Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

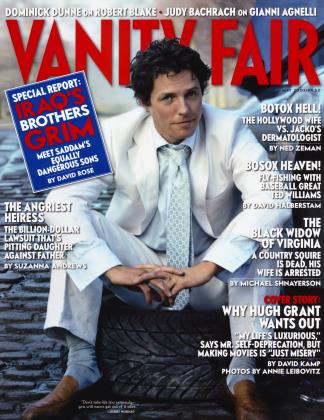

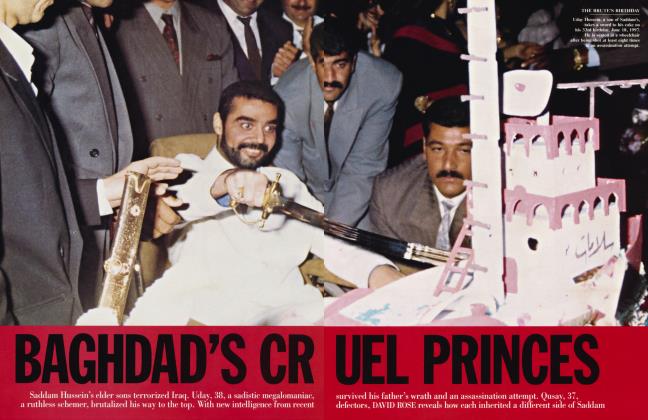

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowBaseball great Ted Williams brought the same passion to fishing as to hitting, and for six decades he hit, fished, and argued with a man who understood (and forgave) his dark side, Boston teammate Bobby Doerr. With this excerpt from his new book, The Teammates, the author explores a glorious friendship in two sports.

May 2003 David HalberstamBaseball great Ted Williams brought the same passion to fishing as to hitting, and for six decades he hit, fished, and argued with a man who understood (and forgave) his dark side, Boston teammate Bobby Doerr. With this excerpt from his new book, The Teammates, the author explores a glorious friendship in two sports.

May 2003 David HalberstamWhat the other three remembered about seeing Ted Williams for the first time was that he was so tall and skinny, and looked so goofy. The idea of him as a pro ballplayer, let alone the great pro ballplayer and the great power hitter he would one day become, seemed most unlikely. No one that skinny could be a ballplayer, they all thought. "Six foot three and 147 pounds, the skinniest thing I ever saw," his friend and teammate Bobby Doerr remembered. Dominic DiMaggio, another teammate of Williams's, recalled his first glimpse much the same way: "Like a broom holding a bat."

Doerr remembered his first look at Ted. It was June 1936, and the original Hollywood Stars had just moved to San Diego and been reborn as the Padres, after Bill Lane, the owner, balked at a 100 percent rent increase for Wrigley Field, the ballpark the Stars and the Los Angeles Angels shared. Some San Diego politicians induced Lane to move the team south to what then was a city of less than 200,000 people. It was right before a game, just as the regulars were taking batting practice, when Williams, who had been playing for a local school, Herbert Hoover High, was brought in for a tryout. "I was standing right near the batting cage," Doerr remembered, "on the first-base side—I don't know why I was there, but I remember the scene distinctly. And here is this kid, and he is really skinny. You wanted to laugh—no one that thin could possibly hit. 'Let the kid hit,' Frank Shellenback [the team manager] is saying, because he's been told that by Bill Lane, who wants to look at Ted. The veterans are all grumbling—you know, we all wanted our batting-practice swings. No one thinks he can be a ballplayer, he's much too thin, and we've got a game in an hour or two, and he's not even going to play with us. So we're impatient, and there's a lot of resentment, a lot of muttering. And then he started to swing. And we all remembered that swing. You paid attention to the swing. He hit six or seven balls very hard, and all the veterans are starting to watch, and it's getting very quiet, and I remember one veteran player saying, 'That kid is going to be signed before the week is out.'"

They had, the four of them—Ted Williams, Dom DiMaggio, Bobby Doerr, and Johnny Pesky—played together on the Red Sox teams of the 1940s; Williams and Doerr went back even further: they had been teenagers together on the San Diego Padres of the old Pacific Coast minor league and played with Boston in the late 30s. All four were men of a certain generation, born right at the end of World War I within 31 months of one another—DiMaggio in 1917, Doerr and Williams in 1918, and Pesky in 1919. Doerr's middle name, in fact, was Pershing, after John "Black Jack" Pershing, the general who had led the American troops in Europe in the Great War.

They were all special men—smart, purposeful, hardworking—and they had seized on baseball as their one chance to get ahead in America. They had done exceptionally well in their chosen field. Williams and Doerr were in the Hall of Fame. Many of the players from that era were puzzled that DiMaggio and Pesky had not been eventually inducted by the old-timers' committee, which took a belated second look at who had made the Hall and who had not. That was particularly true in the case of Dominic DiMaggio, who had been an all-star seven times; Williams himself believed it was a travesty that Dominic was not in the Hall. None of the four, most assuredly, had gotten rich off the game, not in the era they played in and not in the material sense, for the richness they had taken from it was more subtle and complicated. A couple years ago, Pesky and DiMaggio were together at the funeral of Elizabeth "Lib" Dooley, a beloved Red Sox rooter who was considered the team's foremost fan, having attended nearly every home game from 1944 to 1999, and John casually asked Dominic how much he had made in his best year. Forty thousand, Dominic answered, and then he asked John the same question. Twenty-two five, Pesky said.

They had, after all, grown up in a much poorer America, when career expectations were considerably lower, when the people who went off to college were generally the people whose parents had gone off to college before them. Two of the four, DiMaggio and Pesky, were the children of immigrants. In DiMaggio's home, Italian was still spoken, and Pesky's real family name was Paveskovich, as his Croatian parents were still known, at least to themselves if not to the larger world. Williams had grown up in what was ostensibly a traditional Scotch-Irish home—what name could be more American than Williams?—but in fact his mother, unbeknownst to most of Ted's friends, was half Mexican.

For their entire careers they were basically one-city, one-organization men. Only Pesky played for any team other than Boston, when, at the tail end of his career, he was briefly with Detroit and then Washington, but the others felt those years and those at-bats did not really count. "We were all lucky to play professional ball, and, even more important, to play in Boston, which was such a great baseball town and a good organization. We were like kids in the candy store," Pesky recalled. "We felt very lucky to be in Boston," Doerr agreed.

That was something unusual in baseball: four men who played for one team, who became good friends, and who remained friends for more than 60 years. Their lives were forever linked through a thousand box scores, through long hours of traveling on trains together, through shared moments of triumph, and, even more in the case of the Red Sox, through shared moments of disappointment. They were aware that they had been unusually lucky, not just in the successful quality of their careers but also in the richness of the friendships they had made. And they were all too aware that it was unlikely to happen again, that the vast changes in the sport, especially free agency, made rosters more volatile, while the huge salaries somehow served to lessen the connection among teammates rather than solidify it. They and others who followed the sport realized there was less continuity and community on teams. Of the Red Sox teams of the 70s it was said that, when the team plane landed, the players quickly dispersed on their own—"25 players, 25 cabs."

Ted was the most compelling personality among them, not just the best ballplayer—perhaps the greatest hitter of all time—but the most dominating personality as well, both generous and combative in the same instant, ever tempestuous, the man-child who dominated every conversation, who shouted others down, who never lost a single argument to anyone. Joe DiMaggio, Dorn's older brother, might have hit in 56 consecutive games, a seemingly unrivaled record, but he never won 33,277 arguments in a row, like Ted Williams, the undisputed champion of contentiousness. Ted Williams never lost an argument, in no small part because he was bright and he marshaled his facts and argued well, but also because he shouted all the time and appointed himself judge and jury at the end of each argument to decide who won. He never lost an argument because he was Ted Williams. In his playing days, he would be there every day in the clubhouse, holding forth—the Ted Williams Lecture Series—at least a speech per day, orating and arguing at the same time. "I can," John Pesky said 60 years after he heard the basic lecture for the first time, "still hear him telling us, because he said it again and again, 'You'll get one good pitch to hit. One good pitch. That's all. Don't count on more. So you better know the strike zone. And when you get that one good pitch you better hit it and hit it hard. Remember, just one good pitch.'"

Joe DiMaggio hit in 56 consecutive games, but he never won 33,277 arguments in a row, like Ted Williams, the champion of contentiousness.

For many years, the glue that held them together as friends was Williams; someone that great, one of the very best ever at what they all did, had rare peer power. "It was," Pesky once said of him, "like there was a star on top of his head, pulling everyone toward him like a beacon, and letting everyone around him know that he was different and that he was special in some marvelous way and that we were that much more special because we had played with him."

He might not, the other three teammates knew, be the easiest man in the world to deal with. He always did what he wanted and never did anything he did not. But to no small degree they stayed close because he willed them to stay close. In a way, they had become his family—his real family, the one from his childhood, had been difficult, always causing him more pain than pleasure—and there was an awareness that Ted was always there for them. (This was true as well for some of Ted's other teammates, who were far less successful financially than Pesky, Doerr, and DiMaggio and who badly needed Ted's help later in life. If a former teammate was living near the poverty line, Ted would somehow find out and quietly make sure that he had enough money.)

When they were playing, Ted had been closest to Bobby Doerr. Bobby was five months older, but infinitely more mature, with an uncommon emotional equilibrium that would stay with him throughout his life. He never seemed to get angry or to get down. This stood in sharp contrast to Williams's almost uncontrollable volatility and meteoric mood swings. It was as if Ted had somehow understood the difference, that Bobby was balanced as he was not and that Bobby could handle things that he could not. Ted somehow understood that he needed Bobby's calm, and he seized on his friend's maturity and took comfort in it from the start.

"It was," Pesky said, 'like there was a star on top of Teds head, pulling everyone toward him like a beacon, letting everyone know he was different."

A home video exists featuring Williams and Doerr, the two of them arguing about hitting in the middle of a fishing trip on the Rogue River in southwestern Oregon in 1987. It captures a wonderful moment, one of many chapters in the 60-year debate between Williams and Doerr over hitting. Whenever the subject arose, Doerr became, in Ted's words, "that goddamn Bobby Doerr," as in "I can't teach that goddamn Bobby Doerr anything about hitting. I don't know what's wrong with him. He just won't listen." The marathon debate had begun when they were young; even then Ted was the most passionate of hitters, and hitting was nothing less than a science for him. No one studied it as diligently as he did, and he never put comparable energy into, say, the science of fielding. Ted was in a class apart in the way he constantly scrutinized pitchers ("dumb by breed") and what they threw and when they threw it. In the precomputerized age, everything was categorized and everything was stored away. As such, he was rarely surprised by what pitchers threw; if anyone was surprised, it was likely to be the pitcher. Ted was immensely frustrated by the fact that Bobby, a very good natural hitter, was not as passionate about the subject as he was.

There were all too many games when Ted would ask Bobby what kind of pitch he had just hit, and Bobby would say that he did not know, he had just gone up there and hit the ball. Ted would say, Goddamn it! How could Bobby Doerr not goddamn know what he had swung at? And then Bobby would try to explain the difference between being a middle infielder, where you were in on every play or at least had to be ready to be in on every play, and being an outfielder, where the pressures were far less intense. Being a middle infielder drained you. Well, an answer like that was pure bullshit, in the loudly expressed opinion of Theodore Samuel Williams, but if Bobby Doerr wanted to go through life being a goddamn .280 hitter, instead of a .300 hitter, he had Ted Williams's permission to do it. (Actually, Doerr turned out to be a career .288 hitter.) All of their teammates knew of the debate, had witnessed it countless times, and could years later quote back Ted's side, if not Bobby's, which had often been drowned out.

What none of them knew, or at least knew at the time, was that Bobby Doerr was one of the few people who could correct Ted when he slipped out of sync with his own swing. Periodically, Doerr noticed, Ted would go on a bit of a long-ball binge, hungering for home runs instead of just going up there and swinging naturally. When that happened, he tended to drop his hands just before he started his swing, but he did not bring them back up as he normally would, and it would throw the swing off. If anyone else tried to talk to Ted about his swing, he would explode, but Bobby could, though he had to do it in private. It all had to be done very deftly, phrased carefully, a loving suggestion, never a criticism. Even so, the fact that Ted would listen to Bobby reflected the unique trust he had in him. Doerr was, in fact, very astute about Williams as a hitter. For instance, in 1941, the year Ted hit .406, Bobby noticed that he had made a slight adaptation in his swing because he had chipped a bone in his right ankle during spring training. Every day Williams would have the ankle wrapped, and he favored it throughout the season. Because of that, Bobby believed, Williams as a left-handed hitter was favoring his right, or front, foot and staying back a little more when he swung and so he hit an inordinate number of sinking line drives just past the secondbaseman into right field.

"I can't teach that goddamn Bobby Doerr anything about hitting," said Williams. "I don't know what's wrong with him. He just won't listen."

At the crux of their ongoing debate, even more than Ted's feeling that Bobby should be more passionate, was the fact that Ted believed, actually he knew, you should always swing slightly up, as in: Well, of course, you should swing slightly up because the goddamn pitcher's mound, as everyone who knows anything at all about baseball except for Bobby Doerr knows, is 15 inches higher than the plate. (It was lowered to 10 inches after the 1968 season, when pitchers appeared to be overpowering hitters and the M.V.P.'s in both leagues, Bob Gibson and Denny McLain, were pitchers.) What was even worse, even more trying, was that he, Ted Williams—the last man to hit .400 in a season, as he and everyone else knew, and therefore he did not have to mention the fact—had been trying to explain this simple fact to Bobby Doerr for all those years and Doerr still did not listen, still insisted on that stupid, level swing of his. All that Doerr would do was answer that his swing worked for him. Which was obviously a terrible and inadequate answer. Well, then, maybe someone else could do something about Bobby Doerr, because he, Ted Williams, was going to wash his hands of Bobby and that sorry flat swing.

But Ted could never quite bring himself to let the matter drop, as the video proved. Ted had called Bobby that year and asked how the steelhead fishing was out in Illahe, Oregon, where the Doerrs had a rustic home. Bobby said it was good, or at least it was with the smaller steelheads. He invited Ted to come out and see for himself. Steelheads, it should be noted, are anadromous rainbow trout, fierce game fish that are bom and spawn in freshwater, but live in saltwater. They are more like salmon than trout, and are much prized by serious fishermen. Ted was interested in going after the big steelheads; Bobby said that might be more problematic, but that they would give it a shot and go out on the Rogue River, considered a great river for steelheads. Ted, in time, showed up, his three marriages by then over, and he was with a wonderful lady named Lou Kaufman, a kind and forgiving person with whom he had lived since the mid-70s. She was much admired by most of Ted's old friends and was, by consensus among them, the woman in Ted's life who seemed to understand him best and who could calm him down most readily when one of those instant moments of pure anger had been triggered. She was thoughtful and truly loving—and she seemed, I once thought, when we were all three together for a day back in 1988, as much parent to him as lady friend.

On this trip Ted was, Bobby thought, quite hyper—really revved up—and, as sometimes happened when he was in such a state, he was particularly hard on Lou. Practiced at how to handle this situation, she deflected much of his anger, pretending as if it were not really there. By contrast, Ted was respectful to Monica Doerr, as always, in part because she was Bobby's wife, and in part because she never bought into his baseball fame and whatever right it bestowed on him to be temperamental. She did not treat him as the Great Ted Williams, but just as she would any other friend of Bobby's.

Bobby thought Ted was edgy because several of Bobby's buddies were coming down to fish with them, and Ted was anxious about meeting them, wondering if it would work out all right with these strangers—like a little boy uncertain how he would do with new acquaintances. But then he met them and decided they were O.K., and he began to relax. He was loud and voluble nonetheless, and on their second day on the Rogue he started nicking away at Bobby on the subject of hitting. "You always chopped at the ball," he said. "No, I didn't chop," Doerr countered. "I never understood why you chopped at the ball so much," Ted answered, thus turning the disputed point into a fact. As the argument continued into the third day, they decided to have a hitting clinic, right there on the banks of the Rogue. When they took their morning break, Williams and Doerr, in their grubby fishing clothes, agreed to present their respective arguments. Fortunately for posterity, one of Doerr's friends had a video camera. The other men gathered around, and ground rules were set: five minutes for each man to make his case. First, Ted gave his view of hitting, that the pitcher's mound was up, and so you had to swing slightly up, 12 percent to be exact. (If this was true, Bobby had sometimes teased him, what about curveballs, which broke down? Should they be hit with a 45-degree upswing?) Then it was Bobby's turn: he believed too many hitters swung over the ball precisely because they were swinging up. Patiently and modestly, he laid out his case, while, in the background, Ted tried to distract him, arguing, haranguing, doing everything he could to break Bobby's concentration.

"Watch out when you fish with Ted," Billy Goodman, a former teammate, warned Doerr. "You wont even be able to get in the boat the right way.''

Anyone watching the video had to wonder what it must have been like for other fishermen on the Rogue that day, floating down the river in search of steelheads and coming upon this boisterous party on the bank, and hearing an overpowering voice echoing up and down the river, and looking up to see a tall, older man wearing baggy old clothes, shouting to everyone and then taking practice baseball swings. Any other fisherman witnessing this must have been utterly puzzled by the scene-batting practice on the Rogue River during steelhead season?—and then realized, even as his boat swept by and went a little farther down the river, what it was all about and that that large, rather voluble man was Ted Williams—yes, Ted Williams—holding a riverbank hitting clinic.

Fishing, as much as baseball, had always brought Williams and Doerr together. A couple of neighbors—in particular, a man named Les Cassie, whose own sons weren't much interested in fishing—had taken Williams fishing as a boy, and he had loved it from the first, the solitude of it, the way it enabled him to escape from other pressures at least temporarily, and, perhaps most important for Williams, the chance it offered to seek perfection and to excel in yet another arena. Bobby Doerr had also been pulled toward the outdoors since boyhood, and when he had played with the Padres, Les Cook, the team trainer, kept photos of the Rogue posted on his notice board. Cook fished the river in the off-season and often talked with Doerr about how beautiful the river was, and how good the steelhead fishing was there. So when Bobby was 18 years old, still a minorleaguer, he went there with Cook, and he knew from the first day he saw it that he had found an outdoorsman's paradise. In time, borrowing a little money from his father, he bought 160 acres there, and for the next 60 years he never emotionally left the area.

Bobby Doerr loved Ted Williams. Knew all of his faults and loved him just the same. It was a rare thing to go back that far with anyone, let alone a teammate, and to share so much history with him, Doerr believed. As two young, new players on the Padres they had bonded first because they both liked going to movie Westerns, especially ones starring Gene Autry or Hoot Gibson. Doerr soon became Ted's confidant, the one person he could always turn to. Later, when they were both on the Red Sox, and Williams struggled to deal with fans and the media, and on occasion with some of his older teammates, he and Doerr would often arrive in a city by train and check into the hotel together. Williams, restless and edgy—always high-strung from the pressures that went with being a superstar, from the additional pressures to excel that he put on himself, and, Doerr guessed, from the nature of his emotional wiring—would want to go for a walk, but only with Doerr. If another player wanted to join them, Ted would, more often than not, simply go back to his room. Being close to Ted in those years had given Doerr a special sense of the pressures that are suffered by a star on a great team.

It was a cherished friendship for both of them. But that did not mean it was ever easy. There were going to be wonderful days with Ted, and there were going to be stormy days as well—tempestuous was the word that Bobby used for his friend. There were going to be things Ted did that you simply could not explain to other people, who would find the changes in his behavior inexplicable. Sometimes for no apparent reason he would simply explode at you, and it made no difference what you did or said; if you were there when one of those moods hit, then it was simply your bad luck.

That extended to fishing with him, whether in Oregon or back in the Florida Keys during the 30-odd years that Ted had a place there. Part of it was that he was always both a perfectionist and a purist, as much in his fishing incarnation as in his baseball one. Everyone knew that, including Carl Yastrzemski, the talented ballplayer who had replaced Ted in left field for Boston in 1961, two men playing one position for one team from 1939 to 1983 (minus Ted's years in the service). Back when Yaz was playing, Ted still went to spring training as a hitting instructor. Hearing that Yaz liked to fish, Ted invited him to go fishing. At the appointed hour, Yaz showed up at the dock where Ted kept his boat, albeit carrying a cooler. "What's in the cooler?" Ted asked. "Some beer," Yaz answered. "There's no beer drinking allowed on my boat," Ted said. "O.K.—see you, Ted," said Yaz, who turned away and went home. Ted's old teammate Billy Goodman, who for a time had lived near Ted in Florida, used to warn Doerr about fishing with Ted. "Bobby, watch out when you fish with him. You won't even be able to get in the boat the right way—you're sure to do something wrong." (In fact, to Billy Goodman's eternal shame, he had done something quite egregious: on a very hot day in the Keys when Ted was supplying everything else—boat, rods, lures, and lunch, usually an apple—and Billy's one responsibility was to bring a thermos of ice-cold water, he had forgotten the water. That, given the brutal heat in the Keys, was not a misdemeanor; it was perilously close to a felony.)

"We all remembered that swing," Doerr recalled of batting practice in1936. "One veteran player said, 'That kid will be signed before the week is out.' "

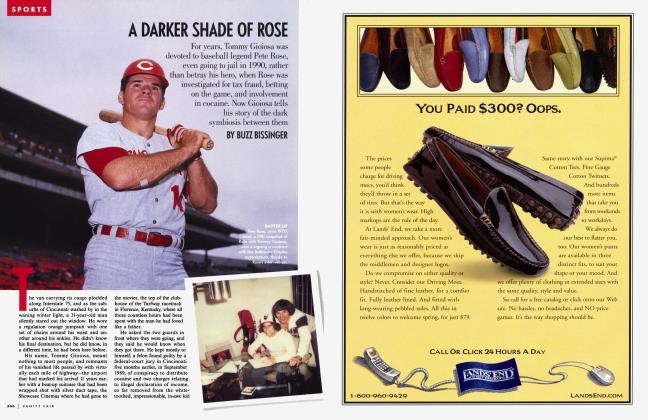

One of the worst days of Bobby Doerr's life had been spent fishing with Ted in the Keys. It was in Islamorada in 1961 or '62, before the developers had found and overbuilt the area; it was still one of the great light-tackle fishing venues in America, especially good for tarpon and bonefish. Bobby had been scouting for the Red Sox, looking at a catcher named Carl Taylor, who lived in Key West. Taylor was the half-brother of Boog Powell, the big, powerful first-baseman of the Baltimore Orioles, and the price on Taylor was going to be around $50,000, a lot of money in those days. So the scouting process was serious business. Bobby was going to be in the Keys for a few days, and Ted invited him to come by and do a little fishing. The tarpon fishing, Ted told him, was very good just then.

Here it should be noted that Bobby Doerr is a first-rate fisherman, a man who takes the sport with appropriate seriousness. Any man who built one of his two homes in the most remote part of Oregon because of the steelhead fishing and who went there regularly before there was even a road into the area is someone who has obviously made fishing a singular priority. By Doerr's own estimate, and he is an uncommonly modest man, he was not as good a fly-fisherman as Ted—almost no one he ever knew was. "Ted was so big and powerful that he could always put the fly 20 feet farther on a cast than I could," Doerr recalled. But Doerr could obviously handle a fly rod with exceptional skill, and the best evidence of this was that Ted always looked forward to fishing with him.

On this day, they arose in Ted's very comfortable home in Islamorada (spotless, everything perfectly cared for, and everything put away, as if to stand in direct contrast to the grim, messy home he had grown up in), and Ted said that he would do the eggs if Bobby would do the grapefruit, and, almost as an omen of what was to come that day, Bobby had cut the grapefruit improperly. There, in the home of one of the last great perfectionists in America, he made one great circular sweep with the special grapefruit knife, thus separating the fruit from the rind, but he stopped there, and, regrettably, he did not cut the grapefruit into little sections! Ted didn't explode at Bobby, but he did say something sharp about it, and there was no doubt that Bobby had transgressed, that he had failed the grapefruit-cutting test, the first but by no means the last test of the morning. Then they went to the dock for the boat that Ted used—a small, flat boat, about 14 or 15 feet long, with as little draw as possible, because so much of the fishing in the Keys is sight fishing and you have to pole the boat in very shallow water. Bobby had had to borrow a pair of tennis shoes for the day, and he tracked some dirt onto the boat as they got in. Ted shouted at him, Goddamn it, why can't you wash your shoes down? It was not a good sign. Billy Goodman, it turned out, had been a prophet.

To go after tarpon, they were using a new casting reel that Ted had been working on for Sears—he had been hired as a fishing expert and adviser for the company. As soon as they got out into the water there were very big tarpon all around them, rolling on the surface, some of them, it seemed, well over 100 pounds. Ted was poling the boat, and Bobby was fishing, standing on the seat, on top of a tackle box, which they were using for extra height in order to spot the fish better.

Earlier, before they went out, Ted had been pushing to use spinning reels, which were more modern and less likely to have snarls, but Bobby, somewhat of a traditionalist, suggested the new casting reel, it being a more modem version of the kind of reel used before spinning reels were invented. They soon spotted a very big fish, and Bobby cast out to it, and as he did he sensed that the line in his reel was for some reason too loose, even though he had checked it earlier. Line too loose in a reel was a genuine problem because it could easily snarl, creating a complicated knot inside the reel, thus stopping the line from feeding out when a big fish began its run. Bobby tried to tighten the line, thought he had succeeded, and now made a perfect cast. The Fish, a big tarpon, at least 80 pounds, maybe more, hit the lure and jumped twice and then went down deep, part of its run, but there was a backlash in the reel, the line quickly knotted, and the fish broke off. Ted simply exploded—at Bobby, the line, the reel, and the fish.

Bobby, something of an expert on Ted's language, had never heard anything like it before. There was an explanation, of course: here was the perfect day, the perfect fish, and Ted was being the perfect host, not fishing himself but putting his best friend on to a giant fish; everything had been perfect, and yet failure had resulted. Ted hated failure—for complicated reasons it was more threatening to him than it was to most men. Days like this—fish that big and eager to hit so readily on the first cast—did not come that often; it was far too easy for something to go wrong. Thus, in his anger, he began shouting that Bobby with his goddamn reel had really screwed up. This was a violation of the cardinal rule of fishing: when two men are fishing together and one of them breaks off on a big fish, the presumption is that the man who loses the fish feels bad enough as it is, and does not need to be taken to the woodshed.

They did not see any more groups of tarpon rolling like that, but they did spot individual tarpon, lying on top of the water motionless, looking at a distance like giant logs. Soon they moved in on another fish, but the angle was bad, and Bobby cast poorly, missing the chance to lead the fish properly, and spooking it in the process. The tarpon raced off into other waters. This provoked more X-rated language from Ted, and Bobby had a sense by then that, surrounded by giant fish or not, this day was going to be a first-rate disaster, one that he would long regret.

Just then they spotted another huge tarpon lying in the water, but the problem with this fish was that, given the angle of the sun, it was impossible to tell which end was the head and which the tail, a critical factor if you are trying to cast just above the head. So Bobby cast, and this cast, unlike the previous one, was perfect, except for one thing: he had cast to the tail, which spooked the fish. At this point Ted was apoplectic. A brief, heavily expurgated summation of his tirade was that Bobby goddamn Doerr did not know a goddamn thing about fishing, that he had taken shots at three goddamn giant fish—goddamn trophy fish—and screwed each one up, spooking two and breaking one off, though a child could have caught all three.

At that point Bobby's back began to hurt—he had a chronic bad back, which had ended his baseball career earlier than he had wanted. Standing on the tackle box seemed to be making it worse, so he stepped down, fervently hoping that they would not see another tarpon for the rest of the day. But then Ted started shouting for him to get the hell back up there, because there were going to be more goddamn fish. And regrettably there were. For right at that moment, they spotted the biggest tarpon of the morning. Perhaps 150 pounds. Just lying out there. Bobby's fatigue and dismay were replaced by the eternal optimism of all fishermen, that the last cast of the day will bring the biggest fish.

Bobby made a perfect cast, thanking the gods for that. As the lure moved near the tarpon's mouth, Ted said, "Give it a twitch," and Bobby did. The fish seemed to be eyeing the lure more closely. "Give it another twitch," Ted said, and Bobby did. The fish hit the lure hard and took off. Then it jumped, majestic, bigger than they had thought, and took off again. And then the line broke. Bobby was sure that he had done everything right, that the drag was set correctly on the reel so that the line was not too tight, and that he had handled the fish perfectly in their brief but exciting encounter, with a solid but nuanced tension point on the line. But the line had snapped anyway. What had happened, he decided later, was that the backlash on the first cast of the day had somehow weakened the line somewhere and created a stress point, causing it to snap later. Whatever happened, it occasioned the worst verbal assault on him yet.

It was an awful day. One of those days that stand out in a long and wonderful friendship for all the wrong reasons. Here they were, trying to do something that was supposed to give them both pleasure, but everything had gone wrong, and it had put their relationship to an acid test. Had Bobby Doerr been anyone else, someone not as balanced, someone not as comfortable with himself, someone who didn't understand Ted so well, it might have ended the friendship.

But Bobby understood the complete context. That was Ted. They had been friends for some 25 years, and Ted loved him. What you had to do at moments like this was simply get through it and put it behind you.

What he also understood was that the person Ted was hardest on, excepting perhaps his wives and children, was himself. Up until then Bobby had thought there were two Ted Williamses: a sunny, joyous, generous one who could not wait for another day of life, especially if it involved a game of baseball or a fishing expedition; then there was the impatient and explosive Ted, unable to control his moods, as grown men were supposed to. For the first time, Doerr decided there might be even a third Ted Williams, someone even darker and more volatile, with even less self-control. They went to the house, and that night Ted said, "I guess I was a little tough on you out there today." That, Bobby thought, was as close to an apology as one was ever going to get from Ted Williams.

"What's in the cooler?" Ted asked Carl Yastrzemski. "Some beer" Yaz answered. "There's no drinking allowed on my boat," Ted said.

Perhaps I should note here that I had a sixth sense about scenes like this taking place on the water, and though I am a very serious fisherman and get great pleasure from my time on the water, I had concealed the fact that I am a fisherman from Ted Williams when we met for the first time, in 1988. There was a reason for this: I am skilled with old-fashioned casting reels and with spinning rigs, the chosen tackle for light saltwater fishing (bluefish and striped bass) off Nantucket, where I have a summer home. But I am not good with a fly rod, which surely would have been Ted's preferred instrument, especially if we had gone for bonefish, which I had pursued on earlier trips to Islamorada without much success. Flyfishing demands a far greater level of skill than spin casting. I came to it relatively late in life, and I do not get much chance to practice. I grade myself a C+ practitioner, although occasionally I fish for a week or so and get myself up to B-, but then inevitably I slip back.

I was interviewing Ted for my book about the 1949 pennant race between the Yankees and the Red Sox, Summer of '49, and I knew if I told Ted I fished he would insist we go fishing first (his terrain and area of expertise) and do the interview second (my terrain and area of expertise). Somehow I envisioned pure disaster ahead. Though I did not yet know the story of Bobby Doerr and the giant tarpon, I could imagine one just like it, with me fishing like a donkey. Then Ted would no longer take me seriously as a reporter and historian. My grade as writer would be the same C+ I got as a fly-fisherman, or perhaps it would be even worse, for I might unravel under the pressure of his cold and unsparing eye. Perhaps the interview would be canceled entirely. It was all too great a risk to take. And so I was secretive about it and waited until the very end of our long day together, and then, as we were parting, I slyly mentioned that I was a fisherman. Well, goddamn, why hadn't I told him? he exploded. We could have spent the day fishing, and done the interview the following day. Yes, I said, it was a shame we had not gotten our priorities right, but maybe next time ...

My day with him had been magical. Because Ted Williams had remained properly wary of all reporters, the people he called "the Knights of the Keyboard," the visit had been midwifed by our mutual friend, Bobby Knight, then the basketball coach at Indiana. (I was probably Knight's most unlikely friend, as he was mine, but he had a fascination with the military and with Vietnam, and I had one with college basketball.) The fact that Bobby had vouched for me got me over the moat, and so it was that one morning I was ready at eight at an Islamorada motel, as ordered, when Ted came by, exactly on time, banged on the door, took one look at me, and shouted, "Well, you look just like your goddamn picture—let's go."

Ted was a big kid who had never aged.... I was alternately dazzled and then almost exhausted by his energy and his gift for life.

I got the first Ted Williams, as Bobby Doerr would see it. What I remember most clearly was the joyousness and the zest for life. There was a great deal of talk about hitting, much of it about his failure to get that goddamn Bobby Doerr to swing slightly up. For a brief time, Ted even worked on my swing—he was kind enough to say that he saw some promise in it. I am six feet three, and I swing lefty, but I think that pretty much took care of any similarities between Ted and me. Ted also, I should point out, wanted to talk politics, and he was considerably more conservative and more hawkish than I. (He seemed to have far greater belief in the effectiveness of airpower used in underdeveloped countries than I did.) And since in those days the great issue of American foreign policy was the degree of intervention in places like El Salvador and Nicaragua, he wanted to argue, which he did, in favor of going there and wiping out anyone who was in our way, and he brushed aside my arguments that neither of these countries posed very much of a threat to the security of the United States of America. I am sure that he won these arguments, because he had, after all, never lost one before.

I have spent no small amount of time in retrospect trying to figure out why it was so glorious a day. Part of it was the matchup—here I was at 54 dealing with a great figure of my childhood, in a scenario that allowed, indeed encouraged, us both to be young again, me to be 12 and him to be 28; part of it was a sense that he was special as a man and that he was, like it or not, a genuine part of American history (something I suspect that he had come to believe in some visceral way himself, but did not know exactly how to articulate); part of it was that he had lived his life in an uncommonly independent way, according to his own norms and beliefs and not those of others; part of it was the fact that at 70 he was still one of the best-looking men in America; but most of it, I decided later, was that he gave so much. It was the unique quality of the energy level—I have rarely seen it matched. He gave more than he took. In the age of cool, he was the least cool of heroes. Rather, he was a big kid who had never aged and had no intention of aging; I was alternately dazzled and then almost exhausted by his energy and his gift for life.

I have this view of him now, and it was beginning to form back then, that it had all come around to him because he was not a modem man, had always gone his own way, always outside the bounds of contemporary society, and had been so absolutely true to himself. He did not wear ties to tiecertified events. He had crash-landed his plane in Korea once because he thought that there was a better chance to preserve his body that way than if he parachuted out, which might have been harder on his legs. It was a bet, and he had won. He always, if you think about it, bet on himself. He did not go around doing things that would make him popular; instead, even when there were things about him that were appealing, he tended to keep them to himself. He was always his own man.

I think in that sense the .406 is special and defining, not in that he was the last man to accomplish it, but, much more important, because of the way he did it. On the last day of the season, Boston faced the Philadelphia Athletics in a doubleheader; Ted's average rounded out to .400, and manager Joe Cronin had offered him the day off. But Ted Williams did not round things out, and he had played, getting six hits, and taken the average up to .406. Somehow that stands in contrast to so much in today's world, where there is so much hype and where too many athletes who are more than a little artificial have too many publicity representatives and agents, all of whom, it strikes me, would have told their client to sit it out, rather than risk losing millions in endorsements (and in all too many cases the client would have listened). Instead, he had just gone out and done it, long before the Nike people figured that slogan out, that they could make lots of money selling the idea of doing it to millions of Americans who did not just do it. There was an alabaster quality to the decision, and would have been, I think, even if he had gone hitless. The idea of Ted Williams choosing anything else seems inconceivable.

"I can hear him telling us," remembered Pesky, " 'You'll get one good pitch to hit. And when you get that one good pitcl you better hit it and hit it hard.' "

In August 1946, when I was 12, and the Red Sox were making their extraordinary run to the pennant, I had seen Ted play; it was a moment when they were all still young and seemingly immortal, and they had all returned from the war to find that their skills had not deserted them. That summer, my family was still living in Winsted, Connecticut, where we had lived during World War II, and my father was finally back from the war, and it was a big event for us, driving down to Yankee Stadium, in celebration of my brother's 14th birthday. Ted had hit two home runs that day, as had a Yankee catcher named Aaron Robinson, soon to be traded to the White Sox for Eddie Lopat. One of Ted's two home runs had been the hardest ball I have ever seen hit, both then and in the ensuing 56 years, an imperial shot into the third deck in right that seemed to be rising even as it smashed into the seats. And so we were sitting there, 42 years later in Islamorada, and I described that moment, and he looked at me and smiled broadly and said just two words, "Tiny Bonham," which was the name of the pitcher who had served up the ball. Later, it struck me that I had failed slightly as an interviewer by not asking what the count was and what kind of pitch Bonham had thrown. Surely he would have known the answer.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now