Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowTHE EARLY YEARS: 1914~1936

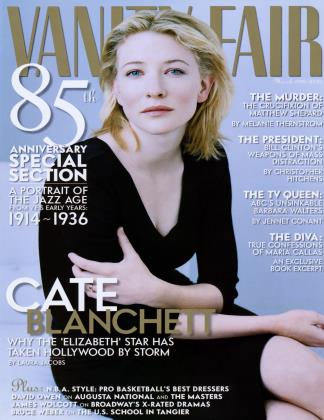

VANITY FAIR

5TH-ANNIVERSARY SPECIAL SECTION

Photograhps by, EDWARD STEICHEN, MAN RAY, CECIL BEATON, ANTON BRUEHL, HORST P. HORST, GEORGE HURRELL, BARON DE MEYER, AND OTHERS. Illustrations by RALPH BARTON, PAOLO GARRETTO, MIGUEL COVARRUBIAS, FISH, WILL COTTON, AND MORE.

ONCE UPON ATI ME. BEFORE THE INCOME TAX, THE GREAT WAR, AND PROHIBITION, MR. CONDE NAST BOUGHT A MAGAZINE

called Dress, a potential rival to his four-year-old Vogue. A few months later, in 1913, he paid $3,000 for a musty British social, literary, and political review titled Vanity Fair, named after both the sinful place in John Bunyan's 17th-century allegory The Pilgrim's Progress and William Makepeace Thackeray's 19th-century satirical novel. Crossbreeding his two acquisitions, Nast created Dress & Vanity Fair, a hydra-headed flop. To salvage the situation, Nast sought advice from the most cultivated, elegant, and endearing man in publishing, if not Manhattan, Frank Crowninshield.

The upper-crust aesthete—who, earlier the same year, had helped organize the landmark Armory Show, a succes de scandale which introduced Cubism to the American public—offered a remarkably simple solution. "Your magazine should cover the things people talk about," Crowninshield told Mr. Nast.

"Parties, the arts, sports, theatre, humor, and so forth." Nast at once anointed Crowninshield editor, and agreeing to ditch the first half of the old title, the publishing tycoon launched Vanity Fair in January 1914. In his first editor's letter that March, Crowninshield confidently proclaimed that "young men and young women, full of courage, originality, and genius, are everywhere to be met with."

Miraculously, geniuses did materialize in "Crownie" 's offices with alarming frequency. Dorothy Parker, who happened to be toiling at Vanity Fair as a caption writer, sold her first poem to the magazine. Robert Benchley, setting off from the Harvard Lampoon, also wound up at Crownie's silver-leafed door. At one point, the humorist was even managing editor—but then, so were the clever brunette Helen Brown Norden (Conde Nast's mistress), as well as her blonde antithesis, Clare Boothe Brokaw, who grabbed the post from her jilted lover, Donald Freeman, just after his death in a car wreck. And to varying degrees Crowninshield discovered or championed e. e. cummings, Walter Winchell, Noel Coward, Edmund Wilson, P. G. Wodehouse, Alexander Woollcott, Cecil Beaton, Edward Steichen, George Hoyningen-Huene, and Man Ray. Generously assuming that his 90,000 readers already shared his own avant-garde tastes, in 1917 Crownie ran a poem by Gertrude Stein, and he routinely reproduced works by Matisse, Maillol, and Picasso long before any mainstream American magazine dared—and over Nast's heated objections.

From 1921 to 1927, Nast and Crowninshield actually roomed together in a Park Avenue duplex—"I suppose people thought we were fairies," the publisher said—a situation providing the editor with posher accommodations than he could otherwise have afforded, and his boss with access to Crowninshield's far-flung and comprehensive social connections. Omnivorously embracing everyone from Harry Houdini and Gypsy Rose Lee to Mrs. Astor and the "rich as mud" Mrs. Harry Whitney, Crownie was, in fact, memorialized in his 1947 New York Times obituary as "one of the true founders of cafe society." And it is very much this composite, cosmopolitan, glittering universe that V.F defined, tweaked, mirrored, and celebrated in its irreverent, sophisticated pages.

The magazine's jaunty ethos of mixing, matching, and homogenizing personalities from different classes, races, and sexes (as long as they were brilliant, beautiful, rich, or talented) was nowhere better expressed than in illustrator Miguel Covarrubias's "Impossible Interviews," imaginary pairings of such unlikely duos as Greta Garbo and Calvin Coolidge. Though V.F elevated all of its elect to the same celestial plane, once apotheosized, nobody was sacred. Thus the glossy mirthfully printed humbling beach shots of George Bernard Shaw and Otto Kahn, and in 1918 it enshrined Henry James in its Hall of Fame, only to list him five years later among "The Ten Dullest Authors."

What, then, killed Vanity Fair, dead at 22 in the year 1936? A victim of the Depression, the magazine lost advertisers—whose existence Crowninshield had always ignored anyway. But Vanity Fair had also fallen out of sync with the times. By the 30s, with the economy and Fascism at the forefront of readers' minds, subscribers gravitated more to no-nonsense news coverage than to arch V.F pictorials such as "Who's Zoo?," which likened Mussolini's face to a monkey's. Nast contemplated emasculating Vanity Fair by turning it into a magazine called Beauty. But instead he folded it, along with Crowninshield, into Vogue. How bewildered the erudite Crownie would be to learn that, 85 years after his installation as editor—and 16 years after Vanity Fair's resurrection into its current incarnation—today's reading public is less familiar with Bunyan and Thackeray than with the periodical that once promised to "ignite a dinner party at fifty yards."

AMY FINE COLLINS

One of magazine history's true grandees, Frank Crowninshield, shown in the Conde Nast offices near the end of World War I, edited Vanity Faif for 22 heady years, is philosophy, coined in 1914: "Take a dozen or so cultivated men and women; dress them becomingly; sit them down to dinner. What will these Bople say? Vanity Fair is that dinner!"

1914

Irving Berlin, a 26-year-old Russian immigrant who broke into the music business as a singing waiter, would go on to become the father of American popular song, conjuring standard after standard ("Alexander's Ragtime Band," "God Bless America," "White Christmas"). Observed Vanity Fair, "The swing of his airs has made thousands dance. He has probably caused more insomnia than any living man." Photograph by Brown Brothers.

CUT OUT ALL THIS FOOL BUSINESS OF DIET AND DRUGS AND NITROGEN. DRINK ALL YOU LIKE. SMOKE ALL YOU CAN—AND YOU'LL FEEL LIKE A New MAN.

—STEPHEN LEACOCK. VANIIY FLAIR, JUNE 1914.

1915

Aprotean countenance and an almost herculean theatrical output made playwright George Bernard Shaw a V.F. fixture. So, too, his provocative political views as World War I entered its second year. "I'm for [Germany's Kaiser Wilhelm] in this war," said Shaw. "I have to be—everybody else is against him.... War isn't hell; it is getting space in the newspapers during war-time that's hell." Photograph by Malcolm Arbuthnot.

BURLESQUE, LIKE WORCESTERSHIRE SAUCE, IS A CONDIMENT, NOT A FLUID. TOO MUCH OF IT IS MORE THAN ENOUGH.

—P.G. WODEHOUSE, V.F., MAY 1915

1916

SOME DAY, WHEN FATE HAS DELAYED YOUR LAUNDRY, GO DOWN AND TAKE A TRY AT BEING A BOHEMIAN. HUNDREDS OF PEOPLE ARE.

— ROBERT C. BENCHLEY, V.F., MARCH 1916.

Comparing his form to those on Greek bas-reliefs, the magazine wrote of Vaslav Nijinsky, "No dancer of our day, male or female, has created quite the furore." And who better to render the white-hot star of the Ballets Russes (here, as the Golden Slave in Scheherazade) than Baron Adolph de Meyer, creator of the period's most luminescent portraits?

1917

Cameras at the time could require languorous exposures, creating lush light or shade. As a result, shadow play (and an occasional silhouette) became a V.F. signature, as in this nude ("Putting a Woman on a Pedestal") and this statuesque study of actress Inez Clough (below) for a story on New York's new "Negro Theatre." Photographs by Karl Struss (left) and Maurice Goldberg.

1918

Frolicking nudes and half-dad nymphs ('The vogue for outdoor dancing is rapidly spreading") filled page after page (February cover, left, by Warren Davis). But as the Great War raged, illustrators with increasing frequency pursued patriotic themes (bottom right). V.F.'s coverage of the conflict ran the gamut from poetry (Dorothy Parker, Gertrude Stein) to lithographs, from aerial photos to this shot of a battle-bound Yale football team [below). Edward Steichen (in a pre-war self-portrait, bottom left) was Vanity Fair's chief portraitist during the next decade. A painter by training, he would become one of photography's most influential champions and curators.

1919

THE OUTSTANDING FEATURE OF THE GREAT DRAMAS OF THIS SEASON IS THEIR THOROUGH LACK OF CHARM. YOU CAN COUNT THE EXCEPTIONS ON ONE HAND— AND HAVE THREE FINGERS LEFT OVER.

—DOROTHY PARKER, V.F., FEBRUARY 1919.

October 1919

CoNDE NAST Publisher

Price 35 cents

As this cover makes clear, Vanity Fair relished its position at some imaginary crossroads of the "smart set" (Vanity Fair Pi. and Fifth Ave.) even as it poked fun at the elite it wrote about. V.F. profiled newcomers Helen Hayes (at 18) and golfer Bobby Jones (at 17), trashed Dr. Thorstein Veblen's The Theory of the Leisure Class, heralded motorcars and Ziegfeld belles, Harry Houdini and Woodrow Wilson, and puzzled over jazz and telephone service, hashish and impending Prohibition—all as a prelude to the roaring, postwar 20s. October cover by John Held Jr.

1920

Celebrity" was a phenomenon born of two new forces: mass media and mass culture. Two celebrities V.F. helped mold into icons: Russian ballerina Anna Pavlova (above), adorned here as a sprightly bacchante, and John Barrymore, the "Great Profile," who made his Shakespearean debut as Richard III at Broadway's Plymouth Theater that year. Photographs by Franz Van Riel (above) and Baron Adolph de Meyer.

1921

Ralph Barton's group caricatures were V.I.P. jamborees, like this imaginary cruise (above) for lecturers and literary figures from the British Isles. The highbrow manifest contained poets William Butler Yeats (at second porthole from left) and Siegfried Sassoon (directly below that porthole), V.F. contributor G. K. Chesterton (foreground, presenting passport), and author Arnold Bennett (in profile, in front of far-right curtain). The magazine frequently showcased Barton and artists of all kinds, including Impressionist Claude Monet (left) at 80. Photograph by Baron Adolph de Meyer.

1922

Gertrude Stein—mother of experimental prose, drawing-room doyenne, and V.F. contributor—agreed to a Paris sitting for Man Ray, the Dada pioneer, Surrealist, and occasional V.F. photographer.

GENIUS, IN ART, CONSISTS IN KNOWING HOW FAR WE MAY GO TOO FAR.

—JEAN COCTEAU. V.F.. OCTOBER 1922.

1923

Subjects assumed fresh personae for the Vanity Fair lens. Consummate vaudevillian Fanny Brice (left) turned out in a tux. (Her granddaughter, Wendy Stark Morrissey, is currently V.F.'s Los Angeles editor.) Weighty dramatist Eugene O'Neill appeared almost serene at the Provincetown seashore (below, left). Boxer Jack Dempsey struck a Rodinesque pose. Photographs by Edward Steichen (left), Nickolas Muray (below, left), and Ira Hill.

THE SILENT MAN IN MOCHA BROWN SPRAWLS AT THE WINDOW-SILL AND GAPES; THE WAITER BRINGS IN ORANGES BANANAS FIGS AND HOTHOUSE GRAPES.

—T. S. ELIOT, V.F., JUNE 1923.

In one of the magazine's most enduring images, dance idol Isadora Duncan is ennobled by the vaulting grandeur of the Parthenon. Photograph by Edward Steichen.

IEES

Douglas Fairbanks mastered many roles: bon vivant of Broadway and Hollywood, studio owner, film producer, society host extraordinaire who entertained Hollywood's inner circle at Pickfair, the mansion he shared with his wife, Mary Pickford. He was even father to a sometime V.F. columnist, the actor Douglas Fairbanks Jr. This "candid" caricature purported to show Fairbanks senior "chatting in his own impressive French, to the small man in a homburg hat who stopped to shake his hand in front of Ciro's," the storied Los Angeles nightclub. Illustration by Miguel Covarrubias.

1925

Artists, actors, and photographers were encouraged to explore the fanciful. "Almost overnight, New York has become a city of towers,"said the magazine, which commissioned Hugh Ferriss to envision (below) how a new zoning law might bring "revolutionary changes in the city's aspect." To express their devotion to the stage, young marrieds Alfred Lunt and Lynn Fontanne adopted the inspired guises of Tragedy and Comedy. The pair would bathe in the footlights for 33 more years, leaving an almost regal legacy. Photograph by Edward Steichen.

EACH OF HER SIGHS WOKE HER DIAMONDS TO DARTING FIRES; BUT THE ROBBER DID NOT HESITATE.

-COLETTE, V.F., FEBRUARY 1925.

1926

When Rudolph Valentino died at 31, the magazine printed the last photo of "the Italian screen lever," noting that "many life-hungry women have literally been turned out of theatres in which [he] appeared on the screen." Like Valentino, comedy maestro Charlie Chaplin [below) often loomed larger than life. Photographs by Edward Steichen.

1927

Vanity Fair loved sophisticates [above), laved Harlem (celebrating an uptown revival meeting, left), loved pundits (praising critic and editor H. L. Mencken, below, as "commanderin-chief of militant public opinion ... wag[ing] war on smugness, intolerance, and hypocrisy"), loved dancers (including a bereted Fred Astaire, bottom left, with his early dancing partner, his older sister, Adele). Illustration by Miguel Covarrubias [left). Photographs by Edward Steichen [below) and James Abbe.

1928

The magazine brimmed with opinions, criticism, and gossip (Winchell on chorus girls, Sackville-West on society, Gide on art, Huxley on the sexes, Lippmann on Hoover); it was an apt era for "talkies" to emerge, and they earned their share of V.F. ink and imagery. Two stars of the new sound age: silent-film comedian Harold Lloyd (above, on a Coney Island set) and MGM's "First Lady of the Screen," Norma Shearer. Photographs by Edward Steichen.

1929

Old design ideals came crashing down just as Wall Street did. Deco reigned and Surrealism raged, MoMA opened and Rockefeller Center broke ground. And that fateful October, Vanity Fair underwent a clean, modernist face-lift. Eduardo Benito, who oversaw the redesign, exhibited a Deco penchant for geometric simplicity and bold color in his covers (August, below), here using a circle-cum-monocle to suggest an entire social class. December's number (bottom right) could be handily transformed, with a set of scissors, into a 3-D Santa.

The severe pageboy, the off camera gaze, the face off-center and looming in the frame. Everything about theTmage (above) felt modern—in keeping with the sensual, liberated Louise Brooks: free spirit, intellect, nightclub dancer, and transatlantic screen star. Composer George Gershwin's portrait (left) was as pithy as a classic lyric: profile theatrically chiseled in light, a trademark up-tempo perfecto, a curl of smoke suggesting a wisp of song. Photographs by Edward Steichen.

1930

Vanity Fair was enamored of the human form, reproducing Brancusi sculpture, nudes by Matisse and Picasso, and even woodcuts by Rockwell Kent (below). Nowhere was this more apparent than in portraits showing an athlete or actor qua specimen. Fittingly, Johnny Weissmuller (left) would soon be both—an Olympian turned thespian who would muscle his way onto the screen as Tarzan, the Ape Man.

And no issue seemed complete unless a dancer crossed its path: witness the already legendary Martha Graham (bottom), accompanied by Charles Weidman. Photographs by George Hoyningen-Huene (left) and Nickolas Muray.

1931

The era's most venerated heroes were portrayed, at times, in a spare, deferential style, as in Paolo Garretto's iconic caricature of India's Mahatma Gandhi (bottom middle) and Edward Steichen's depiction of aviation's avatar, Amelia Earhart (right).

Advances in four-color engraving, unique to Conde Nast's magazines, resulted in portraits such as this vivid Will Cotton pastel (above) of novelist (and V.F. essayist) Theodore Dreiser in full gloom, his brow as menacing as storm clouds.

The editors dubbed Cotton's caricatures "models of polite causticity." Of actor Clark Gable's likeness (below) they wrote: "Here the feminine reader may pause and cast an indulgent eye upon ... the nation's latest heart-snarer." Photographs by Edward Steichen.

1932

ALONE OF ALL THE CENTURIES, THE TWENTIETH SEEMS SO FAR TO HAVE PRODUCED NO [HISTORICAL] BEAUTY. THERE IS ONE POSSIBLE EXCEPTION. THERE IS GRETA GARBO.

—CLARE BOOTHE BROKAW, V.F., FEBRUARY 1932.

laywright, composer, and actor, Noel Coward was sophistication incarnate, as deliberate and alert as the cat statuette behind him. Even his cigarette smoke followed his shadow's lead. "Boston ingenue" Bette Davis, 24 (far left), and a cartoon Greta Garbo (above, left) conveyed a similar self-conscious elegance. But such world-weary airs seemed increasingly dissonant as the nation faced the deepening Depression and war's gathering rumor, evidenced by the cover at left. Photographs by Edward Steichen (above) and Horst P. Horst.

1933

The defining portrait was—and remains—a Vanity Fair hallmark, as in these studies of First Animator Walt Disney (left), New York Ranger defenseman Ching Johnson (below), and actor Paul Robeson as "the Emperor Jones" (bottom). Inventions such as flashbulbs, portable cameras, and wire-transmitted pictures spurred experimentation. In the early 30s, the magazine ran news photos, assigned Dr. Erich Salomon to cover Congress with his "candid" camera, and printed rich color by Anton Bruehl and collaborator Fernand Bourges. Actress Judith Wood (right) sampled New York's nocturnal club scene. Photographs by Edward Steichen (left and bottom), Anton Bruehl (below), and BruehlBourgos (right).

WHATEVER ELSE MAY BE SAID OF MAUfiU, THE PLACE WHERE THE„MOVIE QUEENS GROW THEIR SUNBURN, IT IS PROBABLY THE FINEST BEXCH EVER CREATED BY GOD.

—JAMES M. CAIN, V.F., AUGUST I9i

1934

If society's morals seemed adrift at times, the magazine was a virtual trade wind, lauding actor Gary Cooper (below, left), "whose long, lean, tautly modeled face represents... the epitome of cinema sex appeal," and Elsa Maxwell (below) "social arbiter deluxe," famous for her "licentiously madcap soirees." Praise be for august men of letters, such as prolific critic Alexander Woollcott (a V.F. columnist) and his pal and sometime collaborator, two-time Pulitzer Prizewinning playwright George S. Kaufman (near left). Photographs by Edward Steichen (left), George Hoyningen-Huene (below, left), and Cecil Beaton (below).

YOU MIGHT SET FIRE TO WIDOWS, DEFLOWER ORPHANS, OR FILCH E FLAGS FROM SOLDIE* GRAVES, AND STILL BE INVITED TO ALL TP LITERARY TEAS.

—DOROTHY PARKER, V.F., FEBRUARY

'Can there be something to this business of the West declining?" Vanity Fair asked of Mae West's "gaudiest and bawdiest" movie, Belle of the Nineties. Captured on set, at ringside, the actress set eyes on a prized fighter in what the editors called a "saga of gay life in old New Orleans." Photograph by George Hoyningen-Huene.

1935

A simple prop could make an image an icon. Something horizontal yet ursine suited starlet Jean Harlow (right). An upright and a muse served Moss Hart and Cole Porter (below, left), librettist and lyricist, respectively, for Broadway's Jubilee. Bright running shorts against a bare frame gave a classic bearing to Jesse Owens (below, right), America's bright hope for Adolf Hitler's 1936 Berlin Olympics. Photographs by George Hurrell (right) and Lusha Nelson (bottom left and right}.

IT TAKES ABOUT AN HOUR TO SET UP THE GUILLOTINE. EACH PIECE IS NUMBERED, AND THE WHOLE IS SO PERFECT, MECHANICALLY, THAT IT CAN BE ASSEMBLED IN COMPLETE SILENCE.

—JANET FLANNER, V.F., MAY 1935.

ndustry informed the aesthetic of the age. As photographers shot for big business, advertisers, and magazines, a sense of grand scale, mechanized order, and sometimes graphic formality entered their work. This was true in portraiture as well, apparent in this representation of Igor Sikorsky, creator of the Pan American Clipper— and, in time, the helicopter. Photograph by Lusha Nelson.

1936

JOAN [CRAWFORD] TELEPHONES FROM THE SET AND REMINDS HER COOK OF A DISH WHICH SHE KNOWS TO BE A FAVORITE WITH HELEN HAYES.

—MARGARET CASE HARRIMAN, V.F., FEBRUARY 1936.

The decade's events began bearing down on the publication. Gone were the top hats and tuxes that had dominated 17 covers throughout the late 20s. By 1936, swastikas or Hitler's visage had appeared on 7 covers; F.D.R., Uncle Sam, or American flags on 22. The February edition (right) bore an alluring facade (Bali Beauty, by Miguel Covarrubias) and profiled Broadway's Dead End gang (above, by Anton Bruehl), who played streetwise kids toughing out the Depression. It would be the last issue of Vanity Fair, Incarnation I. "Vanity Fair," wrote social historian Cleveland Amory a generation later, "was as accurate a social barometer of its time as exists. There never was, nor in all probability ever will be again, a magazine like her."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now