Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowEven as Michael Skakel's siblings beg for money to finance an appeal, the author helps corner an accused Palm Beach murderer with his Court TV debut, then retraces his steps on the Chandra Levy case, weekends in ImClone-scandalized Southampton, and honors Nancy Reagan at the White House

September 2002 Dominick Dunne François DischingerEven as Michael Skakel's siblings beg for money to finance an appeal, the author helps corner an accused Palm Beach murderer with his Court TV debut, then retraces his steps on the Chandra Levy case, weekends in ImClone-scandalized Southampton, and honors Nancy Reagan at the White House

September 2002 Dominick Dunne François DischingerAs I write this, we're in the sitting-out stage of the Skakel-Moxley story, waiting for the day of sentencing and the appeals that are already being prepared. There have been a few interesting developments. The sentencing date has been postponed three weeks, and Mickey Sherman, while he hasn't exactly been replaced as Michael Skakel's lead attorney, has definitely been backseated since the guilty verdict came down on June 7. The verdict stunned Sherman completely; it apparently never occurred to him that he would not win. Afterward, I happen to know, Sherman arranged for Julie Skakel and two of her brothers, Stephen and David, to appear on 20/20 for an interview with Barbara Walters, as a prelude to the appeal process. Walters flew home from a weekend party at Chatsworth, the grand country house of the Duke and Duchess of Devonshire in England, only to find that the interview had been canceled. Whoever is calling the shots for the Skakel family these days has hired two lawyers from Hartford, Hope Seeley and Hubert Santos, to handle the appeal. Seeley was co-counsel for Alex Kelly, the Darien, Connecticut, high-school rapist who hid out in Europe for eight years, supported by his parents, until he voluntarily returned to this country and was tried and found guilty. Seeley would not tell Lindsey Faber of Greenwich Time if it was she who had canceled the interview with Barbara Walters. Sherman was quoted in Faber's article as saying, "We're all on the same team here, but I'm not leading the appeals. I'm like the general manager now, I guess you could say." He was the substitute host for one show of The Abrams Report on MSNBC when Dan Abrams was on vacation, but he did not discuss the Skakel trial. Meanwhile, his client Michael Skakel remains at the Garner Correctional Institution in Newtown, Connecticut.

Having observed the very rich Skakels from afar for many years, I'm astonished that their great fortune, which was once said to exceed that of the Kennedys, seems to have evaporated. Or perhaps someone in the family just doesn't want to cough up any more money for Michael's defense. How else can you explain why Michael Skakel's youngest brother, Stephen, who was a very young boy at the time of the murder—too young to go with the rest of the family to the Belle Haven Club for drinks and dinner and more drinks that terrible night—has sent out a private letter to sympathetic friends asking for money to finance the appeal? The letter, which was anonymously turned over to the Associated Press by one of the recipients, is rather embarrassing to read. "Michael's financial resources for appeal are nonexistent at this time," Stephen writes, and he asks people to make checks out to the Never Give Up Fund and send them to the home of Julie Skakel in Darien, Connecticut. Julie is the second-oldest of the seven Skakel children, and the only girl. The letter also requests that people send letters to Judge John Kavanewsky Jr. asking for leniency, and gives suggestions for ways to phrase it, such as "He helped me get sober." Stephen advises, "Do not say anything negative about the judge or the system."

"Michaels resources for appeal are nonexistent," his brother writes.

I don't think the guilty verdict will be overturned. Should it be, however, I believe that the second trial will be more encompassing than the first, and will possibly involve Michael's brother Tommy, who was the chief suspect for many years but who was never called to the stand by either side. Prosecutor Jonathan Benedict was clearly sending out some kind of message when he said to reporters after the verdict, "Someone had to have helped Michael clean up. There was a lot of blood."

In writing about the rich and powerful in criminal situations, I've noticed that wealthy people with knowledge of a given crime don't like to come forward with their information for fear of being cross-examined on the stand by an unfriendly defense attorney who might pry secrets out of them, as well as for fear of having their names and pictures in the papers and on the nightly news. Since the Skakel verdict, I've learned a lot of things that didn't come up at the trial. One guy who says he was part of the rich-kid group that grew up around the Skakels wrote me, "Tommy and Michael used to mimic Johnny Carson and Ed McMahon's habit of swinging imaginary golf clubs and then laugh. They joked about Martha Moxley's death." Another guy wrote me about how he had nearly had his eye gouged out by Michael during a schoolyard fight when they were both in the seventh grade at the Brunswick Country Day School in Greenwich. "Michael put his thumb over my right eye and started pressing. . . It's hard to describe the frenzied intensity he had. But I had the unmistakable sense that he was enjoying himself. There was pleasure for him in inflicting the pain." One new piece of information came to me from an unimpeachable source: a pair of laundered pants belonging to Michael that was found in the Skakel trash after the murder was later discovered missing from the evidence room at the Greenwich Police Station. I'd like to get to the bottom of that story.

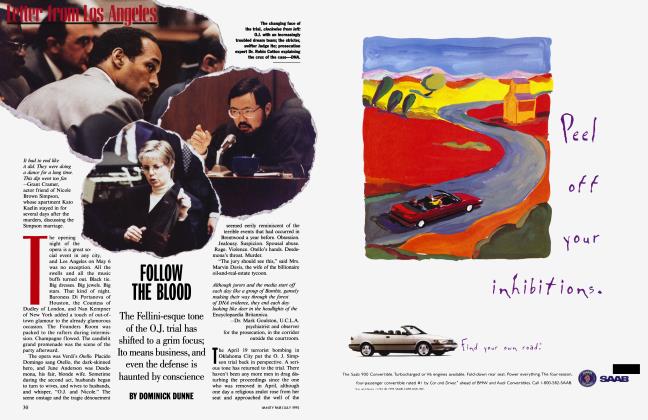

I'm the host of a new series on Court TV called Power, Privilege and Justice. I started my career in television in the early 50s, as the stage manager of The Howdy Doody Show, and now I'm back, acting as if my name were Alistair Hitchcock. The first show was about a semi-rich Palm Beach heel named James Sullivan, who had been on the lam for 15 years, after having been accused of hiring hit men to shoot his African-American wife, Lita—who was an impediment to his social climbing—on the day she was to go to court, sue him for divorce, and demand alimony payments that would have stunted his fancy lifestyle. Two weeks after the show aired, Sullivan was found and arrested in Thailand, where he was living in a condominium outside Bangkok with his girlfriend. John Walsh of America's Most Wanted is claiming credit, and he has indeed been reporting on the Sullivan case for years, but no one will convince me that my show, which aired just two weeks before the bust, didn't play a part in tracking the louse down. Sullivan told a reporter in Thailand that he wants to return to the United States and prove his innocence.

This month I paid my first visit to the White House. I don’t care how sophisticated you are, or the how many swell places you've been to, attending a private ceremony in the White House is an awesome experience. It has nothing to do with which political party you belong to; it's about being a proud American. Nancy Reagan has been a friend of mine for about 45 years, going back to when she was an actress, quite a few years before Ronald Reagan became governor of California. She and a small, distinguished group were receiving the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the highest civilian award our government can give, from George W. Bush. It was thrilling to be in that beautiful house, where the Marine Band, in splendid red uniforms, played as we walked through the marble halls looking at portraits of our country's presidents. I talked to Colin Powell and his wife, Alma, and to Condoleezza Rice. I shook hands with the president, and Laura Bush, looking wonderful in a lavender dress, stopped to talk with me. Nancy Reagan had spent the night before in the Lincoln Bedroom, and had had dinner with the president and First Lady—just the three of them. She told me that all the old staff from her time who were still on duty came by to see her. "So many hugs," she said.

The one thing that bothered me was the realization that I could have gotten into the White House with a bomb or a gun in my pocket. I arrived in a chauffeur-driven car with Mrs. Abraham Ribicoff, the widow of the senator, and Peter Brown, whose New York public-relations firm's clients include Prince Charles and Andrew Lloyd Weber. We were all guests of Nancy Reagan's. After entering the grounds of the mansion, we were stopped twice by security men with guest lists. We all had photo identification and a card that had come with the invitation to present at the door of the White House. The guest lists the guards had were just loose sheets of paper, not even on a clipboard, and the names did not appear to be in alphabetical order. Neither guard could find Casey Ribicoff's name, and they didn't even ask Peter Brown or me who we were. They just waved us through. By contrast, we were given a full security search at Reagan National Airport, where we later went to get the shuttle back to New York: shoes, feet, bags, body—the works. Frankly, I could have done with a little less of that thoroughness at the airport and a little more of it at the White House.

Two weeks after my show, James Sullivan was arrested in Thailand.

The Fourth of July weekend is the one time each summer that I spend in the fabled Hamptons, opting for the quiet life of the Connecticut countryside the rest of the season. But Southampton was fun—lunches, dinners, beach clubs, white trousers, blue blazers, Gucci loafers, no socks. Hi, darling, kiss, kiss. No, I'm not going to Lally's, but I'll see you at Felix and Liz's. Just a year ago, Sam Waksal, of ImClone fame, was the hottest weekend guest out there, appearing at all the right parties, being besieged in the way the new rich often are. Waksal was much talked about this year, too, but in a very different way. His company's down the toilet, and so's he. He'll never again be in the position of importance he held so briefly last summer. He's also done great damage to my friends Martha Stewart and Peter Bacanovic, Stewart's broker. The other headliner of last year's Fourth of July weekend was Lizzie Grubman, who backed up her father's S.U.V. into 16 people. She was just lucky that she didn't kill one of them. I sensed a real resentment that a year has gone by and there is still no date for Grubman's trial. The feeling is that important people are trying to work out a plea bargain for her, and that there will be a universal outcry from both locals and summer folk if she gets special handling.

On July 5, I spoke at Fridays at Five, a lecture series arranged by the Hampton Library in Bridgehampton. It's a wonderfully handled event, in a pretty outdoor setting with white folding chairs, and it draws a large audience eager to buy the guest writer's books. I talked primarily about the Skakel case. During the question-and-answer period after my talk, a young woman kneeling on the grass asked me when I had shifted my suspicion from Tommy Skakel to Michael Skakel. Later, as I was signing books, she came up behind the table where I was sitting and put her hand in the pocket of my blazer. I looked up at her, and she said, "I know everything about that night. I know what happened." She said she had put her telephone number in my pocket. I said, "How do you know?" She said, "I am Robert Kennedy's daughter." said, "Which one?" She said, "Call that number and I'll tell you." The area code was in another state. I waited until I was back in New York to call her. The message said she had lent her phone for the weekend to someone named Kimberley. I left my name and New York number. She returned my call when I was not at home, using a name that did not fit any of Robert Kennedy's daughters, and told my machine that she had decided to stay in East Hampton and would call me the following week. So far, nothing.

Because of space, I wasn't able last month to mention Liza Minnelli's dazzling comeback engagement at the Beacon Theater on Broadway. There she was, in all her glitter and glamour, putting on show that did her proud, produced by her new husband, David Gest. There's been a lot of dish in showbiz circles about their marriage, but the fact is they turned up in each other's life at just the right time. She needed him to get back her confidence and deal with her problems, and he needed her to exalt himself. Watching them together is fascinating. On opening night, Gest sat in the center seat of the first row. For every second of Liza's performance, with his eyes, behind dark glasses, riveted upon her, never veering, he was like Svengali, willing her to the greatness she is still able to achieve. And she did. She had the audience on its feet, yelling out her name. There were moments when she looked exactly like her mother, Judy Garland, when I heard her sing at her great Carnegie Hall comeback concert in 1961. At one point I looked behind me, and there was Broadway's Chita Rivera, all in sparkling white, with tears streaming down her cheeks.

I am still haunted by the murder of Chandra Levy, and I have doubts that it will ever be solved. An acquaintance of mine, who has been involved in the case from the very beginning, told me that he did not believe Chandra was killed in Rock Creek Park, where her remains were discovered a year later. I had a theory at the time of her disappearance—which I wrote about in my diary and voiced on Larry King Live—that she had gone off on the back of a motorcycle, possibly driven by a member of a motorcycle gang. A strange thing happened to me after that. Last fall a famous horse trainer telephoned me from Hamburg, Germany, to say that he had just been in the Middle East, where he acts as an animal behaviorist for many rich sheikhs and sultans who keep racehorses and polo ponies. His major employer, he said, has one of the largest racing stables in the world. My caller said that he had been an inspiration for the book The Horse Whisperer, by Nicholas Evans, and the movie made from it. He said that the romantic part of the story was not about him, but that the experience Robert Redford had with the wounded horse had been based on an actual experience of his. (Nicholas Evans's agent, Caradoc King, prevented me from verifying this point with Evans.)

The horse trainer told me that he was from Salinas, California, that his family had been friends of the author John Steinbeck's, and that the director Elia Kazan had used him to teach the late James Dean to act like a Salinas boy during the filming in 1954 of Steinbeck's East of Eden. I found all of this interesting, but I didn't understand what it had to do with me. Then he explained. At a party in Dubai, he said, he had met a famous procurer, who provided women for the nocturnal pleasures of important men in the Middle East and in the Middle Eastern embassies in Washington. The procurer, an upper-class Arab who spoke five languages and wore English tailored suits, asked the horse whisperer if he knew Dominick Dunne, and told him I was writing a book on the Chandra Levy case, which I was not. The horse whisperer did not know me, but he tracked me down through my literary agent, Owen Laster, at the William Morris Agency in New York. Although he had sought me out, he made a big deal of acting as though he didn't know who I was, other than a writer, and made it clear that he had never read me. I'd never read him either, but he has several books to his credit on animal behavior, which include pictures of him having tea with the Queen of England. He told me that the procurer had seen me present my motorcycle theory about Chandra Levy's disappearance on Larry King Live and that he even had a videotape of it. He told me three times that the procurer had laughed at my motorcycle theory and called it absurd. I remember thinking that it wasn't necessary to tell me that three times, but I didn't say anything. Then he told me that the procurer had been in Washington on the day Chandra disappeared, and had seen her in a drugged state being put on a Middle Eastern plane by five men, one in front of her, one behind, one on each side, and another leading the way. He told me the procurer had said to him, "Let me put it this way. She wasn't walking." The horse whisperer suggested to me that Chandra Levy had been dropped into the ocean.

Naturally, I found this information distressing and wondered why I was the recipient of it. I didn't realize then—so caught up was I in the intrigue—that I was possibly being set up. I did the proper thing with such information; I went to Washington and talked with people investigating the case. At their request I went to England, where they hooked me up with M.I.6, British foreign intelligence. Their thought was that the procurer would be at the Dubai Stakes race in Newmarket on October 20 and would recognize me from the Larry King tape. But nothing came of it. In England, I had unpleasant words over the telephone with the horse whisperer when he claimed not to know the name of the procurer, and then I never heard from him again. The trip was a bust. The people I had met with in Washington had no further use for me. Months passed. Then, this past May, Chandra Levy's skeleton was found in Rock Creek Park. She hadn't been dumped into the sea, and now I'm beginning to wonder if my original motorcycle theory wasn't right after all, and if I wasn't being hoodwinked into abandoning it. Perhaps the horse trainer was also being hoodwinked in his role as messenger. I still have no idea who was behind it. In that last phone conversation, the horse whisperer grew very agitated with me and said that he did not wish to discuss the matter any further.

I was fortunate enough to know the legendary Lew Wasserman for decades, but I didn't actually become friends with him until after I left Hollywood and the movie industry and returned there from New York to cover the murder trials of the Menendez brothers and O. J. Simpson. That's when I started having dinner with him and his formidable, wonderful wife, Edie, either at Dan Tana's restaurant on Santa Monica Boulevard or at Drai's on La Cienega—it's now located in Las Vegas. Lew was one of the great historians of Hollywood. He spoke in a very low voice, but it was worth the ear strain to hear his stories of the early days of the industry, when he and Jules Stein had played such large parts as founders and agents at MCA. He remembered all the details, but he never wrote them down for future historians. Almost invariably joining us was the Wassermans' great friend the irrepressible actress Suzanne Pleshette, one of the funniest women in Hollywood, who is never averse to using the occasional four-letter word to make her point and who always kept the normally taciturn Lew in stitches.

He died on June 3, and in July I attended his memorial service at the Universal Amphitheater on the movie lot he loved so much. He once took me all through the studio—soundstages, back lot, theme park, and a variety of restaurants. Edie and the chauffeur stayed in the car. It had all been his dream, and he had seen it come to fruition. He was like a chieftain modestly showing off his fiefdom, and his eyes still possessed the visionary look of things to come, but his time was up at Universal. New people had come in and taken over. However, all over the lot that day, every guard, every propman, every gaffer, every actor who passed him tipped his hat or waved a greeting at the great man.

Bill Clinton, the former Arkansas governor whom Wasserman helped to become president of the United States, gave one of the eulogies. In the roped-off section Linda Bird Johnson Robb, the daughter of President Lyndon Johnson, sat in front of me, holding a chair for her sister, Luci Baines Johnson Turpin. Former First Lady Nancy Reagan was there, as were former vice president Al Gore and House minority leader Richard A. Gephardt, and Los Angeles mayor James K. Hahn, and Warren Beatty, and Jodie Foster, and Sharon Stone, and Kirk Douglas, and on and on. In the first three rows sat all the major power figures of Hollywood—Steven Spielberg, Jeffrey Katzenberg, David Geffen, Barry Diller, Brian Grazer, Ron Howard, Ron Meyer, one after the other of them, there to pay their respects to the last great Hollywood mogul. There's not a person in Hollywood today who would get a send-off like that.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now