Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowDICK SNYDER'S TARNISHED CROWN

Before Dick Snyder was fired as chairman of Simon & Schuster in 1994, he built it into America's largest publisher, and made plenty of enemies. Now, with Snyder's new empire, Golden Books, deep in debt, everyone is wondering how such a talent created such a huge mess

MICHAEL SHNAYERSON

Publishing

His weekend house looks the same as when he bought it 21 years ago, in the midst of his reign at the pinnacle of New York publishing. A 13-room Normandy style chateau with steep slate roofs and mullioned windows, Linden Farm surveys rolling acres to the wooded Ward Pound Ridge Reservation beyond: Westchester as western France. The grounds, though, have changed. Restless at home as at work, Richard Snyder feels compelled to keep improving them. "See those rows?" he says, indicating scores of what look like tiny planted sticks across the front lawn. "Chestnut and walnut trees." They'll take decades to grow to maturity, but that hardly diminishes Snyder's pride at having planted them. "Besides," he says, disarmingly candid, "you know what full-size ones cost?"

Snyder, 66 years old, tramps over to new gardens that he and his wife, Laura, 35 years old, planted for each other, bleak in midwinter but still impressively large. He points out the private playground for their two young boys, Elliott, five, and Coleman, two, and the fields Snyder has cleared amid Linden Farm's 82 acres. But his greatest pride is reserved for the ponds. Three tiered, bass-stocked ponds, connected by trickling waterways. To see them is to gain a first inkling of why Snyder is in the fix he's in today.

In June 1994, Snyder was chairman of Simon & Schuster, America's largest publisher, which he'd built up from modest origins during his long tenure of brilliant book marketing, prescient acquisitions, and harsh, often abusive management. One day that June he was the king, admired and feared, planning to preside for many more years. The next day he was out, deposed, fired by Simon & Schuster's new owner, Sumner Redstone of Viacom, and forced into exile here at Linden Farm. That was when he started in on the ponds: moving earth, hauling rocks, channeling his bitterness and rage and sorrow into backbreaking manual labor, month after month. But thinking all the time: What next?

There had to be a comeback—to work, to win again, to show his corporate assassins how wrong they'd been.

The answer that loomed, peculiarly enough, was Golden Books, known for the little golden-spined classics that since 1942 have been found on the bookshelves of nearly every child in America.

Scuffy the Tugboat, Barbie coloring books, and Mickey Mouse stories might seem a comedown from best-sellers by Larry McMurtry, Bob Woodward, and David McCullough, but Golden was a brand and, after years of lackadaisical stewardship, a bargain.

Or so it seemed.

The ensuing drama has left Wall Street analysts as confused as Snyder's former colleagues and the friends he persuaded to invest in Golden. Somehow, in the three years since he and his backers bought a controlling interest in it, Snyder has managed, as its chairman and C.E.O., to bring a $400 million company to the brink of bankruptcy. At the start of 1998, Golden's stock was trading at about $12 a share on the NASDAQ exchange. Within six months, it was down to 25 cents a share. That's hard to do. Though the stock has perked up a bit on takeover rumors, the news from Golden has gone from bad to worse: defaults on bond payments, angry creditors threatening Chapter 11, and desperate efforts to recapitalize the company's staggering debt.

This month, by coincidence, Snyder's glory days at Simon & Schuster will be limned in a memoir by his old friend Michael Korda, who as the house's editor in chief since 1968 was Snyder's partner in its extraordinary growth. In the justpublished Another Life, a beguiling sequel of sorts to his classic 1979 Charmed Lives, Korda fondly depicts Snyder's fierce ambition and keen marketing instincts. Later this fall comes Isn't She Great, a Universal feature based on a chapter of the new book. It is about Korda's secret and successful effort, at Snyder's behest, to lure Valley of the Dolls author Jacqueline Susann from Random House in the 1960s, and stars Bette Midler as Susann with Snyder portrayed—satirically, perhaps?— by ex-Monty Python trouper John Cleese. But Snyder's current predicament is what fascinates the publishing world. How could this tough, successful businessman—the king!—create such a spectacular mess? Is much of it, perhaps, not his fault? And can he, having tumbled from the mountaintop into this mire, dig his way out before he suffocates?

Snyder has his defenders. "He's a genius, one of the great publishers of the 20th century," declares Penguin Putnam Inc.'s president, Phyllis Grann, who, as Snyder's "mystery editor" in the 1970s, persuaded him to pay $3,000 for a first novel, Where Are the Children?, by a struggling widow named Mary Higgins Clark. "And it would be sad for Vanity Fair to concentrate on Golden Books," Grann continues. Says Tony Schulte, former executive vice president of Random House, "There wasn't another publisher his equal in terms of building a company from the modest, privately owned entity that Simon & Schuster had been into the huge, diversified public company it became." Yet the list of those who still perceive him as the meanest, scariest man in the book world is rather lengthier, and so the curiosity is mixed with a palpable Schadenfreude.

"Dick is someone who simply has to win, even if it costs him more than he could gain."

Is Snyder to blame? The same question might be asked of Charlie Croker, the plagued protagonist of Tom Wolfe's current best-seller, A Man in Full. Like Snyder, Croker is a proud, vigorous C.E.O. in his 60s, married to a far younger woman, accustomed to the spoils of success. Turpmtine plantation is his Linden Farm, personal chefs and jets his corporate style. Like Snyder, he overreaches, sinking millions of borrowed money into a trophy investment just as the market appears to turn. Like Snyder, he's stunned when his creditors grow nasty, more so by the realization that the world as he knows it is in dire danger of falling apart. Is Croker to blame?

Well, mostly—yes.

Part of life is what's there," Snyder muses from his 40th-floor corner office at Golden Books on Seventh Avenue in Manhattan. "And Golden was there."

The office is modest in scale compared with his famous lair at Simon & Schuster, which had Georgian furniture and a private dining room, but it does have a northward, panoramic view of Central Park. Snyder is nattily dressed, in a Hilditch & Key dress shirt set off by sporty suspenders, and seemingly bullish about his plight. If his critics find him nasty, brutish, and short, to borrow Hobbes's own description of life, he has a blustery charm that can be quite winning. And if his vanity is always on display, so, too, is his insecurity. "What I like about Dick," says Christopher Cerf, son of Random House co-founder Bennett Cerf, who has granted Golden a license for his children's-television characters, "is that he's outrageously arrogant yet self-deprecating about it." The swagger is real, but also an act. As is the voice, that unique basso profundo of mangled Boston and mid-Atlantic inflections used for so many decades to cover the original Brooklynese that Snyder can say in all seriousness that it's his own.

"The day after I was fired, Richard Bernstein called me and asked me to come aboard," Snyder explains. Bernstein, a New York businessman, owned a majority share of Golden Books, or what was then called Western Publishing. "I said, 'Good idea, bad timing.' I went into mourning, without even realizing it."

When he emerged, Snyder first tried to buy Simon & Schuster from Viacom, making a blind bid of $3 billion through the venture-capital firm E. M. Warburg, Pincus & Co.; he was turned down flat. So he started meeting with Bernstein, who'd made a killing in commercial real estate and had taken over the then privately owned Western from Mattel for a paltry $5 million of his own money and private financing. Bernstein took the company public and turned a quick stock profit of $100 million, ran it successfully through the 1980s, then lost interest as the share price and earnings sagged. "We had $120 million in debt, if memory serves," Bernstein recalls. "We had $25 or $30 million in cash. We had had a couple of bad years, I'm not denying it." But, he adds, Golden still completely dominated the mass market for children's books.

In his exile, with a small child underfoot, Snyder was spending much of his time reading about education in America. He was fascinated. And here was Golden. A mere children's-book company held little interest for either Snyder or Barry Diller, his longtime friend and willing partner. But what if Golden—the brand—could be extended to create ... a family empire? Not only Golden Books—dusted off and brought up to date—but Golden family videos, Golden theme parks, Golden books on parenting. Now, that would be big.

On May 8, 1996, after more than a year of negotiations with Bernstein, Snyder agreed to buy Western Publishing for $65 million. Most of the money came from Warburg, Pincus, with modest antes from Diller and from Snyder himself.

"If I had to sum up Dick's problem," says Bernstein, "I think he was trying to show up [Viacom's number two] Frank Biondi and Sumner Redstone. He wanted to get even." An old publishing colleague puts it more broadly. "Dick is someone who simply has to win, even if it costs him more than he could gain. He can't be seen—by himself—to lose."

Snyder says he just wanted to work again. His new family weighed on his mind. "I didn't want my children to see their father at home," he says. "And I think there's nothing worse for a marriage than a man being at home and having lunch with his wife every day." Money, to be sure, was another incentive: Snyder negotiated a multimillion-dollar contract that would come to seem excessive as the company tanked.

But Snyder had another, more prosaic reason for buying the company that published Golden Books. Some 40 years earlier, when he was just starting out—before the power and the glory, before anyone thought he was mean—Snyder had worked as a Golden Books salesman. Its founder, Albert Leventhal, had been as close to a mentor as Snyder ever had. Buying Golden would be like coming full circle—like starting all over again.

In fact, Snyder had had no interest in publishing when he got out of the army in 1958. He had assumed that his father, co-proprietor of a men's coat company called Duncan Reed, which championed the natural-shoulder look, would hire him. Instead, his father walked him to the door of his office at 200 Fifth Avenue, gave him $50, and said, "Better a son than a partner." Walking up Fifth Avenue, Snyder ran into a friend who was on his way to a job interview at Doubleday, the book publisher. Snyder went, too, and was hired on the spot.

Unfortunately, the job was in an airless room at Doubleday's Garden City, Long Island, operations. Snyder scrapped his way up to marketing, then heard about an opening at a sales office that served Simon & Schuster, Pocket Books, and Golden Books. The office was in Manhattan; that was enough for Snyder. He moved over in 1960.

"I was very naive," Snyder says, and perhaps he was. An only child, he had grown up in the Midwood section of Flatbush, at that time a solidly middle-class Jewish neighborhood. "It was right out of the old Henry Aldrich radio program or Dobie Gillis," says his oldest friend, Tully Plesser, now a marketing-research consultant. Not for a while did Snyder realize that Doubleday was the Catholic house, in a predominantly Wasp industry, and that both Simon & Schuster and Random House had been started by Jews in the 1920s, in part as a reaction to that. "It wasn't that you couldn't get a job if you were Jewish at the wrong place," Snyder explains, "but you were limited." In his new job, Snyder was recognizing the realities—though the caste system was breaking down. And if he was still naive, he was also ambitious.

"They had an encyclopedia series that was sold in supermarkets," Plesser recalls, "and Dick worked on the promotions. You could get the first volume for 49 cents, then the second for 99 cents, until

you had the whole 15 volumes. It was his first taste of business." Snyder loved it. He would stay up late poring over the numbers, devising new promotions. Soon he won a sales post at Simon & Schuster proper, and began his ferocious rise.

"I want it all!," Snyder told a young Michael Korda, like a character in a Jacqueline Susann novel. "Ambition was plainly there," recalls Richard Kluger, a Simon & Schuster senior editor at the time. "He was out of a rough-hewn background, marginally literate; you never thought he appreciated the writing. That he would pick serious books as his path to glory

"I spent thousands of dollars in therapy coming

to terms with that anger/' says Snyder.

and power—instead of, say, being a tough lawyer—was odd, and sort of endearing."

In an earlier era, Snyder would have been stopped cold for his chutzpah and forced to find a new career. But more than the caste system was changing. The family founders of New York's publishing firms were dying off—Richard Simon had passed away just before Snyder joined the company, Max Schuster was in his decline—and new blood was coming in. Snyder benefited from that without, perhaps, quite realizing why. Later, as one tradition after another fell away, he would have the power— and the pragmatism—to embrace each change, appalling those who yearned for the business to remain a gentlemen's club. In so doing, he would come to personify the changing nature of publishing itself.

At Simon & Schuster, the founders' demise had enabled a talented young editor named Robert Gottlieb to become editor in chief, and by 1968 the books he had brought in, among them Joseph Heller's Catch22 and Chaim Potok's The Chosen, had made the house hot. But Gottlieb nursed dreams of his own to wield control unfettered by publisher Peter Schwed. Holding him back was a doleful Figure named Leon Shimkin, originally the bookkeeper to Dick Simon and Max Schuster, who had managed to secure a majority interest in the company. Shimkin felt Gottlieb was too literary to nurture a broad range of books. And so, one memorable day in 1968, Gottlieb announced that he and two colleagues, Tony Schulte and Nina Bourne, were decamping to take over rival Alfred A. Knopf, the most prestigious name in publishing, at this time already owned by Random House. They left a vacuum that Snyder and Korda made haste to Fill.

Korda simply moved into Gottlieb's office and began acting as editor in chief, though Shimkin refused to grant him the title. Snyder was number two to Schwed, but says he took charge anyway, as much out of indignation as anything else. "The first thing Schwed did was take the entire heritage of Simon & Schuster and sign it over that night," Snyder recalls. "Every writer from Doris Lessing to Robert Crichton, some 50 to 60 books in all. Bob Gottlieb said, 'These authors want to go with me,' and Peter Schwed said, 'Well, that's the way publishing should be.' A lot of my difficulties with the Establishment, and then the press, came because I said 'That's wrong' about things like that." (Retorts Schwed, "I did allow those authors who were particularly attached to Bob Gottlieb to go with him, but they were no more than a handful and not the heritage of Simon & Schuster.") But in Fighting to enforce publishing contracts as legal documents instead of treating tnem as gentlemen's agreements, he won only the makings of a bad reputation.

When Snyder examined Simon & Schuster's backlist—titles that remained profitable year after year— he found little besides Dale Carnegie's perennial best-seller, How to Win Friends and Influence People.

This was a crisis: without some quick moneymakers, Simon & Schuster would be in trouble. "So we took this book we had on toilet training," Snyder recalls, "and we called the author and said, 'How about if we call it Toilet Training in Thirty Minutes'? Could you write it that way?' We thought an hour was too long, and no one would believe 10 minutes. 'Ah, sure,' he said, 'why not?' And that was how we started."

The big break came in 1974, with Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein's All the President's Men. By then, Snyder had replaced Schwed (who no longer had to feel Snyder's "hot breath on the back of my neck") and made Korda's editorship official, cementing a partnership that would last for 30 years without a cross word between them. Each respected the other's strengths; both saw publishing as, above all, a business. Both men were married with children—Snyder and his first wife, Ruth, had a young son, Matthew, and a daughter, Jackie; Korda had a young son—though both marriages were heading for divorce, partly because of the long hours each man was putting in at the office. And both felt, when offered a chance to commission All the President's Men for $50,000, that the price was right. But Snyder was the catalyst. "Dick got behind it at a time when people didn't believe Watergate was true," says Woodward. As a re-

That Snyder picked serious books as his path

to glory-instead of, say, being a lawyer-was endearing."

suit, he says, "I've always put Dick and [Woodward's boss, former Washington Post editor] Ben Bradlee in the same list of characters, who'll say, 'This is what it is, it's the truth, let's go with it.'"

Snyder was the one who decided not to distribute advance galleys of the book to reviewers and booksellers—a radical move that made it front-page news when it appeared. It was followed by other Simon & Schuster best-sellers like Judith Rossner's Looking for Mr. Goodbar and Jane Fonda's Workout Book. Snyder, his instincts

proved, assumed the trappings of corporate success with a gusto that startled his colleagues. "Much as I like Dick, I couldn't help laughing when one day back then we were doing a Today show about publishing," recalls Gottlieb, "and Dick arrived with his publicity person and his car and driver only a few blocks from his office. I thought, Who needs that on the most beautiful day of the year?"

The lifestyle grew grander—Hollywood grand—with the sale in 1975 of Simon & Schuster to Gulf & Western, which owned Paramount Studios. New inheritance taxes and lack of interest on the part of heirs were pushing privately held publishing companies into public hands— another sea change from which Snyder would benefit. To others in the publishing world, Charlie Bluhdorn of Gulf & Western seemed a little Napoleon who shouted himself red in the face and might just be insane. A Viennese refugee who made a fortune at age 21 by cornering the market in malt, Bluhdorn had gone on to acquire a hodgepodge of companies ranging from auto-parts manufacturers to cement producers. None had anything to do with books. But when Shimkin declared his desire to sell Simon & Schuster to Bluhdorn for $11 million—a rosy sum at the time— Snyder saw what the future might be. "The good times are coming," he told Korda. "Trust me."

Bluhdorn Snyder run the company as he wished. He also encouraged corporate perks on a scale even Snyder had never imagined. Soon, along with his chauffeured town car, Snyder had a private chef, Felipe, and shuttled back and forth between New York and the West Coast on Gulf & Western's corporate jet. "He would have been very out of fashion today," Snyder says of Bluhdorn. "He would say, 'I don't want you to get your groceries or hail a cab. I just want you to concentrate on working—that's a good investment for me.' And we worked 18 hours a day! That's the part they don't get when they write about executive perks."

The most notorious of the perks was, in a sense, apocryphal. Snyder didn't really have a private elevator. But he was reputed to have his chauffeur, Charles, alert a security guard to hold one elevator for him as his car approached the Simon & Schuster building. As Snyder strode toward it he would allegedly glower at anyone else who seemed about to join him. Once an executive named A1 Reuben bolted into the elevator without realizing his boss was there. Reuben pressed 13, but the elevator, oddly enough, went directly to 14, where Snyder had his office. "See?" Snyder declared. "Even the elevator knows. "

A t Simon & Schuster, profits soared, not just because Snyder was working hard. Random House, still larger than Simon & Schuster at the time but looking over its shoulder, had editors of literary distinction. Snyder's team was plugged into politics, pop culture, and anything else that could generate the next best-seller. Along with Korda, Snyder had Alice Mayhew, who went from editing All the President's Men to work on much ^ of Simon & Schuster's most distinguished nonfiction; Phyllis Grann, who graduated from mysteries to running Pocket Books, the paperback arm; and Nan Talese, who nurtured Margaret Atwood and Ian McEwan. Then there was Joni Evans, an editor of several best-sellers at William Morrow, whom Snyder had hired to handle the newly lucrative field of subsidiary rights, and whom, in 1978, he married.

Over the next decade, the saga of Dick and Joni, from its romantic beginnings to its vitriolic end, would be a central soap opera for the entire industry. How Evans started Linden Press, her own imprint at Simon & Schuster, to distance herself from Snyder at work; how Snyder's corporate rise brought her back to fill his old job as head of Simon & Schuster's adult books; how the pressure of that destroyed the marriage and led Evans to become editor in chief of rival Random House—those chapters remain all too vivid today. With Snyder, the defining aspect of them was anger—anger and a rage to win.

By this time Snyder's temper had become the stuff of legend. "Look, that's history," he pleads. "I'm a different man today. And I can tell you, I spent thousands of dollars in therapy coming to terms with that anger." The old "tantrummer," as his wife teasingly calls him, does seem positively mellow. But, for the many editors angrily fired by him over the years—so many that they used to hold a cocktail party every summer—the image of a gentle Dick Snyder is hard to square with memories of the red-faced, furious boss, spewing profanities and showering them with scorn. So intense was the pressure that three editors, either while at Simon & Schuster or soon after leaving, had heart attacks.

So intense was the pressure that three editors at S&S had heart attacks.

And yet, for those who stood up to him—and generated best-sellers—Snyder could be a loyal, even inspiring leader. Promising editors from other houses would be wooed with a routine none has ever forgotten: after inviting them over for a drink at his corporate apartment in the St. Moritz hotel, Snyder would invoke Simon & Schuster's new greatness, then stand them by the window overlooking Central Park. "Come to work for me," he would say, "and someday all this will be yours." Salaries were the highest in the business—battle pay—and for all of Snyder's bullying, he liked editors who were tough enough to make the grade. "He would accede to our passions," says Jim Silberman, former head of the Simon & Schuster imprint Summit Books. "It's something that has gone out of publishing." Simon & Schuster may be scoffed at as the commercial house—what Roger Straus of Farrar, Straus & Giroux even today calls a "quick-buck company" which was headed by a publisher who "added nothing to literature"—but as Silberman observes, "In retrospect, there was something much more vital at S&S than in publishing houses now." And for the inner circle—Korda, Mayhew, and, while she was married to him, Joni Evans—Snyder was like General Patton: tough, but exhilarating.

More than anyone else in publishing, Snyder saw over the horizon. He saw that chain stores were proliferating; rather than bemoan the demise of independents, he published more books to fill the new stores' shelves. More stores meant more sales, which meant he could pay top authors more—sometimes poaching them from other houses, which scandalized his peers—and still make money. Above all, he saw that publishing, like other businesses, would soon consolidate. And with the death of Bluhdorn of a heart attack at age 56 in 1983, Snyder saw his chance to take advantage of that trend, too.

Sn nyder was still, in one sense, naive: a \ lousy corporate politician. In the wake V of Bluhdom's death, he backed a dark horse, Jim Judelson. When the job went instead to Martin Davis, a difficult, sour man who had come up through the Paramount publicity department, Snyder had an enemy as his boss. Yet Davis realized Snyder was too good to let go, and when he began selling off the many Bluhdorn acquisitions it made no sense to keep, he saw that the cash he was stockpiling ought to go, in part, to buying book companies for Simon & Schuster.

Not just any book companies, however. Textbook companies. Snyder realized that no matter how hard he drove his editors, and how many best-sellers they published, adult books was a tippy business. Textbooks, unglamorous as they might be, were huge and steady earners with a captive audience.

Over the next decade, Snyder bought dozens of textbook companies, including Prentice Hall and other businesses, for a total of about $2 billion. Simon & Schuster was now America's biggest publisher—bigger even than Random House, which had dwarfed it when Snyder began (and which from 1980 until last year was owned by Advance Publications, which publishes this magazine). "Random House was the class Jews, Simon & Schuster the declasse Jews," says former Simon & Schuster editor Dan Green. And the declasse Jews had triumphed! A decade later, Viacom, Snyder's nemesis, would sell most of the same bundle to Pearson, the English media conglomerate, which owns Viking Penguin and Putnam, for nearly $4 billion—a huge windfall for Viacom and, for Snyder, vindication bittersweet.

In retrospect, the revolution Snyder helped begin overthrew him, as revolutions tend to do. At the time, Joni Evans and Martin Davis appeared the more immediate threats.

T he divorce proceedings lasted nearly as I long as the marriage. Snyder lost, apI pealed, lost, appealed again. And was forced, by a clearly exasperated judge, to surrender 50 percent of his marital assets— several million dollars. (Evans was forced to give Snyder 50 percent of her more modest marital assets as well.) With part of her settlement, Evans bought a weekend house just five miles from Linden Farm—a contemporary, glass-walled aerie overlooking a river—but never socializes with Snyder and, according to friends, never even thinks about him anymore. She now works as a literary agent at William Morris.

"A town car! Who doesn't have a town car? Who doesn't go to the Four Seasons?

The guy has this incredibly puritan attitude/' says Snyder's wife, Laura Yorke.

Davis was Snyder's other nemesis. The brooding chairman of what was now called Paramount phoned almost every day to offer criticism or question some decision. Davis did have some cause for ire: the Dick-and-Joni relationship had had sharp reverberations throughout the company. And when, after Evans's departure, Snyder took up with an attractive young Simon & Schuster editor named Laura rke, Davis may have had cause to insist Yorke take a job outside the house. But profits stayed high, and if there was a reason, other than personal vindictiveness, for Davis to change the name of Simon & Schuster Publishing to Paramount Publishing, no one today can say what it was. "First, it was dumb," Snyder says. "Second, it was designed to antagonize only one person: me.

"In the end," Snyder adds, "we destroyed each other professionally. I mean, he's a very rich man, and I have a happy life, but I'm doing Golden Books because of Marty Davis, and Marty Davis is doing nothing because of Marty Davis."

Davis, perhaps, is to blame for making Paramount a takeover target in 1993. It was he who spoiled Time Inc.'s friendly merger with Warner Communications, making ever higher offers that forced Warner to take on an additional $9 billion of debt to fend him off. A suitor with so much cash suddenly looked attractive to Viacom, the entertainment conglomerate Sumner Redstone had built from MTV, Nickelodeon, and Showtime. Emboldened, Viacom nearly managed its own friendly merger with Paramount—until Barry Diller played the role of the spoiler. Snyder had grown close to Diller in the Bluhdom days, when Diller was head of Paramount Pictures. Fairly or not, he was seen as a Diller supporter. When Viacom outbid Diller, Snyder might have left. But, he says quietly, "it would have meant leaving something I loved. I could never have walked away."

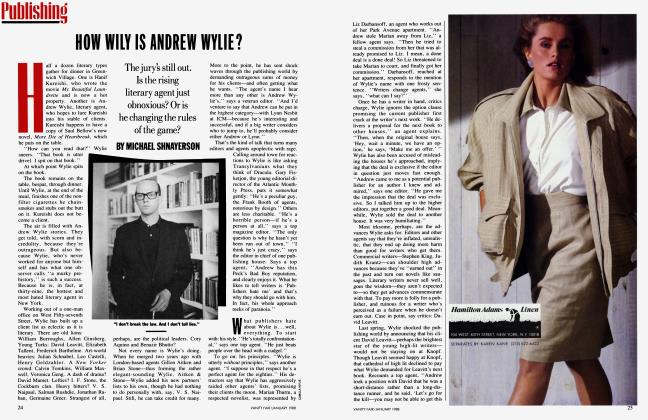

A t first, the signals from Paramount's new owner seemed encouraging. Redstone spoke of Simon & Schuster as the jewel in Paramount's crown and, at Snyder's request, restored its corporate name. Over a friendly lunch at the Four Seasons with Viacom C.E.O. Frank Biondi, Snyder asked for higher compensation, and Biondi seemed amenable. But within weeks Redstone and Biondi thought they were getting signals of a very different sort from Snyder.

Snyder, they felt, was more imperious than they could have imagined. He hired public-relations man John Scanlon to burnish his personal image—a move Davis had expressly forbidden—and demanded that the 4 years left on his contract be extended to 10, with his $1 million annual salary doubled. Biondi had emerged from the Four Seasons lunch assuming he and Snyder would walk the five blocks back to the office, only to see Snyder's chauffeur, Charles, awaiting his master at the opened door of his black town car. For a top executive in a corporation that stressed collegiality and no frills, it was an image that stuck. When the salary demands came, conveyed by high-priced lawyer Joseph Flom, Biondi and Redstone shook their heads. This guy doesn't get it.

The night before Snyder was to make his first presentation to Viacom's division heads, a corporate lawyer called him at home to ask, casually, if he would come to the meeting a few minutes early. "Dick," his new wife told him, "incomprehensible as this is to you, they're going to fire you tomorrow."

.

So they did. Snyder wandered back to his office in a daze and called his wife, who came right over. As they were crying, the phone rang: Frank Biondi. Why, Biondi wanted to know, was Snyder still in his office? "Frank," Snyder said slowly, "I've been here 32 years. It's going to take me a little while to organize my things."

The day after Snyder took charge of Golden Books—May 9, 1996—he paid I a visit to the corporate headquarters of Walmart, his biggest customer. He knew he was in a different business now, of discount consumer-goods chains. He may not have realized how different. "We made books for the children of the masses, not the classes," says Richard Bernstein. "We sold tonnage. Our customers were as likely to eat the books as read them."

Snyder expected a genial reception. He was shocked. The Walmart buyer told him that Walmart no longer believed anything Golden said, and would be just as happy if Golden pulled out for keeps. Snyder learned a new phrase that day: fill rate—the rate at which a publisher was able to keep store shelves filled.

Golden, it seemed, was so disorganized that it could not, in any expeditious manner, restock the Golden titles that sold, or take away those that failed to.

Snyder went back to his office to learn that Golden, incredibly for a book publisher, had no sales reports at all. It knew how many books went out; it had no idea what happened to them after that. Worse, Golden sent most of its books in shrinkwrapped discount packs of, say, a dozen different titles. If its warehouse ran out of one of those titles, the packs couldn't go out. It was a nightmare.

"They spent months doing due diligence," Bernstein observes.

"There were eight guys from Ernst & Young in our offices— and all of this came as a surprise to them?" Snyder retorts,

"Due diligence is 'Here are the accounts receivable; here are the accounts payable; here are the contracts—are they valid?' That's not where we saw anything [wrong]." The due-diligence team didn't look at fill rates. Or frayed customer relations. Or, as Snyder glumly terms it, "the gatekeeper problem." A bookstore, he observes, lets a publisher charge whatever he thinks the market will bear. "The [discount] store says, 'I want it at $1.29, and if you don't give it to me, someone else will.'" Here was the king of Simon & Schuster, locked in to a few pennies' profit on every Poky Little Puppy book.

If only Snyder had had a few veterans of the business—the mass-market children'sbook business, not those elegant, hardcover, Caldecott Award-winning children's books that Simon & Schuster published at $ 16— he might have been forewarned, and perhaps forearmed. Yet almost immediately, Snyder fired virtually everyone in the company's operating management. The old guard was stuck in its ways, he says. But as a result, Bernstein observes, "he entirely eliminated the institutional memory."

I nstead, Snyder turned to the world he knew. He tried to persuade Alice Mayhew to join him—and was furious with her when she refused. He had better luck with Robert Asahina, a younger Simon &

"There's nothing worse for a marriage than a man having lunch with his wife every day," says Snyder.

Schuster editor, who agreed to start an adult Golden Books line—on subjects of interest to parents of Golden Books children—for a risk-softening salary of $200,000 with a bonus provision that might yield him two times that much over his pay. To be president, Snyder hired, at a comparable salary, Willa Perlman, who had headed up children's books at Simon & Schuster and was ready for a change. "I had come to a place in my career with children's books, that books as the output of intellectual property were not enough to sustain me any longer," she explains. Golden was so ... different. "It would be like learning a new language."

Asahina, at least, was starting a line of books of the kind he knew about, for bookstores, not discount chains, so he would be unaffected by many of Golden's problems. But, like his boss, he acted as if he were still at Simon & Schuster, paying best-selling author Stephen Covey such a high advance for The 7 Habits of Highly Effective Families as a debut title that the book would manage nearly to sell out its print run of 500,000 copies—and still lose money. Perlman faced a more immediate problem. Nearly all of Golden's key licenses—for movie and TV characters—were up for renewal.

"Our Disney, our Children's Television Workshop, Barbie, Barney ..." Perlman ticks them off ruefully. These were "anchor" licenses that provided, she says, 75 percent of Golden's revenue. And due to Bernstein's haphazard management, she claims, most were ready to jump ship. (Bernstein takes exception to that. "Typically, character licenses are in the oneto three-year period, so if one made the statement that all of the licenses had less than three years left on them, sure! But what did that mean?")

Perlman persuaded nearly all of Golden's anchor licensees to re-up. But at sizable cost. When Golden chose to renew its longtime license to publish books featuring Disney characters for $47.5 million—about 10 times what Golden had paid Disney in the past, according to Bernstein—the industry was agog.

In fact, Disney's animated movies were already declining steadily in profitability. But to Golden the license seemed crucial, both for profit and prestige. "They had us over a barrel," says one Golden executive, sighing. "New management ... bad times."

Undeterred by these portents of trouble, Snyder set about building his family empire. He paid $81 million for Broadway Video, a company run by Saturday Night Live creator Lome Michaels, which owns Lassie, the Lone Ranger, Pat the Bunny, and other Golden-like icons. He commissioned new Lassie episodes for Animal Planet cable and new Pat the Bunny home videos. He looked into Golden theme parks and Golden play centers.

Snyder wanted it all, and he wanted it fast. Rather than settle for some BandAid approach to the sales-report and fillrate problems, he called for a whole new integrated financial system. Bernstein had put in a more modest sales-report system called Wisdom. But it wasn't yet up to speed. As underlings tinkered with it, Snyder ordered a vastly larger one, similar, as he puts it, to a German system called SAP. From Wisdom to SAP! But it was, Snyder concedes now, too complex and expensive to make sense for Golden Books. "It gives you a 747," he says, "when you may need a two-engine prop."

Another such mistake, says Snyder, was the brand-new, $40 million printing plant. For decades Golden had printed its own books at a Dickensian plant in Racine, Wisconsin. Virtually no other publisher in America did that, but it made sense for Golden as long as it stuck to those little Golden books and, perhaps, a few coloring and activity books. Now Snyder wanted to publish all kinds of new books. A publisher who knew the market might have jobbed out the work to factories in Asia. Instead, Snyder built a huge stateof-the-art plant—which still couldn't handle Snyder's outsize publishing plans.

As unfortunate was the decision to move most of the company's whitecollar staff from Ra] cine, where Western had been based, to Manhattan. Racine had its share of social problems, and the employment pool was small. But the importation of hundreds of workers to a new, six-story office space in New York to conjure up a new Golden Books—even as Snyder's executive team was trying desperately to whack Golden's 7,000 titles down to a manageable 1,000 or so—was, at best, an optimistic decision. It also led to oddly familiar rumors that made their way around the publishing world. Fancy offices. A personal chef. A corporate jet!

'Look at this paneling!," Snyder says in the I hallway outside his office. He knocks on L a piece of attractive, white-blond wood. "The cheapest paneling you can buy." The floors are small, he goes on, and very narrow. Because the owner of the Seventh Avenue building, Marshall Rose, sits on Golden's board, Snyder got the space cheap.

Over a deli-ordered tuna-fish-sandwich lunch in what is, admittedly, a very small executive conference room, Snyder answers the next question before it's asked. "O.K.— the chef," he says. "I said, 'Let's get a chef who will make a communal lunch, and we can use the boardroom. And we'll give lunch there every day.' Chef implies dining room—there was no dining room. Chef implies waiter—there was no waiter. And what he cooked mostly was health food."

And the jet?

"Racine is a place you cannot get to," Snyder says indignantly. "And I was not, at my age, with two little kids, going to spend all my time making air connections to Racine. So we got one-eighth of a Citation II, which we had the right to sell back. The fact was it was a tin can, the slowest jet ever made. You couldn't stand up! If you wanted to go to the bathroom, you had to back in!"

Nevertheless, as Snyder admits, all this led to an image problem. Perhaps, he says, he did get spoiled in the Bluhdorn days. All the jets, the drivers, the private apartments. "You get used to all that and don't think about the public perception of it as much as perhaps I ought to have done." As damaging, says one former Golden executive, was the stiff corporate protocol. "Golden was all about dress codes and decorums and a level of formality that was death for a company that should have been entrepreneurial."

None of it would have mattered if Golden Books had begun showing quarterly profits. Unfortunately, all the empirebuilding schemes sapped cash—eventually $300 million. And though millions of Golden books were selling, the margin of profit on each was very, very small. Much money out, very little in; quarter by quarter, the losses grew.

"I negotiated a contract.... I'm sorry if it offends some people, but it's a lifetime of work to get here."

In hindsight, Snyder may have taken on Golden at an unpropitious time. The last of the baby boomers' children were growing up; the core market was, perhaps, shrinking. Home videos and CDROMS were taking larger market shares, and children, perhaps as a result, appeared to be growing faster out of their "Golden years." Moreover, many of the discount chains Golden relied on—Caldor's, Bradlees, Ames, and the like—were ailing, victims themselves of thin profit margins. And after decades of virtually owning the market, Golden had rivals. As a result, Snyder says, mass-market children's-book sales in general were flat or going down.

It's a convincing explanation—except that Golden's main rival, the Ohio-based Landoll Company, has grown, according to its president, Martin Myers, 800 percent in the last five years. "Overall, the environment of children's books is a fantastic one," he volunteers. "And actually the profit margin on licensed-product goods is excellent." Landoll's Rugrats and Blue's Clues are two of the industry's top-selling properties. The key, Myers says, is to be lean and efficient enough to deliver the best value. "It's hard to deliver value," he says, "when you're sitting in a beautiful office overlooking Central Park."

Despite the losses, Golden's board decided, in September 1997, to recognize Snyder's efforts in the "turnaround" with a huge pay raise. The board, which included Diller, New York arts patroness Linda Janklow (the wife of literary agent Mort Janklow, who is a good friend of Snyder's), and Lome Michaels, increased Snyder's base salary of about $500,000 to $950,000—and made the increase retroactive to January 1997. According to Graef Crystal, the financial analyst who tracks executive compensation, that meant Snyder was being paid 151 percent more than the average C.E.O. of a similar-size company. But that was just the beginning.

Before taking over, Snyder had been granted 599,465 shares of Golden at $8 a share, about what Golden was traded for when the company changed hands. Ostensibly, he bought the stock; in fact, it was loaned, with the loan soon forgiven. Over the next 10 years, he could sell the stock whenever he liked and keep whatever premium it might yield over $8 a share. But if the stock plummeted, he could still cash out for $8 a share. Or, as Crystal says, "Heads I win, tails you lose!" After acquiring another 84,967 shares under the same terms in September 1996, Snyder's no-lose stake stood at $5.5 million.

In September 1997, Golden awarded Snyder a "target" bonus of 100 percent of his new $950,000 salary, then let him trade that for options worth twice that much, or $2 million. So in a year in which Golden would lose $50 million, Snyder was compensated, on paper at least, $3 million. The options were a time-delayed benefit, as was the $250,000 pension Snyder would get whenever—however—he left the company. Still, he was doing very well.

"I negotiated a contract with what would be a compensation committee if and when we took control," Snyder says adamantly. "And followed it. And I'm sorry if it offends some people, but it's a lifetime of work to get here." Had he known how much money Golden would lose over the next year, he says, he and his board—dominated by Warburg, Pincus's John Vogelstein—likely would have modified the pay package accordingly. But due to the problems he inherited, he says, Golden had no clear financial statements until 18 months after his arrival. True, except the board did know that Golden's stock had dropped 21.5 percent, in a market that over the same period had gained 48 percent.

For Snyder, the money came at a particularly apt time. That same month he moved his family into a lovely, eight-story Upper East Side town house just off Park Avenue. He had bought it for a reported $4.9 million, with a mortgage of just $1 million, and ordered $2 million of work done to it.

I n the top-floor room she uses as an ofI flee at the Snyders' town-house home, I Laura Yorke offers her own theory for why things went wrong at Golden. "I think he was so traumatized by the press he'd gotten that when he came to Golden it affected the way he managed," she says. "He had just heard and read so many times about the beast that he was that he vowed not to tell anybody they were doing anything wrong at all."

Yorke is a seasoned book editor who prides herself on her old-school line editing, and clearly would have made her way in publishing without her husband's help. Still, her relationship with Snyder has affected her career: first by forcing her to leave Simon & Schuster, more recently by inducing her to go to Golden to help Bob Asahina start the new adult line. Personally, she got dragged into the denouement of Snyder's divorce wars with Joni Evans.

In the end we destroyed each other professionally," says Snyder. "I'm doing Golden Books because of Marty Davis."

The Dick-and-Joni saga might have given another woman pause about getting involved with the boss, but, Yorke says simply, "I fell in love with him. And there's so much to love about him!" She counts the ways: brilliant, charismatic, funny, a huge heart. "And the fact that he's volatile? Well, you want to put me on the couch for six years and figure that out? Yeah, O.K., maybe I was used to it. Who knows? But the fact of the matter is that he's not like that anymore." (One former Golden executive disagrees: "He never changed. He'd have one of his screamers, and I'd just say, 'When the lithium kicks in, call me back.'") Nor, she says, does he care about corporate perks now, if he ever did. "The limo is a town car!" she says. "Who doesn't have a town car? Who doesn't go to the Four Seasons? Dick is not excessive in those ways. In his tastes the guy has this incredibly puritan attitude."

Perhaps. But as Yorke conducts a reluctant tour of her new home, decorated

by Renny Saltzman, and deliberately lets the elevator descend past the living room and dining room to the ornately woodpaneled second-floor library, where Snyder awaits, "puritan" is not the first word that comes to mind. Especially not to Marco Martelli, the high-end contractor who did the renovation.

At the Snyders' request, Martelli began work on an accelerated schedule in 1997 while architect Michael Rubenstein's plans were still being drawn up. The initial budget was about $1.3 million, though major aspects of the renovation remained unspecified. Over the 12 months the job took, Martelli says he was given 400 change orders—on paper. The added work swelled the total budget, he says, to $3,070,000. Yet when the last bills were submitted, Snyder refused to pay. "The total stiff is $1,078,000," says Martelli. Of that, about $600,000 is due to his own firm for fees, labor, and materials; the balance is due to his subcontractors. Martelli says he is suing; Snyder says he is suing him. In fact, Snyder claims, he paid 11 of Martelli's 12 monthly bills with many signed change orders. The 12th, he says, is for $500,000, with unsigned change orders, followed by a charge for $600,000 to cover worker benefits already paid. "This is a classic New York story," he says grimly, suggesting the contractor is shaking him down.

"My case is very clear," says Martelli. Architect Rubenstein agrees. "I think the court will decide in his favor," he says.

11 was on April 14, 1998, that Snyder reI alized how desperate matters had beI come. He had just returned from a 65th-birthday driving trip through Tuscany with his wife. Before he'd left, C.F.O. Philip Rowley had showed him the monthly numbers. They needed tweaking, but they weren't too bad. Unfortunately the SAP-like financial system was still unreliable. Snyder went back to his office, picked up the March numbers, and said, "My God, we're going to go bankrupt."

Sales were sharply off, cash reserves down almost to nothing, first-quarter losses frighteningly high. That was Snyder's moment of truth. Rowley had already resigned to become group finance director of the English company Kingfisher P.L.C. So Snyder took over the day-to-day running of the place.

From Golden's already reduced payroll of about 1,400, several hundred more workers were let go. The printing plant was put up for sale. The new, adult-book line, despite its growing promise, was put up for sale, too. Nearly all the brand-extending schemes were put on hold: no Pat the Bunny floor coverings, no Golden theme parks.

Grimly, Snyder reduced his New York office space from six floors to three.

The boardroom was dispensed with, as was the chef. The one-eighth share of the corporate jet was sold back.

None of it was enough to stop the stock from its sickening slide as Golden's first-quarter numbers became known. The company's nearly $300 million debt was now greater than its value: after creditors were paid, the common stock would be worthless.

Meanwhile, Golden was hit by a class-action suit from shareholders. In the suit, filed by New rk law firm Milberg Weiss Bershad Hynes & Lerach, Snyder and his team were accused of having issued deceptively rosy forecasts, quarter after quarter, all the while knowing that the company's finances failed to support them. Snyder denies the charges: the forecasts were always accompanied on 10K reports by all the obligatory numbers. But the fact that Golden was, as Snyder admits, "flying blind" without a good financial system for two years does bring into question why it felt it could be quite so upbeat.

By December, Golden was trading at about 45 cents a share, and the company had defaulted on interest payments to its senior bondholders. That was bad. By law, the whole $149 million Golden owed those bondholders was pushed from the "long-term debt" side of the ledger to the "current liabilities" column, nearly doubling the latter to $267 million. That was worse. The bondholders gave Snyder until February 16 to come up with a Hail Mary plan or be forced into Chapter 11 bankruptcy proceedings. That was about as bad as things could get.

Bl ow the deadline has come and gone. A 111 deal, after many days of waiting for 11 one last call from a reluctant creditor, has been reached. The company is saved— for now—and Snyder is still in charge. But at considerable cost. "Basically, everything

"i féll in love with him. The fact that he's vo|atile?

You want to put me on the couch for six years?"

we worked for for six months happened," Snyder reported one day in early March. "It's the happiest of possibilities—under the circumstances. But that's not to say that everyone is happy."

Happiest are the bondholders and holders of convertible preferred shares who have, in essence, traded debt for ownership of the company. The senior noteholders who were owed $149 million will get 60 cents on the dollar, and 42.5 percent of the company. The convertible preferred shareholders don't get cash, but they do get 50 percent of the equity. As a result, Golden's suffocating debt load of nearly $300 million will be reduced to $87 million, so that the company can continue. Legally, the deal is a Chapter 11 bankruptcy proceeding, since a bankruptcy judge has to bless it. But it's the mildest sort, because the bondholders and management have agreed to the terms.

Not consulted were the shareholders of Golden common stock. By the terms of the deal, to make the math work, the common stock will be annulled. Golden is a more tightly held company than, say, IBM: perhaps only hundreds, rather than hundreds of thousands, of people own common shares of Golden. But anyone who does just lost his stake. "Don't forget," Snyder says, "buying stock doesn't mean you make money."

The original investors, Snyder hastens to add, will have their preferred stock

wiped out, too. So Warburg, Pincus has lost perhaps $60 million of the original $65 million purchase price, Diller and Snyder the balance. But they, at least, get the remaining slices of the new pie: 5 percent equity for Snyder, Diller, and Warburg, Pincus, 2.5 percent in addition for Snyder himself. "He's being given 2.5 percent for having taken the company into bankruptcy—that's a hell of a reward," says Bernstein, who as the owner of 15 percent of Golden's common shares has lost $40 million and says he may sue to block the deal.

Snyder has surrendered the $5.5 million in stock options that Golden granted him. He's also lost the $2 million in "target bonus" stock options he got in September 1997, since that stock was unprotected and is now worthless. And at no point, he says, either before or during the tailspin, did he sell a single share of stock. "I'm committed to this company," he says. "I've lost money along with it; not until it prospers will I prosper, too." For good measure, he's agreed to a salary cut.

Other costs are more personal. Last fall, Barry Diller resigned from the board. In the margin of a letter requesting comment, he writes, "It's all a great disappointment to me, and I decided that I would sever my relationship to the investing partners that went into [Golden] and with it, hopefully, any involvement in their and D. Snyder's affairs now or in the future." Linda Janklow, too, has resigned. Snyder's senior hires continue to leave: the C.F.O. hired to replace Rowley last year left in January; Asahina has gone to be the editor in chief of Broadway Books; and now that the adult line is being sold to St. Martin's Press, Laura Yorke may follow it there, though that leave-taking would be merely professional.

But Snyder's eyes brighten at the suggestion that he is, in a sense, where he was when he and Korda took over a bereft Simon & Schuster and had to be scrappy to make it survive. "That's exactly right," he says. "Thirty years later, we're going to have to be scrappy. And nimble. And fleet. But we can do it."

Humbled at last, with nothing to lose, perhaps he can.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now