Sign In to Your Account

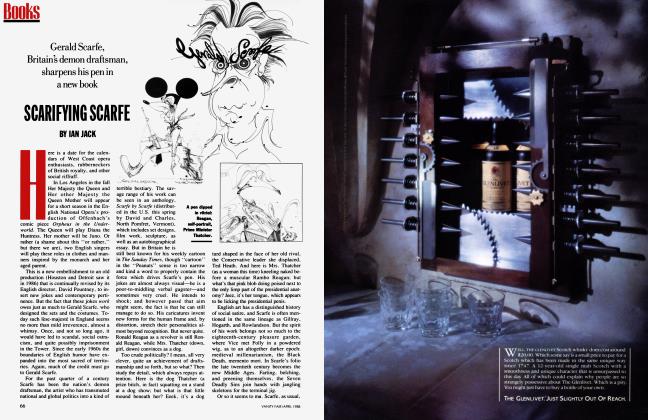

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowWhat Lulu Wanted

The Runaway

In 1928, screen siren Louise Brooks walked out on Paramount to star in two daringly sensual films in Berlin. They made her a movie legend, but ended her Hollywood career. Eight years before her death in 1985, she held forth on sex, the studios, and close friends Buster Keaton and Charlie Chaplin

TOM DARDIS

In 1977, as I was beginning a biography of Buster Keaton, the British film historian Kevin Brownlow told me that I should speak to Louise Brooks. Louise, he said, was certain to tell me all about Buster’s relations with women and might give me an insider’s view of the reasons for his decline into obscurity. One of her Hollywood lovers had been William “Buster” Collier Jr., a now forgotten leading man who in the 20s was one of Keaton’s best male friends. Brownlow was convinced that Louise could recall for me better than anyone what Keaton was like in the days of his great fame.

Brownlow had visited Brooks in her tiny apartment in Rochester, New York, where she led a secluded life enlivened by writing extraordinary articles for esoteric film journals, which were collected in 1982 as Lulu in Hollywood. The articles revealed a unique sensibility and intimate knowledge of Hollywood and Berlin in the last days of the silents.

The girl with the sleek black hair cut in bangs and the bewitching look of false innocence epitomized the Jazz Age and the new sexual freedom of the 1920s. As a 19-year-old Ziegfeld Follies dancer, Brooks signed a Paramount contract that led her to Hollywood, where she would come to count Keaton, W. C. Fields, John Gilbert, and Clara Bow among her friends. In 1928 she dared the lightning by walking out on her contract to make two films in Berlin (Pandora’s Box and The Diary of a Lost Girl) with the great German director G. W. Pabst. A heavily censored Pandora’s Box ran only briefly in American theaters—and The Diary of a Lost Girl not at all—but Brooks’s performances became legendary. Her defiance of the Hollywood system effectively destroyed her career in America. When she began publishing film studies in the 1950s and 60s and granting interviews to writers such as Kenneth Tynan and Christopher Isherwood, she became an icon. Brooks’s piercing intelligence, combined with a savage wit, brought the 20s to life and stirred interest in the two remarkable silent films she had made with Pabst, which are now widely shown. She became a “star,” in fact, 30 years after making her final film.

CONTINUED ON PAGE 183

"The whole history of the big studios is a graveyard of stars who got out of control."

CONTINUED FROM PAGE 174

Following a few tentative phone calls, Louise Brooks and I began a correspondence that continued for two years. What started slowly became a steady stream of letters from her, as many as two or three in a week, some running on for six pages or more, all written, she claimed, to ensure that I “would get it right” and not produce another of those hateful Hollywood bios by people who know nothing of the era.

She began with the problem of language, of how people really talked in the 20s, finding that most contemporary writers were guilty of distortion:

I beg you not to pad your book . . . with invented dialogue made “real authentic” by “fucks” and “shits.” ... I tell you truthfully this has been invented by the Hemingway he-men such as [the director] Billy Wellman—and writers who fill empty pages with the stuff. Up to 1940 when I left Hollywood no man swore before women, and [Carole] Lombard was the only woman who got away with it. I never swore before 1943—disgusting habit—ugly, meaningless—God damn it.

Early on in our correspondence Louise warned me of the dangers involved in speculating about a subject dear to most modern biographers:

In an effort to solve a non-existent mystery I hope you don’t mess with Buster’s sex life—this is what my darling Sam Johnson said in Lives of the Poets—about “Men who cannot bear to think themselves ignorant of that which, at last, neither diligence nor sagacity can discover.”

Within a few months, however, she became far more frank and personal:

I cannot resist MY subject, SEX, and pouring out my wisdom although I know no one can know of others’ sexual pleasures—and pains, not even of those we go to bed with— another partner, another performance. Indeed I do not even know my own, for I have rid myself of a good lay as fast as a bad one.

But last year, as I itemize everything, I made a rough count of how many men I’ve been to bed with. At a modest 10 a year from 17 to 60 it would come to 430. Therefore I feel competent to make some guesses about Keaton. (What a pity I did not know you were going to write a book—I would have researched him. 431.)

Buster was very sexy, very relaxed and easy with women—the first sign of a man secure in his performance. I think he was capable of love but like me he was possessed rather than choosing to possess. (I married [film director] Eddie Sutherland who bored me in bed, and [Chicago socialite] Deering Davis who was repulsive to me.) . . . Sex never influenced the decisions that shaped Keaton’s life.

In addition to supplying me with her impressions of Keaton’s sexuality, Louise offered contrasting testimony about Charlie Chaplin, with whom she had spent most of the summer of 1925 in New York. Chaplin was in town for the opening of The Gold Rush. He was glad to be away from California, where his marriage to Lita Grey had become oppressive. He was worried, however, that he was being shadowed by employees of newspaper tycoon William Randolph Hearst, who believed that Chaplin had had an affair with Hearst’s mistress, Marion Davies.

We would begin an evening (1925) in his suite at the Ambassador [Hotel] in New York—he would give a series of hilarious imitations for me, Peggy Fears, A. C. Blumenthal, Jack Pickford and Winfield Sheehan [all celebrities at the time—showgirl, financier, Mary Pickford’s brother, and the production head of Fox Films]. Then Jack and Winnie would leave and Charlie would become the hunted man, seeking Blumie’s advice about the detectives he felt sure Mr. Hearst had on his trail. . . .

Then Blumie and Peggy would leave and Charlie would go into his seduction scene with me. He had his sexes mixed up. Instead of playing the lazy, watchful tom cat (like Keaton) he rolled and slithered and rubbed like the lady cat. This was a technique suitable only for innocent little girls. (Men’s choice of women is always determined by the success of their particular love-play.) [Silent-film actress Pola] Negri wanted publicity, Davies wanted fun—[actress] Peggy Joyce and [Chaplin’s third wife, Paulette] Goddard were whoring for stardom.

Brooks then noted Charles Dickens’s passion for young girls.

In 1836 when Dickens married Kate Hogarth (20) he brought sister Mary (16), whom he really loved, to live with them. When Mary died in 1837 he nearly lost his mind. Upon reading The Old Curiosity Shop 1840-41, old lady Hogarth [Kate and Mary’s mother] made him laugh when she said he didn’t fool her—he was Quilp and Mary was Little Nell. (Nabokov used this allusion [Quilty] in Lolita.) . . .

“Up to 1940noman swore before women, and Carole Lombard was the only woman who got away with it.”

I am peculiarly interested in this subject because I was “molested” at 9 by Mr. Flowers in Cherryvale [her hometown in Kansas], and, although this perversion is as common today as it was when Ruskin and Lewis Carroll were on the prowl, the lips of the victims and their mothers are sealed. We alone would have made Lolita a best seller in spite of the fact that Nabokov, the dirty rat, made Lolita the seducer.

Louise had much to say about drinking—her own and that of many of her friends in Hollywood.

I never appreciated how lucky I was to have been able to get drunk with the cleverest minds in the world (even if I never heard Bob Benchley say anything funny). ... I assumed that everyone got drunk as I did and fell apart after 4 drinks. Fitzgerald was an example of that—“You can’t write on gin.” But . . . booze was the magic potion that opened the door to [Faulkner’s] secret world. . . . Proust too wrote on massive doses of drugs. Genius apparently possesses a power of control and management of drugs unknown to doctors and psychiatrists. Keaton lost this power when he was driven out of his “unique world” and caged in the MGM Zoo.

I soon noticed that Louise needed no urging to discuss literature. Indeed, she often preferred it to film talk. Too many of her visitors, she complained, were simply “movie nuts,” who thought of not much else. She told me that William Randolph Hearst had caught her stretched out on one of his huge billiard tables at San Simeon, reading Aldous Huxley’s 1923 novel, Antic Hay.

She was sensitive about being identified as someone who read difficult books. She recalled an incident in 1958 when she encountered the German film critic Lotte Eisner in Paris, where Brooks was given a month of hommage at the Cinematheque Frangaise. Eisner liked to introduce Brooks by citing her reading tastes.

And inevitably she would say, “Louise reads Proust,” exhibiting me as the prize dunce beautiful actress in the manner of a pony counting to ten with a hoof beat. . . . One night Lotti [s/c] and I went to Man Ray’s where he was entertaining a strange couple who had come to look at his paintings. Sure enough Lotti said, “Louise reads Proust,” and I was inspired to re-enact Keaton’s comedy strangling scene [in which Keaton places his hands on the throat of his beloved after he sees her rejecting some of the scarce firewood in favor of more aesthetically pleasing twigs for his engine in The General]. “God damn you, Lotti, if you say that again I’ll kill you,” I said, grabbing her by the throat, shaking her lightly, then letting go with a laugh. However, I failed to express Keaton’s corrective sweetness. Lotti was frightened and the strangers left thinking I should be locked up.

Louise was a woman of intense, even violent feelings about the people she met in New York and Hollywood. In her letters she heaped withering scorn on her favorite targets—Marlene Dietrich, the writer Anita Loos, and Joseph Schenck, who produced all of Keaton’s silent films.

[Schenck] was generous with money and mink coats. . . . He must have been all powerful in negotiating Fox contracts. One night at Arrowhead Springs (1939?) I watched him dance the rumba (and damned good) for 2 hours with [Sonja] Henie who would not have wasted a single wiggle of her ass on a man who didn’t spell money.

When I argued with Brooks about some of her objects of loathing, feeling that she must be overstating her case, she replied:

Yes, I am a violent woman. I had counted on old age, loss of energy, and arthritis to cool me out. . . . What makes the midget giant ego Loos so poisonous is that all film fans believe her—“she was there.” Her poison extends to endless talk shows and interviews. Moving farther and farther from fact and truth towards soap opera.

Brooks was particularly incensed by the tendency of some of Hollywood’s oldtimers to “recall” events that never occurred. She thought that Loos and director Howard Hawks had begun to believe their own stories:

They lie, invent, glorify themselves. Kevin [Brownlow] told me that Howard Hawks actually told him [that] / dived 75 feet into a tank of water in A Girl in Every Port.

It may well be that after nearly half a century Hawks genuinely believed he’d seen Louise obey his command to take that dive.

Last year I made a rough count of how many men I’ve been to bed with. At a modest 10 a year, it would come to 430.”

I soon had trouble keeping up my side of the correspondence and decided that it was time to pay a visit to Rochester, where in March 1977 I found an often bedridden recluse who was as voluble in the flesh as on paper. She was suffering from an arthritic hip condition and the effects of steadily worsening emphysema. Her pain was often extreme, but it did not interfere with her incessant letter writing, telephoning, and reading. She did all her own cooking, and that first day she prepared a wonderful egg dish. When I later complimented her on the omelette, her reply was characteristic. I hadn’t gotten it right! The dish she had served that day, she informed me, was scrambled eggs, most certainly not an omelette.

Louise was stoic about her exile in upstate New York. She had gone there in 1956, after what she described as “various methods of self-destruction,” beginning with her walking out on her Paramount contract. The Hollywood of the 1930s had taken its revenge by offering her a series of bit parts in undistinguished films—a stark contrast to her earlier, starring roles. Rochester, however, was at least the home of the George Eastman collection of old films, a sort of American cinematheque, which her champion and lover James Card had assembled. It was at Eastman House that she began her film research on Lillian Gish, G. W. Pabst, Greta Garbo, and Humphrey Bogart, and the writing of her essays, which were published in Positif, Sight and Sound, and Film Culture. These brought visitors to her from all over the world: My last visitor was Christopher Isherwood on a friendly call combined with filmwatching at Eastman House. ... I hope you get more nourishing stuff out of me on Keaton and Schenck than I got out of Ish-Ish on Auden and Vidal.

Louise once greeted me at the door with “How dare you say that Joe Schenck had an ounce of human kindness in his vile body?” Louise had no mercy for Schenck or, for that matter, any of the Hollywood producers of the 20s, asserting that, collectively, they had smashed the careers of many of the leading silent stars, including Keaton and John Gilbert. When I questioned the logic of some of her specific claims, she approached the problem from other perspectives.

Why do you try to set me up against the film producers? I am on their side. I simply won’t have them rewritten as silly do-gooders. They set the picture business up in a way that gave them absolute control over the stars and star directors— anybody who threatened their power and financial supremacy. . .. The whole history of the big studios is a graveyard of stars who got out of control. And the stars had to be completely'destroyed with bad pictures so that the exhibitors and the public would accept their obliteration and so that no other studios could reconstitute them. [Joe Schenck] started on Keaton with The General—lousy publicity. I was in Hollywood in 1927—nobody heard of it. Talkies coming in. . . . Why don’t these slobs [people like Anita Loos] write the truly tragic fact that talkies killed Keaton? I don’t think that father love, wifely support, complete sobriety, the backing of the Schencks and MGM could have reconciled the public to the shock of Buster’s pure, austere face combined with the growl of an angry giant.

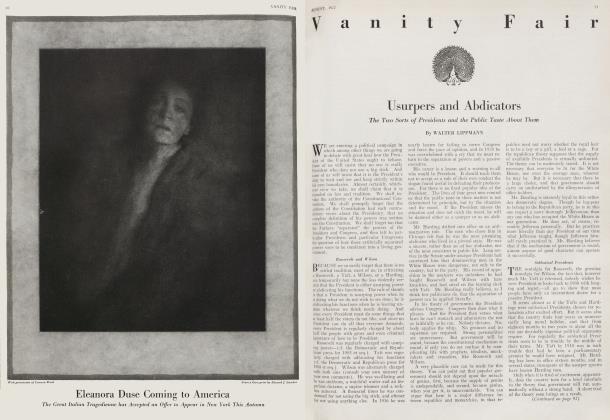

Unlike her famous contemporary Marlene Dietrich (Louise’s rival for the part of Lulu in Pandora’s Box), Louise was not vain about her personal appearance. She once sent me a photograph taken in her apartment in her 70th year, telling me that I was free to use it if I wished, since that was how she really looked.

Rereading Louise’s letters after 20 years has left me with renewed admiration for her passion for truth and what she liked to call “excellence” in art. The truth was the truth, in Louise’s eyes, and absolutely nothing must disguise it. As for art, that needed all the help it could get from people like her, who cared to distinguish between shoddy, counterfeit work and the real, rare thing.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now