Christmas until the end of the school year, sharing a bed with Gordon. They were the First of a series of surrogates from whom he drew a needed warmth.

While Gore has been lampooned as "Prince Albert," product of a silver-spoon childhood, the reality was more complicated. Both his parents had come of age in the Depression-ridden rural South: his mother, in West Tennessee, where her father's general store went bust in the Depression; his father, in the hills of Middle Tennessee, where, although his family owned land, he had to work his way through college, stopping and starting while he earned his tuition. Albert and Pauline met when he was attending night law school at the Nashville Y.M.C.A. and she was waiting on tables to pay her way through Vanderbilt law school, where she would become one of the first women graduates. "These are people who had really raised themselves up out of very simple origins," notes David Halberstam, who was an apprentice journalist in Tennessee in the late 50s and knew the family well.

The couple's economic circumstances gradually improved—Albert would become rich after he left the Senate, in the employ of industrialist Armand Hammer. But the senior Gores' correspondence is full of suggestions that, when A1 was young, the family's upper-middle-class existence was a stretch. "I may be the poorest senator up here," Albert Gore wrote in a letter to a supporter shortly after his first Senate victory, and Pauline wrote to a friend that there was no way the family could afford a new car. She shopped zealously for bargain antiques and carefully noted the stock number of some shoes she tried on at Bergdorf's so that she might find a way to get them wholesale. Although the Fairfax Hotel later became the Ritz-Carlton, it was not a posh place at the time Gore was growing up; in any case, the apartment was in their reach only because the hotel was owned by a cousin.

It was nothing like a life of poverty, but it explains why his parents' hopes for him were something more ardent than the casual aspirations of the privileged, who can assume the success of their children. A sense of life's difficulty—of the narrow margins by which families rise and fall—was a part of the family's bedrock culture, and childhood marked A1 Gore permanently with a sense that mistakes are unaffordable.

By the time Gore was admitted to Harvard on a scholarship, his lessons were complete. John Tyson, an economicdevelopment entrepreneur in Washington, remembers meeting the future vice president when Gore knocked on his door in a freshman dorm in Harvard Yard and introduced himself as a candidate for a seat on the freshman council—a post to which a roommate of Tyson's also aspired. "A1 had a big smile and good handshake, and looked you square in the eye," recalls Tyson. "My roommate at that time said, 'Well, it's not fair. He's a professional already.'"

But something happened on his way to the forum. The 60s happened, turning Harvard upside down and sending Gore to Vietnam, as a military journalist, after an anguished decision to enlist that combined his father's political interest with his own guilt at the thought of evading the draft in a pool as small as Carthage. And he absorbed some of his father's bitterness about the older man's defeat.

So instead of jumping right into politics after returning from Vietnam, Gore took a job at The Tennessean—on the condition that he not be assigned to cover politics. Instead he plunged happily into covering hillbilly festivals and burger-eating contests, writing obits and police stories. He was married by now, to Mary Elizabeth "Tipper" Aitcheson, the girl he had met at a dance in high school; they had their first daughter in 1973.

He was, by all accounts, a talented and hard-driving reporter. "He had an intense pride of authorship," says Roy Neel, who was at the time a sportswriter at a rival paper. "If he was going to be associated with something, if it was going to have his name on it, it better be damned near perfect." Gradually Gore found himself lured—like any other young reporter drawn by ambition to the prestige stories—onto the government beat. His work led to the indictment of one Metro Council member for soliciting a bribe, and he covered the arrest and indictment of a second council member on a similar charge.

Some of those around Gore believed his protestations that he had lost interest in politics. But at the back of the newsroom, the more hard-bitten reporters on staff knew a racehorse when they saw one, even in a pasture full of mules. "When we didn't have enough to do, we would plot Al's political future for him," says Frank Sutherland. "When we really didn't have enough to do, we'd Figure out his path to the presidency. He'd go, 'Oh God, don't do that.' "

Even as he fought it, the training of a lifetime was gradually working its way to the surface. Gore enrolled in law school in 1974. And in 1976, when the congressman who held his father's old seat in the House retired, Gore decided in the space of an instant to plunge back into politics.

"On, like, Friday afternoon A1 was—his hair was a little bit long, and he was working away as a reporter," says Doug Hall, who was a colleague at The Tennessean and, much later, a Gore adviser. "At that point, I don't think he owned a suit. But on Monday morning he had a navy-blue suit and a haircut, and was announcing for Congress."

This story, of his cleansing detour through the newspaper business, was the story that CarefulMan was bent on telling at the start of our interview. And he told it at length, speaking for eight minutes straight: "The point of all that," he concluded, "is that the easy story to write about someone who grows up in a political family who then goes into politics is, well, this person formed an intent, a plan, in childhood, and traveled down this path in rote fashion. The more complicated truth in my case is that those seeds were planted when I was young, but I rejected it. And then, after many years, came back to it on my own terms."

He won a close race in the primary, in which he forbade his father to make appearances but benefited greatly from the family's old contacts and donors. ("I don't think he would have won without those resources," says Roy Neel. "But after that it was all him.") It was the last tight race he would ever have in Tennessee: he won the general election handily, as well as his next three House bids and two Senate elections, in 1984 and 1990.

From the start, he cut a different figure in politics: more studious, more intellectual than his congressional brethren, trailing in his wake a whiff of aloofness or—some thought—contempt. "He doesn't know as many members, or have the personal relationships that you would expect for someone who had spent that time up there," says Gore's friend Debbie Dingell, a General Motors executive who is married to Representative John Dingell.

It would remain striking, throughout his career, how much he continued to define himself by those five years he worked in journalism—describing politics as "an extension of being a journalist." His specialty, in the House, was the oversight hearing, in which he would expose some malfeasance in need of punishment or regulation—in the pharmaceutical industry, among makers of baby formula, by the dumpers of toxic waste. "It's just like being a reporter," he told friends, "only you've got subpoena power."

He had found a way to meet his duty while calling it something else.

Twenty years later his pleasure at his early career in journalism is still palpable. Sutherland, now a close friend, introduced him as the keynote speaker at the April 1996 luncheon of the American Society of Newspaper Editors. With a rare lightness of touch, Gore treated the gathered barons of journalism to his reminiscences of being a wet-behind-the-ears reporter who fell for the oldest hazing trick in the book: one day he got a call about the death of one Trebla Erog, a Swedish gynecologist. Failing to recognize his own name, spelled backward, he conscientiously wrote up Erog's obituary, right down to his membership in the Knights of Columbus.

Gore's tale, and his self-deflating manner of telling it, had the editors in stitches. Then suddenly he turned on a dime and began his formal address on the subject of "reinventing government." His voice slowed; his face lost its mobility; the assembled listeners fell into the attentive stupor of children in the last hour of the school day. Seeing Gore so assiduously separate these two pieces of his world was like watching someone holding at arm's length two potent chemicals, each benign on its own but liable to explode if brought into contact with the other.

"The focus on Gore flowed from a simple fact: he had made many more one-on-one appeals to donors than Clinton had."

Friends swear that under his throttled, somewhat wintry mien, Gore is an emotional man. His family life provides plenty of evidence that this is true: his marriage to Tipper is almost universally regarded in Washington as the rare political marriage that has retained some fire after 27 years. "Gore and Tipper really are like teenagers in love—a lot of handholding, a lot of touching," says a friend. And he has lived out a real commitment to his four children—Karenna, 24, Kristin, 20, Sarah, 19, and Albert III, 15. Only the youngest remains at home (the three girls all chose to follow their father to Harvard, and Karenna is now a law student at Columbia), but for much of his vice-presidency, Gore blocked out great holes in his schedule—for field-hockey, football, and lacrosse games, back-toschool nights and sports banquets—that were genuinely off-limits to all the other claimants on his time.

The Gores have worked hard to maintain a zone of privacy, even within the formality of the vice president's mansion. They go to movies—quietly, slipping into theaters at the last minute to take up seats reserved by the Secret Service—and give informal dinners for friends. They have kept the two houses they own elsewhere, which speak volumes about their traditionalism. One is the Arlington, Virginia, Tudor house (worth more than $500,000 today) that Tipper grew up in. The other is their modest farm in Carthage, where the family spends vacation time. It faces Al's parents' house across the narrow Caney Fork River.

Yet Gore's efforts to show his emotional side, through speeches about such personal tragedies as his sister's 1984 death from lung cancer, have evoked mostly cynicism in his listeners. He is strangely full of false notes at times like those, deaf to the effects he has on others. In a recent chat with Time magazine, for example, he suggested that Erich Segal had based the romance depicted in Love Story on A1 and Tipper Gore. The claim promptly touched off the kind of pointless minor controversy that is fast becoming Gore's signature. For Segal denied it, saying that any small resemblance between Gore and the novel's Oliver Barrett IV had to do with their struggles to escape the career expectations of their domineering fathers. In any case, the boast was vintage Gore: the least hip testimonial one can imagine to a passionate love life.

And his familiar emotional role—A1 the dutiful, the even-tempered, the man without weaknesses—is still with him. Hearing people describe A1 and Tipper together, one can't help being reminded of A1 and his sister. "Tipper is the more emotional of the pair, the more sensitive to feelings," says Frank Sutherland. Her job is watering the family's relationships with others, reminding him of the human side of life.

In turn, Gore's job is to be the steady one. Tipper is seen by friends and associates as far more volatile than her husband—up and happy one day, withdrawn the next. "Tipper is really a very complicated piece of machinery," says a good friend, who perceives an element of solicitude in Gore's attentiveness to his wife. "It's as if there's an unpredictable quality only Al knows, in Tipper. You get the feeling he's the thermostat of the couple, keeping the temperature level."

In becoming Clinton's vice president, Gore joined another partnership that defines him as a steadying force. Political associates repeatedly described to me the vice president's ability to lance Clinton's legendary temper. White House press secretary Mike McCurry says he never allows the scheduling of a presidential press conference until he knows that Gore will be in town for the "pre-brief," in which aides help the president anticipate questions—and allow him to vent his exasperation in advance. "Clinton just spews this stuff out, and Gore says, 'Yeah, that's what they want to see—they want to see those veins popping out on the side of your neck. Your advisers will all tell you you can't do that, but they're just a bunch of wimps. So just go ahead and say that.'"

In exchange, Clinton has tried to convey to Gore some of his own ease at politics. "The president will encourage the vice president to open himself up a little more in public," says a Gore adviser. "He will say, in a meeting, 'You're being a little too abstract here, Al.'"

Just once, Gore cast off the tight emotional camouflage he has worn since his youth. In 1989, at age 41, he was still assimilating the failure of his presidential run when his six-year-old son dashed out of his grasp one day and was struck by a car. Albert nearly died, and it took extensive surgery and physical therapy to restore him to health. The event was a violent dividing line in Gore's life, loosing a lifetime of emotional repression. Gore launched "an intensive search for truths about myself and my life," as he wrote in the book he started a year later, Earth in the Balance—a search that entailed questioning his entire political education. Frierids believe he was encouraged by his wife, who has a master's degree in psychology and has recently made mental health her chief public cause. In the course of Albert's treatment, the Gores participated in family-therapy sessions.

What Gore found was his missing childhood. With the help of a psychology professor at the University of Tennessee, he explored the whole theme of family dysfunction, becoming fascinated by the Swiss psychoanalyst Alice Miller's The Drama of the Gifted Child, a classic summary of the ways in which parents inflict their unfulfilled dreams and narcissistic needs on their children. A 1993 article by Katherine Boo in The Washington Post Magazine reported his deep interest in the book, the way he urged it on friends. And it is easy to see why. The personality type laid out in Miller's slim book, as she describes the children of such parents, might be a road map to the psyche of Al Gore: there is the will to achieve as a way of earning love; the development of the intellect over the emotions; the severe repression of the true self. The child, Miller wrote, "develops in such a way that he reveals only what is expected of him, and fuses so completely with what he reveals that—until he comes to analysis—one could scarcely have guessed how much more there is to him."

In Earth in the Balance, Gore hints at the passionate new connections that had been made in his mind. In a chapter titled "Dysfunctional Civilization," he spins out, for 11 pages, a lesson on dysfunctional families as a metaphor for civilization's abuse of the earth, using the fervent overstatement of one writing in a new voice. "And because [the developing child] doubts his worth and authenticity," Gore writes, "he begins controlling his inner experience—smothering spontaneity, masking emotion, diverting creativity into robotic routine, and distracting an awareness of all he is missing with an unconvincing replica of what he might have been."

The chapter is fascinating in how vividly it shows his burdens. It is, in miniature, the story told by the entire book, a dense 408 pages that range over biology, theology, geology, psychology, and history, among other disciplines: that it wasn't enough for Al Gore to save his son, or to save himself. These impulses must all be in service of something larger—a drive that is at once self-negating and grandiose. There is the operatic tendency to see the world as a reflection of his own struggle and the solipsistic certainty that a big change in his own life (his response to Albert's brush with death) might reasonably pave the way for a change in the life of the world. "It is that experience of personal healing, in turn, which made it possible for me to write this book and which convinced me that the healing of the global environment depends initially upon our ability to grieve for the deep tragedy that our collision with the earth's ecological system is causing."

There has never been a clearer expression of how importantly, with what a sense of assigned burden, Gore goes about living his life. Yet Gore's hunger to understand himself is also one of the most attractive things about him—and a true rarity in a political culture that fears nothing more than sincerity. There is no telling where that impulse might have taken him, if allowed to flower. As it was, this passage in his life taught him to spend more time with his family; it led him to pass up the 1992 race for the presidency; it made him resolve to ditch some of the caution that had rendered his 1988 candidacy so full of position papers but empty of conviction.

And then Bill Clinton called to offer him the vice-presidency—called him back to the realm of performance and duty. That other Gore slipped again behind the mask.

The life of the vice president mirrors, uncannily, the life of the dutiful son in a political family. The vice president is shipped around the country like a package, handed from city to city by ever shifting groups of agents and advance people and local volunteers: more pictures to be snapped, more hands to be shaken. To a man with Gore's background, it must be as uncomfortable as the most painful history can be, and as comfortable as home. He can live there forever, as long as he doesn't have to give himself—his real selfover to its demands.

So that is what Al Gore is up to when he vanishes behind his mask: he is hiding in plain sight.

The Gore who remains before our eyes —that proper, sober, who-me? figure who stood at the center of the campaignfinance scandals—is left to contend with an enormous irony. His discomfiture with politics was widely seen as the reason it was so hard for him to deal with the political chaos he had suddenly created. Less closely examined was how it got him into the mess in the first place.

How was it that Gore, with his long record of caution, suffered so much more damage than Clinton in the finance scandals? By last fall, Gore's poll numbers had plummeted, while Clinton sailed undamaged through the storm. In one September poll, only 34 percent of Americans had a "favorable impression" of the vice president, whereas 59 percent felt positively about the president. Part of the reason, to be sure, was political sport: there was far less fun for reporters and Republicans in rooting out fund-raising violations by a man who had already run his last race. And the coverage of Gore got its traction in part from a widespread sense that it would be bigger news (or a deeper hypocrisy) if the squeaky-clean Gore had cut some ethical corners.

But the focus on Gore also flowed from a simple fact: he had made many more one-on-one appeals to donors than Clinton had. In sum, Gore followed Clinton's lead in promising to call potential donors, but Clinton ducked, neglecting to make most of his calls, while Gore duly embarked on some 45 calls.

Never, according to Gore's closest aides, did Gore sit down and systematically examine the underlying question of whether it was a good idea for the president or vice president to make such calls, from the White House or anywhere else. Because while Gore cares a great deal about probity, there is something even more deeply ingrained, something that matters just a little bit more: meeting the test; bearing the burden; doing his duty. In a time period bracketed by the Democrats' disastrous losses in the fall of 1994 and the presidential election of 1996, a crisis mentality gripped the Clinton White House. They were desperate to raise money for a massive series of ads before the fall campaign. And it was simply in Gore's nature to salute and start marching.

If Gore ever once let up at this—if he Lever exempted himself, or let himself slack off on the distasteful parts, the way Clinton sometimes does—it might threaten the whole structure of his vaunted discipline. To Gore, most of politics is eating spinach; how was he to notice if all those phone calls left a bad taste in his mouth? Perhaps the most revealing thing he said at his strange press conference, about halfway through, was "I felt like I was doing the right thing."

This is why the fund-raising scandal, even if Gore has successfully put it in the past, hints at the central question that will dog his candidacy and, if he succeeds at that, his presidency. He knows the difference between right and wrong, but does he know the difference between right and duty?

It's an open question, even according to some of his admirers, who see in Gore a basic decency, a concern with right outcomes that far outshines Clinton's. "I don't know . . . whether the [Boy Scout] kind of thing in him would make him say, 'This far and no farther.' Or whether the kind of literal side to him that says, 'Well, the rule book says you have to make these compromises,' whether that would get him to just deal things away," says one former colleague from the Clinton White House. "Would he go, 'You know what? Forget it—I can't do that.' Or would he go, 'That's the way the game is played'?"

For now, Gore's greatest political strength continues to be the vicepresidency. "He's taken seriously because he's seen as the president's partner," notes Mike McCurry. "The minute he's seen as another Democratic candidate out there grubbing for delegates, he gives up that status." Gore continues in high favor with Clinton, who fully understands the tricky calculus that faces a vice president running as a "New Democrat" against a likely opponent such as Representative Dick Gephardt, who has already staked out the issues that most appeal to the more traditional segments of the party, which dominate the nomination process. On trade issues, for example—where Clinton's freetrade policies are anathema to the unions— Clinton and Gore have agreed that Gore should take a lower profile now than he has in the past.

But there are disadvantages to being the front-runner so far in advance of the campaign. For at least another year Gore will remain the biggest political story in the country, facing a Washington press corps starved for significance. And Gore's stock is still very low among the herdborne beasts who make national opinion. His virtues are not virtues they care for very much, and his weaknesses are of the kind they can smell from 10 miles off.

And this is a recipe—high stakes, huge publicity, plenty of time to think a thing to death—that plays to Gore's worst tendencies. Will he spend this time shedding the cautions that constrain him? In order to do that, he would have to trust himself, innately; he would have to believe in his instincts—in the still, small voice that could have told any other politician in America that "no controlling legal authority" was a mouthful of weasel words. He would have to touch the stuff of voters' lives, and be touched by them in turn.

Or will he double and triple his guard, and circle back and double it again? As he boards Air Force Two for another leg of his journey, it is hard to believe that the habits of a lifetime can be changed. He springs up the last step of the airplane stairs, landing in a jaunty little pirouette that brings his wing tips smartly together and his body to attention, facing out. Head held high, he raises one hand aloft in the standard, statesmanly wave goodbye: right, to the phalanx of highway patrolmen who have helped with his motorcade; straight ahead, to the little clot of ground crew and volunteers that awaits his departure; left, to the empty tarmac.

He waves with equal warmth in every direction, whether or not there is anyone waving back.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now