Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowAt the Lennon privacy trial, the author finds Yoko Ono very different from her image, while Michael Skakel's sentence raises new questions, and Lily Safra appears in a taped re-enactment of the night her husband died. As for New York society, a Minnesota prison is the latest private-jet destination

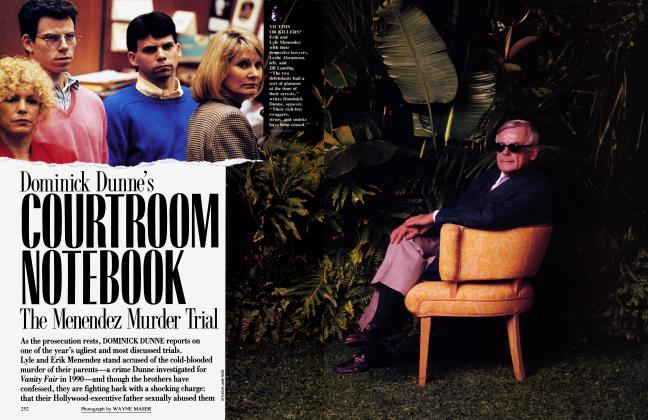

December 2002 Dominick Dunne Stephen DanelianAt the Lennon privacy trial, the author finds Yoko Ono very different from her image, while Michael Skakel's sentence raises new questions, and Lily Safra appears in a taped re-enactment of the night her husband died. As for New York society, a Minnesota prison is the latest private-jet destination

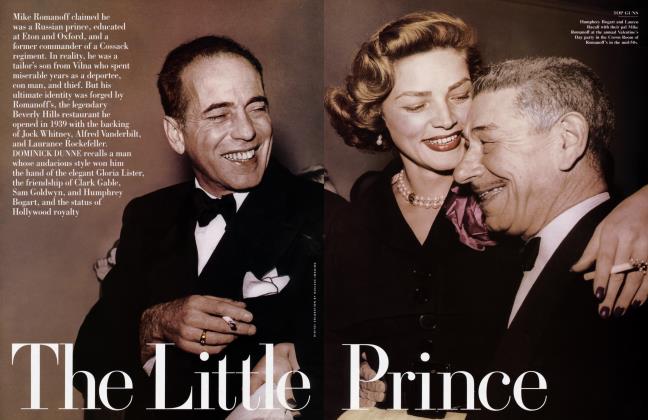

December 2002 Dominick Dunne Stephen DanelianOne of my favorite possessions is an 8-by-10 glossy, taken back in the 60s, of my three kids being introduced to the Beatles at a Beverly Hills garden party outside the beautiful house of Alan Livingstone, the president of Capitol Records, then the Beatles' recording company. My daughter, about three at the time, is curtsying to Paul McCartney, to his delight. One of my sons is beaming just to be in the presence of John Lennon, whom he worshiped. Years later, that same son was standing in the crowd at the candlelight vigil outside the Dakota apartment building in New York the night after Lennon was murdered. So I've always loved the Beatles, but I could never stand Yoko Ono, and it wasn't because she was alleged to have broken up the group. I never liked her music, and I never liked her art. Watching her from afar, at the occasional New York function, I found her to be perpetually disagreeable. It seemed to me as if there was never a moment of joy in her life and she wanted to keep it that way.

I was quite unprepared, therefore, when I arrived at the courthouse on Pearl Street in downtown New York, where her case against a former personal assistant named Frederic Seaman was being tried, to change my opinion of her completely. It turned out that the former personal assistant was a swine who had stolen family photographs of the Lennons, as well as letters, diaries, and notes written by Lennon, and sold them, despite having signed a confidentiality agreement. The crime was hardly original. People hired by the famous often renege on confidentiality oaths and sell stories of what they have witnessed on the job, but after 22 years Seaman's perfidy had finally reached its limit, and Yoko Ono was out to put a stop to having her life, her son's life, and her late husband's memory be the main source of this man's income.

Mrs. Lennon, as she preferred to be called, turned out to be not a bit like the image I had of her. She was extremely pleasant, friendly, chatty, dishy even, and funny, on occasion. Her pride and joy is obviously her son, Sean, who has been famous from the day of his birth just because he is the son of John Lennon and Yoko Ono. Once, I overheard their conversation about the best way to get out of the courthouse without being photographed. Sean told his mother, "If you go out the back way, they'll have a camera there from now on. It's better to go out the front door, let them take our picture, and get in the car and go." I sat right behind Sean in the courtroom and talked a lot with him during the trial. He's 27. One of the schools he attended as a boy was the exclusive Le Rosey in Switzerland. His girlfriend is Bijou Phillips, a young beauty who is often written up in the gossip columns. I told Sean that Bijou's father, the late John Phillips of the Mamas and the Papas, was a friend of mine back in the 60s, and that on occasion I had gotten stoned with him. There is not an iota of brattiness in this young man. He became great pals with the sketch artists, and soon was drawing the witnesses so well that some of his sketches were published in the New York Post's accounts of the trial.

Ono didn't win any money, but money was never the issue.

The thing that got me the most, and practically turned me into a ko junkie, was the showing of some video footage Seaman had removed from the Lennons' home. He had taken the video on the Lennons' camera. "Weren't you friends with Mr. Seaman?," Glenn Wolther, Seaman's lawyer, asked Yoko Ono. "You're mixing up friendly and friends," she replied. "I was friendly with him, and I trusted him as an employee, but he was an employee." The video had been shot at a small lunch party at the Lennons' Long Island house in Cold Spring Harbor in 1980, shortly before Lennon was murdered. The lunch table was set up on the beach, and people were very casually dressed. Sean was four years old, as cute a kid as you'll ever see, and, obviously, the apple of his father's eye, judging by all the hugs and kisses and the sheer joy on John Lennon's face. At one point Yoko holds Sean and they roll over and over in the sand, both laughing uncontrollably. The black-and-white video provided a wonderful picture of a famous family loving one another. Sean, who had never seen the film, said something like—I couldn't write it down right in front of him during such an emotional moment—"I didn't know my father kissed me and loved me so much." Mrs. Lennon, with her excellent lawyer, Paul LiCalsi, won the case, and everyone in the courtroom was happy for her. Seaman is prohibited from ever again making use of the materials. Mrs. Lennon didn't win any money, but money was never the issue: she doesn't need it, and Seaman doesn't have any.

A date has finally been set for the trial of Ted Maher in Monte Carlo. As of this moment, it is scheduled to begin on November 21. Just shy of three years after the deaths by asphyxiation of Edmond Safra and Filipino-American nurse Vivian Torrente, Maher, the American male nurse who is being held responsible for their deaths, will finally appear in a courtroom. As I said in my last diary, the husband of Vivian Torrente allegedly received a payoff, and a recently translated autopsy report indicates that Safra's DNA was found under Torrente's fingernails and Torrente's DNA under Safra's fingernails, and that there were suspicious marks on Torrente's neck and body. That bit of information might suggest that Vivian Torrente attempted to get out of the bathroom in which they were trapped and Safra stopped her, but we'll probably never know. I recently watched twice—on two different nights—a video that was laughably referred to as a re-enactment of the events of the night of the tragedy. It had been commissioned nearly two years ago by Judge Patricia Richet, who is no longer on the case. All the principal figures, including Lily Safra and Ted Maher, were brought together at the scene of the tragic events at the same time of night that the deaths occurred. The object was to have them walk through what had happened that night. But the film does not deliver an accurate picture. There is nothing in it, for example, about the police holding back the firemen for nearly an hour, during which time Safra and Torrente might have been saved. Nor is there any reference to a Safra guard finally arriving at the fire with a key to the locked bathroom and being put in handcuffs by the police. It will be interesting to see if the roles of the firemen and the police are introduced into the trial.

The re-enactment must have cost a great deal, but it is obvious that very little thought was given to the quality of the filmmaking or the soundtrack. It looks as if they just handed the camera to a policeman, or someone else standing there, who had no technical knowledge of how to make a film. There are endless shots of Judge Richet giving notes to a secretary and opening and closing doors. Everyone speaks in French, which is to be expected, but no one ever says, even in French, "This is the drawing room," or "This is the nurses' station," so it is difficult to know where you are most of the time— and I had a French translator at my side the second time I ran the nearly three-hour video. There are a lot of lawyers on the scene, including Marc Bonnant, one of Lily Safra's lawyers, who canceled two interviews she had called me to set up shortly after the death of her husband. Several times Lily Safra can be seen in the background, always in the company of a lawyer. She looks quite classy, in black trousers and a black top, and she neither overplays nor underplays her grief. She appears to be gracious to everyone who approaches her. There is something gallant about her walking through the apartment for the first time since the fire, seeing the burned wreckage of her former home, where her husband had died a terrible death. However, we never see the room where she was sleeping at the time of the fire, located at the other end of the penthouse from Safra's room.

People walk right in front of the camera, and sometimes stand in front of it, blocking shots completely, and the cameraman apparently didn't have the clout to tell them to move out of the way. But at least the viewer is given a walk through the famous penthouse. All the furniture has been removed. The rooms that were damaged were terribly burned. What you see are the remains of an overly decorated apartment: in the entry, for example, are mirrored walls covered by a peach-colored treillage, faux Fragonard murals, and stylized swans painted on the elevator doors. The bathroom where the two bodies were found was the least burned. It is beautifully paneled, with a leopard-print rug on the floor. The film's one clear shot is of Safra's toilet, with handrails to aid the invalid in sitting down and standing up. One of Maher's jobs was to carry him there.

Finally we see Ted Maher. His restraints have been removed. This is the first time I have seen Maher since I started writing about him, nearly three years ago. He is dressed in a double-breasted brown suit, with a white shirt and brown tie. He speaks in English, and a translator tells the judge what he is saying. My translator told me that one of the lawyers says to the judge, "We would like him to stand where he was, to take the position he was in. Do exactly what [he did] then." When Maher talks, his face is often in complete darkness, even though a single step to the left would have put him in the light. A lawyer for the Safra brothers, Georges Keijman, speaks quite harshly to him. There are moments when Maher seems very confused. At one point you can distinctly hear him say, "I can't believe what pushed me to do this." Many letters had been written to the judge by the Skakel family and their friends asking for leniency. One from Ethel Skakel Kennedy read in part, "It pains me that others miss his sweetness, kindness, good cheer . . . and love of life; his perceptiveness, exuberance, and extraordinary generosity." Those were kind words, considering that Michael, in a book proposal that became widely circulated before he was indicted for the murder, had been very hard on his aunt in the matter of her son David's death. Mickey Sherman, Skakel's lawyer, went on so long that reporters stopped taking notes. He read a four-page single-spaced letter from Michael's cousin Robert Kennedy Jr., in which Kennedy described Michael as a combination of John Candy, John Belushi, and Curly of the Three Stooges. The letter had been written to the judge, and the judge had undoubtedly read it, but Mickey was not playing to the judge. He was playing to the audience behind him, as if the name Kennedy still evoked the dazzle it once had. As is usual with petitions written to judges requesting leniency, there was a sameness to many of the letters, which all attested to Michael Skakel's long sobriety and good works. It made the letters sound as if they had been requested rather than offered.

At moments on the video, Ted Maher seems very confused.

This next piece of news may sound a bit stale, because my diary didn't appear in last month's Music Issue, but I can't let the sentencing of Michael Skakel by Judge John Kavanewsky to a term of 20 years to life pass without comment. The air in the courtroom in Norwalk, Connecticut, on August 29 was fraught with tension. Not all of the Skakel family came to hear the bad news. Tommy Skakel, the longtime suspect, stayed away. So did Michael's first cousin James Dowdle, who was called James Terrien at the time of the murder; Michael Skakel had always claimed he had gone to watch Monty Python on television at the Terrien house that night, but years later he suddenly gave a different story to the private investigators hired by his father to take suspicion off the Skakel family. When Michael entered the courtroom, without handcuffs but wearing shackles, his supporters rose as a body. Someone called out, "We're with you, Michael!"

Jonathan Benedict, the prosecutor, had this rejoinder: "Yes, he was only 15 when he committed this crime, but where's he been in the meantime? Skiing, golfing, going to college, occasionally working, getting married, getting divorced. Most importantly, hiding—if not from the inevitable, certainly from the reality."

The drama didn't really start until Dorthy Moxley, standing in front of the bench, gave her victim's impact statement directly to the judge; she spoke lovingly of her daughter and asked the judge for the maximum sentence. It's no secret that I am an enormous admirer of Mrs. Moxley's, and I was moved by the way she spoke about Martha. She said that if the Skakels had dealt with the situation at the time, instead of covering it up, all those years would not have been wasted. At that point Julie Skakel, Michael's sister, got up and stormed out of the courtroom. Maybe this was just a trip to the ladies' room, but there was anger in her stride. Then John Moxley, Martha's brother, gave his victim's impact statement. He talked about how Martha's murder had been a factor in their father's early death. As he walked back to his seat, after having asked for the maximum sentence, the convent-educated Ann Skakel McCooey said to him, "You son of a bitch." McCooey, standing in as family matriarch for her more famous sister, Ethel, who it had been rumored would attend but did not, had been outspoken throughout the trial. She once called me a jerk in a loud voice. The family arrogance of acting important when they aren't important anymore persisted even as one of their own was being sent to prison for 20 years.

Then it was Michael Skakel's turn—the first time he had spoken in the courtroom, because he had not taken the stand. People have asked me if I felt sorry for him, and I have said yes, but in a qualified manner. I've always considered self-pity one of the least attractive of traits, and he wallowed in it. It would not be possible to make a worse impression than Skakel made when he finally addressed the court. He cried until tears flew in all directions. He lashed out at others. He even got in a few mean cracks about his wife, Margo Sheridan Skakel, who had divorced him before the trial began. He said his three-year-old son had told him his wife hated him. He even likened himself to Jesus in his suffering. It was embarrassing and undignified, but I couldn't stop looking at him. It was like watching a train wreck, and, yes, I did feel sorry for him, although I couldn't help thinking, What a wonderful scene this is going to be for some actor to play when a movie of this story is made.

Taubman is one of the most popular figures in the prison.

Jonathan Benedict, whose excellent work at the trial I have praised to the rafters, has, since his well-earned victory, revealed a resentful streak toward certain reporters, including me. I heard him slough me off in a dismissive manner in his post-conviction interview, and I chose to ignore it, but a person close to him told me he was sorry that Benedict felt that way, especially toward those of us who had worked long and hard keeping alive a story that seemed destined for oblivion. I include Len Levitt of Newsday; Tim Dumas, who wrote the book Greentown and has been a constant presence on television chat shows, discussing the case; Mark Fuhrman, whom I brought to the case after I had come into possession of the Sutton report and who wrote the best-selling book Murder in Greenwich, for which I wrote the foreword. I must not leave out my own efforts, either. My 1993 novel, A Season in Purgatory, put the spotlight back on the long-dormant case, as did the miniseries that followed, and I have referred to the case over and over in Vanity Fair in order to keep the story in the public eye. So, Mr. Benedict, if it weren't for us—whom Dorthy Moxley calls her angels—you wouldn't have had the case of your career in which to shine so brilliantly.

In his remarks to the media after Michael Skakel was convicted on June 7, Benedict suggested that Skakel must have had help after the murder. I've recently heard, through a fortuitous meeting in the dining room of a Maine resort hotel, that four accomplices reportedly helped move Martha Moxley's body and clean up after the murder. I was given the four names by a well-connected source, along with some alarming information that has never been made public. During the course of the trial, all four of the alleged accomplices had been in the courtroom, though not all at the same time, and they always kept their distance from one another. The name of only one of the four surprised me. That person, I was told, had been responsible for getting rid of the missing part of the golf club that had been the murder weapon. My informant told me that it took four people to move Martha's body. He also said that a prominent forensic scientist had deduced that the tallest of the four had carried Martha's head. He told me the bloody clothes they had been wearing were bleached again and again during the night. When I was writing about the case in A Season in Purgatory, I talked to a handyman, now dead, who lived in a room under the back stairs in the Skakel mansion. In those days, grand houses had back stairs, mostly for servants to use. He told me that people were running up and down those stairs all that night, and I used that in the novel. Should Michael Skakel's guilty verdict be overthrown during the appeal process, these names might be of great value to the prosecution.

It has become quite the thing for New York's private-jet set to fly out to Rochester, Minnesota, to visit the immensely rich Alfred Taubman, former C.E.O. of Sotheby's, who is incarcerated at the Federal Medical Center for a year and a day after having been found guilty of collusion in the highly publicized Sotheby's-Christie's auction-house scandal. I covered his trial in this magazine, and I am going to devote an upcoming episode of my TV series, Power, Prejudice, and Justice, to it. It's now frequently part of dinner-table conversation, in certain circles, for someone to say, "I'm flying out to Rochester on Saturday to see Alfred." It is in keeping with Taubman's character that, according to all accounts, he is making the best of things. The reports I get are all positive. With good behavior, he may be out in ten and a half months. I was told by one of his visitors that he was in a room—not a cell—which he shared for a while with a drug dealer. He has lost 16 pounds, and the Mayo Clinic is practically next door. He reads The Wall Street Journal and The New York Times daily. He has started a bridge club and is one of the most popular figures in the prison. Visitors are stripped of all possessions except for a driver's license and $20 in quarters for the vending machines. Taubman is the oldest inmate, and he's taking his medicine without complaining. There's something admirable about that. In many ways, the junk-bond king Michael Milken's life was enhanced by his prison experience. That's what I see happening to Alfred Taubman.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now