Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowA Man of Wars

CNN's Peter Arnett writes of arms, men, and the airwaves

There was from the start always a certain brashness to Peter Amett. It was in his voice, with his Kiwi accent, and in his walk, which had a slight swagger, and in his face, which was adorned with the broken nose of the ex-boxer and which made him H look some 31 years ago, when we first met, like a New Zealand Jean-Paul Belmondo. He backed down from nothing. I do not think he sought arguments over the veracity of what he and others of us filed, but those were heated days and there were always people, newly arrived in Saigon, who were eager to lecture us about what we were doing wrong, and about the cowardice of the other side (when it did not stand and fight), and, most of all, on our journalistic obligation to write stories which pleased American commanders. None of us took these lectures well, but I think he took them less well than the rest.

Now comes his first book, the one he meant to write years ago, Live from the Battlefield (Simon & Schuster), the exceptional testament of a magnificent reporter. He was 27 when he first showed up, and until then his had not been an entirely auspicious career. He was very much the hitchhiker on the outer fringes of Pacific and Asian journal-ism at the time, having started out on The Southland Times in Invercargill, New Zealand, for 30 shillings (roughly five dollars) a week. He went from there to The Standard, a weekly in Wellington, thence to the Australian Sydney Sun, and thence to the English-language Bangkok World (up now to $300 a month). While he was publishing The Vientiane World, his own English-language paper in Laos, the Associated Press hired him as a correspondent in Jakarta, whence he was expelled by Sukarno. Finally, in June 1962, he was sent to Saigon.

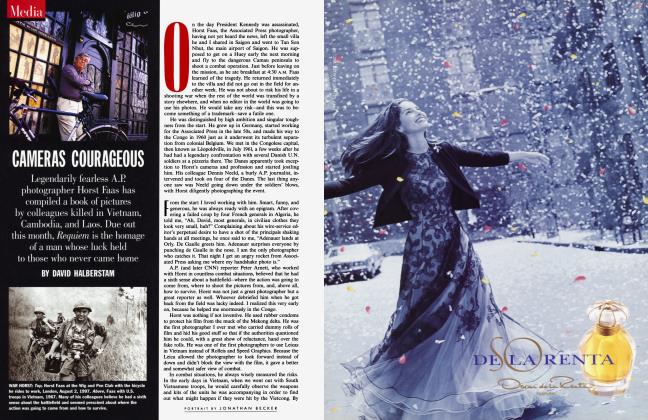

There, covering this most demanding assignment, Peter Amett bloomed. He left 13 years later, with the fall of Saigon, as the great reporter of the Vietnam War, the journalist most respected and beloved by his peers. No one saw more combat, and no one put himself more on the line, and no one evoked less jealousy than Amett, inevitably accompanied by his colleague Horst Faas, the brilliant A.P. photographer. They were inseparable, their names twined into something of a single brand name—they were known as Peter-and-Horst, or, alternately, Horst-and-Peter. The chief problem with covering the Vietnam War, my friend and colleague Charles Mohr of The New York Times once lamented, was that when you heard of a major battle you spent all day trying to find a plane or chopper to get there, then finally flew in under heavy fire only to discover that Peter-and-Horst had already been there, gotten the story, and left.

Peter won the Pulitzer in 1966, and he came close to winning it again two years later when the committee on international reporting recommended him for the second time, but the jury gave it to someone else for coverage of the Six-Day War. (Faas won it twice, first for Vietnam and then for his work in the India-Pakistan war.) How Amett found the inner strength to keep going year after year I do not know. Others on much shorter tours wore out, and some unraveled to varying degrees, but Amett seemed to get stronger. And he never - lost. He grew as a man as well, I thought, starting out as a kind of glorified police reporter covering the battlefield, then becoming a remarkable combat reporter, and gradually using Vietnam as a university for the larger lessons of human folly, emerging as a man of infinitely greater subtlety and sophistication. For all of that, few outside his profession knew his name, in large part because he worked for the A.P., and much of his best work went without a byline. Therefore it was only fitting that when he left the A.P. he went to CNN and in time surfaced as the one reporter in Baghdad at the start of the Persian Gulf War, becoming overnight the most famous and visible reporter in the world—the first great war reporter of McLuhan's now embattled global village.

DAVID HALBERSTAM

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now