Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowCALLAS IN LOVE

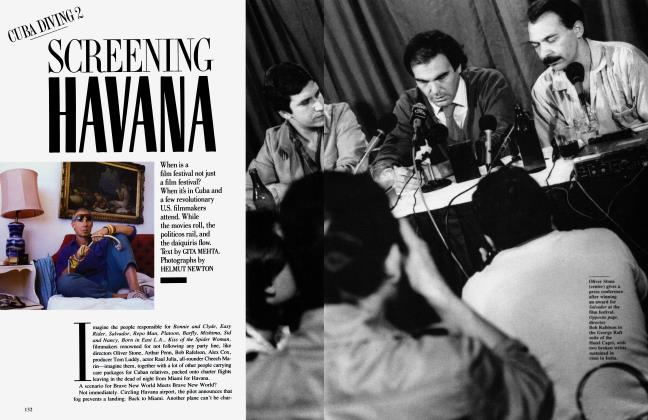

In 1959, when Maria Callas met Aristotle Onassis, she was an opera icon overwhelmed by her career. The shipping tycoon gave her a haven of pleasure, sun, and sea, then nine years later stunned the world by marrying Jacqueline Kennedy. But exclusive interviews with Callas in a new biography, by STELIOS GALATOPOULOS, reveal that their affair was not the soap opera purveyed by the media, starring Onassis as villain and Callas as brokenhearted sacrifice; it was an amorous friendship that outlasted his cold-bloodedly contractual Kennedy marriage and always took second place, in Callas's heart, to her supreme art

STELIOS GALATOPOULOS

Once you're married, the man takes you for granted, and I do not want to be told what to do. My own instinct and convictions tell me what I should or should not do. These convictions may be right or wrong, but they are my own.

—Maria Callas to Stelios Galatopoulos.

On June 17, 1959, London saw its first performance in more than 90 years of Cherubini's Medea, which both Beethoven and Puccini had declared a masterpiece. Singing the title role, Maria Callas liberated the English from their customary reserve.

She had resurrected the opera in Florence seven years earlier; now she made it her own.

I had met Callas in 1947, when she was 23. By then she had already been studying music seriously for a decade. "My mother was the first person who made me realize that I had an extraordinary musical appreciation," she told me. "It was always put into my head that I had it—and that I'd better have it." Later she added, "I can't complain. But to load a child so early with responsibility is something there should be a law against.... It's not a special toy—a doll or a favorite game—that I remember but the songs that I was made to rehearse time and time again, sometimes to the point of exhaustion, so that I would shine at the end of a school year. A child should not be taken away from its youth for any reason—it becomes exhausted before its time."

But Callas also pushed herself—relentlessly. Her desire to create great, beautiful art took her over, as Medea did, as many roles would. In April of 1939, she had made her debut as Santuzza in Cavalleria Rusticana. Her teacher, years later, recalled her determination to excel. "At rehearsals she would listen as if in a trance, and sometimes she would walk nervously up and down the room repeating passionately to herself, 'I'll get there one day.'" One critic, remarking on the "sensitivity" of her performance, noted that "the tears in the voice are very much in evidence."

As we grew closer, I saw the tears, the will—and the regrets.

She introduced me to her husband, Giovanni (Gian) Battista Meneghini, whom she married in 1949. I visited at their villa on Lake Garda in Sirmione, Italy. In 1957, Maria and I spent hours talking during her engagement with the La Scala company at the Edinburgh Festival. Certainly, you could say, there were flaws in her character. Although material gain was of secondary importance to her, she was governed by ambition, obstinacy, single-mindedness, and a touch of selfishness. These idiosyncrasies could make her less than endearing. But her shortcomings were substantially redeemed by her warmth, kind heart, tolerance, and compassion. Ghalatia Amaxopoulou, who knew Callas at the Athens Opera, said, "Maria was natural, quiet, and kind. A good and loyal friend with a straight character ... she always had the courage of her own sincere convictions. She could not tolerate insincere, deceitful people ... never pried into other people's business.... Everybody really admired her, but many, deep down, hated her for her success, for her great talent... and by undermining her they strove to destroy her artistic career."

Excerpted from Maria Callas: Sacred Monster, by Stelios Galatopoulos, to be published in March by Simon & Schuster; © 1999 by the author.

At first, our conversations rarely moved beyond art. Maria's existence had been all work; her voice—no immaculate natural gift—was a creation of perseverance and painful, taxing industry. She had little time for her personal life, a fact which clearly troubled her. Although she loved to see people marry, she wasn't certain of her judgment in the world offstage. "I am not a good matchmaker," she conceded to me after one overeager attempt.

Onstage that didn't matter. I was allowed to watch Medea from backstage in London on opening night. I saw Callas's lithe figure, cloak trailing behind her, venture from her dressing room to wait for her entrance. She seemed nervous, lost, oblivious as she prayed quietly and crossed herself in the manner of the Greek Orthodox Church. She became Medea.

Her cue followed, and Callas, whose eyes were heavily rimmed with black, knocked gently on wood, swept up her cloak to cover her face, and made her entrance. I was enthralled but grew nervous after the interval, when Medea attempts to kill her children. Callas, brandishing a knife, her face twisted by angry despair, heaved the weapon away. Knowing that she was shortsighted (without glasses she could not see the conductor), I began to worry. She would soon have to pick up the weapon again. Meanwhile, Medea ran up the steps to the temple, cursed her enemies, and with a fearless sixth sense found the knife without a pause.

That night Aristotle Onassis, the millionaire shipping magnate and owner of Olympic Airlines, and his wife, Tina, gave a party at the DorChester. Maria arrived at one A.M. with Giovanni. Decorated in pink, the ballroom, with its two orchestras, exuded elegance and grandeur. Around three A.M., when the Meneghinis said their farewells, Onassis extended an invitation to Maria and her husband to join him for a cruise on his luxurious yacht, the Christina. Maria declined.

Yet a little more than a month later, despite complications, cancellations, and perhaps forebodings, Maria—with a superb cruising wardrobe from Biki of Milan—and Giovanni boarded the Christina in Monte Carlo. "You, Maria," actress Elsa Maxwell had written in a note beforehand, "are replacing Greta Garbo, who is much too old now for the Christina. Good luck. I never liked Garbo, but I loved you."

Maria was transformed by the sun, sea, and her host. The tension and exhaustion which had plagued her were replaced by a new freedom, a lightness. She rested, soothing the vocal problems which had become more pronounced during her recent, particularly tumultuous artistic life. Maria, the opera icon of the century, was in demand, yet also in danger. She was feuding with or exiled from some of the opera world's major institutions, including La Scala in Milan and the Metropolitan in Manhattan. Yet gradually her cares and tensions fell away— along with her halfhearted attempts to feign attentiveness to Meneghini, whose management of her career had exacerbated many of her professional crises. Meneghini was shocked by the activities on the Christina. "These people appeared to be a little crazy," he later wrote. "Several of the couples changed partners. The women, and also the men, often sunbathed nude and played with each other quite openly and in front of everyone."

"My dear knowledgeable lady," Maria advised an onlooker, "life is too short to worry about other people's matrimonial problems."

Onassis, as he was known to do, increasingly drew Maria's attention, not only with his care for her, but also with his attentiveness toward Winston Churchill, who was a guest on the yacht as well. Onassis played cards with the elder statesman and was ready to assist with even his humblest needs. "On board the Christina," she would later tell me, "Churchill had everything, of course—male nurses as well as his wife and others. But Ari was much more than the perfect host to him. He was the perfect friend, always ready to amuse him and assist in every way possible. When I remarked to Ari how touching I thought his veneration for Churchill was, I got a marvelous answer: 'We must remember that it was he, the man of our century, who saved the world in 1940. Where would we all be today without this man?' So there was much more to Ari than met the eye."

Portofino and Capri were the first ports of call. Then the Christina sailed through the Isthmus of Corinth to Piraeus and eventually anchored in the Bay of Bosporus, where Meneghini saw the future revealed. "Destiny destroyed my life," he revealed many years later, "the day the patriarch Athenagoras received Onassis and his guests. The patriarch knew of both Onassis and Maria Callas. I do not know why, but speaking to them in Greek, he blessed them together. The whole scene looked like the patriarch was performing a marriage ceremony."

"In Monte Carlo, where the cruise began," Callas told me, "I was very impressed by Aristo's charm, but above all by his powerful personality and the way he could hold everyone's attention. Not only was he full of life, he was a source of life. Even before I had the chance to talk to him alone for any length of time, I began to feel strangely relaxed. I had found a friend, the kind that I'd never had and so urgently needed."

Within three hours of the conclusion of the cruise, the Meneghinis were in Milan, having flown from Nice in one of Onassis's private planes. There was no conversation between them except for Maria's news that she would be staying, alone, in Milan.

Two days later, according to Meneghini, Maria summoned him to Milan and told him bluntly that their marriage was finished. She had decided to stay with Onassis, who arrived at 10 that evening to talk things out.

For the next meeting, Onassis and Maria traveled to Sirmione. Onassis had apparently been drinking whiskey all the way from Milan, and the men nearly came to blows. At one point Onassis accused Meneghini of attempting to deprive Maria of her happiness. Meneghini retaliated by calling Onassis all the abusive epithets he could summon. "Yes," replied Onassis, "but I am also a powerful millionaire, and the sooner you get it into your head, the better it will be for everybody. I will never give up Maria for anyone or anything—people, contracts, and conventions can all go to hell.... How many millions do you want to let Maria go free? Five, ten?"

On the following day, Maria asked Meneghini for her passport and the little statue of the Madonna she always kept with her in the theaters where she performed. Then she arranged a legal separation. "I saw in Ari the type of friend I was looking for," she told me. "Not a lover (a thought that never even crossed my mind in all the years I was married), but somebody powerful and sincere whom I could depend on to help me deal with the problems I had had for some time with my husband. I knew no one else capable or willing to give me this support.

"I believed," she continued, "that my husband would see to all my affairs, other than artistic—that was strictly my department— and comfort and protect me generally, so that I could isolate myself from everyday bothers. This may sound selfish on my part, but it is the only way I can serve art with sincerity and love."

The balance between Callas the artist and Callas the human being had always been uneasy. "There are two people in me," she once remarked. "Maria and Callas. I like to think they go together, because in my work Maria is always present. Their difference is only that Callas is a celebrity." The collaboration, however, depended upon Maria's willingness to serve Callas with total dedication. With Onassis, the woman was for the first time allowed to dominate the artist.

"Our friendship," Maria told me, speaking of Onassis, "was further strengthened as the confrontations with my husband were becoming more complicated. [Our relationship] subsequently became more passionate, but only included physical love after I broke with my husband.... I had been brought up on the Greek moral principles of the 1920s and 1930s.... I have always been an old-fashioned romantic.

"Our love was mutual," she emphasized. "Ari was adorable ... and his boyish mischievousness made him irresistible and, only occasionally, difficult and uncompromising. Unlike some of his friends, he could be generous (and I do not mean that only materialistically) to a fault and never petty. Obstinate he was, and quite argumentative, like most Greeks, but even then he would eventually come round and see the other's point of view."

Soon after the cruise, Meneghini found out from one of Maria's doctors who had examined her that her heart, which had been a concern, had returned to normal and that her blood pressure—always dangerously low—was up to 110. Ironically, the doctor told Meneghini that he should thank the Lord that his wife had taken a holiday.

Before long, unfortunately, Maria's health deteriorated. Her blood pressure again dropped, and a sinus ailment worsened, affecting her singing considerably. These illnesses put her on edge, and her ragged nerves were further aggravated by the uncertainty of her relationship with Onassis. Yet it must be stressed that it was because of such difficulties, which undermined her selfconfidence, that she had turned to Onassis.

"I had the feeling of being kept in a cage," Maria would tell me. "I had become prematurely dull and old." She always tried to refute the idea that her relationship with Onassis, which had begun as she was starting to curtail her career, had led her to sacrifice everything to be with him. To her dying day, Callas never sacrificed even a minute fraction of her art for anyone or anything. And she wanted this understood.

As she began to place fewer demands on herself, Maria's health stabilized. Once more she was able to sing without tears. In 1960, she was delighted, therefore, to accept an invitation to sing in Greece, the country of her birth, where she had not performed since early in her career. (Her family had moved to New York when she was a girl.) Ultimately, it was decided that she should sing Bellini's Norma, the opera which had provided her signature role. Onassis was there, in the country he shared with Maria, to admire her. The Christina, in celebratory illumination, was anchored in the sea inlet of the nearby village, Old Epidaurus. An estimated 18,000 Greeks came to fill the vast classical theater at Epidaurus to its capacity. As the Druid priestess she looked so regal that the audience gasped, then stood for an ovation. Two white doves (ancient Greek symbols of love and happiness) were released in the audience and landed by the footlights before disappearing into the nearby forest.

Maria, who had not yet sung a note, was so deeply moved that her first phrases in the opening recitative were uneven, yet still they were poignant enough to bring tears. At the end of the performance, a wreath of laurel was placed at the feet of Greece's daughter.

When I ran into her on the island of Tinos in the Aegean, where Onassis had brought her between performances of Norma, Maria was in high spirits. Dressed simply in black, with a black chiffon scarf, she looked much younger than her 36 years. More fun than before, she dared to be outspoken about herself.

Onassis generally was friendly and amusing in his own teasing way. Yet, in his absence, Maria would avoid mentioning him. About Meneghini, she was more vocal, occasionally. When a woman mentioned to her, in a rather patronizing manner, that she had it from "good sources" that Maria would be returning to her exhusband, Callas did not hold back. "Not me," Maria snapped. "That stingy old man does not need a wife." Then, regaining her composure, she added, "My dear knowledgeable lady, life is too short to worry about other people's matrimonial problems." As she headed back to the Christina, she brightened considerably. "It is wonderful to be happy and know it right at the time you are," she told me.

In July 1961, Maria was again sailing with Onassis to Greece. He had bought a small uninhabited island named Skorpios, near Lefkas in the Ionian Sea. His intention was to build a splendid country house and turn the island into his private estate. During Callas's stay, she and Onassis often visited Lefkas, where in August a festival of folk dancing and singing takes place. One day Maria quite spontaneously participated in the festival, singing "Voi lo sapete, o mamma" from Cavalleria Rusticana and a few traditional Greek songs. Ten thousand people saw her off as she sailed away.

Invigorated and feeling all the better for her holiday, Maria returned to her apartment on the Avenue Foch in Paris. In November she bought a much bigger and more beautiful place on the Avenue Georges Mandel.

Ever since Callas's separation from her husband and the beginning of her close association with Onassis at the end of 1959, the international press persistently, if not very fruitfully, followed their every move. Once the immediate upheavals of their respective marriages were more or less sorted out, neither was at all willing to talk publicly about their relationship. What the media managed to get out of them was no more than the cryptic statement "We are good friends_Unless our friendship is giv-

en deeper significance there is no spice." They were, to be sure, constant companions when their work permitted, but contrary to reports from time to time during the next eight years that their marriage was imminent, no such step was ever taken. As the years went on, this friendship between Callas and Onassis became a puzzle of the Western world.

Calias's personal life, after Onassis's surprising 1968 marriage to Jacqueline Kennedy, was not as hapless as some have described it. She never lost touch with Onassis, who resumed their relationship a month after his wedding. At first, Maria's feelings were divided, between a proud reluctance to have anything to do with her old companion and the longing to be with him. Onassis teased her: "You have nothing against me except that I, one fine day ... went and got hitched. Well, here I am and you can't say that I got hitched all that much.

"You, Maria," he continued, "were quick to comment that I was as beautiful as Croesus and that I would make an excellent grandfather to my bride's children."

Maria, bemused, protested that she merely wanted to remind him that Jackie was young.

The fact that Maria and Onassis could continue their friendship is at least partially due to his relationship with his new wife. There is little doubt that the marriage was based on a contract in which both parties drove a very hard bargain. Nevertheless, it did not take Onassis too long to realize that Jackie left a great deal to be desired. She and her new husband were together only occasionally, but this seems to have been part of the agreement. Onassis, a man of genuine largesse, even managed to stomach Jackie's pathological extravagance. (She spent one and a half million dollars on herself in the first year of her marriage, and other vast sums in redecorating the Skorpios house.)

CONTINUED ON PAGE 264

"He did not marry for love." Maria Callas said of An s union with Jackie Kennedy.

CONTINUED FROM PAGE 237

In February 1970, however, Onassis found his pride wounded when a letter, written by Jackie to her former companion, Roswell Gilpatric—a married man—appeared in the international press. It had fallen into a dealer's hands and was published before Gilpatric could recover it. Written by Jackie a few days before her wedding, it was of some concern to Onassis, for it ended with these words: "I hope you know all you were and are and will ever be to me."

Onassis's concern grew when Gilpatric's wife filed for divorce on the day after the letter was published. Embarrassed, he found refuge in Maria, whom he saw much of during several consecutive days. After the two were photographed together at Maxim's, Jackie rushed to Paris to reclaim her husband.

At about this time, speaking to David Frost on American television, Callas acknowledged that she still considered Onassis a close companion and said that "he also considers me his finest friend." She continued: "That is a lot in life. He is charming, very sincere, spontaneous. I think he always will come to me with his problems because he knows I would never betray any confidence: I, too, need his friendship."

Onassis saw more and more of Callas, for he had many troubles. His daughter, Christina, had made a disastrous marriage with Joseph Bolker, a real-estate agent 28 years her senior, and Onassis had cut her off from her trust. Jackie was hopeless when it came to providing the support he needed. She was unwilling to involve herself in any of his worries or to comfort him. He set about finding a way to end the marriage and reduce, to the bare minimum, Jackie's legal claim on his estate.

Time, however, was to prevent Onassis from going through with his divorce. The death of his only son, Alexander, in an airplane accident all but broke him emotionally, and the serious deterioration of his health robbed him of his extraordinary energy. He died in Paris in March 1975 and was buried on Skorpios.

It was a terrible blow to Callas, even though she was prepared for it. Her friend had been suffering from polymyositis (myasthenia gravis), an incurable though not always fatal disease, and had already lost the function of some muscles.

In the first week of January 1975, Onassis had visited Maria in Paris on his way to Athens from America. At the beginning of February he collapsed in Greece and was taken to the American Hospital in Paris for a gall-bladder operation. Maria visited him once, but she was in Florida when he died.

After his death, followed by Callas's two years later, all legal barriers were lifted and some writers and journalists began to misconstrue events in their life together. Lacking any real knowledge of the woman and ignoring the artist, writers gave the affair undue prominence, as if it had been the most important event in Callas's life, thereby obscuring the real significance of one of the most influential artists of the century.

The tendency has been to turn Callas the woman into a stereotypical soap-opera victim. Within this contrived scenario Onassis was preposterously cast as principal villain—the jumped-up peasant who became a multimillionaire but remained a confirmed philistine and male chauvinist pig, and who allegedly ruined Callas's career before abandoning her to die of a broken heart.

Maria Callas put all the myths to rest during an interview with me. She did not conceal the volatility of their friendship. "It is true that I had quite a few arguments with Ari.... You see, before I met Ari I had not really experienced lovers' tiffs, and being by nature rather shy and introverted (when I am not on the stage) I was losing my sense of humor, not that I have much." She continued. "It took time, but once I understood ... his character, by and large I accepted it, even though in part I still disapproved of it.

"Ari's upbringing had been unusual. His family were well-off and cultured, and although Greek, quite prominent in Turkish society.... As a young man he had seen and known suffering and had used his wits to survive. Whereas he matured as an outstanding businessman, in some other ways— in personal relationships—he did not. Relatively speaking. He liked to tease, but if you dared pull his leg in an effort to fish for compliments, he would sometimes retaliate like a tiresome schoolboy.

"At a dinner party, I think it was at Maxim's, while we were having a pleasant time and everybody seemed to be in a very jovial mood, one of our closest and most likable friends ... cast a teasing remark, saying, 'You lovebirds, I'm sure you make love often.' Or words to that effect.

"'We never do,' I commented, smiling and winking at Aristo. His reaction was incredible. Abruptly, but fortunately in Greek, he declared that if that was the case he would make love to any woman except me, even if I were the last woman on earth. I was very upset, not so much over what he had said, but the way he said it—particularly when I sensed that other people in the party understood Greek. The worst of it was, the more I tried to silence him, the more he went on about it. It took me several days to bring myself to mention this incident. He said that it was he who was embarrassed in the first place. I explained that what I had said was clearly a normal understatement which conveys more effectively the opposite meaning. 'Right,' he answered, 'and mine was a normal overstatement which also conveys, even more effectively than yours, the opposite meaning.'

"There were other similar incidents. Although his English was good, especially in business matters, in ordinary conversations when he was arguing, it could sound abrupt and sometimes brutally so; his English was a literal translation from the Greek, the language he thought in with an Eastern mentality. This also explains his relative lack of sophistication when he was with close friends. He considered this type of social sophistication as affectation, if not sheer hypocrisy, and he expected me to stand up to him and give him as good as I got. This was not because he was a male chauvinist. On the contrary, he liked the company of women very much and really all his life he trusted them more and preferred to confide in them rather than in men.

"I really had only one thing against him," she went on. "It was impossible for me to come to terms with his insatiable thirst for conquering everything. I appreciate achievement immensely (at one time I considered it the only reason for living, but then I was young and unwise), but with him this developed into something else. It was not money—he had plenty and lived like the richest man in the world. I think his trouble was this continuous search, his restlessness to accomplish something new, but more for the bravado than the money."

"This bravado," I asked, "did it extend to people? It was, after all, widely believed that Onassis always wanted to be seen in the company of famous people and beautiful women."

"I would say," Maria answered, "that this observation was partly true. He certainly liked this kind of thing, but only with people that he also genuinely liked or admired. And let me add that he was also friendly and generous to poor and unknown people, provided he liked them. He would never forget an old friend, especially if he had come down in the world. There was never any publicity for this side of his character, as it does not make interesting news generally. What I cannot comment on with authority is how honest his business transactions were.

"When his son died he lost the craving to conquer, which was his lifeblood. This attitude of his had been basically the cause of our arguments. Of course, I tried to change him, but I realized that this was not possible, any more than he could change me. We were two independent people with minds of our own and different outlooks on some basic aspects of life. Unfortunately, we were not complementary, but we understood each other sufficiently to make our friendship eventually possible. After his death I felt a widow."

By this stage of our interview, I had summoned up enough courage to be more personal: "But why did you not marry him?" I asked Maria.

"Oh, it was partly my own fault," Maria interposed. "He made me feel liberated, a very feminine woman, and I came to love him very much. But my intuition, or whatever you call it, told me that I would have lost him the moment I married him—he would then have turned his interest to some other, younger woman. I also sensed that he too knew I could not change my outlook on life to fit in with his, and our marriage would probably have become, before long, a squalid argument." She continued: "Make no mistake, when he married I felt betrayed, as any woman would, though I was more perplexed than angry, because I could not understand for the life of me why, after so many years together, he married another."

Maria then chuckled and said, "No, he did not marry for love.... It was more a marriage of business convenience. I have already told you that he was afflicted with a predilection for conquering everything.... I really could never come to terms with this philosophy."

Realizing that Maria was in a genial mood, I probed further, inquiring about a theory I had heard—that Jackie's mother-inlaw, Rose Kennedy, had arranged the marriage in exchange for Onassis's financing of a future Kennedy presidential campaign.

"You seem to be well informed," she answered, "better than I am. Are you in the C.I.A. or something? Well, anyway, I do not regard that as a marriage made in heaven." Then, shaking her head and pointing a finger at me in feigned remonstrance, she exclaimed, "Let's leave it at that, shall we?"

Nevertheless, I questioned her further regarding Mrs. Kennedy. Maria became serious again and answered by saying that Onassis came back to her not long after his wedding, literally in tears over the mistake he had made.

"At first," she said, "I would not let him into the house. But, would you believe it, one day he persistently kept on whistling outside my apartment, as young men used to do in Greece 50 years ago. So I had to let him in before the press realized what was going on in Avenue Georges Mandel.

"With his return, so soon after his marriage," she continued, "my confusion changed into a mixture of elation and frustration. Although I never admitted to him that I believed he was going to divorce his wife, I felt that as our friendship at least had survived his marriage ... Anyway, I continued to see him from time to time, and during my concert tours in 1973-74 he always sent me flowers and telephoned."

"You said that when he died you felt a widow. How do you feel about him now?"

"The word 'widow' is a figure of speech. Naturally I miss him. I have missed other people in my life, as everybody does, for much less. But this is life and we must not make a tragedy of those we have lost. Personally, I prefer to remember the good times, however few these usually are. One of the best things I have learned in life is that people should be assessed by taking into account both their good and bad points. I hope I will be, too. It is the easiest thing in the world to destroy almost anyone by considering merely the flaws in their character."

"So you feel no bitterness towards him?"

"None whatever," she replied. "I could have, if I were inclined to such feelings. But there are two kinds of people: those who remain bitter and those who do not. I am so happy that I belong to the second category. As far as Ari is concerned, of course I miss him, but I do try not to become a complete sentimental fool, you know?"

Maria continued to be pleasantly sociable, but she was really miles away until I said, "A penny for your thoughts."

She stared at me and then, winking, exclaimed that her thoughts were worth much more.

"I quite agree," I replied, "but that is all I have." Then, resting her chin on her hand, she began again. "For some time at the beginning of our relationship we were blissfully happy. I also felt secure and even unperturbed about my vocal problems— well, for the moment. As I have already told you, I was learning, for the first time in my life, how to relax and live for myself, and even began to question my belief that there was no life beyond art.

"This frame of mind was relatively shortlived, as I discovered that many of Ari's principles, his code of practice, were seriously at variance with mine. I found myself unstuck. How can a man who really loves you at the same time have affairs with other women? He couldn't possibly love them all. For some time it was only a suspicion, which I tried to dismiss, but evidently I could not, and it was out of the question to accept it into my moral code in any circumstances.

"The role of the betrayed wife," she continued, "was not in my repertoire.... We were not, therefore, compatible for marriage to each other ...

"Ari, who did love me ... also knew that sooner or later we would have been at daggers drawn had we married.... I would have preferred that he would not have married somebody else. But that was an unusual marriage whichever way you look at it. Nevertheless, at the time, I was terribly upset and thought him a proper bastard and used other epithets I do not care to repeat. It was later, when he came back and when obviously I began to regain my lost pride, that I was able to put things in a wiser and more realistic perspective."

I realized that Maria had become familiar with the real reason for, and conditions of, Onassis's marriage, after he returned to her. This realization undoubtedly played a great, if not crucial, part in her decision to accept him back into her life. Although this marriage contract was not made public, it was occasionally mentioned in the press after Onassis's death in 1975. Friends of his professed to have known about it and exmembers of the Christina crew claimed actually to have seen it. Apparently the marriage was to last seven years, at the end of which Jackie would receive $27 million. It also stipulated that she would not be required to sleep with her husband, nor be obliged to have children.

Onassis hardly ever lived under the same roof with his wife. Even when he was in New York for considerable periods, he stayed at the Pierre hotel, not far from his wife's sumptuous 15-room apartment. The press was always told that Mrs. Onassis was redecorating—a process that seemed interminable.

Without any prompting from me, Maria, half smiling, continued to talk about her relationship with Onassis—as if she wanted to get it out of her system. "After his marriage we never quarreled," she said, her voice gaining strength.

"We discussed things constructively," she said. "He stopped being argumentative. There was no longer the need to prove anything, either to ourselves or to one another. Furthermore, his business affairs took a turn for the worse_His health was de-

clining, and the death of his son almost certainly dealt him a final blow.

"During this difficult period he always came to me with his worries. He was in great need of moral support, which I gave him in the best way I could. I always told him the truth and tried to help him face reality—he appreciated that. Also, he was absolutely set on getting a divorce, sooner rather than later, but time proved against him.

"When I saw Ari on his deathbed at the hospital," she told me, "he was calm and I think at peace with himself. He was very ill, and he knew that the end was near, though he tried to ignore it. We did not speak about old times or much about anything else, but mostly communicated in silence. When I was leaving (I visited him at his request, but the doctors asked me not to stay long), he made a special effort to tell me, 'I loved you, not always well, but as much and as best I was capable of. I tried.'"

A little moved by her recollection, Maria smiled warmly and quietly said, "That's how it was."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now